There’s a remark often shared by fathers in Lahore that has woven itself into the fabric of local lore. It’s a sentiment echoed whenever one comes across the ubiquitous ‘challi wala’ — the street vendor might just be the smartest individual in the city. This is attributed to his remarkable achievement — he has harnessed the elemental power of fire within a portable wooden contraption of his own design.

These ‘challi walas’, or ‘bhutta walas’ as they are known to those from Karachi, are ubiquitous on our roads from Karachi to Kashmir. They have a knack for setting up shop in the most unlikely places — often the busiest and most congested parts of the road. Despite their relentless evasion of local authorities who attempt to dismantle their stalls, they persist — however, they might have now piqued the interest of a new patron.

This new patron is not one to quibble over whether the corn on offer is priced at Rs 40 or Rs 50. Instead, this buyer bought a staggering $341 million worth of corn in April alone. It is the largest importer of the commodity: China.

One might ponder, what could the colossus to our East possibly want with our seemingly innocuous ‘chali wala’? The answer lies in the intricate web of international politics — specifically, the ongoing Sino-American trade war, which has thrust this humble crop into its crosshairs. As a result, Beijing is on an unprecedented shopping spree for new suppliers.

So, where does Pakistan fit into this intricate puzzle? Well, we’re actually quite proficient at cultivating this crop. The only caveat is that we’re not quite there yet. This is the story of how Pakistan is set to miss out on the gold rush for what could be termed as ‘the other gold’.

Why are we on about corn?

Corn, or maize as it’s also known, isn’t merely significant for the reasons that might spring to mind. Its true importance lies elsewhere — in its role as a fundamental component of animal feed.

Regarded as a primary ingredient in farm animal feed, corn constitutes approximately half of the feed composition. It serves as a dependable source of carbohydrates and is brimming with fibre, minerals, and vitamins. Beyond the grain itself, other parts of the corn plant — such as the cobs and stalks — are also utilised as animal feeding materials, supplementing other feed ingredients. Its prevalence is particularly noticeable in poultry feed. To put it into perspective, 75% of China’s and 40% of the USA’s corn is used precisely for this purpose, according to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). As China’s standard of living increases, so does its meat consumption, and subsequently its poultry consumption.

