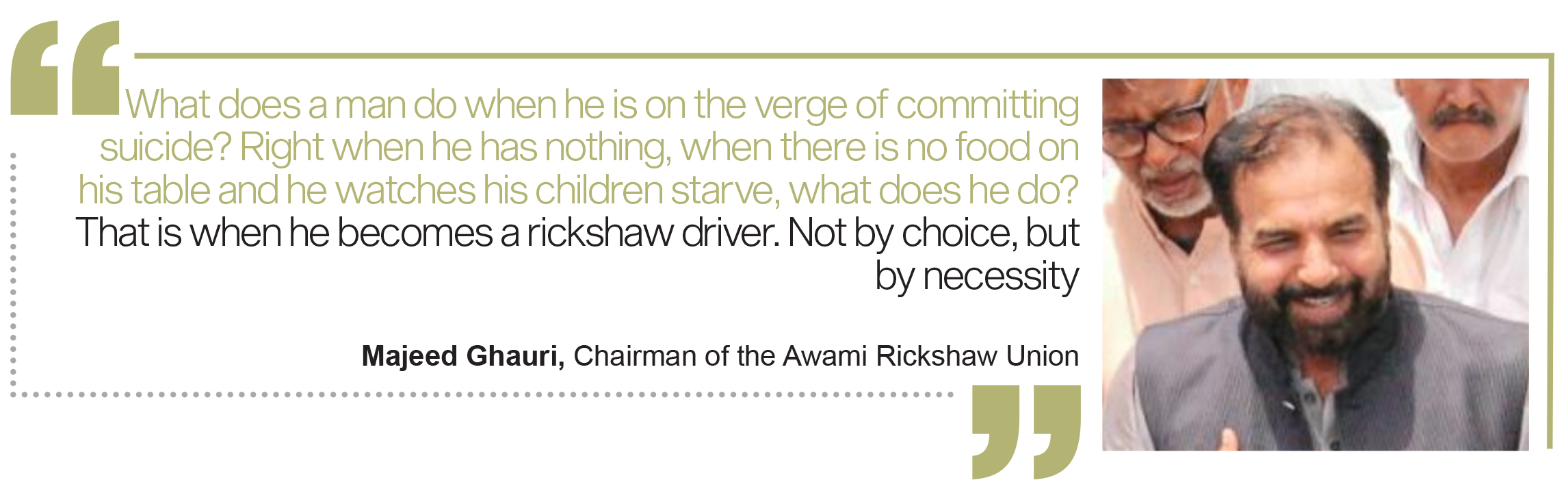

“What does a man do when he is on the verge of committing suicide? Right when he has nothing, when there is no food on his table and he watches his children starve, what does he do? That is when he becomes a rickshaw driver. Not by choice, but by necessity,” says Majeed Ghauri. As chairman of the Awami Rickshaw Union, day in and day out he hears the trials and tribulations of rickshaw drivers. These are his people, and they give him his mandate.

The centre of this world of rickshaw drivers is Lytton road. And this is where the battle for the future of the rickshaw is being waged. Where a small group of companies are trying to electrify Pakistan’s three-wheeler market, and convince the rickshaw driving population that they should swap in their regular petrol and CNG rickshaws for ones with electric batteries. And they are getting closer.

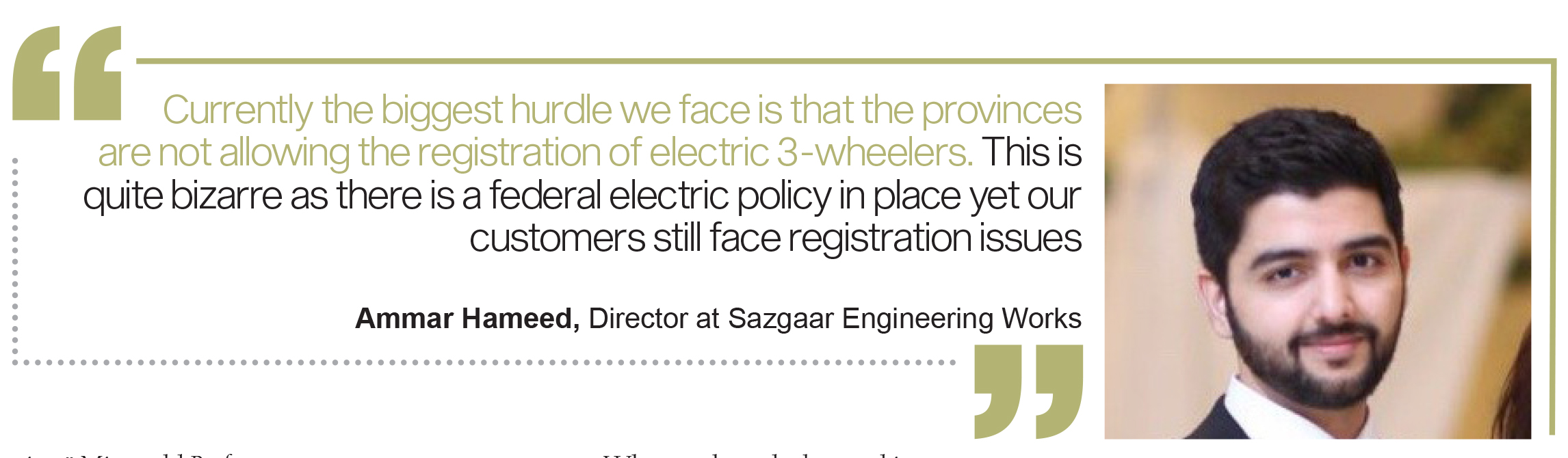

The Punjab Excise Taxation & Narcotics Control Department has moved a summary to amend the Motor Vehicle Ordinance (1965) and Motor Vehicle Rule (1969) to allow the registration of electric rickshaws, but it has still not been passed. The summary was approved by the Punjab Cabinet this month, and awaits a debate by the Assembly before it can be approved. It remains an agenda item every time the Assembly does meet, and the closer Pakistan does come to achieving some semblance of political stability, the closer we get to the summary being approved. That said, if the Punjab Assembly comes around to it, electric rickshaw registration could be a done deal any day.

