If there is one thing the last 10 years have demonstrated, it is this: the country appears to have a shortage of people who are deemed worthy of serving as Finance Minister. Why else would the Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf (PTI), which railed against all of its political rivals, end up recycling not one but two of the Pakistan Peoples’ Party’s (PPP) finance ministers after a rocky start with one of its own?

This magazine has previously profiled what the job of the finance minister entails, which we initially did when the Imran Khan Administration first came into office. As we approach the final two years of the current term of the administration, with the finance ministry helmed by a man who first held this office more than a decade ago under a very different prime minister, we thought it would be good to look at not just who has previously held the job, but who are the leading contenders to hold the job in the future.

This article also has a very specific political agenda which we will state up front: we would very much like for Abdul Hafeez Shaikh to never become finance minister again, and if we can avoid having Shaukat Tarin return to the job after this particular term of his ends, we would be grateful for that as well. Nothing against either gentleman, but we would like to see some fresh talent occupy the top corner office in Q Block.

What we will outline instead are a few names of people who are currently serving in the trenches in other posts in government – some more prominent than others – who form a talent pool from which whoever the next prime minister is can pick their next finance minister.

To start our conversation, we will first lay out who has occupied the office in the past, why we think there is a vacancy now, and who are some of the leading candidates to fill those vacancies. We also want to be very specific: in no way are these people the ones we think are the best or most qualified, though many of them are well-credentialed. This is simply our best guess for a list of names that is likely to come under consideration for finance minister the next time a cabinet is formed.

Who wants to be Finance Minister?

Before we dig into who we think will become finance minister in the future, let us dig into who has become finance minister in the past. The list and profiles of the office holders in the past is quite illuminating with respect to the qualities we have sought in the person placed at the helm of what is probably the most important ministry in the federal government.

