Three years ago, it seemed like Alfalah Bank was on the chopping block. Alfalah’s parent group, the Abu Dhabi Group, was in talks with a variety of buyers to potentially sell the bank. And why not? For years, the medium sized bank had been punching exactly its weight, and was brimming with the potential to crack the ranks of the big five banks; now it had slipped in the ranking, losing market share.

Despite the rumours of Bank Alflah being sold, here we are in 2021, with the bank very much intact. Not only that, but the group has recently decided to bring back Atif Bajwa, who had been the president of the bank for over five years before resigning in June 2017, for personal reasons. He was brought back to helm the bank in February 2020.

On one hand, the decision seems strewn with all kinds of baggage and complication. Why would Bank Alfalah go from being on the market to bringing back a former president to steady the ship? But on the other hand, the decision makes sense. Those three years away from Alfalah have given Bajwa time to reflect. When asked in a recent interview with Profit whether anything had changed in his time away, Bajwa had the etiquette to be reticent about his predecessor, but that did not mean he was shy about discussing the path the bank had been on.

“What I didn’t like was certainly the fact that we had lost market share. I think we have in our people a desire to be ahead. We don’t want to see anybody else in the race getting ahead of us. So there’s that competitive spirit that made me feel, you know, maybe we’ve lost it a little bit. What could we have done better? What are things that need to be addressed? And that’s where strategy comes from.” he said.

If one reads between the lines, it’s clear what message the group wants out: Bank Alfalah is back, and it is coming for what it lost and more. But can the rejuvenated Bajwa help Alfalah regain lost ground?

History of the bank

Much as all roads lead to home, most banking careers and stories in Pakistan from the 1990s and before lead to the Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI). The BCCI is also where the story of Bank Alfalah starts. The Bank of Credit and Commerce International was one of the most notorious banks in the recent past of the global banking system and it started in Pakistan, founded by Agha Hasan Abedi, a man who got his start at Habib Bank in 1946, but then went on to create United Bank Ltd (UBL) in 1959, and the BCCI in 1972 after UBL got nationalised.

The BCCI started off from an office building on Karachi’s McLeod Road (in what is now Bank Alfalah headquarters) but quickly grew to become the seventh largest private bank in the world, along with it introducing an entire generation of Pakistanis to the world of international banking. The alleged fraud that caused British regulators to shut down the bank in 1991 is, of course, now a well-documented part of banking history, but it did have a significant legitimate business that left orphaned assets in its wake after the bank was disbanded worldwide.

In Pakistan, its assets consisted of three branches in Karachi and Lahore. The State Bank of Pakistan took over those assets in 1992 and renamed them Habib Credit and Exchange.The move to seize BCCI’s Pakistan assets coincided with the deregulation and privatization of the Pakistani banking sector. In 1997, Habib Credit and Exchange was bought out by a new banking entity backed by Middle Eastern investors: Bank Alfalah.

Bank Alfalah’s majority shareholder, with approximately 22% holding, is Sheikh Nahyan bin Mubarak Al Nahyan. His brother, Sheikh Hamdan, has been the chairman of BAFL’s board since 2002. Both brothers are minor members of the UAE federal cabinet.