The only question is, will the rickshaw drivers bite?

The rickshaw equation

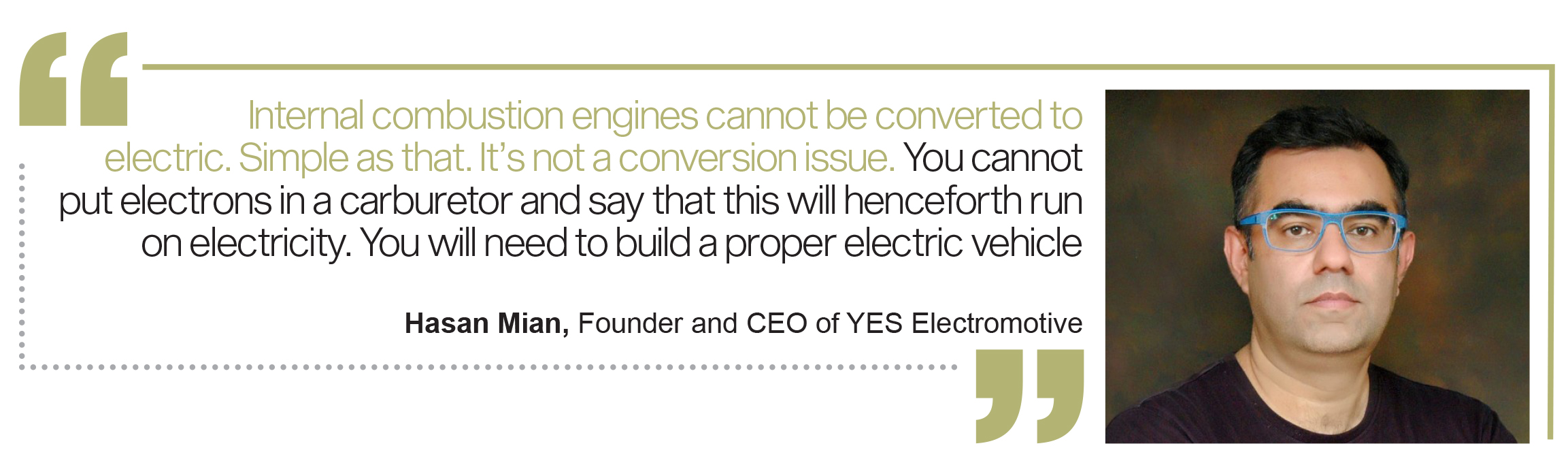

There are close to one million three- wheelers manufactured by over 45 automobile manufacturers in Pakistan, and electric rickshaws provide an opportunity to reset the entire market. “Internal combustion engines cannot be converted to electric. Simple as that. It’s not a conversion issue. You cannot put electrons in a carburetor and say that this will henceforth run on electricity. You will need to build a proper electric vehicle.” Hasan Mian, Founder and CEO of YES Electromotive, told Profit.

This is where many of these 45 companies have picked up on the scent of opportunity. Rickshaw drivers want more economically feasible vehicles. We saw that with the introduction of CNG rickshaws back in 2005-07, which have by now almost entirely replaced petrol rickshaws. Running these vehicles on. And the demand for cheaper transport and cheaper running costs is only going to increase with rising inflation. The first of these companies to have their electric rickshaw takeoff will reset the clock, and become the hegemon. But the question is, will these rickshaws be cheaper?

The affordability question

If you were to go out and buy one today, an electric rickshaw is at the very least two to three times more expensive than its conventional counterpart. So what are some of the available options?

Firstly, Profit took Sazgaar’s electric rickshaw as the basis for comparison. This is because it is the most widely available commercial three wheeler on the market. The electric rickshaw comes in three different models: base, mid tier, and high tier. These retail for Rs 720,000, Rs 825,000, and Rs 925,000 respectively. How much more expensive are they in comparison to their combustible engine counterparts? Based on our market research, Profit found that the average petrol rickshaw in comparison retails for roughly Rs 275,000.

However, for a fair comparison we utilised Sazgaar’s Deluxe and Royal Deluxe rickshaws. These two retail for Rs 315,000 and Rs Rs 344,800 respectively. Averaging out everything to account for different possible purchase combinations, the average electric Sazgaar retails for Rs 493,433 more than its combustible counterpart. This amounts to a 166% premium.

That is problematic, very problematic actually. Rickshaw drivers constitute perhaps one of the most, if not the most, price-sensitive segments in the automotive industry. You know what’s more problematic? This is where the battle between idealism and reality first takes place.

“Unless there is an outright ban on petrol rickshaws, I do not think electric rickshaws will be successful. 10-15% of drivers will switch. At max you will see 20% of them switch.” Ghauri told Profit. In contrast, Mian told Profit that “Electrification makes perfectly good sense from an economic and environmental point of view”. How do we reconcile these two juxtaposing points of view? Cost is the lowest common denominator between both arguments so let’s start from there.

“A regular rickshaw consumes Rs 1,500 per day, that is Rs 45,000 a month, and Rs 500,000 annually. It is a vehicle that you buy for Rs 350,000 which gives a bill exceeding the price of the vehicle itself in just 10 months after purchasing it. Electric rickshaws in contrast have the potential to bring down the cost to 20% of that.” Mian told Profit. This and its comparables are the linchpin of the argument that electric rickshaws make to prove their superiority over their combustible engine counterparts. This is also the first thing that Profit will look to put to the test to see whether these electric rickshaws can take off or not.

