In 2017, Jazz made a mistake. In the face of the rising threat of tech to the telecommunication industry, they launched an application by the name of Veon, which is also the name of Jazz’s Dutch parent company.

The concept was simple. The Veon app would be what is known as a Super-App. Sort of like WeChat in China, which does everything from ride-hailing to payments, entertainment, and anything else under the sun. The experiment failed.

Now, they’re back to trying the same thing. In addition to the news that Jazz would be going public and listing on the stock exchange, the company is on a mission to once again step away from their telco routes and get into the digital game.

Except this time they’re doing things a little differently. Instead of trying to create one big Super-App, Jazz is launching a number of different applications. These apps, ranging from messaging platforms to entertainment, will break down the Super-App into more digestible pieces.

Why is Jazz doing this? Easy. Telcos the world over have over the past decade faced a harsh reality. The business has low-margins for starters. On top of this, they provide mobile broadband data at cheap rates in competitive environments which people then use to operate apps like Whatsapp. This is the very same application that is the competitor for telcos because of its easier interface for calling and texting.

But will they manage to pull it off this time around?

The first play

Jazz was ahead of the game. The first 3G and 4G internet being provided by telcos hit the markets back in 2014. Up until this point, the main mode of telephonic communication for most people was through phone calls and SMS. But with the advent of this new technology, the adoption of different messaging services was very quickly adopted. Initially, Viber became popular in Pakistan before a larger shift to Whatsapp was seen.

These applications offered seamless calling and messaging for free as long as you had internet. With 3G and 4G available, people were moving towards using these “free” services much more than regular telco calling and messaging. This meant that these telcos were now providing the broadband data that was helping to cannibalise their calling and messaging business.

Jazz picked up on this quickly. Owing to this threat Veon was launched by Jazz in October 2017 as a multipurpose app with the vision of becoming Pakistan’s version of WeChat. They essentially figured out that if Pakistanis were switching to broadband based messaging, they would provide the platform to them along with the broadband internet. Aamir Ibrahim, Jazz’s CEO, had emphasised the necessity of innovation, stating that the risk of not taking the leap into app development was far greater than the risk of failure.

This initiative aimed to integrate various functionalities, such as messaging service, news feeds, self-service mobile top-ups, and cellular bill payments, into a single platform. By creating an all-in-one app, Jazz hoped to attract a large user base, subsequently generating revenue through service sales and advertising. The concept was to offer a seamless digital experience to Pakistani users, much like how WeChat operates in China.

But it wasn’t going to be easy creating a Pakistani WeChat. The success of WeChat is largely attributed to the Chinese government’s stringent internet policies, which restrict foreign competitors and allow domestic apps to flourish. WeChat’s comprehensive features and integration into daily life have made it an indispensable tool for Chinese users, encompassing everything from communication to financial transactions. This ecosystem approach has turned WeChat into a dominant player, deeply embedded in the digital lives of its users.

Veon, of course, would still be cannibalising the calling and texting revenue of Jazz. But as Amir Ibrahim said back then, it was better that their own app was doing so than any other competitor such as Whatsapp.

The service was offered free for Jazz sim owners but had a charge for users from other telcos. Not only would this have lured customers from other networks over to Jazz, the users on the app would have generated revenue through selling services as well as through ad revenue.

Veon’s road was laden with obstacles. For starters, they quickly found out Pakistan’s digital environment is not comparable to China’s. Unlike China, Pakistan does not impose strict restrictions on foreign apps, which means global giants like Facebook, WhatsApp, and Google dominate the market. Veon struggled to compete against these established platforms, which already had a vast user base in Pakistan. Additionally, operational challenges, such as changes in partnerships and strategic missteps, further hindered Veon’s ability to gain traction.

Aamir was candid enough to then say that the company had tried to do too many things on a single app and that the initial Veon platform was not strong enough, leading to a response that was not up to the expectations of the management. In a later interview with Profit, an official from Jazz disclosed that the Veon app had technological issues because of which users couldn’t place calls or the sent messages wouldn’t be received which resulted in the app’s failure.

