There was a rare bit of unity at the Karachi City Council in the middle of May. Packed into the assembly hall like sardines in the Karachi heat, members from the PTI, PPP, and JI were all united in their opposition to one entity: K-Electric (KE).

The anger came from hours of unscheduled load shedding in different parts of Karachi that had left the metropol’s population (the constituents of the good councillors) incensed. The power outages come from a years old strategy of KE and other distribution companies of revenue-based load shedding, in which these companies cut power in areas where electricity theft is high and the recovery of billables is low.

It is a strategy that has come under very particular scrutiny and controversy this year, and has pitted the federal government, NEPRA, Karachi’s local government, different political parties, and KE’s owners against each other.

What most might not realise is that this controversial back and forth is happening at a time when a massive cloud of uncertainty hangs over the future of Pakistan’s oldest and only vertically integrated electricity company. The uncertainty in question is over a disturbingly fundamental matter: Who owns K-Electric?

Back in 2023, the ownership of KE had changed hands. The company, once an Abraaj asset, was sold to AsiaPak Investments in a deal that took place in the Cayman Islands far away from Pakistani regulators and stakeholders. AsiaPak is run by Sheheryar Chishty, a former highflying banker who now owns Daewoo in Pakistan and has deep interests in Thar Energy.

Despite more than a year passing, Mr Chishty and his company have not been allowed to take the reins of the KE management. Behind this delay is a tussle between the new regime and some of the company’s minority shareholders. And as per the new owners, they have a plan for KE that might just turn things around. But if the status quo continues, how much of KE will be left for Mr Chishty to turn around?

How we got here

A great deal can be seen through the company’s corporate history. Let’s start at the beginning.

Thirty-two years after Thomas Edison created the world’s first utility company in Lower Manhattan, the Karachi Electric Supply Company (KESC) was founded in 1913 (rebranded in 2013 as K-Electric). It is the country’s only vertically integrated utility, with its own power generation, transmission, and distribution assets. Until the late 1960s, KESC was largely a financially self-sustaining entity. In the 1980s, the company briefly became a subsidiary of the Water and Power Development Authority (WAPDA) and was at one point placed under the management of the Pakistan Army.

The modern history of K-Electric that is relevant to us now begins after all of this. In 2005, the Musharraf Administration sold off a 66.4% stake of the company to a consortium of the Al-Jomaih Holding Company, a diversified Saudi Conglomerate, and the National Industries Group, a publicly listed Kuwaiti financial conglomerate (which also owns a large stake in Meezan Bank). For three years, the Saudi-Kuwaiti conglomerate failed to make any headway in turning around the company, finally turning in 2008 to Arif Naqvi, the former Karachiite who had gone on to create Abraaj Capital in Dubai.