Do electric rickshaws work out to be cheaper?

So, are electric rickshaws cheaper? We already have our answer for the short-term in terms of up-front costs, so let’s look at how they fare in the long-run before we get back to this.

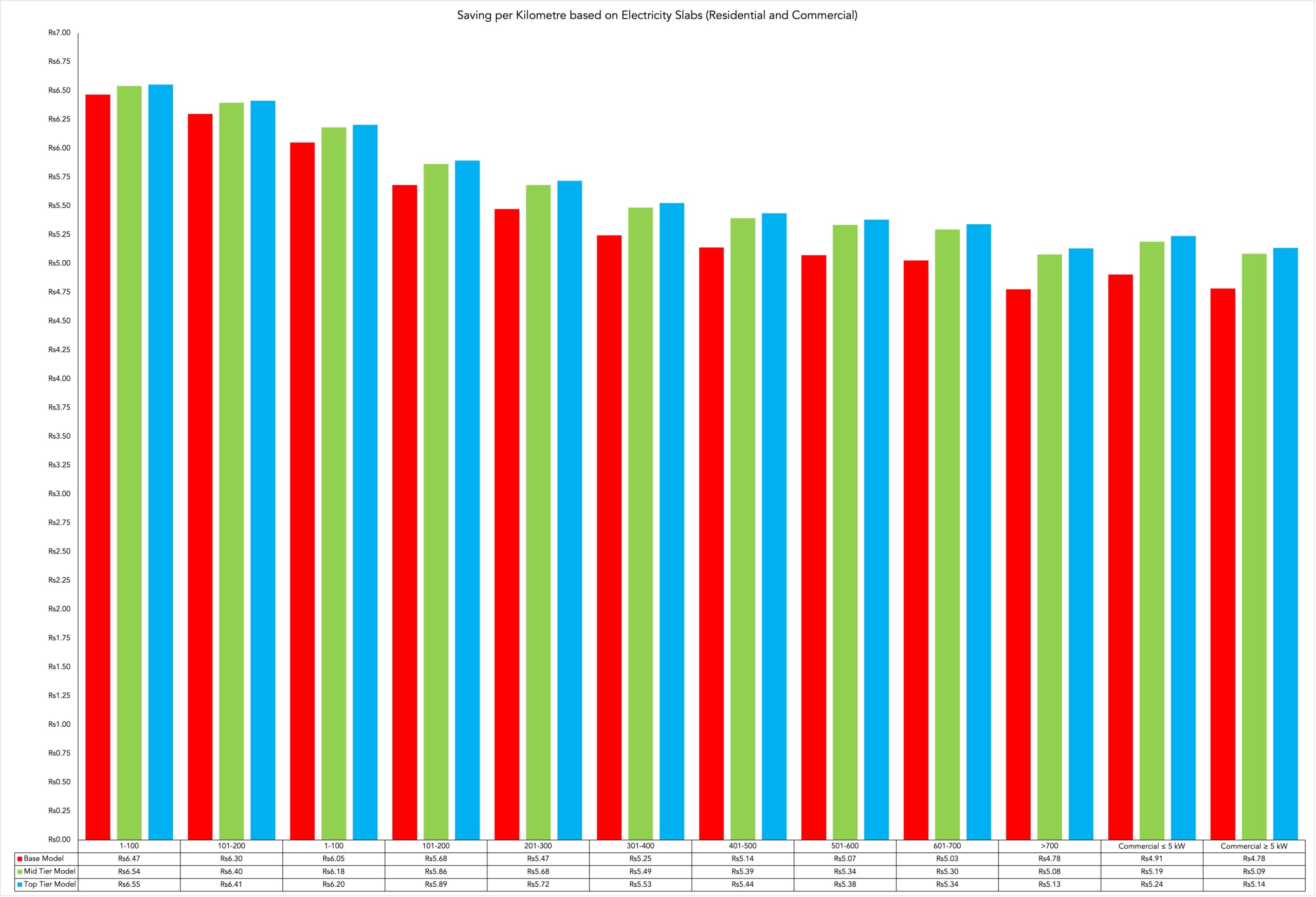

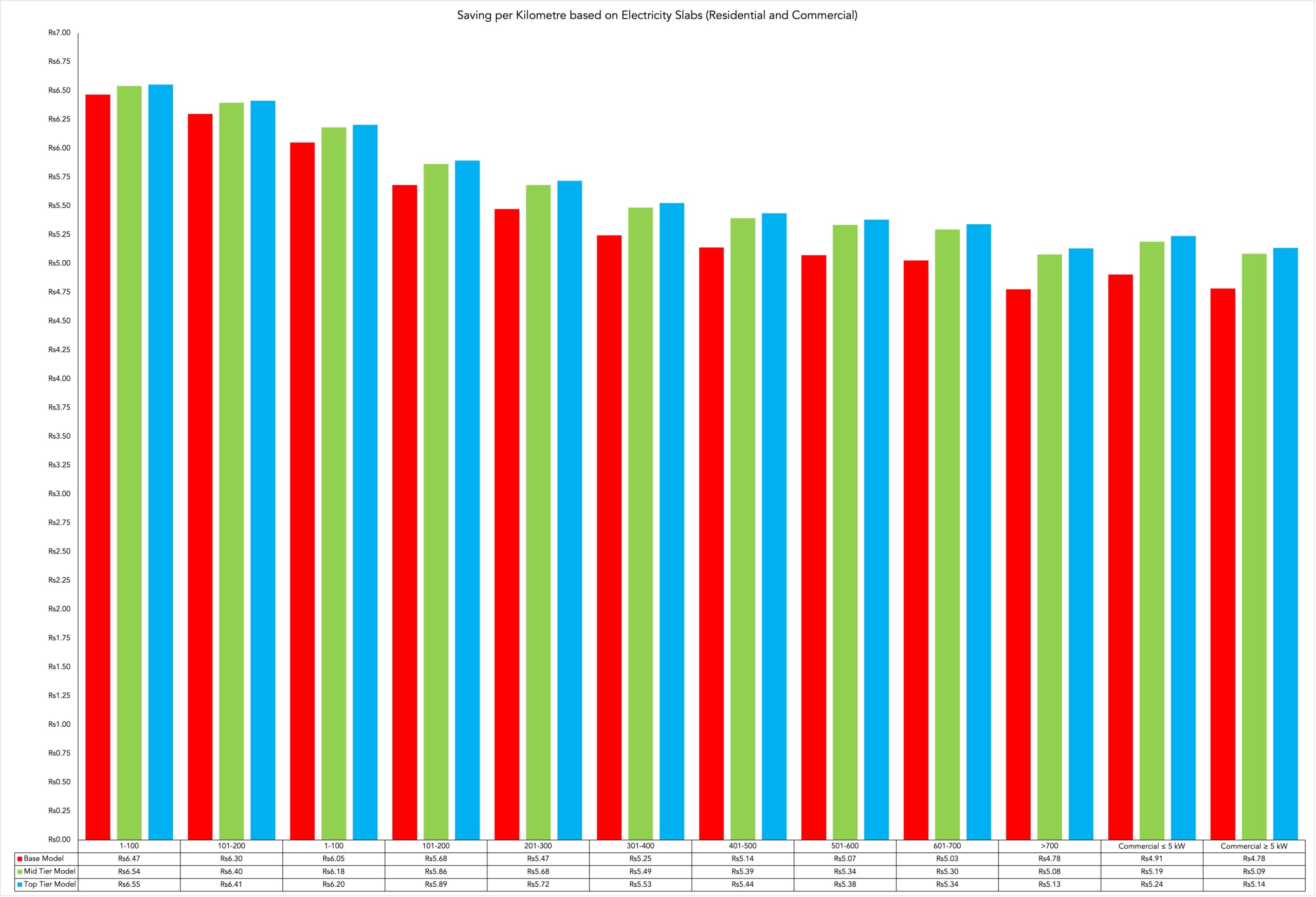