Veon’s failure highlighted the risks Jazz faced in trying to diversify beyond traditional telecom services. The attempt to replicate WeChat’s success without a similar regulatory environment and existing user behaviours proved overly optimistic. Jazz had to contend with the reality that while their infrastructure supported innovative applications, the competitive landscape was not conducive to a homegrown super app displacing established global players. This experience underscored the necessity for Jazz to focus on more viable growth areas, such as JazzCash, which showed greater potential in the local market.

Veon’s launch was a bold step, especially given the competitive and regulatory landscape. Jazz’s strategy of offering Veon services for free to its customers — regardless of their credit balance — raised concerns among competitors. This move had the potential to attract users from other networks, further intensifying competition. And the competition did not just idly stand by and watch. Zong, for instance, responded by offering unlimited access to WhatsApp services, highlighting the aggressive tactics adopted by competitors to counteract Veon’s influence. Despite these competitive pressures, Jazz remained committed to its vision. The company’s CEO, Aamir Ibrahim, emphasised the necessity of adapting to the changing market to avoid becoming obsolete.

And the challenge wasn’t just going to be Whatsapp or other messaging services anymore.

So what happened?

Veon did not catch on. Its downloads in Pakistan were low, adaptability proved difficult, and customer acquisition never really caught on. At the same time, Jazz had other things to focus on. They had launched Jazz Cash in 2012 and continued to grow the fintech enterprise.

It became clear over time that the competition was not just platforms like Whatsapp and Viber. It was also other platforms such as Instagram and Facebook which provided entertainment as well as messaging. People were using their data watch and scroll content on these platforms. In 2019, after the failure of the Super App dream, Veon was shelved.