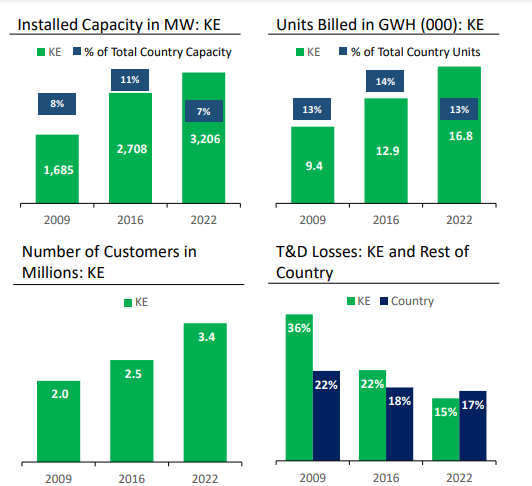

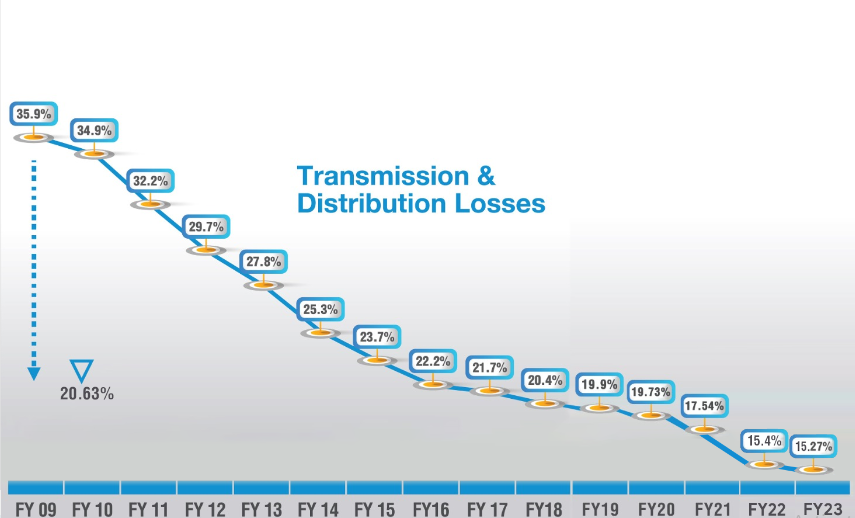

Abraaj was already the largest private equity firm in the Middle East by then, and had previously made forays into the Pakistani market before. In October 2008, Abraaj bought out half of the Jomaih-NIG stake in KESC, injecting $391 million into the company. It then began a turnaround effort the likes of which have never been seen in Pakistan before. Abraaj spared no expense in trying to turn around KESC, investing upwards of $1 billion in the company’s power generation and transmission infrastructure, which brought the utility’s power generation efficiency rate from 30% in 2008 to 37%. As per KE’s own numbers, from 2009 when Abraaj took over KE’s transmission and distribution (T&D) losses were 35.9%. By 2019 this number had fallen to just under 20%.

This was a bonafide come-from-behind recovery.

During this journey, Abraaj was ready to reap their rewards. They had taken KE on at a time when the company was a loss making entity (they made losses up until 2011-12) and turned it into a profitable power company. In 2016, they sold 66.4% of K-Electric to Shanghai Electric, the Chinese power company, for a whopping $1.7 billion making it the biggest acquisition of a Pakistani company in a decade.

This was always the plan for Abraaj. It is the very reason private equity firms came into existence in the first place. Abraaj came in, took control of a storied company with a unique economic purpose that had been sullied by bad management and turned it around through a combination of strategic capital investments and modern management techniques. Now they were ready to sell it off in a healthy, relatively unleveraged state to a strategic buyer.

Except what seemed like a deal made in the stars was cursed. To cut a very long story short, consistent delays on the part of the government meant the Shanghai deal could not go through. Despite a lot of political lobbying on the part of Abraaj’s Arif Naqvi, the deal was dead in its tracks. And then came the crash. In 2019, Arif Naqvi and Abraaj were involved in an international scandal that ended with the company utterly bankrupt. And along with it the Shanghai Electric deal went kaput. For six years Abraaj’s baggage weighed the Shanghai deal down and KE remained unsold.

Situationer: Where KE stands

As tough a year as it was for Arif Naqvi and Abraaj, 2019 was no bed of roses for K-Electric. Place the company in its context. For decades the company was a self-sustaining profitable entity. It met an unfortunate fate in the form of nationalisation and bounced around different government departments before finally being bought by a private equity company which set it straight and back to making money and providing its services efficiently. But when time came for a permanent new owner to take over, disaster struck.

At this time KE was under steady leadership. Moonis Alvi has been the CEO of the company since June 2018, a year before Abraaj came crashing down. Mr Alvi is an old hand at KE, and was one of the architects of its revival under Abraaj having been part of the team since 2008. He was the company’s CFO before his elevation to the top job.

So when it became clear Abraaj was done for, there was still a steady, stabilising hand available to keep the ship afloat. Mr Alvi continued in the same way that things had been going. Transmission and distribution losses continued to fall and have come down to as low as 15.27% compared to the 35.9% that existed when Abraaj first took over in 2008.