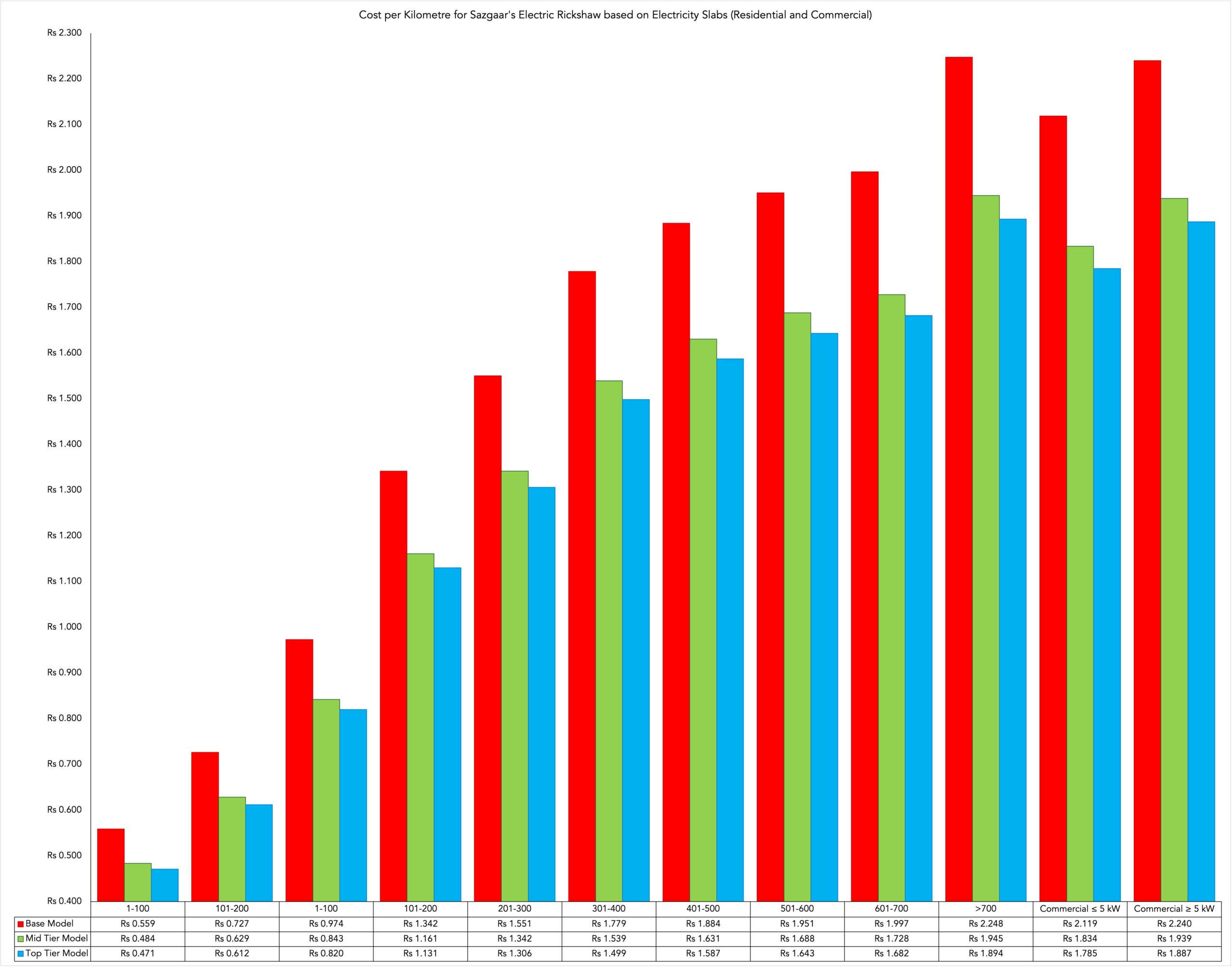

The aforementioned Deluxe Mini Cab and Royal Deluxe may vary in terms of engine displacement but they both have an average of 32 kilometre per litre of petrol consumed. Utilising a price of Rs 224.8 per litre for petrol, they incur a cost Rs 7.025 per kilometre. Now onto our electric contestants.