Historical financials

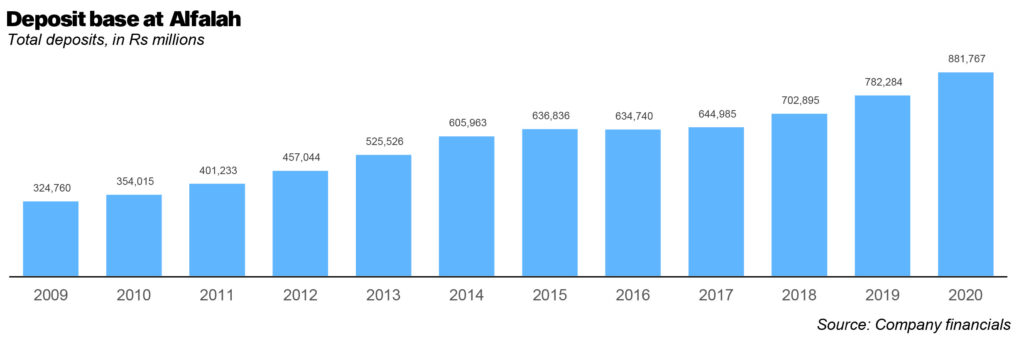

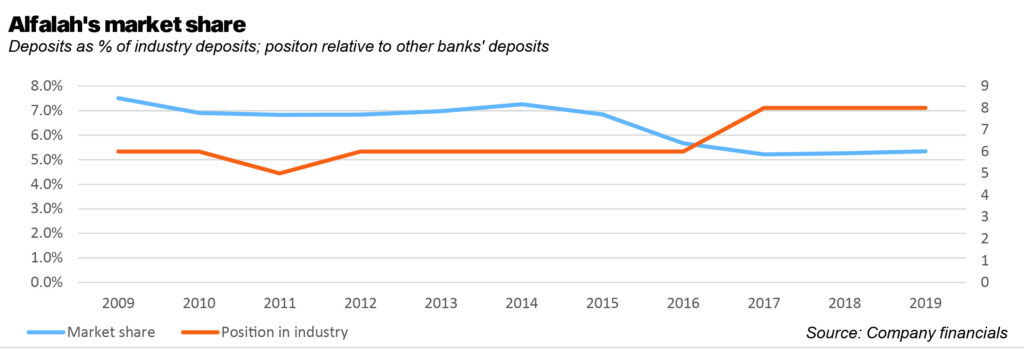

Bank Alfalah grew from almost nothing to being one of the largest banks in Pakistan. In 2005, only seven years into existence, overtook Allied Bank to become the fifth largest in the country in terms of total assets. A deeper dive into the last decade shows some interesting trends. First the bank’s deposits have been steadily increasing since 2009, when deposits stood at Rs 324 billion. In particular, deposits grew 13.9% year-on-year in 2012, and at 15% year-on-year in 2014. Deposits crossed the Rs500 billion mark in 2013, and the Rs700 billion mark in 2018, and finally, crossed the Rs800 billion mark in 2020. Growth in deposits stagnated in 2016 and 2017, before jumping again in 2019 and 2020.

If one looks at the deposits as a share of the total deposits in the banking industry, Alfalah Bank’s share has actually fallen. In 2009, the market share stood at 7.5%, the highest share it would ever have. It would hover between 6% and 7% until 2015, and then fell to the 5% range for the next five years.

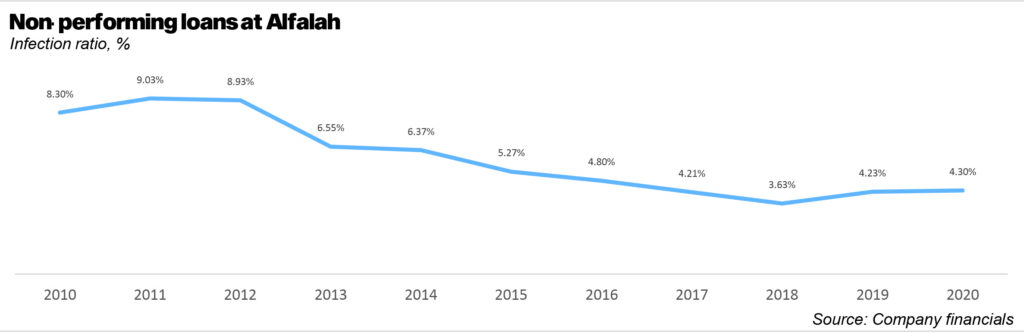

The bank’s non performing loans have mostly been under control. For every year between 2010 and 2019, the ratio of the non performing loans to gross advances has been significantly lower than the industry average. In 2010, non-performing loans made up 8.3% of all loans; this fell to 4.8% by 2016, and has been maintained in that range ever since. In 2020, non-performing loans were contained to just 4.3% of gross advances.

