It begins with a fetishisation of meritocracy. Ask a person for their background and they will delve into an origin story. For a select few, that origin story will be steeped in privilege. There will be tales of land-owning great-grandfathers and enterprising grandfathers that used the wealth from that land to set-up industries.

But for many others, the story will be very different. They will involve recollections of difficult times, of working-class struggle, and of upward social mobility grounded in hard-work and ability. For a few of the people telling these stories, it will be true. And for a lot more, they will be an exaggeration.

Most people have a strange relationship with their own privilege. The only time someone is happily inclined towards accepting the advantages that their birth afforded them is because the privilege comes with a sense of grandiosity. But for most people that grew up upper and upper-middle class, acknowledging their status is a hard pill to swallow. The average person that gets an education, gets a degree, and builds a career by working their way up in a profession like to think that they got theirs as a result of their hard work and because they deserved it.

The reality is rarely so simple.

A 2013 study published in the American Sociological Review found what it christened the ‘’grandparents effect’ — a phenomenon that showed that a child would be two and a half times more likely to find themselves in a professional-managerial role if just one of their grandparents had held a similar job in their career. Similarly, a report published in The Guardian last year based on a survey of nearly 200 professionals found that people “”tend to downplay their own fairly privileged upbringings and instead frame their lives as upwards struggle against the odds deflecting attention away from the structural privileges these individuals enjoy.”

Why would people shy away from their backgrounds? Largely because they want to portray the outcome of their lives as “more worthy, more deserving and more meritorious”. It is a natural if lopsided desire, and one that can be seen quite clearly in Pakistan, where the term ‘middle-class upbringing’ is thrown around casually and with great confidence. This, of course, gives rise to the question, what does ‘middle-class’ mean in Pakistan?

There are more than a few ways to answer that question, and depending on who you ask the conclusion you reach will be different too. Declared annual incomes, for example, can give a fairly good picture of how the populace of Pakistan can be classified according to their incomes. But then there are also certain global measures of class that come into the picture. Besides, is the picture painted solely by incomes a good metric of classifying people? And who defines what those income levels are? It is worth taking a closer look at what the term ‘middle-class’ means in Pakistan in conversation and in numbers. And there isn’t a better point to begin talking about it than with the term itself.

What does middle-class mean?

In terms of wealth and income, one would think that figuring out where ‘middle-class’ falls would simply be a question of calculating the middle point between the richest and poorest person in a country. Except this is not how it works anywhere. According to different economists, determining what ‘class’ a person belongs to can be based on income, wealth, consumption, demographics, and even aspirations.

That is because the concept of ‘class’ itself is a confusing one. According to Dr. Durr-e-Nayab of the Pakistan Institute for Developmental Economics (PIDE), “the concept of class can be traced back to Karl Marx with his classification based on the relationship to the means of production.”. What that means is that someone’s class is judged better in terms of their relation with the means to produce wealth. Do they own or control the means? These are the CEOs, Landlords, and people in power. Are they the labor for the means? These are the lower classes. Or are they at the intersection of the two mentioned above, namely the different types of middle class.

You could be earning Rs. 50,000 as a 16th grade government officer in a ministry, and your social connections and access to power alone would be enough to take you out of the middle class. Meanwhile, the same 50,000 will never render a similar privilege to, say, a self-employed electrician. And that is where the complexity lies in many ways, what determines your class? Is it cash, credentials, or culture?

Figuring out class is a complex exercise. The idea of using income alone, to classify people, doesn’t always go hand in hand with other measures of wellness like wealth, asset ownership, type of employment and all the other social denominators.

And in Pakistan, it is even murkier than usual. Even if we simply decided to take income as a measure to ascertain the middle class, there is the problem that the richest in any part of the world have far too much income (hidden or declared) to be put on a homogeneous, unskewed normal distribution of incomes. Simply put, the rich might be richer than they proclaim (duh!) and the seemingly poor might not exactly be the posterchilds of transparency.