Methodology (feel free to skip):

Profit sought to find the cost per kilometre as well for the electric contestants to make the comparison fair. Here Profit took the tariff rates provided by the Islamabad Electric Supply Company (IESCO). Why IESCO in particular? They just had the easiest navigable website. Take cues Lahore Electric Supply Company (LESCO), please.

Profit then looked at the rates for all residential and commercial units available. Here it is important to note that electricity tariffs in Pakistan work on a slab basis. What does that mean? That means the tariff levied on you, in your bill, for a unit of electricity consumed depends upon the slab you fall in. The slab that a customer falls in depends upon the overall units of electricity consumed. The more units of electricity you consume, the more you will be charged per unit, and vice versa.

Profit utilised all residential and commercial rates to account for all use-case scenarios. Interesting tidbit about which slab users are actually using electric rickshaws later on.

Profit multiplied the Rs kWh (the cost of a unit of electricity consumed) for all slabs with the total battery capacity for all three of the electric variants. The battery capacities that were multiplied were also adjusted for inefficiencies that occur in transmission between the charger, battery, and discharging. Profit accounted for 10% inefficiency recommended by Zubair Khaliq, Director and CEO Multiline Engineering. This allowed us to find the total cost of charging the batteries of the rickshaws from 0-100. We then divided the cost by the total range the batteries could provide to find the cost per kilometre. What were Profit’s findings?

Verdict (don’t skip):

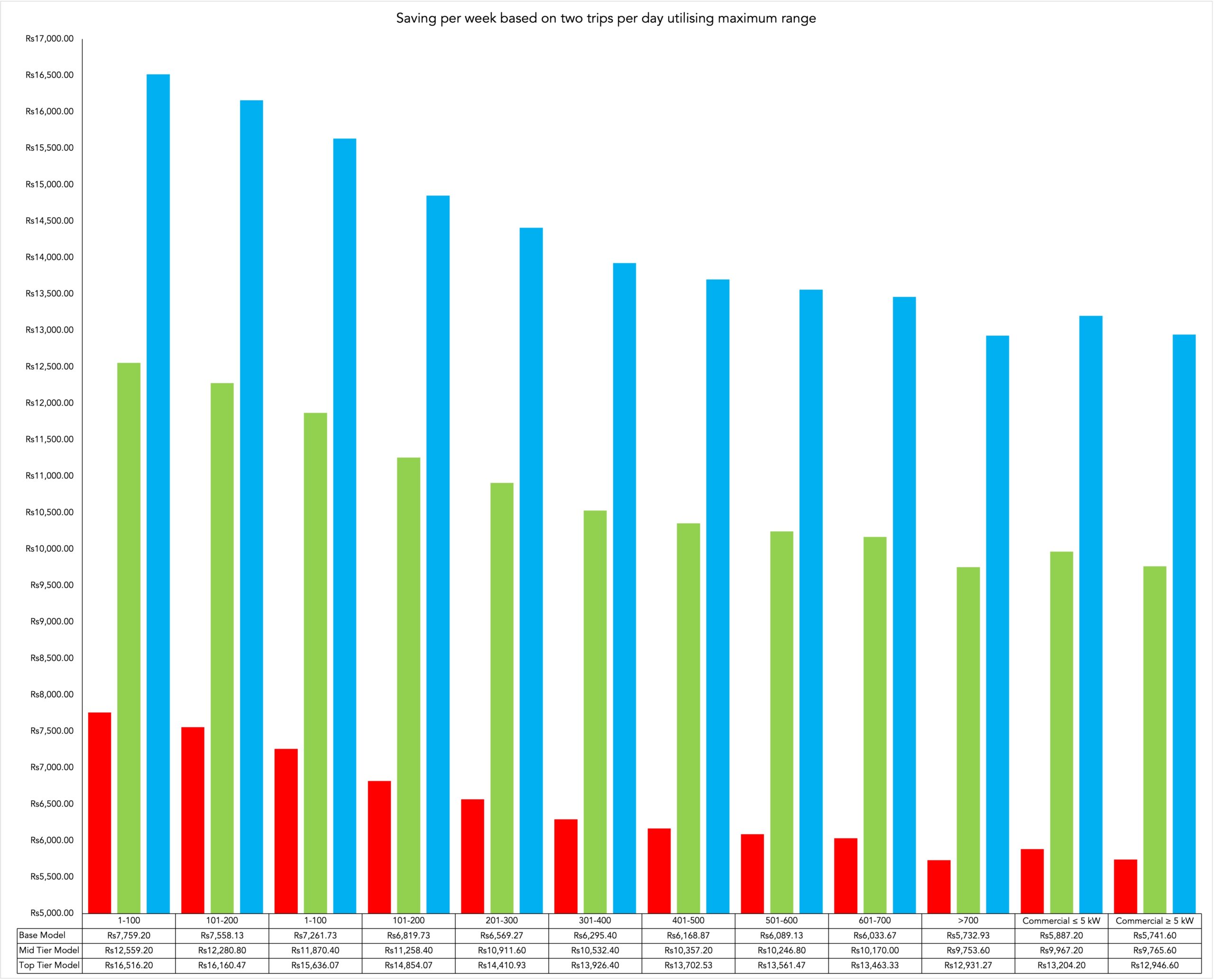

Electric rickshaws were cheaper than their conventional combustion engine counterparts irrespective of the tariff slab. How much cheaper? At minimum the rickshaw driver would reduce his fuel cost per kilometre by 68.01% or Rs 4.8 per kilometre travelled, and at maximum the rickshaw driver would save 93.3% or Rs 6.55 per kilometre travelled. How much does this translate into when running the rickshaw day to day?

