Debt. A four letter word that can give you incredible insomnia if not managed well. Makes one think, how does the Minister of Finance in Pakistan’s government, or any government for that matter get any sleep? Do they wake up from nightmares with cold sweats? Or do they uneasily murmur out the words deficit, IMF, and default in their sleep? It is a heavy responsibility” one wrong step and you cost the country billions, maybe even trillions of rupees. Perhaps even worse, the possibility of getting a phone call from the National Accountability Bureau (NAB).

One such step that has often been criticised in economic circles, but also never fully understood, is the domestic debt reprofiling that the Ministry of Finance (MoF) undertook last year. Simply put, the government decided to issue new bonds to accomplish two goals: reduce the frequency with which they have to pay back government bonds (by extending the average maturity of the bonds), and to take advantage of falling interest rates and issued new bonds at lower interest rates to pay off older bonds, which had higher interest rates.

That seems straightforward enough, but it appears that the government may not have handled the process in a manner that would optimally reduce the amount of interest it has to pay on its debt, and has raised concerns about competence, or worse, favours to the banks, in the choices of transactions the government has made in conducting its reprofiling of its debt.

What did the Finance Ministry do?

The Ministry of Finance reprofiled the government’s existing SBP debt from short term (6 months) to medium to long term (1 to 10 years) on June 30, 2019 right before the end of the fiscal year.

About 70% of the debt was reprofiled into ten year floating rate PIBs. Floating rate PIBs are a new type of bond whereby the interest fluctuates with changes in the policy rate. As a result, as the policy rate came down, the interest payments for these bonds have too.

However, the remaining 30 percent was reprofiled into fixed rate PIBs with tenures between two and five years. Despite these being only 30% and negligible in comparison to the former, the government still went on to do this at a time when the policy rates were at an eight-year high. And the decision to reprofile debt into fixed interest rate bonds at that time is the subject of considerable controversy.

In simple terms, why did the government decide to reprofile debt when the benchmark interest rate was at a high of 13.25%?

