Kulsum Nabeel remembers the moment well. The creative head of Sapphire was considering creating a women’s undergarments segment for the brand, and was busy conducting market research. She and the chief of merchandise (a man) had flown to Sri Lanka to view bras from different exporters. They had worked for years together, and Kulsum trusted his advice. As Kulsum had always done in various meetings, she passed on the products to him to ask for his opinion on the cloth colour, quality etc.

“As I kept passing bras to him, I didn’t seem to realise that he was getting redder and redder in the face, and was really just dying of embarrassment,” recalls Kulsum. In that moment, the ingrained societal taboo regarding bras really hit her.

The truth is that all of us, of all genders, have been some embarrassed version of that merchandise head at some point in our lives, because of the one golden rule in Pakistan: you do not talk about bras openly.

Shame – it is such an inextricable part of the socialisation of women in this country, particularly when it comes to anything related to women’s bodies – think periods, or pads, and yes, bras and underwear. One could write multiple essays on why that is so – and indeed several academics and activists have – but as a business magazine, Profit would like to focus on how this cultural shame affects how we talk about, market, sell and buy women’s undergarments in the country.

Considering that half of the 220 million people in Pakistan are women, it is astonishing that there barely exists any market research on Pakistani bras and panties. There is also negative interest shown by the textile industry to venture into the undergarments industry. The International Foundation and Garments (IFG) was set up in the 1970s by Triumph International, and to this day is still the main local supplier.

Yet while Pakistan’s industry remains stunted, at the same time, demand is rising. Pakistani women are earning more money, have more disposable income at hand, and have access to social media that helps them discern between low and high quality products.

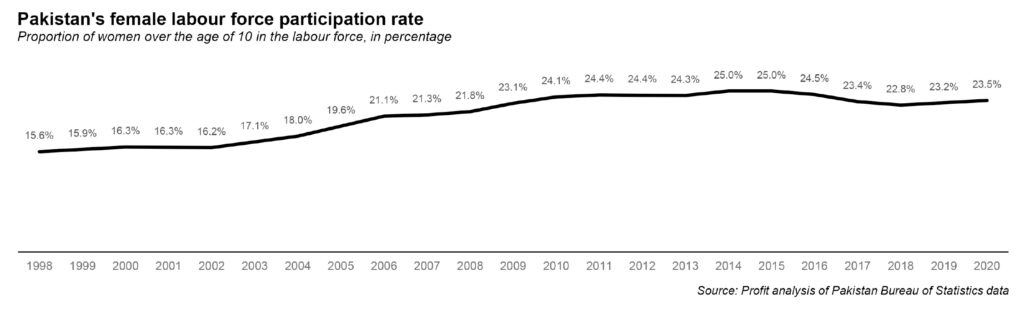

The data on Pakistani women’s rising economic power is staggering. The female labour force participation rate rose from under 16% in 1998 to a peak of 25% in 2015 before declining slightly once again to 22.8% by 2018. That means there are millions of women who are currently working who might not have been, had labour force participation rates for women stayed the same.

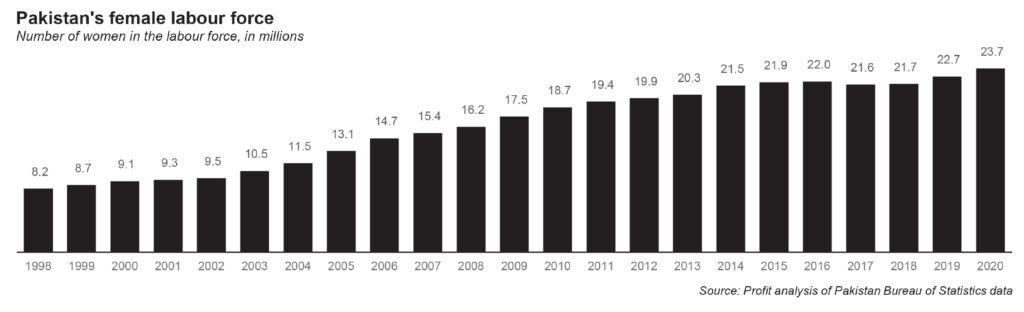

The total number of women in Pakistan’s labour force – earning a wage outside the home – rose from just 8.2 million women in 1998 to an estimated 23.7 million by 2020, according to Profit’s analysis of data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. That represents an average increase of 4.9% per year compared to an average of just a 2.4% per year increase in the total population. In short, the growth in the number of women entering the labour force is more than twice as high as the total rate of population increase.

All of those women now in the workforce have more purchasing power than ever before. Women have always had some measure of purchasing discretion for their households. But now, with their own incomes, they have more ability than ever before to make discretionary purchases for themselves, rather than just making decisions for their households. That includes buying more comfortable undergarments.

