In the early 1940s, Soviet scientists – like their German and American counterparts – were working on trying to get their country to start a nuclear weapons program. Their problem was that Joseph Stalin, the Soviet dictator, did not understand the then nascent science of nuclear physics, and was not bothered to learn anything about it either.

Then they brought him a piece of information that got his attention: the fact that American physics journals had suddenly stopped publishing papers on nuclear physics. Atomic nuclei were not something Stalin understood. Missing information, he understood instantly.

Missing information is almost never a coincidence.

Between 2005 and 2021, the government of Pakistan has published the results of a Household Integrated Economic Survey, a Social and Living Standards Measurement survey, or a Labour Force Survey either every year, or every other year. In some years, more than one survey result was published.

But after 2021, the next survey to be published was one that captured data from the fiscal year ending June 30, 2025, a gap of a full three years. These surveys are meant to measure the economic and social well-being of Pakistanis, and for all its flaws, the government has done a reasonable job of trying to measure progress on many fronts, and to make its data freely available to researchers outside the government.

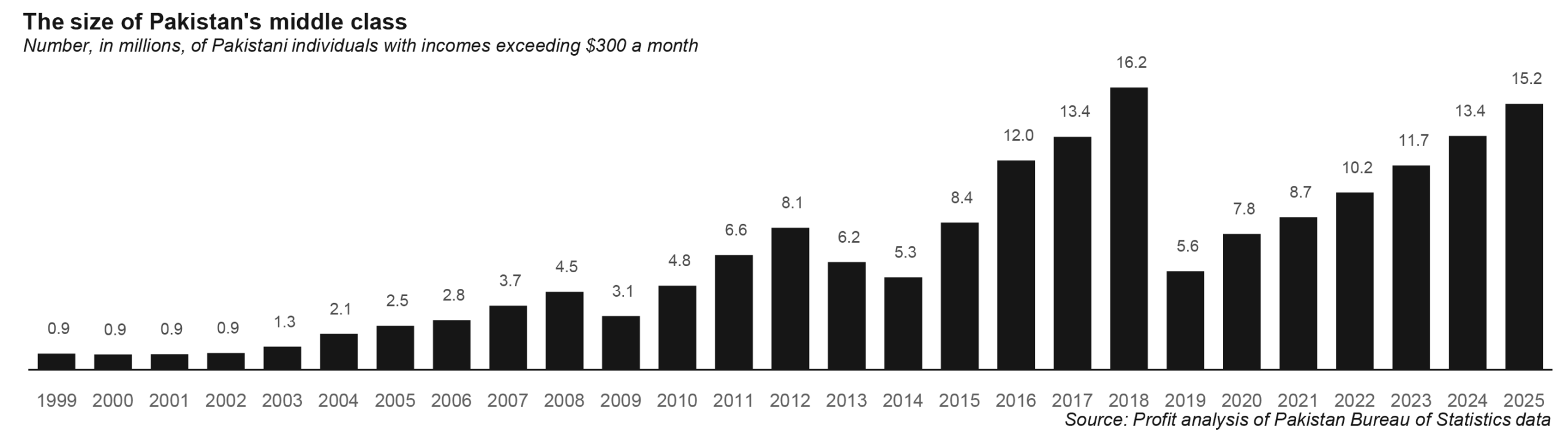

This three-year gap is the longest gap to have occurred in the collection and dissemination of this kind of data since at least 1990. Not coincidentally, the years for which data are missing happen to also be the worst years for the Pakistani economy since the aftermath of the 1971 war, as measured by GDP growth, when measured in nominal US dollar terms.

Did the government run at least one of these surveys during this period and simply not publish the results because they were unfavourable? There is no reason to believe that happened. But did the government guess that conducting such a survey would quantify the misery its citizens were going through and decide to simply not conduct the surveys? That is certainly possible.

The results of this survey reveal a middle class that continues to expand and contract based on the cyclicality of the government’s policies, specifically with respect to exchange rates. And one man, more than any in the past two decades, is responsible for the volatility of Pakistanis’ incomes and middle class insecurity: Ishaq Dar, currently the foreign minister, but the man who tends to be at the helm of the Pakistani economy whenever the Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PML-N) is in office.

Dar is obsessed with the Pakistani rupee’s exchange rate the way Gollum was obsessed with the One Ring in The Lord of the Rings: he has absolutely no actual control over it, the obsession sucks the life out of all that it touches, and yet, it remains his precioussss. The content in this publication is expensive to produce. But unlike other journalistic outfits, business publications have to cover the very organizations that directly give them advertisements. Hence, this large source of revenue, which is the lifeblood of other media houses, is severely compromised on account of Profit’s no-compromise policy when it comes to our reporting. No wonder, Profit has lost multiple ad deals, worth tens of millions of rupees, due to stories that held big businesses to account. Hence, for our work to continue unfettered, it must be supported by discerning readers who know the value of quality business journalism, not just for the economy but for the society as a whole.To read the full article, subscribe and support independent business journalism in Pakistan