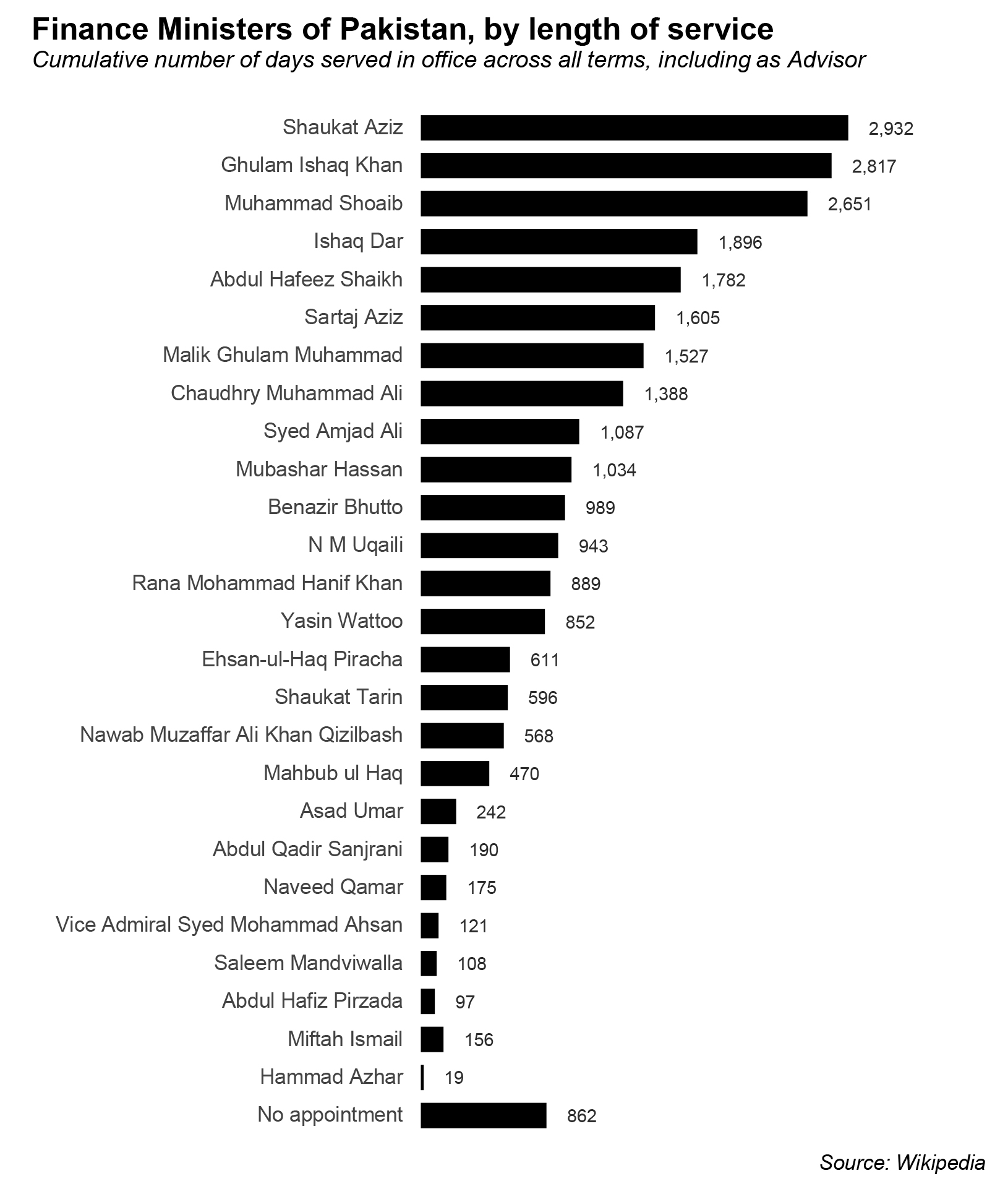

A total of 30 people have ever served as Finance Minister of Pakistan, though for the purposes of our analysis, we are counting people who served as Advisor to the Prime Minister on Finance as the full minister because, effectively, that is what they were. This list of 30 includes four people who served as interim finance minister in between governments.

Of those 30, only two women have ever served in the finance ministry. One was Shamshad Akhtar, the former State Bank Governor who briefly served as interim finance minister before the 2018 election. The only elected woman who ever served as Finance Minister was when Benazir Bhutto served as her own finance minister in the 1990s. No man has ever appointed a woman to this position in cabinet. Ever.

Since Partition, the ministry has been left unoccupied for a total of 862 days (a little over two years) in between various appointments. That is a rather long time to have left this vital ministry unattended, but then again, take a look at how long we have gone without an elected prime minister, and you feel less bad for this ministry.

So how long has the average minister been in office? Well, excluding the ones explicitly appointed as interim ministers, the average finance minister has spent about 990 days (a little over two years, 8 months) in the job. This, however, counts multiple stints for the same person as one, which probably overstates the level of stability there has been on this job.

However, the average is hiding some important details. For instance, the three longest serving finance ministers of Pakistan were all ones who served under military dictatorships. In descending order of the length of their time in office were Shaukat Aziz (President Musharraf), Ghulam Ishaq Khan (President Ziaul Haq), and Muhammad Shoaib (President Ayub Khan).

The longest serving democratically elected finance minister is Ishaq Dar, though that is across three terms in office. All told, Dar served about 5 years, 2 months as finance minister. The next longest serving is Abdul Hafeez Sheikh, who, across two terms, served about 4 years, 11 months on the job. The third longest democratically elected minister was Sartaj Aziz, who served in Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s cabinet in that role in the 1990s.

We will exclude the dictators’ ministers, since we believe there will never be a military government in Pakistan ever again. What do the democratic ministers have in common? They all had some vaguely ‘economic’ work experience prior to being assigned the ministry and were already close to the Prime Minister who appointed them. None of them were appointed solely because the incoming Prime Minister believed they would be the best person for the job, and did not otherwise have a previous relationship with them.

That pattern, we believe, was both bad for the country, and likely about to change in the future. And that brings us to the subject of the Vacancy.