And it is not just Pakistan. For context, globally the women’s undergarments category is expected to grow at a compound annualised growth rate (CAGR) of 8.1%, and reach approximately $217 billion by 2022, according to an estimate by Daraz. The Asia Pacific region is going to be a major growth driver, anticipated to grow at CAGR 9.9%, because of higher population growth and increasing per capita income.

So, for this edition, Profit decided to speak to a variety of sellers to create a picture of what the women’s undergarments industry looks like in Pakistan – without shame.

First, let us get some terminology out of the way. The overall umbrella term is undergarments, which are further divided into men’s undergarments, and women’s undergarments, also known as items and clothing you wear under your clothes. Women’s undergarments include, at a basic level, bras (short for brassiere) and panties (women’s underwear).

The term ‘lingerie’ is a subset of women’s undergarments, and typically refers to bras and panties that are more decorative and embroidered, and also robes and nightgowns. This is a loose term however, as the distinction between decorative bras and regular everyday bras has blurred, due to changes in customer preferences and habits in the last 30 years. Everyday bras now also feature lace and decorative trims.

In Pakistan, however, the term lingerie is rarely used to refer to bras, or used in marketing. Most sellers say it is hard for Pakistanis to pronounce the French word ‘lingerie’. That is why decorative bras and matching sets are often referred to as ‘bridal sets’, signifying quality and special-ness. Meanwhile, regular bras in general are often called ‘intimate wear or apparel’, and marketed as such.

The experience of buying a bra in Pakistan can be roughly divided into three: small retailers, large high-end brands, and online. Each has its own consumer base, and challenges.

Small retailers

For most women living in urban centres in Pakistan, it is a man who is likely to sell you a bra. Shopkeepers either have stalls, or small counter shops, in bazaars or shopping plazas, with bras hanging along the store wall, or folded neatly in packs on the counter. There is no room or space for a fitting room to check whether the bra actually fits. Women simply go and have to guess their own size via trial and error.

There are also women-owned, or women-staffed stores that feature the holy grail of bra shops: the glazed door. These are usually bigger stores, also in shopping plazas, that have glazed windows and doors that offer a modicum of privacy, and will also sometimes feature a fitting room. The door often has an elaborate lock, akin to the locking mechanisms on beauty parlour doors in Pakistan: men are not allowed inside these stores at all.

Alternatively, undergarments are bought at supermarkets. Here, men have an advantage – they can simply pick up a pair of boxers in a supermarket and put them in their shopping cart. Women do not have that luxury. Instead, they have to buy bras from a small, secluded department within the supermarket, again closed off to men. The payment is made at a separate counter inside the department, and the bras are packed in brown paper bags. (Ironically, even with a paper bag in a cart, anyone that glances at the cart can tell that there are either pads, hair removal cream, or underwear in that packet, since those are the only items ever stored in a bag.)

Profit spoke to three retailers in Bahadurabad, Hyderi, and Gulistan-e-Johar in Karachi (all three declined to be named for this article). Two were staffed by men, while one was headed by a woman.

While speaking to Profit, the retailers explained that they are far too small to import products themselves. Instead they buy from importers directly, or from wholesalers at Karachi’s Bolton Market.

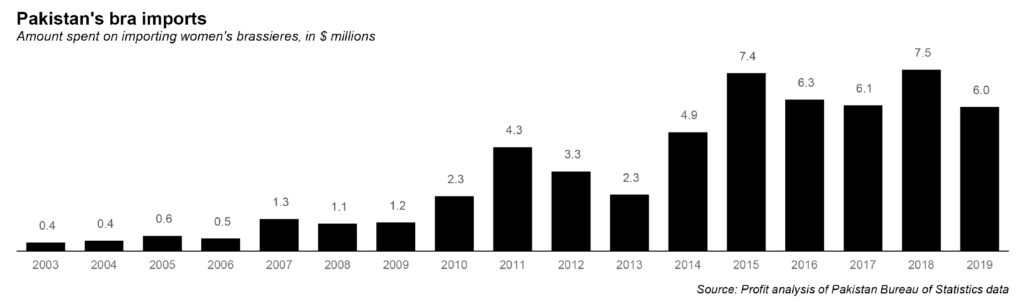

Pakistan’s total imports of bras are a relatively miniscule proportion of the country’s aggregate imports, with just $6 million worth of bras imported in 2019. That number, however, has been rapidly rising, at an average rate of 19.2% per year since 2003, when the country imported just $0.36 million in bras.

A bra’s quality is not related to whether it is imported or not. In fact, imported products can be of cheaper quality, particularly when they are imported from China or Thailand, and are unbranded. When selling them, the shopkeepers refer to them as ‘imported’ but unlike almost every other commodity, this means they are of cheaper quality.