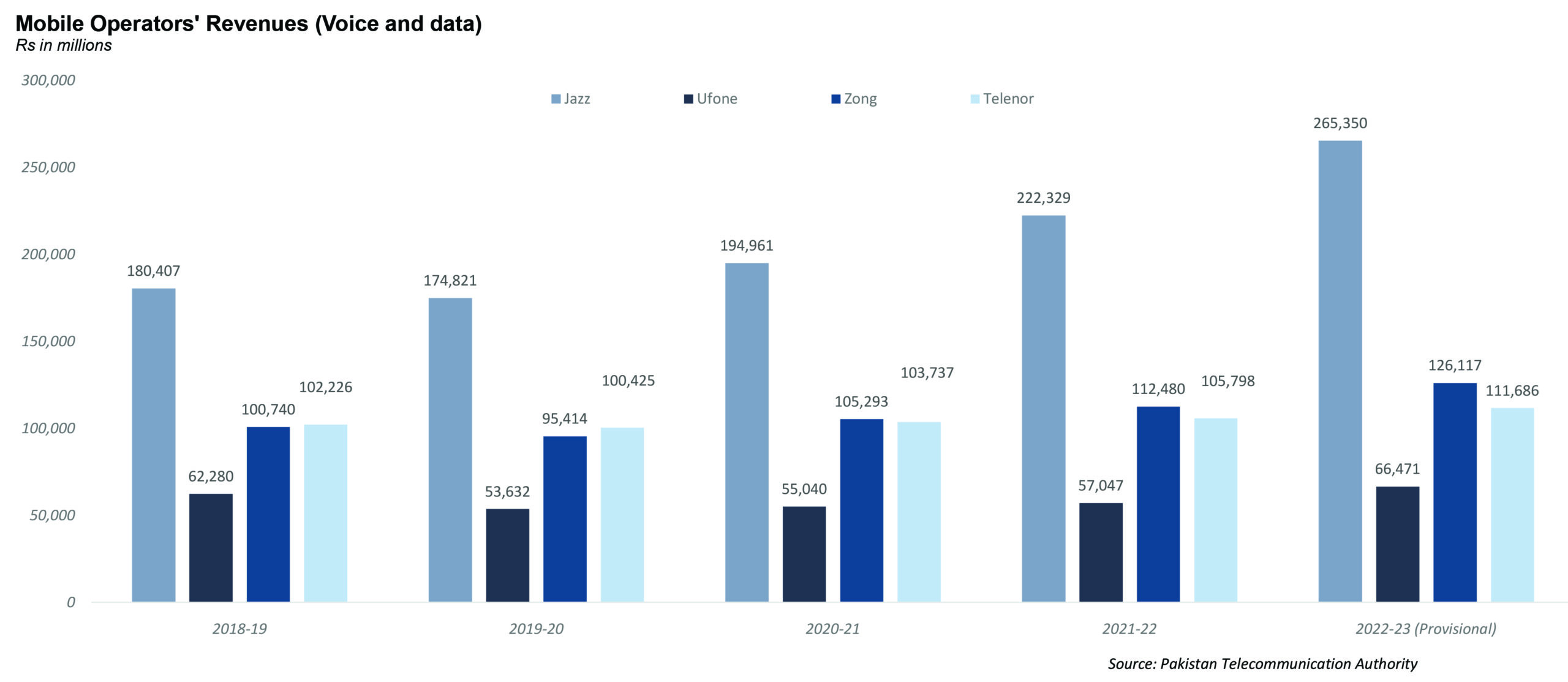

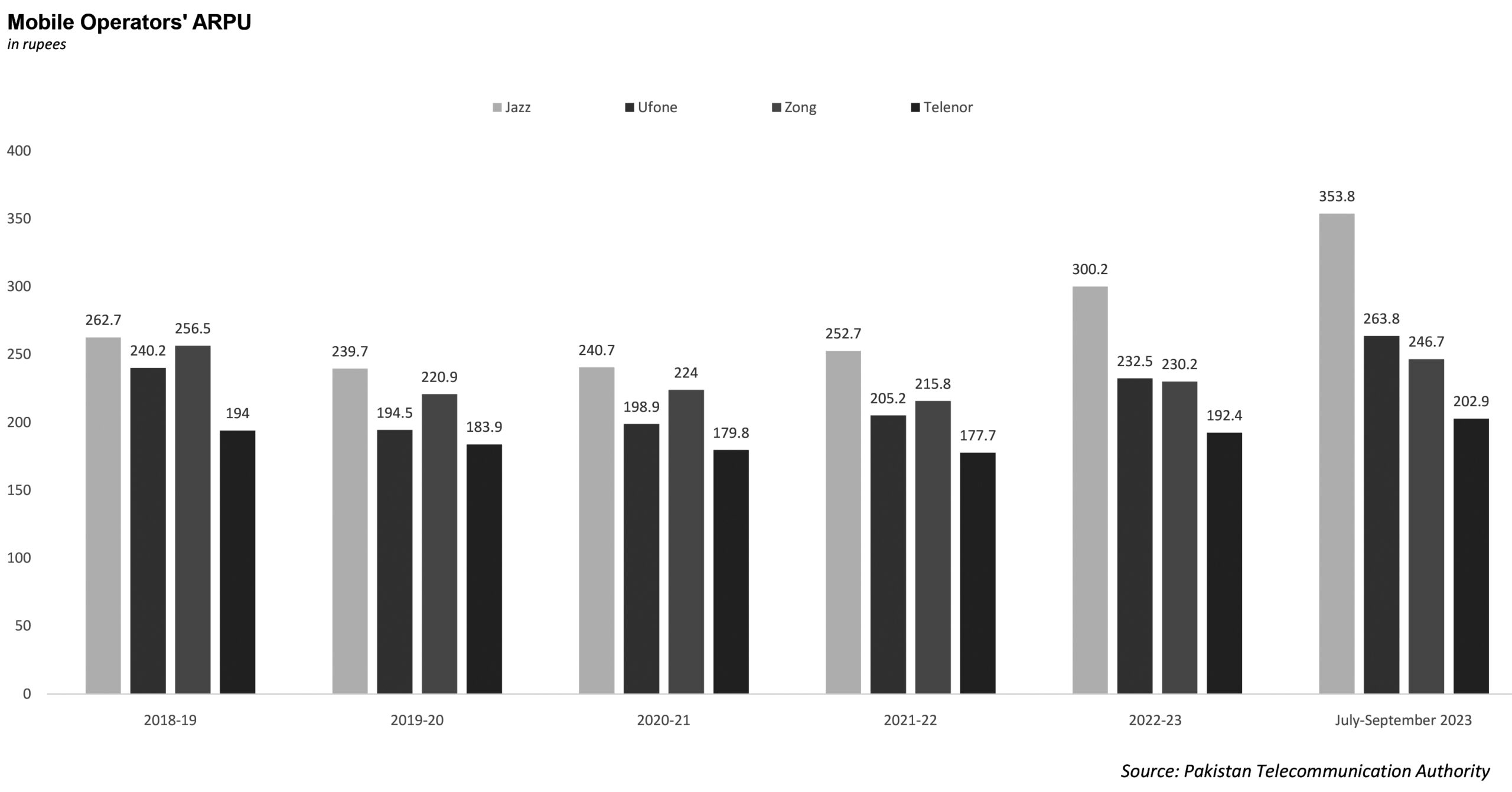

During this time, profitability for telcos fell overall. The way this industry calculates its earnings is through a system known as ARPU — average revenue per user. Earlier this year, Telenor exited Pakistan citing the fact that they had a persistently low ARPU of around $1. For them to be viable, the company needed to raise this number to at least $1.5.

The main problem for all telcos has been that they operate in an environment with multiple competitors and very low margins.The market is oversaturated with three players even after the exit of Telenor. On top of this, inflation has meant consistently rising costs of doing business.