Let’s talk about income

Whenever there is a conversation regarding class, it often dissolves into vague claims about what car a person drives, where they live, and where they went to school. While these are indicators of where you stand financially, they are not all-encompassing answers. People with solidly middle-class incomes may have assets that increase in value over time. They may, for example, sell some part of a small inheritance to pay for their child to go to a big university or for their wedding. The existence of assets skews the data terribly, which is why determining a person’s membership of the ‘middle-class’ is difficult.

For the time being, and to simplify our search for the Pakistani middle-class, let us go the simplest possible route and look at what the middle-class would look like based entirely on income. Essentially, more than figuring out the ‘middle-class’ this will give us an idea of what Pakistan’s middle-income group looks like.

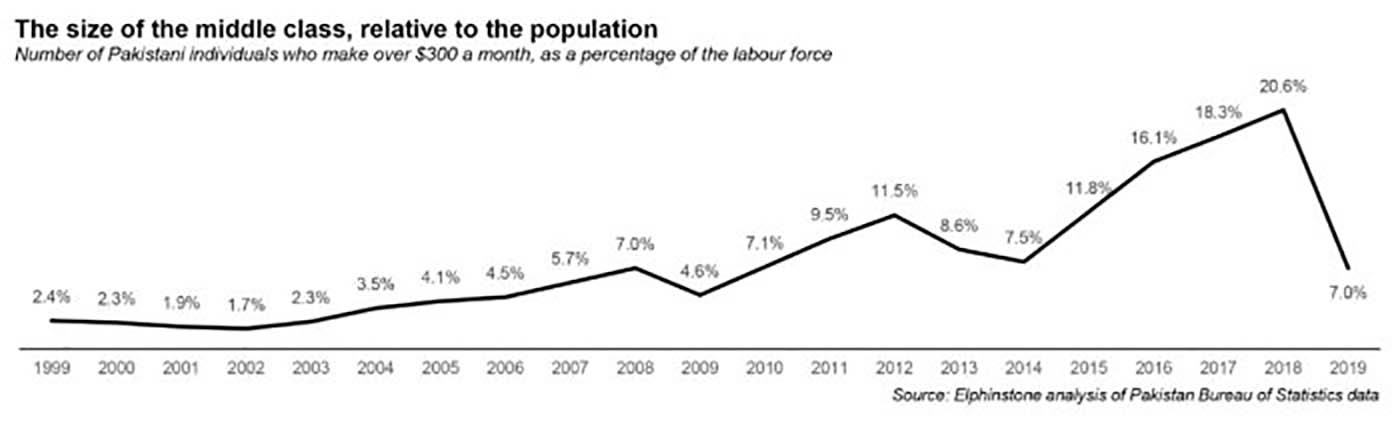

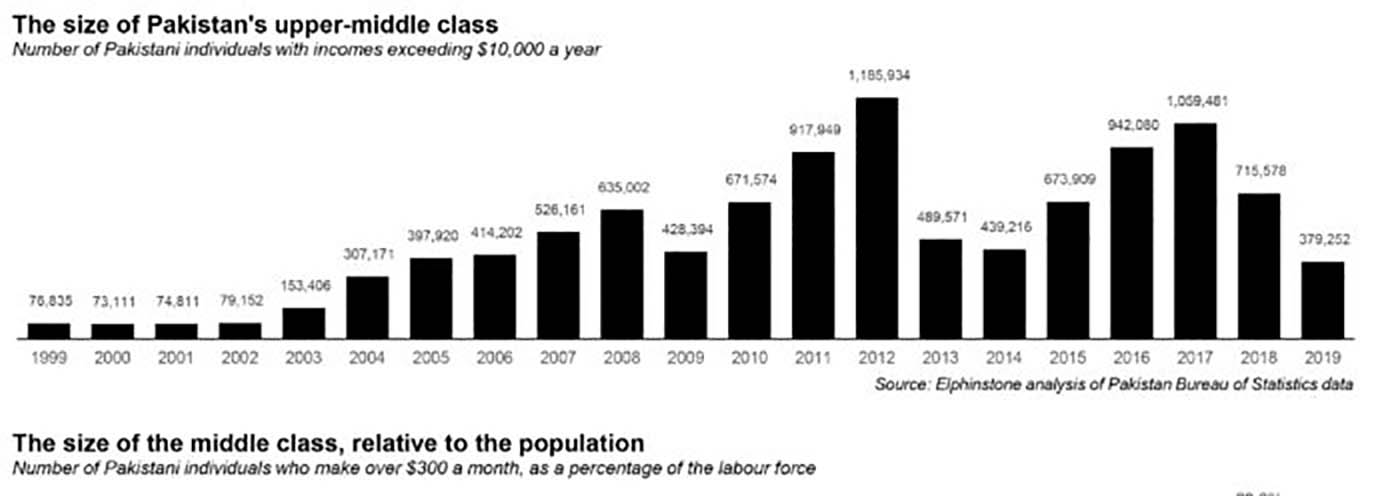

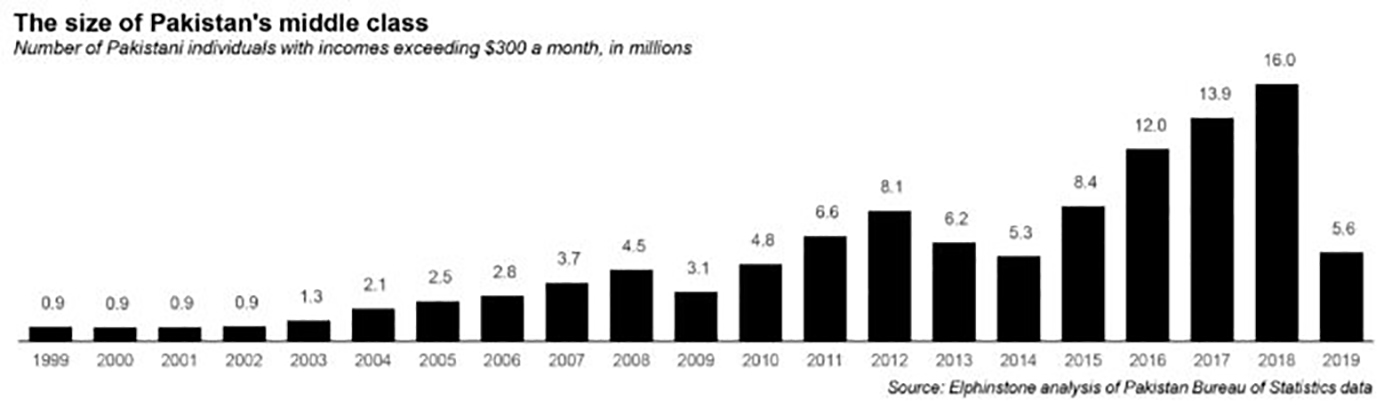

The world bank states that a person earning between $10 to $40 in a day is “middle class” in a lower-middle income country like Pakistan. This adds up to about $300- $1200 a month. As per today’s exchange rate, that value is somewhere between Rs. 65,000 to 266,000. When June 2019 started, the same world bank definition meant an income range of Rs. 44,000-176,000.