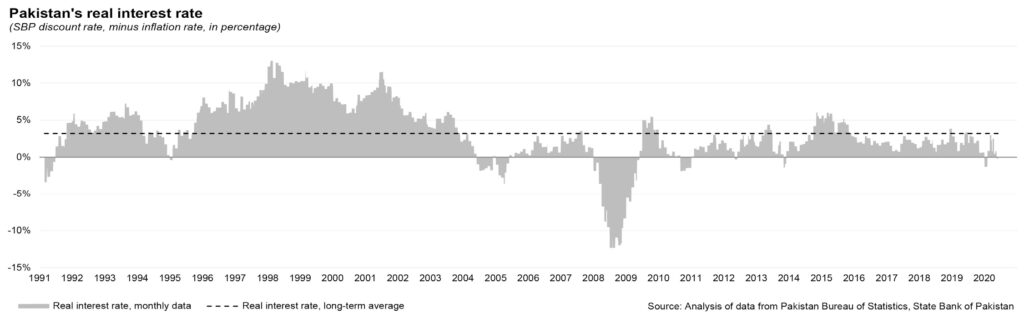

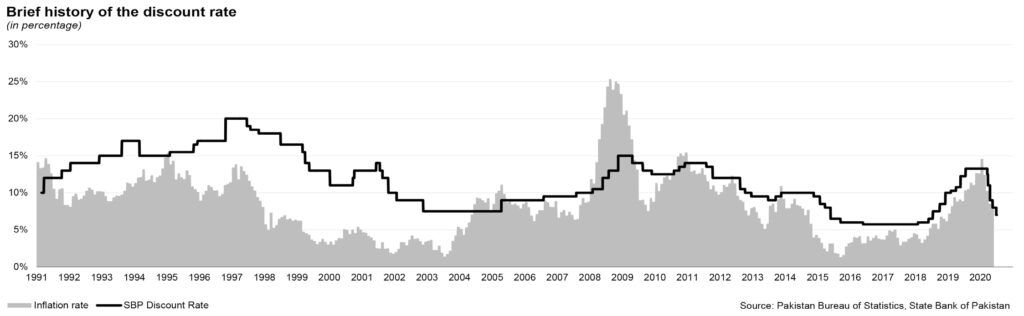

Consider the circumstances at the time of the transaction in June 2019. Inflation had risen rapidly, and as a result, the State Bank had raised interest rates by 325 basis points over the preceding six months in a bid to control that inflation. While the government cannot definitively predict the direction of inflation, there was ample evidence that economists – both inside and outside the government – believed that inflation would likely not go much higher, which meant that interest rates would also likely not rise much further.

The finance ministry cannot reasonably have known that interest rates were peaking in June 2019, but it could reasonably have inferred from both private sector and government economists that rates were unlikely to rise much further. So why choose to reprofile debt right after an aggressive cycle of rising interest rates? Why lock oneself into high rates?

Miftah Ismail, former finance minister, says that there is nothing wrong in reprofiling. “There is absolutely nothing wrong in going for long term debt. However, choosing to make this decision when policy rates are at 13.25%, however, is not the right time,” he says. “It makes very little sense.”

Indeed, the best time to reprofile the government’s debt would have been anytime between May 2016 and January 2018, a period of nearly 20 months when the benchmark interest rate was at 5.75%, the lowest it has been for the past 30 years for which Profit has been able to find data from the State Bank.

Then there is the fact that the debt being reprofiled is the amount the government owes to the State Bank, and not other borrowers. Government debt held by the State Bank is different from other types of debt.

The interest payments that are made by the finance ministry to the SBP make their way back to the government in the form of non-tax revenue when the State Bank makes a profit on those loans and then pays it back to the government in the form of a dividend. This basically means, the government is paying itself for a loan it gives itself – money from one hand into the other and back into the first.

This is the primary reason borrowing from your own central bank is seen as an inflationary move because it increases the money supply: it is, in a nutshell, the same as literally printing the money to pay for whatever it is the government wanted to buy with the debt it issued.

What impact does the reprofiling have on Pakistan’s debt?

Following reprofiling, the government was able to bring down its domestic debt maturing within one year to 37% of the total in June 2019, compared to 66% in June 2018. This was done to bring down the refinancing risk. Moreover, this helped prop up the average time to maturity of domestic debt to 4.2 years in June 2019, which had been as low as 1.6 years in June 2018. This is in line with the long term target set by the government for its domestic debt portfolio.

But first, an explanation of what these terms mean and why they matter. The government issues primarily two kinds of debt: Treasury bills (T-bills) and Pakistan Investment Bonds (PIBs). T-Bills are debt issued by the government with a tenure of one year or less. PIBs typically have a tenure of longer than one year, and are generally issued with maturities of three, five, 10, 15, and 20 years. Investors receive interest semiannually. They are coupon bearing instruments and issued in scripless form. This means that there is no physical form.

There are also some other terms to understand, such as the difference between permanent, floating, and unfunded debt.

Permanent debt includes medium and long-term debt such as treasury bonds, or investment bonds take longer to mature with tenors of 3, 5, 10, 15, and 20 years. They are sold through primary dealers at auctions, usually on a quarterly basis.

Primary dealers are banks or other financial institutions (in Pakistan, they are only banks) that are appointed by the SBP to participate in the government securities auctions. As a general principle, the longer the duration for the bond to mature, the higher the yield one would receive due to the risk associated with time. These are called Pakistan Investment Bonds or PIBs for short.

Floating debt is made up of short term borrowing in the form of treasury bills or T-bills, mature in a year or less, available in 3, 6, and 12 month. Investors get the full amount on maturity while these are often sold at a discount to their face value, and are zero coupon securities. The difference between the selling price, discount value, and the price at maturity is the interest earned on a treasury bill. They are sold through primary dealers in auctions on a fortnightly basis.