The base model has a charging time of 4 hours and covers a total distance of 100 kilometres on a full charge. The mid and top tier models both have charging times 5 hours and cover 160 kilometres and 210 kilometres on a full charge respectively. Given the charging times, Profit assumed that each variant could be used for two trips a day, utilising the complete range of the batteries for each trip, given the total 8 and 10 hours needed to charge them twice. Profit found that given these assumptions, the rickshaws at minimum would save Rs5,733 per week and at maximum could also provide Rs16,516 worth of savings if used instead of their combustible engine counterparts.

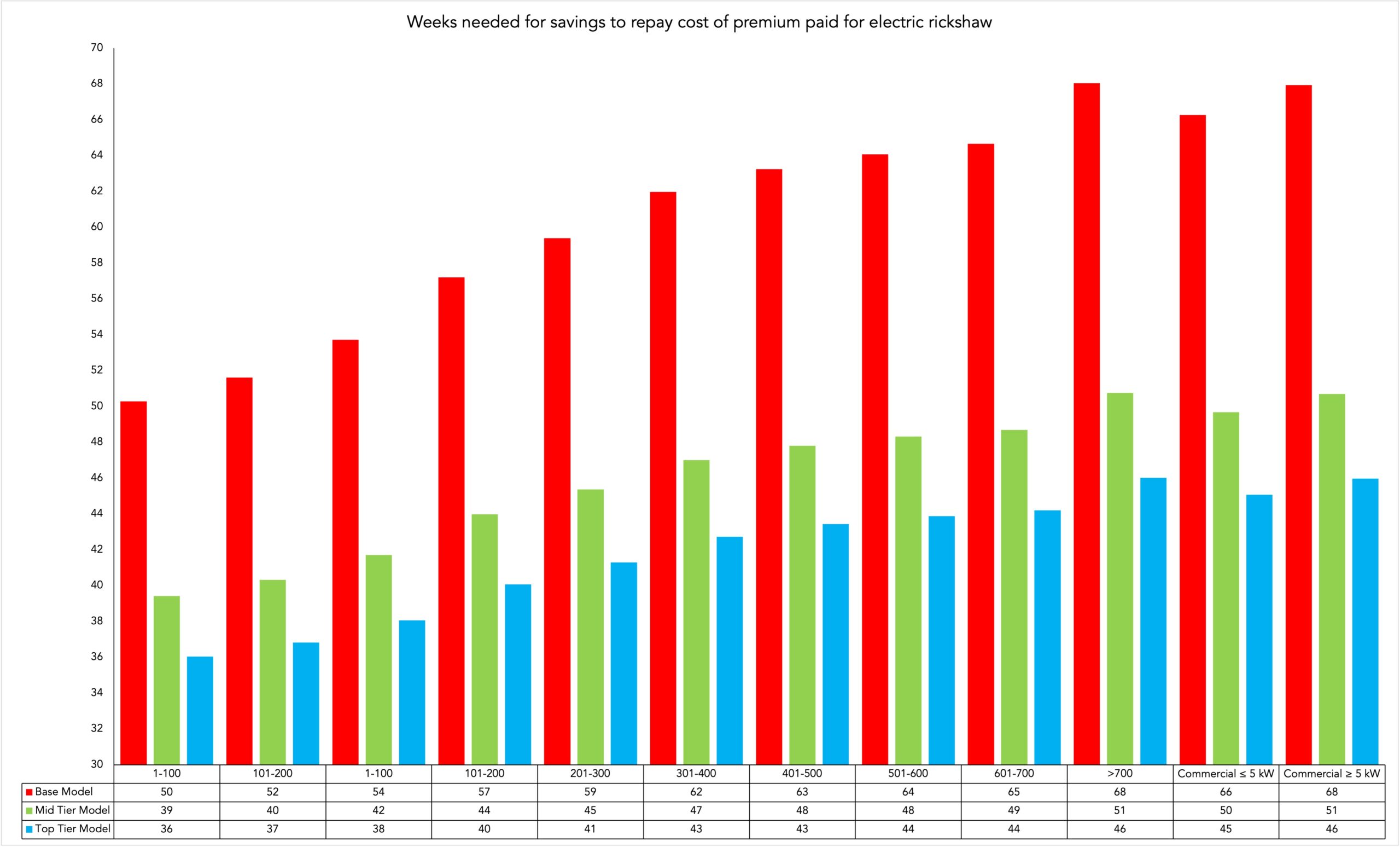

Finally, Profit sought to identify the payback period the rickshaw driver would have to meet in order to pay-off the premium associated with their more expensive rickshaw based solely on the savings from switching to electricity from petrol. This calculation was in line with Profit’s assumptions that the electric rickshaw would be driven twice a day. Furthermore, we assumed that it would be utilised for six days a week. Why six? Irrespective of whether it was used directly by the driver or leased out, we took the liberty to assume that the owner of the rickshaw, not the driver, would not want to be associated with it for all seven days of the week.

In identifying the premium, we averaged the prices of Deluxe and Royal Deluxe. We did this because we wanted to account for the chances of the buyer opting for either of the two variants. The average price worked out to be Rs 329,900 between the two models. This average price was then subtracted from each individual electric rickshaw to identify the premium that would sought to be recouped via the savings.