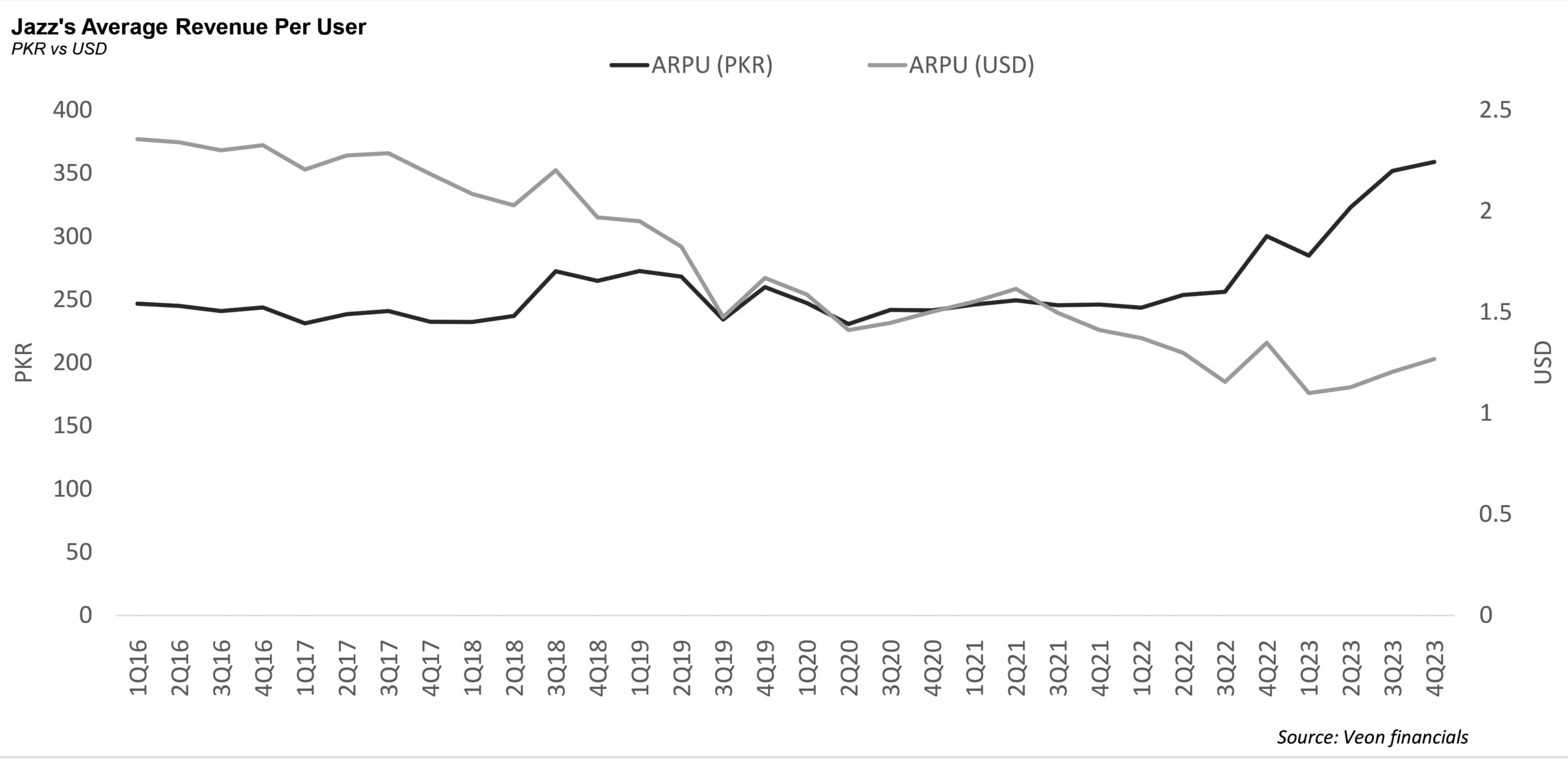

Just take a look at how Veon has performed in recent times. In 2023, their total revenue grew by nearly 20% and EBITDA grew by 4.9%. But multinationals like Veon (Jazz’s parent company) evaluate the performance of their local subsidiaries in dollars and this is also the currency in which the subsidiaries will be valued so any significant devaluation of domestic currency would have ramifications for local subsidiaries. This is exactly the case with the Pakistani rupee and Jazz.

Thus in dollar terms, the revenue in Pakistan was down by 12.9% in 2023 compared to 2022, and the EBITDA was down by 23%.

Further, the ARPU in dollars also paints a contrasting picture when compared to the same in rupee. While the ARPU in rupees has been growing consistently, and Jazz has the highest ARPU growth compared to others, the growth in dollar terms is not proportionate.

Jazz goes to bat again

But Jazz never really gave up on the Super App dream. It just changed how it wanted to implement it. It began what it named its “Digital Operator 1440” strategy, also being implemented by its parent company VEON in other markets such as Bangladdesh and Ukraine. The name comes from the 1440 minutes that are there in a day. The goal was for Jazz to gain the attention of its users for as many of these minutes as possible.

Jazz’s recent investment of over Rs5.3 billion in the first quarter of 2024 reflects its commitment to fortifying its digital presence and the increasing focus towards becoming a tech company. Additionally, Jazz’s recent issuance of a Rs15 billion Sukuk marks a strategic move to bolster its financial liquidity, enabling further development of its digital services portfolio.

This transition to digital not only mirrors the shift from conventional telecom to services that people want to spend their data and time on (OTT services is the technical term). The idea is that because OTT services are available over the internet it leads to an increase in data consumption of telcos. But if a telco itself has multiple applications and the telco is able to keep users engaged on these apps, not only could this counter the threat from OTTs but would also incrementally increase revenue from selling data. That is besides, these apps have their own sources of monetization as well.

As part of this new strategy, Jazz is launching a number of new apps. Some of them are challenging existing platforms for consumer attention. These are apps that offer messaging services, entertainment, and other facilities. And then there are other new business streams Jazz is launching. These include streams that do not have anything even remotely to do with their initial telco operations.

The following is an overview of what each platform is meant to do and what challengers it hopes to take on.

Tamasha

Perhaps more than anything, Tamasha represents what Jazz is trying to achieve. The platform has emerged as the largest digital cable service in the country, offering over 75 TV channels, video-on-demand (VOD) options, and some international content. Its extensive coverage includes 20 cricket tournaments, generating 8 billion minutes of viewing time. With 12-13 million monthly active users and 2-2.5 million daily active users, 40% of whom are non-Jazz customers, Tamasha has become a significant player in the OTT space. In 2023 alone, it attracted Rs 600-700 million in ad revenue, highlighting its commercial viability.