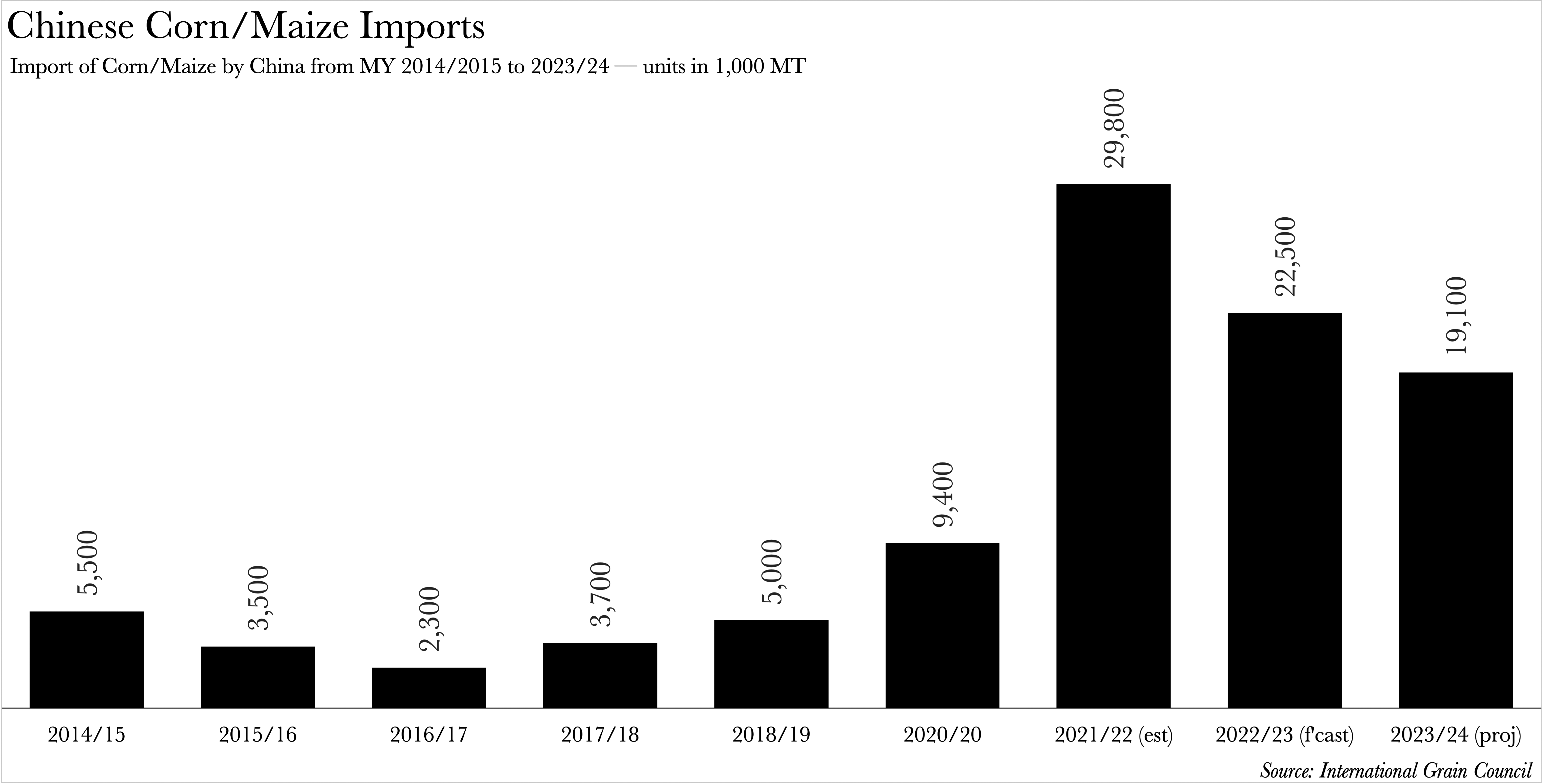

There are two additional facets to consider: firstly, the USA holds the title for being the world’s largest corn producer; secondly, China stands as the world’s largest corn importer. The equation becomes clear — China has been fervently seeking new sources of corn throughout 2023, with Brazil and South Africa emerging as the most recent import destinations. It ordered 68,000 tons of Brazilian corn in January and 53,000 tons of corn from South Africa — in a first of its kind orders — and cancelled an order for 562,800 tons of corn from the USA in the last week of April. What in the world is going on?

China’s decision is inextricably intertwined with its escalating discord with the USA. This saga, a tit-for-tat tariff duel, traces its roots back to the inception of the trade war in 2018. It was during this tumultuous period that the USA — levelling accusations of unjust trading practices, and intellectual property pilfering against China — initiated an economic skirmish. Conversely, China — interpreting these actions as a calculated attempt by the US to stifle its ascension — began to decouple itself from the USA. This series of events has now culminated in this scramble for corn.

Ahh, globalisation.