Profit found that the earliest the buyer could payback this amount was 36 weeks whilst the latest would be 68 weeks. Beyond the requisite time period, the savings will then magnify the profits the owner will enjoy. How much? We do not know because Profit did look into the fare cost charged to passengers per kilometre driven as there is no such fixed amount across Pakistan. So, all good then? Not really.

Firstly, everything centres around rickshaw drivers saving additional expenses they would have otherwise incurred by switching to electric. However, that is largely it. There is no guarantee that rickshaw drivers will be able to charge higher fares to their passengers for the utility of riding this newer and fancier rickshaw simply due to the nature of the market they put in. Subsequently, the entire sales pitch to rickshaw drivers is then that they can enjoy lower operating costs in exchange for a one time higher upfront cost.

“This is a unique economic entity which makes you poor and keeps you poor as an individual and as a society. It bleeds income. Having a low upfront cost, you have basically acquired a ball and a chain.” Mian tells Profit. The question then is, will they bite?

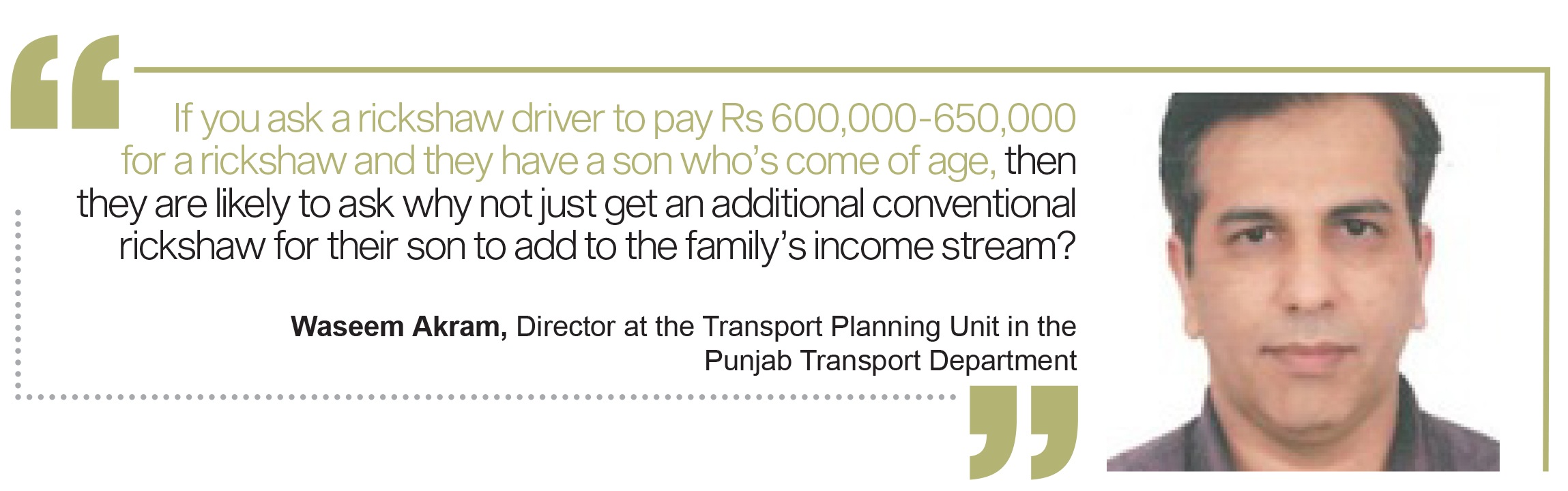

“If you ask a rickshaw driver to pay Rs 600,000-650,000 for a rickshaw and they have a son who’s come of age, then they are likely to ask why not just get an additional conventional rickshaw for their son to add to the family’s income stream?” Waseem Akram, Director at the Transport Planning Unit in the Punjab Transport Department, told Profit. These are valid reservations. What about the savings from the cost of operations? Well, these might be very hard to explain to customers. If for nothing else, because rickshaw drivers have alternatives to electric already.

“LPG rickshaws have the same benefit, electric rickshaws are not novel in any way. Their only benefit is that they reduce pollution, and so they’d help us in getting rid of smog. You can have a conventional rickshaw fitted with an LPG kit for Rs 15,000-20,000 and you would save significantly more money.” Ghauri told Profit. “The only downside is that the LPG cylinders are hazardous. If the Government could give us access to OGRA (Oil & Gas Regulatory Authority) certified cylinders then that would be a better alternative to electric rickshaws altogether.” Ghauri continued.

It is very clear that irrespective of the additional cost savings, rickshaw drivers either lack the means to fork out the capital needed to purchase these expensive vehicles or already have other things they would rather allocate the same amount of money on. However, it’s not like companies are not cognisant of this. “In our society where you have high interest rates and there is a lack of abundant cheap financing. The two and three wheel market is not served by banks, it is served by informal finance with very high interest rates. When you have a high upfront cost and lower operational costs then spreading the cost over an easy instalment plan would allow us to overcome a key hurdle in electrification.” Mian told Profit.

So, where are our banks? The modern banking system’s raison d’être after all is to bridge financing gaps. One can even ask why rickshaws aren’t incorporated into existing car financing schemes. Profit even confirmed with Muhammad Iftikhar Javed, Business Head of Secured Lending at Bank Alfalah, that a repayment schedule for a three-wheeler loan, if it did exist, would be “100% identical” to that of a car financing loan.

However, there is a good reason as to why most of us have never seen a bank advertise rickshaw financing schemes in any form of media.

Bridging the financial gap

Okay to start off. Banks are not big on this for a myriad of reasons. “The banks don’t get involved in 3-wheel financing as they deem it too risky. However, the opportunity is there for banks to step in and take a big chunk of the market.” Hameed told Profit. So, are there no lenders at all to reduce the cost of buying a vehicle at all? Profit asked Hameed about the matter to which he responded that “The three wheel finance market is currently run by individual investors and dealers.”