(Note: We use the exchange rates from June 2019, because that is when the calculations of the HIES survey were made. This sets June 2019 as the vantage point/base year and also surpasses any disparity caused by exchange rate volatility in the recent times)

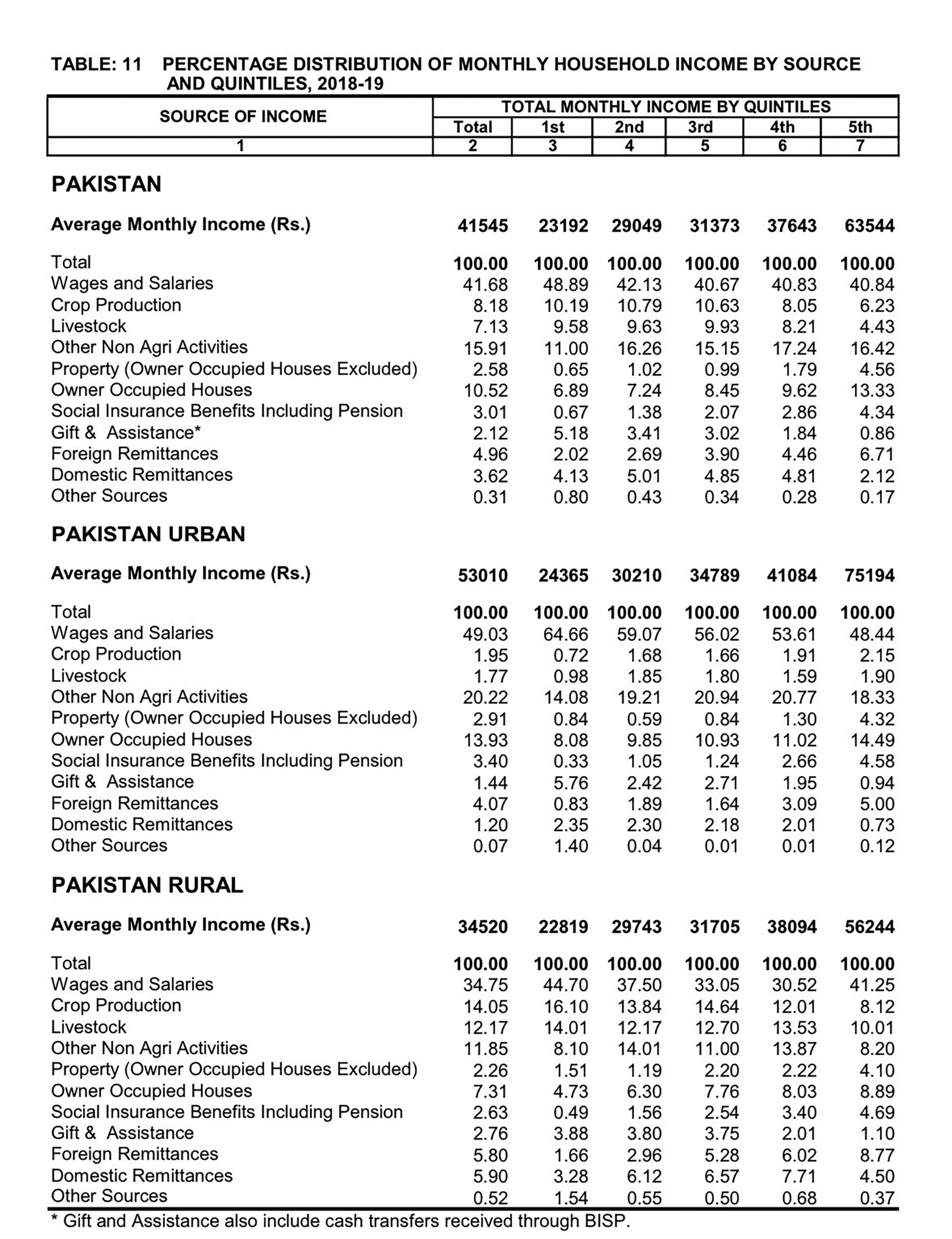

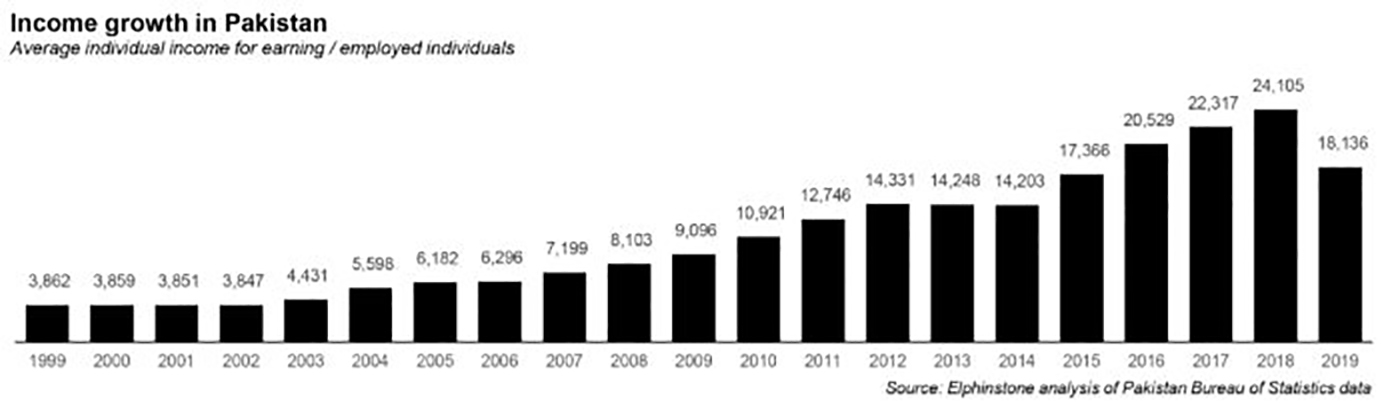

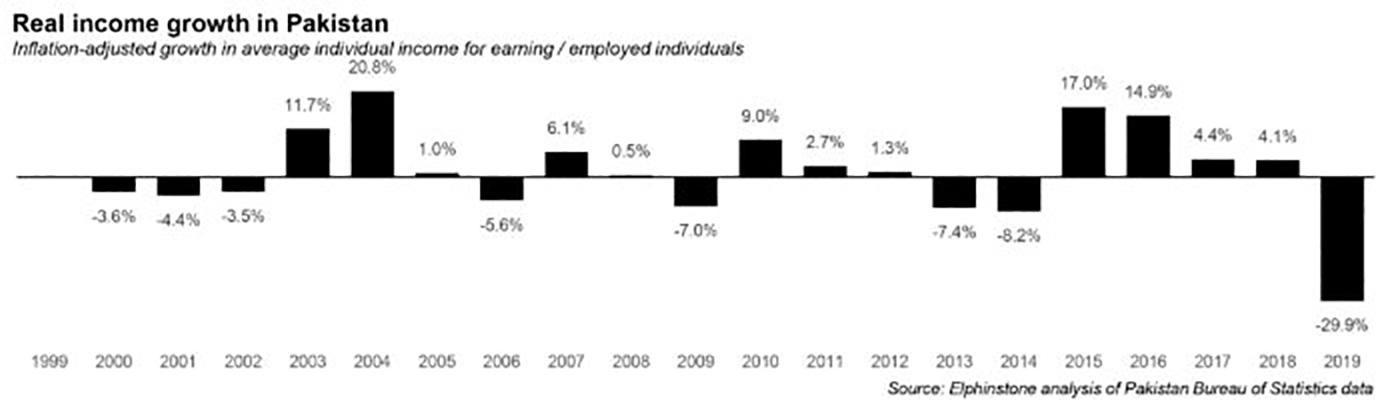

But that World Bank definition doesn’t at all reconcile with the distribution as portrayed by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. According to the Household Integrated Economic Survey (HIES) 2018-19, by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, the average household income, by June 2019, was Rs. 41,545. This is the total income of Mr. X’s house, a mere 41,000, provided that the number of people living in that house is 6 or 7 (Average household size is 6.24). Interestingly, the same data states that the average household incomes of the 5th and 4th quintile as Rs. 63,544 and Rs. 37,533 respectively. That means that the richest 20% earn only Rs. 63,544 and the next 20% after them earn Rs. 37,533, on average.