But keeping things afloat can only go on for so long. From 2019 onwards KE was in a bit of a fix. It didn’t know exactly what to do with itself, so the focus became fixing losses and increasing efficiencies in other areas such as health, safety, and environmental (HSE) standards. None of this ends up helping the bottom line significantly, and to have any sort of long-term vision you need a long-term owner. For a while many thought Shanghai Electric would still be involved and interested, and the company did keep renewing their interest in keeping the deal alive every six months.

The baggage of Abraaj proved too much and kept weighing down the deal. and KE remained unsold. That is of course until a quiet, seemingly normal September day last year.

Enter Mr Chishty

Shaheryar Chishty had been interested in K-Electric for a while. The former highflying international banker was born in Lahore, raised in Karachi in a navy family, and came back to Pakistan in 2011 where he acquired ownership of Daewoo as well as interests in CPEC backed projects regarding Thar Coal. A self-described investor in orphan assets, Mr Chishty had been impressed by the Abraaj led turn around of KE and had tried to acquire the company. At that point, CPEC was at its peak and Chinese investors were deeply interested in putting money into Pakistan. Because of his involvement in CPEC projects in the past, particularly in Thar Coal, Chishty was well connected in China and put together a consortium that would bid for control of KE. But Shanghai beat him to it.

“There were Chinese investors, other Asian investors, and a couple others with interests in KE as well but in the end Abraaj ended up receiving a very good offer from Shanghai Electric,” Mr Chishty told Profit last year.

So when the opportunity presented itself again, Mr Chishty started making moves to acquire KE, which he did in the Cayman Islands.

The assumption was that the KE management and shareholders would be happy at the acquisition because it would mean direction. The Shanghai deal was clearly not happening, and KE was not doing too well either. Just look at their financials from 2023 where the company reported its first loss in 12 years. And it wasn’t some small dip in fortunes. K-Electric bled over Rs 31 billion last year in the wake of rising electricity prices and increasing line losses.

This was a dark moment in the history of the storied company. Its problems had caught up with it. These losses were ten times greater than the Rs 3 billion loss they incurred in 2020 because of the pandemic. Even though KE had been on a mission to cut line losses and make themselves more efficient, the company was always going to be a victim of the times. In the past couple of years, power prices have been raised by the government, the rupee has depreciated, inflation has soared, and the cost of borrowing from banks has risen sharply because of the very high interest rate that has been maintained for some time now.

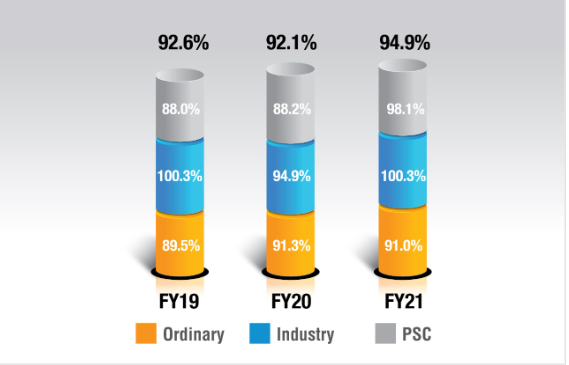

Because of inflation, people are either using less electricity or they are not paying their bills or they are stealing. This has reduced KE’s recovery ratio from 96.7% in 2022 to 92.8% in 2023. The company also supplied 7.3% less power during the year “due to reduced economic activity”.

Despite all of this Mr Chishty and his other investors have not been allowed to take management control of KE. This does not mean they haven’t been trying, and the majority shareholders actually have a detailed plan with regards to how they want to go about best utilising KE. So why don’t they get a seat at the table?

The ownership structure

What we have here is a legacy company that was in trouble, it was revived via private equity before falling victim to the very private equity firm that gave it a second life. Now, the company has new owners that have plans for it but somehow they are unable to get their foot in the door. Why is this so?

To understand this we must get to the bottom of how KE was acquired by these new owners. Profit covered this last year when the change in ownership first happened.

Read more: Who is Shaheryar Chishty and what does he want with K-Electric?