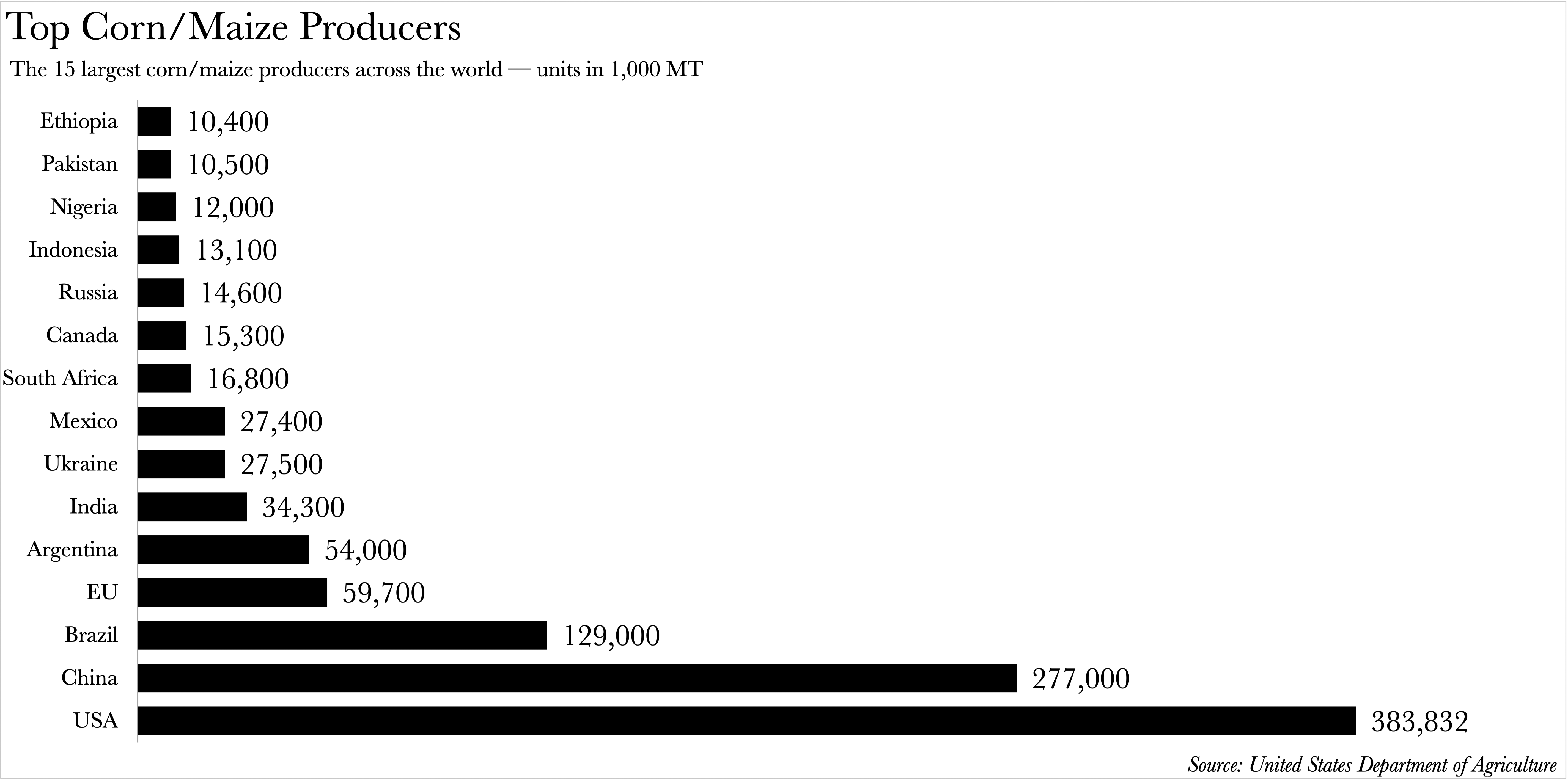

So, how does this global corn narrative affect us? Well, for starters, Pakistan ranks as the 14th largest producer of corn worldwide. More importantly, when we set aside absolute numbers and focus on relative figures, we’re actually quite decent.

And let’s not forget our status as an ‘iron brother’ to China — the world’s largest corn importer that is currently in need of new supply sources. A new supplier to potentially replace the $5.21 billion worth of corn it imported from the USA just last year alone.

Dark horse of crops

“Maize is the best news to have come out of our agricultural sector,” proclaims Kazim Saeed, the Co-Founder and Strategy Advisor of the Pakistan Agricultural Coalition.

“In the two decades that have unfurled since the inception of the 21st century, maize yields in Pakistan have skyrocketed to unparalleled heights, tripling in magnitude. While the acreage has witnessed a modest augmentation, it’s predominantly the yield that’s been the driving force behind this astronomical rise. Last year, output surged to a staggering 10 million tons, catapulting maize to the coveted position of the second-largest crop in Pakistan, nipping at the heels of wheat,” Saeed added.

Saeed’s ebullience is well-justified. A scant two years ago, corn usurped rice to ascend to the throne as Pakistan’s second-largest crop. Although it still constitutes only half of wheat’s total yield, corn has undergone a formidable ascent over the past decade. According to data from the USDA, Pakistan’s corn production has burgeoned at a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8% from market year 2013/14 to market year 2023/24. This stands in stark contrast to rice’s modest 3% CAGR and wheat’s negligible 1% CAGR over the same period.

“You’re probably pondering how Pakistani farmers managed to orchestrate this remarkable feat? The primary catalyst for this was the government’s decision to permit the import of hybrid seeds in 2001,” Saeed expounds.