The Vacancy in (most) political parties

It has happened at least partly by accident and partly because the government of Pakistan systematically decided to not invest in educating our population since Partition. But the result is that, of the three major political parties in Pakistan, there is now no clear designate for Finance Minister of Pakistan in two of them. Let us explain what we mean by that.

While Profit generally tries to stay away from political analysis, it is likely a fair assessment that the three biggest political parties in Pakistan, and the ones that have the highest probability of winning and election and forming a government, are the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), the Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PML-N) and the Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf (PTI).

Of these three, only the PML-N has a clear favourite for who would become finance minister if the party were to win the next general election. Assuming the PML-N wins in either the 2023 or the 2028 elections, it is very likely that Miftah Ismail will become the finance minister.

Who will be the nominee for either the PPP or the PTI? For the PPP, it is obvious that there is no clear frontrunner. They might plug in Abdul Hafeez Shaikh again for lack of any other options, but there is no clear party member who would be appointed to the job.

(Note: Abdul Hafeez Shaikh is the Microsoft Internet Explorer of cabinet ministers. If you do not select a better option, he is your default setting. He comes with the operating system.)

For the PTI, you might say: well, if they win re-election in 2023, they will likely continue with Shaukat Tarin. That is certainly possible, and even likely. But what if they lose and then win in 2028? Who is the nominee? It is unlikely that Tarin, who would be 75 then, would be available to serve for a third term in a very grueling job. Who then? There are many guesses, but no one clear answer.

Wait, you might say. There is no clear designate for any cabinet position for any political party. So why this article?

Because unlike the other ministries, there is now a convention in Pakistan – similar to other parts of the world – that the finance ministry at least requires some semblance of technical expertise. Other ministries could benefit from ministers who were familiar with the subject matter under their jurisdiction, of course, but such a convention has not yet been established for those cabinet positions, which tend to be awarded on the basis of political considerations more than technical merit or managerial talent.

So who are the next generation of economic leaders in Pakistan? Who is likely to be on the shortlist for Finance Minister of Pakistan? Let us dive into the list.

The List: Leading PTI Contenders

Of the list of people who might conceivably get the job in the near future for the current ruling party, there are three names that we believe have a somewhat higher likelihood of landing the job, based largely in part on where they are now, and their actions since having achieved the current positions they hold.

Makhdoom Hashim Jawan Bakht: The current finance minister of Punjab is one of the young guns of the PTI who has both the professional resume and the political credentials to make a strong contender for the Finance Minister job in Islamabad. In terms of professional credentials, he spent the bulk of his career as an investment banker at Citigroup. He has an undergraduate degree from McGill University, arguably the most prestigious university in Canada.

Makhdoom Hashim Jawan Bakht: The current finance minister of Punjab is one of the young guns of the PTI who has both the professional resume and the political credentials to make a strong contender for the Finance Minister job in Islamabad. In terms of professional credentials, he spent the bulk of his career as an investment banker at Citigroup. He has an undergraduate degree from McGill University, arguably the most prestigious university in Canada.

But, of course, his professional credentials are not what got him the job. There were probably at least a dozen people with the same or better educational and professional experience than him, even out of his own class at Aitchison. What makes Bakht interesting is the fact that he is from a politically prominent family from Rahimyar Khan, the kind that can win an election without having a political party affiliation. Bakht previously served as a PML-N member of the Punjab Assembly before switching sides and joining the PTI in 2018. His name is routinely floated as a potential future chief minister of Punjab, and in the event that the PTI has to rely on anyone other than Tarin, his name would be on the very shortest of shortlists for federal finance minister. Born in 1979, Bakht is only 41, so he has a long political career ahead of him.

(Editor’s note: Bakht’s elder brother Khusro Bakhtiar is currently a federal minister in the PTI cabinet, and considering the family’s ever changing political associations in the past, either of the brothers can be the candidate of choice from any of the three leading political parties.)