But to cut a long story short:

Since KE was owned by Abraaj, which as a company has gone bankrupt, its assets are a little all over the place. Just take a look at the ownership structure of KE. When the Al Jomaih group entered the picture in 2005, they created KES Power Limited (KESP) which was a Cayman Islands company. This company paid the government of Pakistan directly and acquired a 66.4% stake in K-Electric in Pakistan.

So when Abraaj wanted to buy KE from Al Jomaih in 2009, they funnelled over $370 million in foreign direct investment into KE through the KESP company in Cayman. This money was channelled through the Infrastructure & Growth Capital Fund L.P. (“IGCF”), a $2 billion Cayman Islands private equity fund with investment contributed by over 100 different international investors, managed then by Abraaj Investment Management.

This means KE is owned by the KESP in the Caymans, which after Abraaj’s entry is now owned by the IGCF. So when Chishty wanted to acquire Abraaj’s stake in KE, it could not acquire KE in Pakistan. It had to go to the KESP in Cayman. Chishty’s company, AsiaPak Investments, created a special purpose company called Sage Venture Group Limited (Sage) and registered it in Cayman. Sage then bought out the Infrastructure Growth and Capital Fund LP (IGCF or the Fund), which holds an indirect material stake in K-Electric Limited. These transactions were authorised in proceedings at a court in the Cayman Islands, according to court documents.

This essentially meant that Mr Chishty and his AsiaPak Investments now owned the majority of the shares in K-Electric. This did not translate to them having control of the board of KE in Pakistan, but they could easily translate this into management control in Pakistan. Well, at least in theory they could. What they did not quite expect was that some of the minority shareholders would give them a real run for their money.

The Gulf investors throw a spanner in the works

Now this is where things get interesting. Remember, what Mr Chishty has bought is a 53.8% stake in KESP, which is the company which owns 66.4% in KE. The remaining 46.2% of KESP is owned by Al-Jomaih Power, and Denham Investments. This is the same Al Jomaih that first bought KE through the KESP in 2005 before they sold it to Abraaj in 2008.

In August 2023, soon after AsiaPak acquired the IGCF which held the share in KESP (essentially Abraaj’s old position in KE), Al Jomaih used a special purpose vehicle by the name of White Crystals that had invested in the fund to bring arbitration against the general partner under an LCIA clause in the deed of limited partnership for IGCF. It is a complicated legal case that Profit has covered before.

Understanding K-Electric’s Caymans legal battle

The situation, however, is that AsiaPak essentially owns the same position in KE that Abraaj did up until it went bankrupt. And up until the Abraaj scandal blew up, the private equity fund had complete control over the KE board and could appoint its representatives onto it. This is something that through repeated legislation and stay order Mr Chishty’s AsiaPak has not been allowed to do.

Part of the reason could be the fact that the minority shareholders in question that form Al Jomaih have some serious influence within circles that matter in Pakistan. The Saudi and Kuwaiti investors that make up the consortium are people that the government does not necessarily want to get onto the bad side of. Perhaps nothing is more telling of this than reports of the Special Investment Facilitation Council getting involved in this kerfuffle. As reported by The Friday Times back in October, the Executive Committee of SIFC had set up, on the instructions of high-ups, a three-member committee to resolve issues related to the power utility.

“K-Electric is being treated as an orphan child by the shareholders, by the federal government, by the management and for whatever reason they are doing so is not my job to figure out,” explains Mr Chishty in a conversation with Profit. During the interview, it was clear the process is frustrating. And why would it not be? When you buy something, you expect you’ll be able to apply it as you see fit. As a man with a plan, he feels very little is being done to set KE on the straight path.

Did you get what you bought?

This is what it boils down to for Mr Chishty and his AsiaPak Investments. In 2022, they bought an investment that they expected to have control of and run as they saw fit as majority shareholders. Instead, they have been denied this consistently. By the time they get control (if they do any time soon that is), what state will KE be in and will their plans be viable?

As Mr Chishty explains to us, his entire approach to the problem was to focus on high cost imported fuel that KE used to produce electricity. His plan was to use his influence and experience in Thar Coal to shift Karachi onto a cheaper fuel source for its electricity.