“The potential for higher yield was then bolstered by domestic demand. The expansion has been entirely domestically driven — this is perhaps why you don’t hear much about the extraordinary strides we’ve made in maize production. The primary engine fuelling maize’s growth trajectory is the poultry industry. Estimates suggest that between two-thirds and three-quarters of total maize production is consumed by poultry feed,” Saeed elucidates.

In effect, we witness the surge in maize production first-hand every day. Consider all the chicken in our biryanis, or the rise in fast food consumption — all these seemingly disparate threads intertwine back to the maize that nourishes the poultry sector.

Muhammad Saeed Akhtar, Director of Operations at Rafhan Maize, one of Pakistan’s oldest and largest corn refineries, agrees.

“The poultry sector undeniably reigns supreme as the most voracious consumer of maize. Other contributors to the maize appetite include the realm of cattle farming. In addition, there exist 2-3 substantial corn processing behemoths akin to ours that significantly harness maize. The remainder of the industry is an amalgamation of medium to petite players who exploit corn in accordance with their individual capacities,” commented Akhtar.

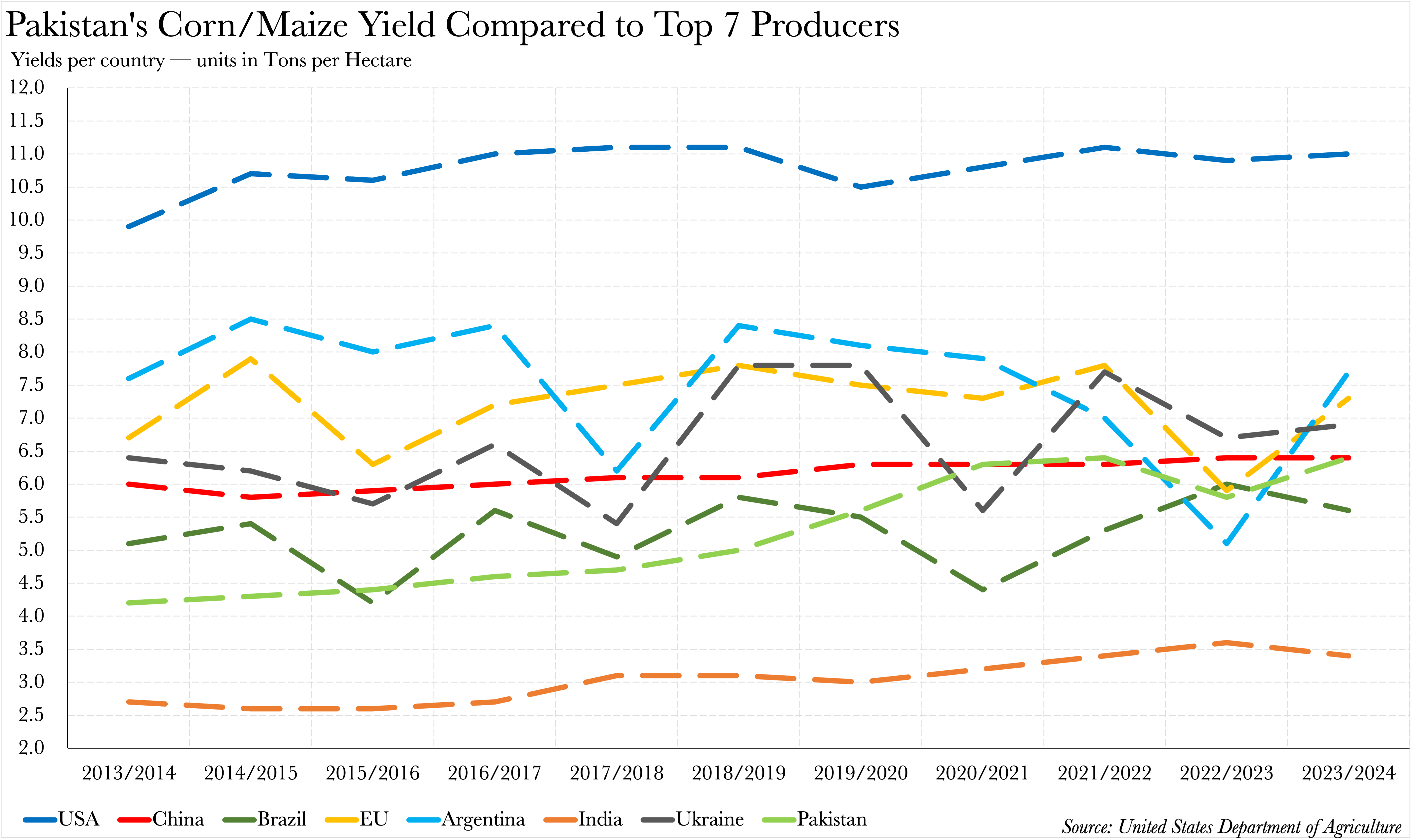

Looking at Pakistan’s yield in tons per hectare also paints a very pleasant picture. Of the seven largest corn producers in the world, Pakistan’s yield per hectare is better than two of them: India and the EU. Furthermore, it’s at the same level as China — the country we want to export to. At 6.4 tons per hectare, it also falls very shortly behind Ukraine’s 6.9 tons per hectare.

However, this is where our optimism comes to an end.

Stay at home crop

The export figures for corn in Pakistan, to put it mildly, are rather underwhelming. Our exports reached their zenith in 2021, surpassing 700,000 metric tons, only to experience a precipitous decline thereafter. This stands in stark contrast to wheat, which, despite not having breached the 700,000 metric ton threshold in recent times, has managed to maintain a considerably more stable export volume of between 500,000 and 600,000 metric tons. Rice, on the other hand, has consistently surpassed the formidable 3 million tons mark in terms of exports.

Given the current trends and market dynamics, these figures, particularly for corn, are unlikely to undergo any dramatic transformations in the near future.

How we’re set to miss out on the gold rush

In 2021, Pakistan’s maize fetched an average price of $287 per ton in the international market. This stands in stark contrast to the global price of $259 per ton. So why does our crop command a higher price? Because of the conspicuous absence of genetically modified organisms (GMOs), and the cost of production.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines GMOs, or genetically modified organisms, as organisms — be it plants, animals, or microorganisms — wherein the genetic material (DNA) has been manipulated in a manner that does not occur naturally through mating and/or natural recombination.