Instead, it is locally manufactured bras offered by IFG and Flourish, that are considered long-lasting and durable. These are typically mid-tier in terms of price, selling between Rs400 to Rs1,000 each.

While panties are considered a running expense and a ‘disposable’ product, bras, on the other hand, are considered investments. Women in Pakistan prefer buying them in bulk, which means roughly three to four at a time, and hope that they last them a year or longer. These are your ‘regular’ bras that you can depend on. While the imported ones are cheaper, those that can afford to choose to invest in IFG or Flourish.

Most customers are both offered, and feel comfortable, buying the standard three colours of black, white or skin color (which is usually not the Pakistani brown skin tone). This is because lawn fabric, the primary fabric used to stitch shalwar kameez for women, is very thin. In order to not be visible, women prefer to avoid prints and designs, and choose these solid colored bras. The idea is that the product is being bought for support and comfort, rather than aesthetic appeal.

Lingerie, which is considered for its aesthetic appeal, is often imported from China. The quality, however, is not durable, and the designs are often very limited. It is difficult to market these products, however, as there are no pictures of the models on the brand.

Are there geographic differences in bra shopping? Yes, actually. While global consumers tend to prefer push-up bras, in Pakistan, there is a massive demand for minimisers or ‘reducer’ bras. This is not simply for women with larger busts – again, due to the thin material of most shalwar kameezes, women are incredibly conscious of appearing too busty, in a society where one’s natural features could be deemed as ‘inappropriate’.

Brands

On the complete opposite end of the price spectrum, are the large retailers and brands, that sell bras for between Rs2,000 to Rs7,000. These are high quality, imported bras that cater to women with greater disposable income, and expectations of a shopping experience comparable to what they have experienced in other countries.

Take Debenhams. The British retailer is operated by an independent third party franchise, Team A Ventures, and was launched 12 years ago in Karachi’s Dolmen Mall. While the store sells clothes and makeup, a full 25% of its annual sales come from its bras and lingerie section. The undergarments section has been wildly popular, among its customer base that can afford the average price tag of a Rs5,000 bra. Debenhams has partnered with global brand Kayser, and its most popular products have been a padded bra that gives extra support and coverage to women, and its panty packs.

Ayaz Arshad, marketing manager at Team A, is frank about why this niche store works: “My customer is someone who is more inclined to buy branded global undergarments over a local one. They often have an emotional attachment to certain brands.”

There is also another, lesser-known reason for its success: “This is the only store where a man can go in and buy a bra in Pakistan… buy it for his wife, his girlfriend.” In fact, according to Arshad, almost half of buyers abroad of lingerie are men. But in Pakistan, most shops are female only, and there is a culture of only women going to buy their own bras (even if the shopkeeper is a man, as mentioned earlier.) “If you had shops where men could also feel comfortable going, you would see sales double.”

However, this is highly unlikely to happen anytime soon; according to Arshad the social and religious stigma about anything to do with bras is too strong, at the moment. Taboos and stigmas force women to put their bras in brown paper bags; but even at fancier shops like Debenhams, social stigma dictates how the company advertises.

“Look, we live in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan,” says Arshad. Though there is no rule or regulation against advertising bras in Pakistan, Arshad says that Pakistan is a conservative society. “This has happened to brands like Tapal and Lipton, a few years ago when some people threw black ash on the models’ faces…there is no way we can have billboards showcasing products [bras].”

And yet, despite the lack of advertising, global bra brands in Pakistan do well. Around six years ago AK Galleria launched Women’secret, which is comparable in price and quality to Debenhams. While Arshad could not comment on specific figures, he did say that global brands all together earn comfortably above Rs10 million in sales a month.

While Debenhams is an established ‘foreign store’, local retailers have also begun to branch into partnerships with foreign brands. Sapphire is the only mainstream large retailer in Pakistan that has started an undergarments section, called ‘Intimate & Sleepwear’, partnering with brand Amante. Though it was launched in December 2019, the idea for the product had been in the works for nearly two years prior.

Investing in undergarments is part of Sapphire’s long-term strategy of being a one stop shop. “A woman should have everything she needs in our store,” explains Kulsum Nabeel.

Kulsum Nabeel was personally frustrated with the lack of options in Pakistan, and thought that high quality bras often had ‘insane prices’. That being said, Sapphire still retails on the pricier side, with bras between Rs2,000 and Rs3,000.

In her market research, Nabeel came to the same conclusions that small retailers have always known: the need for minimisers, and support bras, and to also have a wide variety of skin colour bras, because of the desire to wear lawn kameezes. Women also wanted ‘breathies’, or bras that are breathable and do not feature polyester, which helps in the hot climate. There is also demand for shapewear, which is useful for formal shaadi clothing like saris and lehngas.