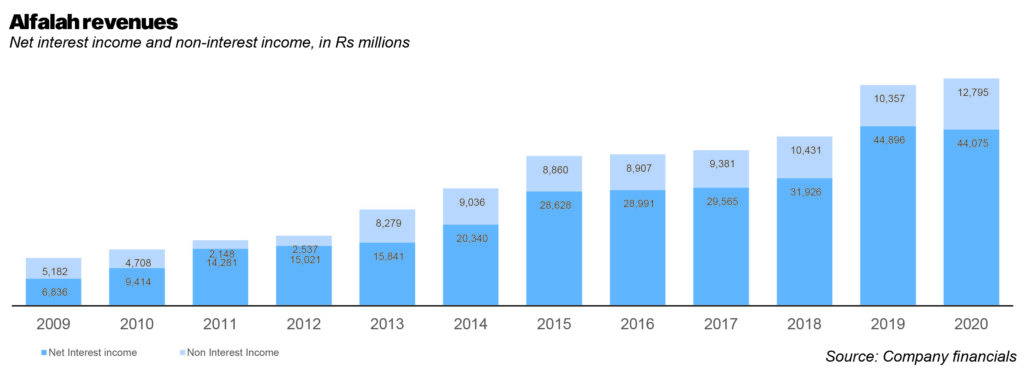

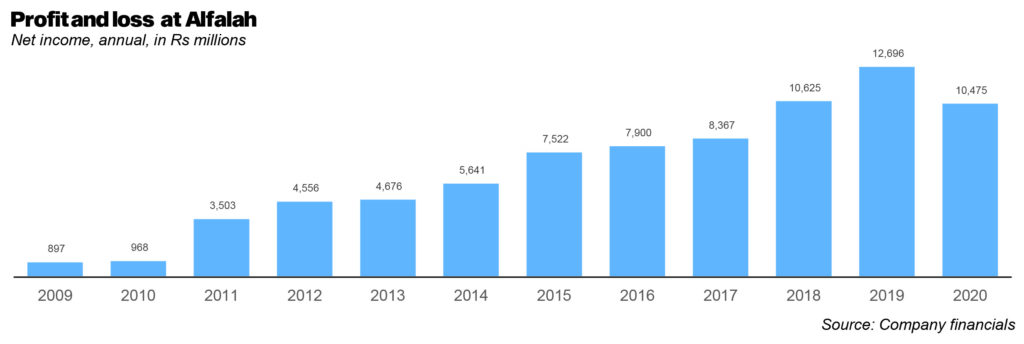

Between 2012 and 2015, Alfalah Bank saw its revenues jump from the roughly Rs17 billion range to around Rs37 billion. Revenues would stay there until 2019, crossing the Rs50 billion mark. A similar trend can be observed with the net income at Alfalah Bank, which has hovered between the Rs7-8billion range between 2015 and 2017, and then crossed the Rs10 billion mark in 2018.

The CEO switch

To lead this decade, the group brought in Atif Bajwa, a veteran banker with a professional career spanning three decades. Bajwa was previously the president and CEO of MCB Bank Ltd, president and CEO of Soneri Bank Ltd, and country manager for ABN AMRO Bank. He has also served as chairman of the Pakistan Business Council and as president of the Overseas Investors Chamber of Commerce & Industry. Perhaps most importantly, in the Pakistani banking context, he is an ex-Citi banker, having joined that bank in 1982. That bank has been an incubator not just for leader’s in Pakistan’s banking ecosystem, but for overall financial leadership as well, producing more high-profile CEOs of the current banks in Pakistan, as well as finance ministers and one Prime Minister in the shape of Shaukat Aziz. Add to these credentials that Bajwa is arguably the most high profile bank president in the industry right now.

Yet his tenure at Bank Alfalah was somewhat complicated, and controversial. Some historical context may be necessary. As mentioned before, Bank Alfalah is owned by the Abu Dhabi Group. Within Pakistan, it not only owns Bank Alfalah, but also the telecom company Wateen, and has minority stakes in Jazz (which it is selling back to VEON, the majority owner of Jazz), and also real estate projects worth several hundred million dollars, though many of these projects have been on standstill for several years now.

Yet despite his contract having been extended for another five years, Atif Bajwa surprisingly resigned in June 2017, citing personal reasons. Instead, the former CEO of Faysal Bank, Nauman Ansari, was appointed as his successor. As the numbers will reveal, under Bajwa, Bank Alfalah had grown rapidly. And yet industry insiders had previously told Profit that Atif Bajwa did not get along with Adeel Bajwa, then CEO of the Abu Dhabi group.

Adeel Bajwa had been made the CEO of the Abu Dhabi Group in 2016, and had been associated with the Dhabi group for more than a decade, helping with mergers and acquisitions for the group in South Asia and Africa. Reportedly, Adeel Bajwa had told Atif Bajwa that Bank Alfalah was spending too much money. The Sheikh sided with Adeel Bajwa, due to his long history with the firm.

But why did it matter whether or not Bank Alfalah was spending money or not? Well, that is because given the struggles of its telecom businesses, it has long been rumoured that the Abu Dhabi Group may decide to close shop in Pakistan altogether and even sell off Bank Alfalah.

It was in this interest in selling off Bank Alfalah which is said to be behind Atif Bajwa’s departure as CEO of the bank in June 2017. Sources inside the bank say that he had been under tremendous pressure to reduce operating costs and had been unable to do so, in part due to his desire to protect the exceptionally strong benefits that the bank offers to its employees, matched in their generosity only by the state-owned National Bank of Pakistan.