What does this mean for Mr. X? This means that Mr. X is actually among the top 30% of Pakistanis with respect to income. Then how is Mr. X “middle” class? If the world bank definition is to be considered true, then the majority of the richest 20% of Pakistan is actually “middle” class. Essentially, the question here is whether a person is middle-class relative to the rest of Pakistan’s population or on a more defined global scale.

Then there is also the issue of the PBS data, which comes into question. Like every other home-cooked thing in Islamabad, the PBS data should be taken with a pinch of salt. “The income data collected by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, is largely under-reported due to the very nature of the survey data collection”, says Dr Umair Javed, assistant professor at LUMS. Shockingly, it turns out that a lot of people, mostly in the highest quantile, when asked about how much they earn, don’t give the right answers. Dr Javed tells Profit that there is a consensus amongst the people who work with the income data that it is understated. The degree of this understatement can range from 30%, to as much as 100% for the upper quantiles. And the fact that we do not have reliable tax data, doesn’t help either.

So does that mean that we should resort to the definition set by the World Bank? We can, but in this case it is important to realize something. The World Bank blankets the Middle Income countries’ middle class under one group. A country with a gross national income (GNI) of $1200 has the same definition of middle class as a country with GNI of $3600. So while the lower bound for the middle class ,Rs. 44,000, may be relevant in Pakistan,the upper bound of Rs. 176,000 would be more relevant for a comparatively richer developing country, say Columbia or Turkey.

A former economist at the Planning Commission and a development sector expert, Dr. Muhammad Saleem told Profit that, these benchmarks are looked at better, in respect to the defined poverty line. As of 2018, 21.9% of Pakistan’s population is below the poverty line, according to the World Bank. This means that while a large number of Pakistanis are above the poverty line, the classification of their income is not happening amidst the incomes of 100% of the population, but among the 78%, who are at least earning a (questionable) living wage. This makes the pool of incomes narrower and is yet another way to consider the PBS data understated.

Meanwhile, columnist and Director of The Pakistan Initiative at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center, Uzair Younis, in a recent tweet also looked at income as a measure of figuring out what constitutes middle class income in Pakistan. “According to the 2018-19 HIES, the average income of a household in the top 20% was PKR 63,544 per month. The middle class (3rd quintile) makes PKR 31,373,” he says.

“One can argue that HIES data is off, and it probably is. But even if we double the third quintile’s income, we are looking at an income of ~65,000 a month for a middle class household and ~130,000 for a top 20% household. Now folks can judge themselves on where they stand.”

So if we consider the benchmark by the world bank and the PBS data together, the entirety of the first quintile is below the poverty line. In the remaining 80% people, We land at an estimated figure between Rs. 33,000-52,000 that can be reasonably deemed to be at the middle (Give or take Rs. 8,000 to account for some of the disparity in data and average deviation between the quintiles). If the PBS data is taken at the face value, the majority of the middle 40% of Pakistan (except the ones below the poverty line) will lie between the said income level. Bear in mind that this estimate is for the middle of 2019. But this is where it gets even trickier. What we just defined isn’t essentially a class, a better term for that could be “middle income group” as suggested by Dr. Javed. What, then, is class?

“Good income has nothing to do with class”

“It could be about something as little as your taste in music and your consumption preferences”, says Dr. Umair Javed on how to define classes. Subconsciously, everyone realizes that their access, their lifestyle, and their friends define as much of their socio-economic class as their income does.

It is a food chain of superiority in which income is the most important, yet not the only deciding factor. Having said that, someone higher up in the top quintile of income or simply the top 5-10% is in no way, or form defined as middle class. Even if they lack privilege, it is more of a conscious choice. By the virtue of their wealth, they would not be denied access to most of the aforementioned variables.