Since its launch, Sapphire has catered to all sorts of women. “We have aunties coming in for mature bras, we have younger people coming in for t-shirt bras for their western wear. Our market is everyone who wears a bra,” says Kulsum Nabeel.

Sapphire’s intimate section is tucked away within the larger overall store, yet Kulsum said it was still daunting to some people. “I had family members who refused to go to the store, saying ‘Are you crazy?’ ‘Will everyone know I bought Intimate?’ This social taboo about bras makes people so mortified.” Yet Kulsum is also optimistic that the taboo will go away soon. “Everyone needs bras, there is such a need in Pakistan. And social media has helped educate the customer [and break the taboo],” she says

Online sales

Spot a recurring theme yet? Whether it is a small or a fancy store, everyone seems awkward about going into a store and buying a bra. But online, one has no such qualms. Even Nabeel, who had spent the better part of two years testing out materials and fabrics, was surprised how quick customers were to buy bras from Sapphire’s online store, without ever once having touched the product.

Daraz, which launched in 2012 in Pakistan as an online marketplace, has benefitted from this customer behaviour. In e-mailed responses to Profit, Imran Saleem, commercial director at Daraz said, “We saw a major uplift in sales of this category in the past few years as a shift in consumer buying behaviour, people became more receptive towards online shopping. A lot of women are shy about purchasing intimates in person and therefore are more comfortable buying online.”

A few statistics: Daraz sells over 15,000 products within the intimate apparel section, (though this number can go up in flash sales), of which bras make up 40% of all sales. The most popular products are made of cotton, and the average price point hovers between Rs900 to Rs1,300 each. Around 65% of all sales are done by marketplace sellers. Only a small chunk is locally produced, while most are imported products mainly of Chinese and Thai origin. Most customers at Daraz are between the ages of 21 and 36.

Taboos persist: for instance, women tend to give only anonymous reviews on intimate products. According to Saleem, many women use Daraz profiles of their male family members to place orders.

“Taboo surrounding intimate products depends entirely on the pictures used. Decent pictures of just the product itself is viewed to be okay. However, pictures with models are considered taboo. If we’re able to tackle this issue mindfully, we will be able to lift the taboo surrounding the selling of intimate products.” Daraz’s biggest challenge is in fact trying to clamp down on the use of ‘indecent and inappropriate’ pictures to market bras online. “As there are thousands of such lists and hundreds of news ones are added every day, it’s very hard to keep a check and balance of the kind of images marketplace sellers use to advertise intimates.”

Still, women continue to shop online for perks like competitive price points, and size charts on product display pages. The pandemic also helped boost sales, as more people bought and wore sleepwear and bras.

“It is more convenient to buy through an online platform than to visit a brick and mortar store. Consumers these days are extremely promo driven, and online platforms usually offer multiple promos throughout the season to keep up with the sales,” explains Imran.

The future

So, what does the future look like? For places like Debenhams, the plan is to expand into other cities, like Lahore and Islamabad. Arshad even hinted at opening a Victoria’s Secret-esque megastore in Pakistan, tailored to local needs and sensibilities. For places like Sapphire, it is about expanding the limited collection and building upon an already loyal customer base.

But these are just some individual goals. The undergarments industry is going to see rapid change in the next five years. According to Daraz, Pakistan has a young population with a median age of 24 years and a high marriage ratio. There is going to be a surge in demand for bras and lingerie by young couples over the next five years. And then, there is the simple fact that as Pakistan’s population grows, more young girls will transition into adulthood, which means more bras.

Clearly, there are bras being sold at various price points in urban markets. That is not the problem. The challenge is instead in creating an environment where it is seen as completely normal to market, sell, and buy undergarments. Really, folks, it is just a bra.

Fleeking story of the entire week

Keep it up

Thanks for your post. Jontis World is best underwear store in UK

32 number bra Ajk mzd gijra baba baker

It is very awkward to buy a bra in Pakistan.

Once,I had to buy a bra for a female family member and it was a traumatizing experience for me and I am a fat hairy dude with a big beard. The shop was run by an aged aunty,I went to her and whispered what I was asked to bring,well she started talking about different types of bras instead of giving me what I asker and it was getting very awkward for me,so after all that when she handed over the first bra to me,I only said how much,paid her,then she put it in a black plastic bag like it was something illegal like a bomb or explosives and I just bolted back to home. I handed over the bra to whom had asked me to bring it for her as she is very shy to go out and buy one herself. It is the most awkward moment of my life till now.

A man should be able to buy a bra without any judgement.

One of the best articles i`ve recently came across regarding Ladies undergarments. Well written and to the point.

This is the proud moment.