This is not to be confused with floating rate debt, which just means that the interest rate on that debt is not fixed. Floating rate debt can be of any tenure. Historically, the government of Pakistan does not issue long-term floating rate debt, but it has chosen to do so for this reprofiling exercise.

Unfunded debt is the outstanding balances of the various national savings schemes, primarily made up of various instruments available under these schemes.

Domestic debt reached a level of Rs20,732 billion at end of June 2019, after an uptick of Rs 4,315 billion during fiscal year 2019. Domestic debt registered an increase due to reliance on domestic sources for financing the fiscal deficit, a build up of cash buffers, and the difference between cash and the realised value of PIBs.

The government had primarily relied on short term debt from the SBP for this in the form of Market Related Treasury Bills (MRTBs). This debt helped them pay off and retire their maturing debt. The government kept picking up MRTBs until May 2019.

Pakistan’s permanent debt was recorded at Rs12,087 billion at the end of fiscal year 2019. Permanent debt has been declining in recent years, as banks were not willing to buy longer term debt owing to the inverted yield curve, which refers to the unusual situation when long-term interest rates are lower than short-term interest rates (generally, short-term rates tend to be lower than long-term rates).

“Commercial banks anticipated that the policy rate at 13.25% was bound to come down when inflation would recede. That is why they were willing to borrow at lower rates in the long term because they knew 13.25% was not sustainable,” said Hafeez Pasha, a prominent economist. “The market, especially banks are rational players.”

What did this exercise achieve?

One could argue that the inverted yield curve is a signal of confidence from the market that inflation is going to come down. The government would argue that this is a result of the right communication with the market where they have announced targets in advance.

For instance, in January 2020, following the reprofiling, the benchmark interest rate was 13.25%. One would expect that the coupon for the ten year bond would be auctioned at an upwards of the discount rate. However, banks bought ten year paper at 10.88%. This is a net saving of 2.67% on the Rs 20 million auctioned on January 9, 2020. This is just an example of net savings possible as a result of reprofiling.

However, given the fact that the net savings will also diminish the government’s dividends from the State Bank, it has relatively little by way of net impact on the government’s finances. Pasha calls the reprofiling an “accounting exercise”.

So, what did the government achieve from this exercise and if it makes no real difference why was it undertaken?

Well, the budget deficit and primary deficit are two distinct things. Primary deficit is when the government expenditure excluding debt servicing is more than total government revenue. “The government reprofiled to bring down the primary deficit because the IMF focuses on it,” said Pasha.

“It’s an accounting trick, it doesn’t impact the budget deficit.” This enabled the government to artificially bring down the primary deficit. As a result, Pakistan will be able to convey the message that it does not need to borrow to fully service its debt.

According to Pasha, Pakistan will soon be able to generate primary surpluses. This means that the IMF can then say that Pakistan has attained market maturity. “At the end of the day, what matters is what happened to your public debt, which is not limited to the primary deficit. What about the overall deficit?”

Sayem Zulfiqar Ali, a financial market specialist at the Asian Development Bank (ADB), explains: “the decision to reprofile has helped the government improve its maturity profile. Previously they were facing very large payments every two weeks. This has also helped improve cash flow.”

However, one advantage that has gone unnoticed is the pricing advantage that the government has been able to attain. “Every two weeks the government would have to roll over two trillion rupees of maturities and would have to raise an equivalent from commercial banks and entities,” he says. “That gave market pricing to banks and investors to charge more from the government.”

To put this in simple terms, say you were to get a loan of a hundred thousand rupees from a bank. A bank would likely charge you less interest and give you softer conditions than if you were to ask for a loan of ten million rupees. There are only 12 primary dealers that purchase bonds, as a result of the reprofiling, the government no longer needs to go into the market to raise large sums. The reprofiling resulted in a reduction of influence of these banks over government borrowing.

As a result of reprofiling, the government has set smaller targets. This has resulted in more competition within the market where market players compete with one another.

What about the private sector?

While Ismail said that the decision to reprofile should not be criticized unnecessarily, he said, “It makes more sense for the government to reprofile market debt instead.”

