On November 15, 2020, an earthquake shook Corporate Pakistan, and absolutely nobody wanted to talk about it.

On that day Deloitte, the largest accounting and professional services firm in the world, and the biggest of the Big Four firms globally, left Pakistan. Search the newspapers for the next day, or frankly for several weeks after that, and you will find absolutely no announcement, no coverage, and no analysis.

But the silence does not change the facts. Yes, Deloitte was the smallest of the Big Four accounting firms in terms of its revenue share in Pakistan, but this is still a big deal. A very big deal. And it has considerable implications that will reverberate far beyond the world of accounting in Pakistan.

With Deloitte’s exit in November 2020, Pakistan is now the largest country by population – and the only one among the biggest ten countries in the world by population – to not have all Big Four accounting firms present inside the country.

Pakistan is the second-largest economy after heavily-sanctioned Iran to not have all Big Four accounting firms. The next largest economy to not have all Big Four is Ethiopia, which is about one-third the size of the Pakistani economy. There are economies in other parts of the world that are one-hundredth the size of Pakistan that still have all of the Big Four firms supporting their corporate sector.

This story will talk about why Deloitte left Pakistan, what that means for Pakistan’s accounting sector, and what it means for the wider economy.

What made Deloitte leave

Let us first specify exactly what happened. Each of the Big Four accounting firms – or really any of the major accounting firms – is a global network of partnership firms. What that means is that Deloitte in Pakistan is a partnership legally incorporated in Pakistan in which the global parent – Deloitte Touche Tomahatsu Ltd, the UK-registered entity – has no shares. Instead, it has a legal agreement that allows the Pakistan entity to use the Deloitte name in exchange for both monetary compensation and for agreeing to abide by a certain set of standards.

That partnership agreement – and specifically the right to use the Deloitte name and sign off with the Deloitte logo on its letters auditing Pakistani financial statements – is what has been taken away from the Pakistani partner firm.

When approached by Profit to comment on why they left Pakistan, the global parent company gave a statement that, while confirming the development, did not provide a significant amount of detail as to the reasons.

“We can confirm that as of 15 November 2020, Deloitte Yousuf Adil, Chartered Accountants (the Deloitte member firm in Pakistan) withdrew from the Deloitte network and is no longer a Deloitte member firm. The firm is now an Independent Correspondent Firm (“ICF”) to the Deloitte network, and its legal name has been changed to Yousuf Adil & Co. The decision to undertake this change was made in the backdrop of present geopolitical, macroeconomic, and market challenges,” wrote Lauren Mistretta, a spokesperson for Deloitte, in an e-mail to Profit.

We did not have any better luck in getting an explanation from the local former Deloitte partners either. “We have nothing further to add,” said Nadeem Yousuf Adil, chairman and partner at Yousuf Adil & Company, in a WhatsApp response to a question from Profit.

The only person from Deloitte willing to speak with us on-the-record was Asad Ali Shah, former managing partner of Deloitte Yousuf Adil, a position in which he served from February 2009 through May 2017. Shah is also the son of former Sindh Chief Minister Qaim Ali Shah. And Asad Ali Shah stated that he believed the main reason was a problem of economics: Deloitte’s presence in Pakistan created risk for the global partnership, but did not bring in a material enough amount of revenue to justify that kind of risk.

“The Big Four accounting firms don’t really get much out of Pakistan,” said Asad Ali Shah, in an interview with Profit. “The biggest firm in Pakistan is AF Ferguson (PricewaterhouseCoopers Pakistan) and they have approximately Rs3 billion in revenues, the bulk of which goes to the partners and the local staff. And what little does go to the global firm, they have issues remitting the profits because of permissions needed from the State Bank of Pakistan, etc.”

“The global firm makes money out of Pakistan in two ways: one, they help the local firm buy professional insurance against the risk associated with providing services. And secondly, they earn a management fee, which can be around 3% to 4% of revenue,” he said.

Even at 4% of revenue, that implies that the global partnership of PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), for example, would earn just about Rs120 million from Pakistan, which is just $800,000 at the current exchange rates. To place that in context, in the United States, which is the largest market for all of the Big Four firms, the average total compensation for a partner at PwC is $600,000.

About one-third of the revenue of any accounting firm goes to its partnership ranks, with the remainder paid out in salaries for the junior accountants, as well as other expenses. For a firm like PwC, with 30 or so partners in Pakistan, that comes out to a respectable Rs30-35 million per partner per year in revenue shares.