Who are these dealers and investors that operate in the absence of banks? Your local Joe’s to be honest. They can be your friends, family, affluent neighbours, or just your local loan shark. There is no set definition or archetype for who these lenders are because they all operate in the informal sector. The only commonality is that they charge higher interest rates than banks, but they also cater to the rickshaw drivers in manners that banks cannot.

“They deal with them based on their specific requirements, they handle the courts and police stations, and they resort to phenti when required to recover the rickshaw.” Javed told Profit. “All of this is not possible for banks to do.” Javed continued. Assuming banks were to get in on this, there are still many problems that would need to be addressed.

“Rickshaw buyers are generally going to be uncomfortable with the documentation banks require. Most people are unable to meet the terms and conditions for having a car financed, how will they (banks) convince rickshaw buyers to sign up? How will rickshaw buyers produce guarantors for their loans?” Akram told Profit. Again these reservations are completely understandable. “Buyers in this segment are unlikely to have very established businesses. In the cases that they do, those businesses are unlikely to be properly documented. This will create repayment challenges.” Javed echoed similarly to Profit.

Irrespective of this, rickshaw companies will likely have to convince the banks in some way to entice them. Why, you ask? It goes back to the higher cost of informal financing. “If we assume that banks provide any product to you today at a cost of 18%. The same thing if your friend, neighbour, or anyone in the informal sector provided you, then they would provide you the option to have split over six instalments. However, when they do it, the cost will shoot through the roof.” Mian told Profit. Is there a practical example of this that would help everyone understand things better? Ghauri explained to Profit how a typical rickshaw buyer goes about financing their purchase, “Family members will lend you Rs 50,000-60,000 to help you out, and when you go to a dealer then they will provide you with the opportunity to split the remaining Rs 70,000 over a few instalments. People end up pooling finances like this and happily buy rickshaws, however, they end up paying Rs 400,000 or so for something that originally cost them Rs 250,000.”

The informal sector provides our electric rickshaw companies with a unique problem. “What will someone buy when they have expensive instalments? Whatever is cheaper upfront. Whenever something has a higher initial cost, you need formal financial institutions to get into the game to spur sales.” Mian told Profit. So, whether they like it or not, electric rickshaw will somehow have to woo the banks.

However, let us assume that somehow all of this does manifest and we have rickshaw buyers signed up to purchase the fancy electric rickshaws through a bank. Will it work then? “You will only have 25% of rickshaw drivers meet any repayment obligation. No rickshaw driver will fulfil the repayment obligations after the second or third payment. You will eventually have a political leader forgive the debt taken on by rickshaw drivers, leaving the banks in ruin. Ghauri told Profit. “At best you will have 50,000-70,000 rickshaws on the road through any financing scheme” Ghauri continued.

So we have our answer. However, herein lies the solution as well. Utilising a conventional to finance rickshaws is not just a bad business decision but it would also be unfair to do so. “It would be unjust to the rickshaw driver if you were to attempt this sort of financing at today’s cost of 21%” Javed told Profit.

What if we tried something bespoke for all of this? This would not be entirely uncharted territory for banks after all. “Banks lent billions of rupees in the previous 3-4 years for low-cost housing. This was a very high risk segment for 3-5 marla houses. However, with that the banks were satisfied with the credit guarantees provided by the Government of Pakistan, State Bank of Pakistan, and the Pakistan Mortgage Refinance Company.” Javid explained to Profit. “This would not be a normal product. It would be a special product that would need to be operated on a project basis with the Government and State Bank of Pakistan being directly involved for it to work.” Javed continued.

Let’s do a recap now. What have we learnt? Banks don’t serve the rickshaw market because they don’t want to be caught in the quagmire. In their absence, the informal sector serves the market but charges very high interest rates. Large repayment amounts incentivise buyers to only go for those products that have smaller upfront costs. However, can banks do it? Yes, they have done something similar. The only thing is that they need Governmental level guarantees and support to do so. Is the Government interested in this? Yes. Perhaps someone just needs to perform the matchmaking role between the Government and the requisite entities needed for the space to take off?

It seems we don’t have lift-off

So, where are we at now? Well, ceteris paribus, electric rickshaws are not going to take off at their current retail prices. Changes will be needed in the external environment to get this off the ground. The companies,thankfully, are cognisant of this as well. What are they doing apart from potentially wooing the State and financial institutions? Well, they are trying to devise creative business plans. Let’s run through a few that Profit found when researching for the piece.

“We are planning on launching a battery swapping model in which the driver does not own the battery and instead he rents it out. Once the battery is dead they can head over to the nearest battery station and replace their battery in a matter of seconds. This will help with the overall cost of the vehicle as the battery motor and controller are the costliest items. More importantly the driver will not have to wait for their vehicle to charge.” Hameed told Profit.

Elsewhere, Mian told Profit that, “Selling to individuals is problematic so we have lined up fleet operators in Lahore and Karachi to whom we will roll out our product.”

Perhaps the note to end this is a tidbit that Profit found when researching for this piece. This is also why we looked at all electricity slabs and not just the lowest. When talking to the sales team for an electric rickshaw, Profit inquired with them about the current set of customers, and if any customer would be willing to be interviewed. Profit was humorously surprised at the response, “Sir, it will be hard for us to put you in contact with them. Most of the non-corporate customers (they only mentioned two companies) are very wealthy individuals who value their privacy.” When Profit inquired why such wealthy individuals were buying rickshaw of all things, we were told that “They have just bought the rickshaws to have their domestic staff fetch their groceries because of the novelty the rickshaw provided.”

very good technology for common man to facilitate

I have read so many content about the blogger lovers however this article is truly a nice paragraph, keep it up.

온라인 카지노

j9korea.com/