It is not a coincidence that the man brought in to replace Bajwa was Nauman Ansari, the man who was responsible for removing an estimated Rs1.5 billion a year in excess operating costs from Faysal Bank’s income statement. Ansari served as CEO of Faysal Bank from 2014 through 2017.

In bringing in Ansari, the sponsors sent a clear signal that the bank’s operations were being made more efficient and profitable in preparation for a sale. Higher profits are likely to result in a higher sale price for the Abu Dhabi Group’s shares in the bank.

Except, as we now know, this never materialized. According to industry insiders, the group was in talks with at least four potential buyers: Faysal Bank, Habibullah Khan’s Mega conglomerate, Arif Habib, and a consortium headed by Sameer Chishty. In all four cases, a deal never materialized, because no party could agree on the pricing. In the case of Faysal Bank, the idea was to merge the two banks, while according to a source the Hong Kong based Sameer Chishty led consortium was also trying to buy both Bank Alfalah and Faysal bank and merge the two together. (Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article erroneously claimed that Syed Babar Ali’s IGI group was part of the Sameer Chishty led consortium. Chishty has denied this. The error is regretted.)

While this was ongoing, Adeel Bajwa himself resigned (somewhat unceremoniously) and left the Dhabi group in March 2019. With one Bajwa’s departure, perhaps it was now time to turn to the other Bajwa, to helm Bank Alfalah once more.

For his part, Bajwa mentions none of this convoluted history, and is nothing but supportive of the group: “I think we have a great board now. Most of them are the same people and they’ve been very supportive, always. They look for ideas to come from management and then they support them or disagree, or adjust, which is how a professional board should run. And you know, obviously everybody relies on the chairman’s guidance and support and he’s been very, very good and he’s got a direction for growth.”

The year 2020

What about the financials for the year that Bajwa finally returned? A deeper dive reveals that despite a higher revenue than last year, the bank’s net income is lower than last year’s – in fact, it is the first time in seven years that the bank’s after tax profit has decreased compared to the year before.

Let us break this down. In 2020, the bank’s net interest income stood at Rs44.7 billion, which is comparable to 2019’s net interest income of Rs44.9 billion. The bank’s total non-interest income is, in fact, much higher, at Rs 12.8 billion, compared to 2019’s Rs10.4 billion. Within that category, the bank’s fee and commissions income increased from roughly Rs6 billion in 2019, to Rs6.6 billion. The bank’s dividend income also increased from Rs338 million in 2019, to Rs403 million. And finally, the bank experienced a significant gain from securities, jumping from just Rs64.8 million in 2019, to Rs2.3 billion in 2020.

That is how the bank’s total income increased from Rs55.2 billion in 2019, to Rs57.5 billion in 2020. So, what happened? Essentially, the bank’s expenses went from Rs29.8 billion to Rs32 billion. Then, the bank’s provisions went from Rs3 billion to Rs7.6 billion. This was enough to tilt the bank’s net income to below 2019 levels.

According to the bank’s annual report of 2020, the bank’s non mark up expenses were driven by higher staff costs, IT support and maintenance fee, and the full year impact of the new branches which were opened in 2019, was finally realized in 2020. This meant the cost to income ratio of the bank went to 54.7%, which is higher than that of 2019’s.

But the main cost is, of course, the provisions: To that, the director’s report noted that “During the year, in addition to subjective provisioning against clients showing credit weakening, the bank has taken a general provision of Rs4.25 billion. Given an uncertain economic environment, the bank anticipates that several borrowers will be impacted due to the pandemic. Many such borrowers have availed the SBP enabled deferment and rescheduling relief, however, since the full potential effect of the economic stress is difficult to predict, this general provision has been created as a buffer for the following year.”

The bank added that the loans with principal over Rs52 billion were rescheduled under the SBP loan, and over Rs29 billion of fresh loans backed by the SBP refinance scheme were provided to over 300 entities. This is ultimately a good sign for analysts, who say that booking large provisions usually is a good sign for banks, and means they are cleaning the books. Bajwa reiterated the stance on provisioning, saying that the provisioning number was introduced to withstands any shocks from the fallout of Covid-19 pandemic.

“Look at our NPL-coverage ratio. We had come down to about 79%, which in our assessment was probably a little bit lower, and certainly was lower compared to the industry. So we wanted to bring that up into the nineties. And so this extra provisioning also helped us get to 91%. So now we’re feeling comfortable that our provisioning position and coverage is at the right level. We don’t foresee any major shocks and the provisioning that we’ve taken will also help us,” said Bajwa.