On Tuesday, Jazz announced that it had secured digital streaming rights for ICC cricket tournaments in 2024 and 2025 for Tamasha app. This has allowed the app to gain many initial users, something it failed to do with the Veon platform. But there are some problems with this. There are a few ways for platforms such as Tamasha to make money, and the key is content. The first method is to be like Youtube, which allows consumers to upload their own content and then runs ads for revenue. The second method is to be like Netflix, control their content, and ask for money for subscriptions.

Ideally for Tamasha, what they would do is create their own content such as television dramas or even news and run ads to make money. As things stand right now, Tamasha is only picking up content from others. And the day they cannot win the bid for digital rights to cricket, their business model would fall flat.

So far, its mainstay for monetization includes streaming of live cricket and that could be a problem. There are multiple other options for watching live cricket, one of them being television channels which are the dominant mode for watching sports. Digital streaming rights are also not awarded for life which means that as soon as these rights go to some other OTT platform, the revenue stream gets in trouble.

While Jazz has produced exclusive content, the volume is small. But executives say they are on track to produce more as well. The competition in this space is also very tough with the formidable presence of Youtube that allows outside creators to post exclusive content, as well as competition from other OTT platforms like Netflix and Amazon Prime. Local platforms such as Begin and Tapmad, as well as Daraz which recently ventured into streaming live cricket are also rising. On top of this, Jazz currently does not have a team of creatives for content on the Tamasha app.

JazzCash

This is perhaps the biggest success story Jazz has. The app that needs no introduction has become an integral component of financial inclusion in Pakistan. JazzCash is among the top apps, ahead of many of the banks. The jewel in Jazz’s crown with 44 million wallets, JazzCash allows its users cash-in and cash-out services through a network of branchless banking agents, in app payments transactions, and disbursement of loans from the books of Mobilink Microfinance Bank. All of this makes JazzCash a lucrative venture and the top app under Jazz’s DO1440 strategy.

As Jazz moves forward with its strategy, it plans to further solidify JazzCash’s position in the digital financial services segment by making it an embedded finance app. Other than increasing their focus on lending, the products that Jazz plans to introduce on JazzCash include insurance, wealth management, and the investment products such as in gold and real estate via tokenization.

Sim One Super App (Simosa)

This one is a case of trying to use every piece of the cow. Simosa is the rebranded version of JazzWorld. It offers users a platform to manage their Jazz accounts, access faith-related content, read news, and play games. As a lifestyle app, Simosa is designed to serve as a one-stop-shop for multiple needs and sells digital ad space. The idea is to make Simosa an everyday app and give enough functionalities that users start spending a considerable time on the app. The problem, however, is that the app is pretty much something users would use once a month to recharge their accounts.

The road to monetization is going to be rough for the Simosa app, given that Simosa is primarily an app for Jazz customers to manage their accounts such as managing packages, activities that are not done on a frequent basis, weekly or monthly. Though the platform could be opened for other telcos as well and is in works, it is going to be a challenging task to have competitors on the app that is owned by the largest telco. The other functionalities such as faith have established competition from apps like Islam360 that offer more functionalities than Simosa’s faith section.

Rox

Rox, an app similar to Simosa that caters to a younger audience, also offers a range of services designed to cater to the diverse needs of its users. These services include telecom offerings such as voice and data bundles, along with an array of digital perks. By partnering with leading lifestyle brands like foodpanda, Careem, and Bookme, Rox provides users with exclusive deals and discounts, enhancing their digital lifestyle.

BiP

This one is a shot in the dark. BiP is a messaging app. The problem is it seems difficult to compete with Whatsapp, which has slowly become the default messaging platform for Pakistanis. BiP is a Turkish messaging service owned by Turkcell and Jazz has launched it in Pakistan in partnership with its Turkish counterpart. Its development aligns with Jazz’s strategy to capture a share of the messaging app market by offering a locally-tailored alternative.

The chances of BiP working in Pakistan understandably look slim because of the dominant presence of WhatsApp which is popular even in the lowest strata of the country. It could work if regulators in Pakistan decide to limit WhatsApp functionalities in Pakistan just like regulators in countries in the Middle East have done, or ban WhatsApp altogether. On top of WhatsApp, there is also a presence of services like Zoom, Google Meets, Teams and Skype, leaving less room for another messaging app to become successful.