Reprofiling SBP debt is generally considered easier. After all, the SBP is a government institution, albeit autonomous. Convincing the private sector, however, is not easy. Similar to the G20 relief where private sector creditors have refused to provide relief to the emerging market players. While the government could supposedly leave banks no option but to reprofile their debt, that is against best practices.

“Reprofiling private sector debt, however, is not easy. Even if one investor backs out, the deal falls through,” explains Ali. “There are no firm guidelines therefore it is difficult to execute.”

While the government is not reprofiling its existing short term market debt it plans on doing in a different way. As the short term debt is maturing, the government is now issuing long term debt. It can be seen that last year the government set up a new strategy which can be observed by auctions.

In the case of new borrowing, less dependence is set on short term, whereas more on long term. Additional sums of money were not raised from T-bills, instead they were raised from PIBs. As a result, short term debt as a percentage of total debt went down through aggressive tactics by the MoF. However, despite that the stock of t bills went down in percentage form, but was not in absolute terms. Based on this year’s trend, one can assume that the it will also go down in absolute terms as t bill stock continues to reduce and new borrowing is done through PIBs.

Ali explains that the market in Pakistan which is primarily dominated by banks, does not set itself in the long term avidly. In order to overcome this, the government has introduced new long term floating rate instruments of different tenures for investors that do not want to take interest rate risk and in order to get rid of the confusion between floating PIBs that are part of permanent debt and floating debt, i.e. the short term, the ministry is also looking towards renaming these terms for clarity in communication.

What about government revenue from the SBP?

In simple terms, the government is not borrowing from the SBP due to the inflationary pressure it adds. However, it is obvious that as the government retires debt every year, the revenue obtained from the SBP will shrink and will eventually be reduced to nothing but the normal revenue that the SBP earns itself.

Sources in the government say that the decision to reprofile goes hand in hand with the decision to not borrow from the SBP. Not only is it the ideal functioning and considered a good practice around the world, but also helps private markets to develop.

Is the SBP free from government influence?

With the government deciding not to go for SBP borrowing, one could argue that this however is still done through the coy moves of the SBP. While the Finance Ministry feels that the SBP is free to inject liquidity whenever they feel the need. One could argue that the liquidity injected makes its way back to the government.

One quick look at commercial bank lending patterns shows how this money returns back to the government as banks and financial institutions continue to invest in government paper. While reprofiling was an interesting debate in economic circles, the real question one should be asking is about the crowding out.

That’s a good analysis. But more important than crowding is the increase in money supply. As rightly pointed out, as the SBP prints more money to finance fiscal deficits, a major problem that arises is that of inflation and debasement of currency.

One of the major reasons for the rampant CPI and asset inflation of the last decade could be attributed to the increased money supply. And not to forget the devaluation of the currency. As more rupees chase a depleting foreign currency reserve, the price of foreign currencies will undoubtedly rise. Basic demand and supply.

THis is a good article, however lets not get to hang up on debt if its to accumulate assets that add to national stock of tangible income-producing assets; trouble is it’s often used to finance consumption and day to day budgetary needs. Need to think of debt in terms of stock and flow, the national debt is the flow of historical annull deficits/borrowings, to which flow of yearly deficits are added. This is one reason Pakistan Debt to GDP ratio is high, can it be serviced, is there liquidiity and capaicty in the market to do so and at what cost. Without going into the maths the important issue is that the cost of debt in terms of the rate of interest or coupon needs to be below the rate of GDP growth. If its the other way around then the debt dyanamics could turn nasty; hence the focus on running a primary budget defitc and structural reprofiling of debt into longer term maturities to aid short term cash flow dynamics – all of which is short term fiscal tonic. The underlying dymanics and struture of pak economy remain weak: corruption; bureaucratic inefficiency; poor levels of tax collection; weak export base; huge losses at state run enterprises. The one statistic that highlights this is the high cost of debt servicing and how it crowds out state capacity to finance basic developmental needs.