Problems with the bank

As far as Bajwa was concerned, the bank had lost its way on two major aspects. The first, of course, are the financials. But other than this, Bajwa saw that the bank had taken a major blow in terms of bank culture.

“It really was a tough year financially for the bank, especially when you look at it on a relative basis,” he says on the financial side, without mincing his words. “So the question is what was different for us? When we were growing our market share, we had started competing for the fifth position in terms of size of the market share. And you know, we were very close to being overall number five. Now we’ve ended up being number eight now.”

“If you look at what’s happened in the banking industry over the last few years, we’ve seen that a number of our competitors have increased their growth momentum. We want to get the momentum back in and the energy back. And so the number one of course is that we have to slowly regain market share in various products:, not just deposits, but its lending, its consumer products, its payment products, SME.”

But to drive a bank, one needs people. As that famous management quote goes: “Culture eats strategy for breakfast”. And the culture had Bank Alfalah, according to sources, had stagnated. Employees continuously left for other banks. Allegedly, Bajwa had been unhappy with few of the group heads on his return, promising to shuffle or remove some (when asked about this, Bajwa denied the anecdote, and said it would be unfair to single out any one group head). On the same count, sources have mentioned a more active, hands-on approach now that Bajwa is back, and the beginnings of a slight cultural shift.

For his part, Bajwa is acutely aware of the bank’s culture problem.

“[People] need to be driven by a common culture. That’s driven by caring for customers…ambition, progressive attitude, innovation, high energy and extremely importantly, by teamwork and solution orientation. When an organization goes through frequent changes you tend to lose focus [on those]. So we want to bring that focus back in and certainly build that consistent, sustainable culture that drives an organization forward.It’s really based on making sure that our people’s strengths are strong, that they have career progression, if they feel they have personal enrichment, and whether they feel comfortable in this culture.”

When asked if the bank’s human resources department could have done better, Bajwa resisted: “It’s probably not fair to just blame the HR department for, if there is any level of unhappiness in the organization, it comes from the atmosphere and the culture that gets developed. And as a leader I would have to take personal responsibility. So I would never be able to say that my HR is not doing a good job, because it would be my job to make sure that there is an atmosphere developed and there’s a culture developed where everybody feels that they have to do the right thing by the customer and by the employees.”

The future

In conversation, Bajwa continuously referenced the bank’s digital strategy: “One of the key pillars is digital banking, and investing in the future of financial services. Going forward we have a strong position in terms of what we have developed and probably the richest range of products and services that are digitally offered today.”

Bajwa said that Covid-19 had helped transition more customers from physical transactions to digital transactions. However, the internal processes needed to now be driven digitally. “We just need to keep on pushing that frontier of what we can do as a bank based on technology.” To that end, Bajwa said the bank was in conversations for partnerships with fintechs, though he did not disclose names just yet. As he puts it: “Banks are good buyers of technology. They’re not necessarily great innovators or creators of new solutions.”

Instead, it is startups and fintechs full of “young, energetic, nimble people who are coming up with new ideas.” And the new generation is much more comfortable with technology. Bajwa sees enormous potential in that age bracket, and thinks fintechs will help bring value to new customers.

But one must take a step back and reflect: why is Bajwa dropping buzzwords? ‘Digital’, ‘Market Share’ – these are the words of a bank that is here to stay. Bajwa is also cautious, caveating each reference to growth with a ‘slow and steady’ approach. It is as much a signal to the group about his expected performance, as it is to the market.

Except – the market has not reacted as well to Bajwa’s return, as it did to Ansari’s appointment. Perhaps then, it was clear that the bank was being sold, and that it would fetch a multiple of around 2 on the going market price of the share. And perhaps now, it is clear that there is no deal in sight. But also there was no clear understanding of Bank Alfalah’s path forward, or why Bajwa is even back.

Well, now we know. Can the bank become competitive enough to give the big five banks a run for their money? Two other banks have come close, as Profit has previously covered. Meezan Bank had deposits of just Rs3 billion on December 31, 2001 while Bank AL Habib had nearly Rs25 billion. And yet as of June 30, 2020, the latest period for which both banks’ financial statements are available, Meezan Bank had deposits of Rs1,045 billion to Bank AL Habib’s Rs1,042 billion. Meezan overtook Bank AL Habib as the sixth largest bank in Pakistan by deposits in 2019.

In contrast, Bank Alfalah is the eighth largest bank, as mentioned by Bajwa himself previously. Can it climb the ranks again? Bajwa and the group are betting on it.