Taimur Khan Jhagra: As the finance minister of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, the 43-year-old Jhagra is a strong contender for promotion to the federal job, and would probably have been the leading contender had he been from Punjab. Nonetheless, in terms of professional credentials, Jhagra’s resume reads even more impressive than that of Bakht.

Taimur Khan Jhagra: As the finance minister of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, the 43-year-old Jhagra is a strong contender for promotion to the federal job, and would probably have been the leading contender had he been from Punjab. Nonetheless, in terms of professional credentials, Jhagra’s resume reads even more impressive than that of Bakht.

Jhagra got an undergraduate degree in mechanical engineering from the Ghulam Ishaq Khan (GIK) Institute of Engineering Sciences and Technology in 2000. Following his undergraduate degree, he got a job as an engineer at Schlumberger, the global oil field services giant. After six years at that job, he then got an MBA from London Business School, one of Europe’s two best MBA programs, in 2008, following which he joined McKinsey & Company, the formerly prestigious management consulting firm.

Jhagra rose fast through the ranks of McKinsey, rising to the coveted rank of partner before quitting to launch his political career. That ambition, of course, was helped by the fact that he is son of retired federal secretary Saleem Khan Jhagra, nephew of late PPP leader and provincial minister Iftikhar Jhagra and grandson of Ghulam Ishaq Khan, the influential bureaucrat who served as President of Pakistan between 1988 and 1993 and was the second-longest-serving federal finance minister under Ziaul Haq, from 1977 to 1985.

Reza Baqir: A bit of a political outsider, Reza Baqir is the current Governor of the State Bank of Pakistan, which would not normally rule him in the running for the finance ministry job, but Baqir is more overtly political – and more openly aligning himself with the Prime Minister – than is the norm for a person in his position. Clearly, the central bank governorship is not the end of his ambition.

Reza Baqir: A bit of a political outsider, Reza Baqir is the current Governor of the State Bank of Pakistan, which would not normally rule him in the running for the finance ministry job, but Baqir is more overtly political – and more openly aligning himself with the Prime Minister – than is the norm for a person in his position. Clearly, the central bank governorship is not the end of his ambition.

In terms of academic and professional credentials, Baqir is no lightweight. The second Aitchisonian on this list, he got his undergraduate degree at Harvard, and a PhD in economics at the University of California at Berkeley. Following his PhD, Baqir worked both in academic positions and eventually as an economist at the International Monetary Fund (IMF), a position he held for almost two decades.

Unlike the previous two, he does not have the same kind of political family connections. And no State Bank governor has gone on to become the finance minister, though there is recent global precedent for such a move: former United States Federal Reserve Chairperson Janet Yellen recently became the US Treasury Secretary.

And unlike his predecessors on the job, Baqir does not behave like a neutral technocrat but rather more like a political appointee, somewhat akin to a junior minister rather than an independent central bank governor.

Hammad Azhar: At 19 days, Hammad Azhar’s tenure as federal finance minister is the shortest one in Pakistani history. And for a junior minister to be turned down for the senior job might ordinarily have been taken to mean that his prospects for the top job are over. But we cannot rule out the 39-year-old Hammad Azhar for a variety of reasons.

Hammad Azhar: At 19 days, Hammad Azhar’s tenure as federal finance minister is the shortest one in Pakistani history. And for a junior minister to be turned down for the senior job might ordinarily have been taken to mean that his prospects for the top job are over. But we cannot rule out the 39-year-old Hammad Azhar for a variety of reasons.

Firstly, he may not have been given the finance ministry job, but he was given the prominent, if somewhat amorphous federal energy ministry, suggesting that he is politically important enough to be granted a senior cabinet member position. It helps that he is the son of former Punjab Governor Mian Muhammad Azhar and delivered an important constituency from Lahore to the PTI.

A graduate of the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) of the University of London and Lincoln’s Inn, Azhar’s professional credentials are somewhat lighter, though he appears more comfortable publicly defending the government in contentious policy matters than some of the other contenders, which is very likely a point in his favour.