But Jazz could have something up the sleeves: in a potentially disruptive move, BiP, an internet-based service, could call on your landline or cell phone number on any network. There is still a big number of feature phones in Pakistan which can not use any internet dependent OTT services. About 40% of the phones in Pakistan are still feature phones. Smartphone users that use BiP could call feature phone users through this option which is not available on WhatsApp or any other app. For Jazz users, BiP could be functional even without the internet if they are near a Jazz tower.

While calls like these are technically possible, this would have to clear any regulatory bottlenecks before it could be launched. With this function, BiP would have the chance to become a success. There is also another possibility. If the government of Pakistan at any point decides to ban Whatsapp (as it has done with Twitter currently and Youtube in the past), Jazz could have an opening with BiP. But that is something entirely out of their control.

Garaj

This is where we get to the part where Jazz is introducing business vertices that are not in the slightest to do with any of their previous business interests.

Launched after Pakistan’s Cloud First Policy was introduced in 2022, Garaj not only hosts Jazz’s suite of apps but also provides services to businesses in different sectors forming a new revenue stream. Serving 300 customers and targeting specific sectors like financial services and healthcare, Garaj exemplifies Jazz’s innovative approach to leveraging cloud technology for business growth.

Quantica

Launched in November 2023, Quantica allows telcos to monetize the vast amounts of data generated by their networks. By anonymizing and aggregating this data, Quantica provides valuable insights to its business customers, allowing them better decision making. Quantica offers two primary services which help solve business problems through a combination of customer data and insights generated from Jazz’s data, thus enhancing business decision-making.

What can Jazz do with this?

Jazz is trying to do a lot here. One might even say they are getting a little desperate with it. But that desperation is good. Jazz is perhaps the only telco not just realising the problems that exist in their industry, but are very actively doing a lot to try and fight back.

The years to come might prove to change Jazz entirely. Currently, the telco business and Jazz Cash are the biggest businesses they have at their disposal. But it is entirely possible if even one of their new ventures or attempts takes off, that it becomes the identity of Jazz a decade from now.

What do the numbers say about how they are doing currently with this new strategy? Seemingly, Jazz is on the right trajectory. In the first quarter of 2024, Jazz showcased significant growth across its digital and fintech services, reflecting a strong performance trajectory. The total revenues soared by 28.7% year-over-year (19.2% in USD terms), primarily fueled by an increase in 4G user adoption and strategic inflationary pricing adjustments.

This growth strategy led to a 30.3% increase in average ARPU. Particularly impressive was the performance of Jazz’s fintech service, JazzCash, which saw service revenues skyrocket by 98.0% YoY, demonstrating robust growth in this segment.

Jazz continued to enhance its digital services portfolio, evidenced by a 25.5% YoY increase in multiplay customers who engage with offerings such as JazzCash, Simosa and Tamasha.

These multiplay customers now constitute 28.9% of Jazz’s monthly active consumer base, significantly contributing to the operator’s revenue — accounting for 56.6% of B2C segment revenues. Furthermore, the expansion of JazzCash was highlighted by its massive customer engagement, with 7.9 million digital loans issued and a gross transaction value of Rs6.6 trillion, marking a 47.1% increase YoY.

But the problem at the end remains: if the growth does not translate into a meaningful growth in ARPU, it which still hovers around $1, becomes increasingly difficult to sustain. High-ranking executives from Jazz have also told Profit in background conversation that ARPU remains the biggest concern for the telco and that despite the launch of multiple digital services, ARPU was not growing promisingly.

Perhaps it is because Jazz digital services still form less than 15% of the company’s revenues. As this revenue grows, more ARPU could be expected but that remains uncertain because monetizing the apps would remain a challenge as explained above. What is certain is that Jazz’s transformation towards becoming a technology company has begun and there could come a time when revenues from digital services could match or possibly exceed revenues from telecom services, changing Jazz’s distinction as a telecom company permanently.