KE is plagued by many problems. The company is plagued by problems and is far from an investor’s dream. The only thing it has going for it is the monopoly it holds over electric supply in one of the world’s largest cities. Yet even this is under threat with people slowly coming to rely more and more on home based solar solutions. As things stand, Karachi is caught in a vicious cycle of energy being insufficient, unaffordable, uncompetitive, unreliable. Unaffordable energy reduces consumer purchasing power and lowers quality of life, leads to reduced tax base, as well as growing dissatisfaction with provincial and municipal leaders.

In response to these crises, Chishty has time and again made it clear he didn’t get into this to make a quick flip. His stated goal is to come on board as a long term owner and stay the ship. But with competing energy sources such as solar fast on the heels of KE, what does he plan on doing? The problems are clearly in front of us. Over the years, KE has become sluggish and inefficient. The number of people wanting electricity has increased. According to Chishty, the solution is to make K-Electric central to a modern, thriving metropolis. And that requires Karachi to change. One of his biggest claims is that the city itself is surrounded by ample area to utilise solar and wind power. The biggest problem with solar and wind is that it is very expensive to setup for the average household. So if a utilities company like K-Electric can harvest this energy it can provide significantly cheaper electricity to households.

According to KE estimates, in the case of solar there are 20% to 22%+ capacity factors easy to achieve. There are already well-developed ecosystems vendors, EPC contractors, and operating teams in Pakistan. There is also strong interest from international financiers. According to the company’s estimate, this would require around $1.8 billion in investment. Similarly for wind energy, there is a capacity factor of over 40% which is significant. Karachi is only 50 kilometres from one of the most high potential wind corridors; and there is also strong international investment interest in this as well. The estimated investment required would be around $1.3 billion.

And then there is the biggest card that Chishty has up his sleeve to save K-Electric; Thar Coal. When you think about it, the problem is actually very simple. Pakistan relies heavily on imported fuel sources such as reliquified natural gas (RLNG) to produce electricity. Whenever there is an international crisis, such as the Russia-Ukraine war, Pakistan’s energy sector is rocked by the ripple effect. There is a simple solution. Cheaper fuel — something like coal perhaps. And the source is right there too. Spread over more than 9000 square kilometres, the Thar coal fields are one of the largest deposits of lignite coal in the world — with an estimated 175 billion tonnes of coal that according to some could solve Pakistan’s energy woes for, not decades, but centuries to come.

Discovered in the early 1990s by the Geological Survey of Pakistan (GSP), Thar Coal accounts for around 660 MW of electricity produced in the country. The potential is much greater. If new projects that are currently under construction become operational, in the next year electricity production from the Thar coalfields is expected to increase to as much as 2000MW. In short, Thar Coal offers a cheap, alternative, local source of energy that can be used to produce electricity and help Pakistan escape its topsy-turvy reliance on international markets to maintain its energy supply.

Chishty is naturally a big believer in Thar Coal. Two blocks of this project are already ready for operations. And according to a K-Electric document, the company feels they can easily be expanded at a low marginal cost. Located only 300 kilometres from Karachi, transportation is also not going to be a major expense. Already a rail line linking Thar to the national rail network is expected to be completed during 2023, and it will require an additional investment of just over $3 billion to produce 3600MW of electricity.

Using these three sources, K-Electric could increase domestic, industrial, and transport customers. And this isn’t where it ends. Chishty plans on also working with authorities in Karachi to build the City into a modern metropolis based on sustainable living. One of his goals is to introduce electric public transport and electric bikes with charging stations all over the city. Essentially, Chishty would also be synergizing his businesses. On the one hand he is in transport which can run the buses, on the other he owns KE which could provide the electricity, and he also has interest in Thar Coal which provides the raw material to create electricity in the first place.

It is a logical plan that makes sense. As the buyer of Abraaj’s position in KE, one would imagine Mr Chishty would easily be able to come in, take control, and at least see if his plan might work. Up until now, he has been denied that. As more time passes, the nature of KE will continue to change. Will the plans AsiaPak made to turn the company around still be relevant by that time? It depends entirely on how long this entire business takes.