Yes, he is an Aitchisonian too.

The List: The PML-N’s man

Miftah Ismail: Unlike the other names on this list, the only thing that will determine whether or not Miftah Ismail gets the job is whether of not the PML-N wins the general election. If that happens, it is all but certain that Ismail will get the job, just as he held it in the final days of the Nawaz Administration.

Miftah Ismail: Unlike the other names on this list, the only thing that will determine whether or not Miftah Ismail gets the job is whether of not the PML-N wins the general election. If that happens, it is all but certain that Ismail will get the job, just as he held it in the final days of the Nawaz Administration.

The 49-year-old Karachiite has a PhD in public finance from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, and worked as an economist at the International Monetary Fund for three years before returning to home to Karachi to run his family business, the publicly listed Ismail Industries, a confectionery manufacturer with a market capitalization of over Rs27 billion.

Miftah got the job when Ishaq Dar was ousted, and given how much legal trouble Dar is in, combined with how much he is reviled by the country’s business community and how much Ismail is trusted, it is all but certain that Ismail will get the finance ministry job if his party wins the election. The PML-N may still be debating who to run for Prime Minister, but they already have their finance minister sorted.

While Ismail is not from a political family himself, he has tried to run for the National Assembly from his home constituency in Karachi, but lost the 2018 election as well as his by-election.

The List: Slim pickings for the PPP

Syed Murad Ali Shah: Why on earth would the Chief Minister of Sindh want the federal finance ministry job? Because his party might need him to. Of all the political parties who are in desperate need for candidates for finance minister, the PPP is the most desperate, because their leading contender is a man they equally desperately need for his current role.

Syed Murad Ali Shah: Why on earth would the Chief Minister of Sindh want the federal finance ministry job? Because his party might need him to. Of all the political parties who are in desperate need for candidates for finance minister, the PPP is the most desperate, because their leading contender is a man they equally desperately need for his current role.

Murad Ali Shah has politics in his bloodstream. He is Chief Minister of Sindh and the son of a former Chief Minister of Sindh, Syed Abdullah Shah. He is also as Karachi as they get: an alumnus of St Patrick’s High School and NED University, from where he got a degree in civil engineering. He then got not one but two masters degrees from Stanford University.

He worked as a structural engineer for the Water and Power Development Authority, the Port Qasim Authority, and the Hyderabad Development Authority before switching careers completely and going on to work as a banker at Citibank in Karachi and London.

In the event that the PPP wins a general election, their only serving chief minister is also their only candidate for finance minister, assuming they decide not to go with Hafeez Shaikh. He is also probably the only candidate who might be passed over for the job because his party cannot decide on a replacement. (It is a remarkably precarious balance in Sindh for who can get the Chief Minister job without annoying all the factions of the PPP.)

What the list means

We would like to highlight the fact that the top names all have something in common: they all have extremely impressive professional and educational credentials, and many of them even have political connections through their families, as the sons of prominent politicians and civil servants.

(Did we say “sons”? Yes, we did. There are no women on our list. We did not say this is the way things should be, merely the way they are.)

Why does that matter? Because it used to be that the only thing that mattered was how strong your political connections were. But as Pakistan’s political elite has grown in size, with a larger number of heirs vying to succeed their parents, there is now internal competition within the elite for the top jobs, and a restricted kind of meritocracy that is beginning to take shape.

There are probably dozens of young political aristocrats who graduate from Aitchison every year, but the ones who are leading contenders for the finance ministry are the ones who were good enough to do well as bankers at Citigroup or consultants at McKinsey. Conversely, there are dozens of Pakistanis who are doing well professionally as bankers, engineers, and consultants in New York and London, but the only ones being considered for the cabinet are ones who have politicians in their families.

We still have an establishment, but we no longer have to suffer their fools. We appear to have made enough progress to be getting the better credentialed among our ruling elite to rule us. Will that make a difference? Let’s find out.