Another thing that tempers with our understanding of the middle class is not considering wellness, quality of life and wealth statistics. These variables drastically change our definitions of class and prestige, especially across rural and urban areas. Ownership of assets, oftentimes, does not translate into income. The infrastructural development in your dwelling also plays a huge role in the quality of your life. Even the difference in the incomes of the middle income groups, in both the rural and urban areas are statistically significant. “Developed countries, like the UK, have designed a much more efficient system that takes occupation into account when classifying people,” shared Dr. Javed.

So why do people ‘want to-be’ middle-class?

“The educated, urban segment does not want to associate itself with the exploitative elite. Because, in an unequal society like Pakistan, people who are aware of the inequality, don’t want to be perceived as the reason for that. The landed elite is however different from this, they take pride in being the flag bearers of inequality”, says Dr Javed. And this point goes to the heart of the issue, and back to where we began this story from.

A fetishisation of meritocracy. There are two kinds of people in upper-income groups. There are those with the ‘Chauhdry’ fascination. Who either are or want to appear a part of the landed gentry — families that take pride in being industrialists and zamindars for generations. Along with it comes a sense of history, of grandiosity, of belonging. There can be no greater stake than owning land.

And then there are the other kinds. People that have been socially mobile in the recent past. Whose parents, grandparents, or great-grandparents became a part of the upper classes by joining the managerial workforce. A few generations down the line, even though they are born and brought up in solidly upper-class circles and circumstances, they like to portray their lives as a rise through difficult circumstances based on their natural abilities and hardwork.

And in many ways, it is a relative question. A Lahori schoolboy from Beacon House, for example, who travels in a Corolla may look at his contemporaries from Aitchison College riding horses and driving around in Land Cruisers and feel that they are middle-class in comparison. However, perception alone does not make reality.

Educated or not, acquiring more wealth and aspiring to have a constantly better lifestyle is most people’s psychological orientation. How do we then get to “cancel” someone on twitter because they called themselves middle class? To solve this pressing issue, here are a few rules of thumb to check if you are as poor/rich as you think you are. If the average income in your household of 6 was above 70,000 in 2019, you were most likely in the top 15-20% of Pakistan. If you have made an unsponsored trip to the US, at any point in your life, you are not middle income or middle class. If your family has had ownership of a house in any reasonable urban dwelling, there is a high chance that you are not a middle income family. If you have good or even reasonable connections in the government/ police/ military etc., you are not middle class.

there is in-equality in economy. that is there is gap in Pakistan. there is gap between middle class and lower class

Good Information

Statistics can show an estimated picture of class sizes but for individuals and families basic functions of household are key to where one belongs.

If you or some members of your family do other people’s housework to get by you are lower class.

If you have lower class doing your household work then you are at least middle class. This can have an upper strata where you or anyone in your household never does any household work its upper middle class at least.

If you have all the trimmings of upper middle class but you and your family don’t have to work at all to even earn enough to fund your household then you are proper upper/rich class and sky is the limit.

Nice!

Second classification by one of our late friend who was a decorator for the middle and rich class.

He insisted on visiting the toilet.

No WC- Lower class

WC in an old style toilet – middle class

Full designed bathroom with matching WC – upper class

As it says, ‘life is stranger than fiction’. It is hard to understand the true dynamics of inherited success or hard worked success. And who deserves what…

Perhaps the world is designed like that, it may not be easy to understand easily.

We can only play the cards we are dealt with.

I have read so many content about the blogger lovers however this article is truly a nice paragraph, keep it up.

온라인 카지노

j9korea.com/

Pakistanis are secretely rich. mostly, they hide their income to avoid taxes i know many people having millions and even billions of rupees, but still living as middle class persons . They just drive middle class cars such as toyota carolla, honda city and some are even driving suzuki car just to pretend they are not rich.

I personally do belive that richness is directly proportional to freedom but pakistani society is very Conservative . Here everyone is ready to take life of person who do some little blasphemy . But focus of same people in economy is zero.

So, as a society we all are poorest Because here ideology lives not people.