In recent history, in addition to traditional crossbreeding, agricultural scientists have used radiation and chemicals to induce gene mutations in edible crops in attempts to achieve desired characteristics. This means there are now possibilities of extracting genes from other organisms and including them in different organisms. For example, to make a certain maize crop more resistant to cold, scientists might extract a gene from a fish that swims in icy waters and inject it in the maize. By and large the scientific community has upheld that GMOs are safe.

Despite this, a continuous discourse surrounds the health implications linked with GMOs.The GMO question is one that haunts the entire agricultural industry of the world. This little fact benefits Pakistan. European markets do not accept modified maize and the Chinese market is also willing to pay a higher price for non-GMO maize. But then there is another issue. Because Pakistan is not using GMOs, our yield is low so there is less corn for us to export. On top of this, because our farms are not mechanised and farmers are not highly skilled, the cost of producing this non GMO corn is very high. Labour is very expensive because of factors like manual sowing and inefficient methods.

“At the heart of the conundrum lies the contrast between the global market prices for the crop and our homegrown cost of production,” elucidates Akhtar, with a tone of concern.

An ideal situation would be to grow the high value non GMO corn but mechanise farms and provide farmers the right tools. This would essentially set Pakistan up as an important exporter that deals in high-quality maize. Separately, GMO corn could be grown in different regions aimed at markets more willing to accept GMO foods.

Better luck next time?

“One must contemplate how to render their sector sustainable. The prevailing discourse revolves around capitalising on the current opportunity presented by the Sino-American trade conflict. Analogous discussions emerged during the Russo-Ukraine war,” explains Akhtar.

“The inherent uncertainty of such opportunities is their unpredictable duration, which complicates long-term investment decisions. Formulating policies based on isolated events is impractical,” Akhtar ruminates.

Guess our challi walas aren’t going to be going to Beijing or Shanghai anytime soon then.

I have done farming, why the heck that the author is saying GMO maize is good. Just say no to GMO maize, soybeans, canola and try to go organic. Do you think china is going import such expensive non-gmo maize/corn from Pakistan?? Why only China??

Still into farming? Gone organic? How are yields? How do you manage pest and weed control?

China don’t like to buy, they like to sell things.