In short, the firms are set up to benefit the local partnership much more than the global parent company, and yet the global parent company bears all of the risk that the local partners bear as well. “The global company has 100% of the risk of Pakistan. If something goes wrong here with an audit, they will take a hit on their reputation,” said Asad Ali Shah.

You can see the problem here: all of the risk, and very little of the reward means that the Big Four accounting firms have a hard time justifying their presence in places where they see elevated risks. And the problem for Deloitte was that it had very little in revenue compared to the other firms.

“PwC is the biggest in Pakistan, with Rs3 billion in revenue. Ernst & Young (EY) is not far behind at roughly the same number. KPMG makes approximately Rs2 billion in revenue, and Deloitte was the smallest with just Rs900 million in revenue,” said Shah.

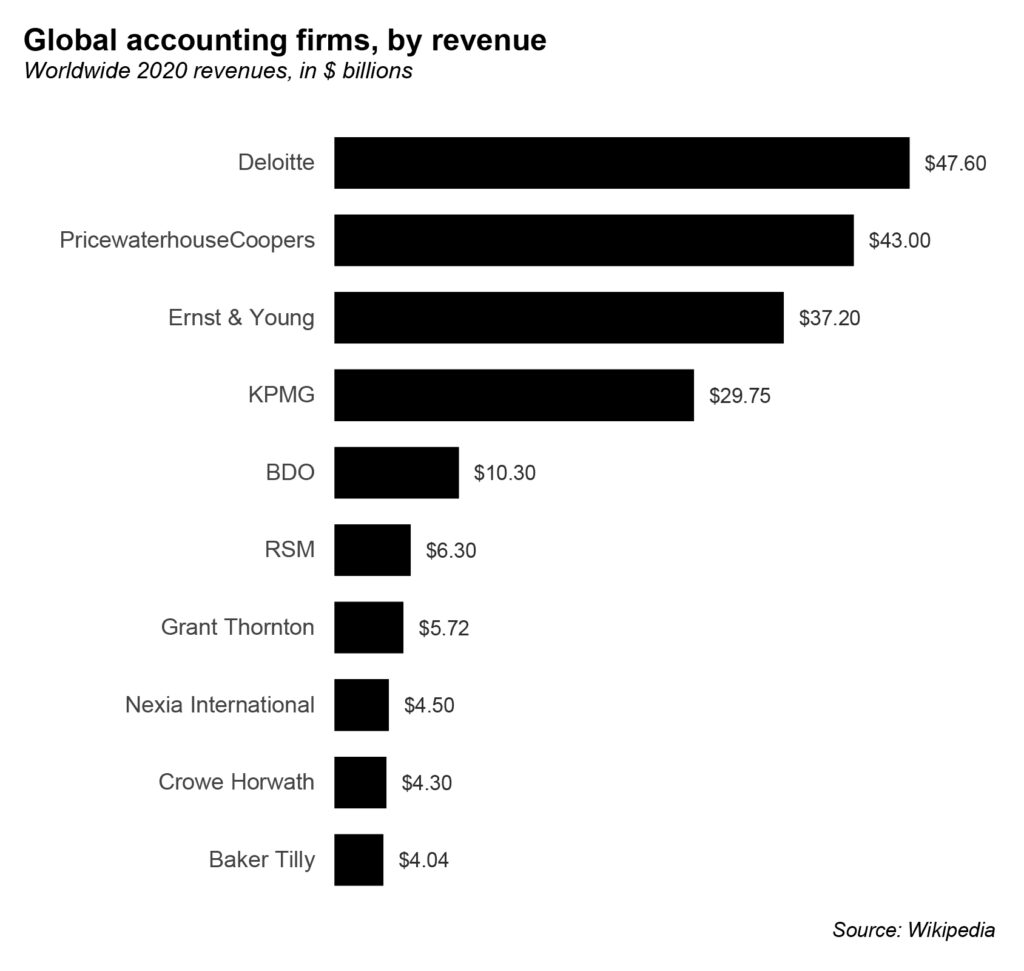

This, by the way, the opposite of its global standing. In 2020, Deloitte had a record-year worldwide, bringing in $47.6 billion in revenue. It is comfortably the largest accounting and professional services firm in the world. The second-largest in the world is PwC, with $43 billion in revenue. EY and KPMG are third and fourth respectively in terms of global revenues.

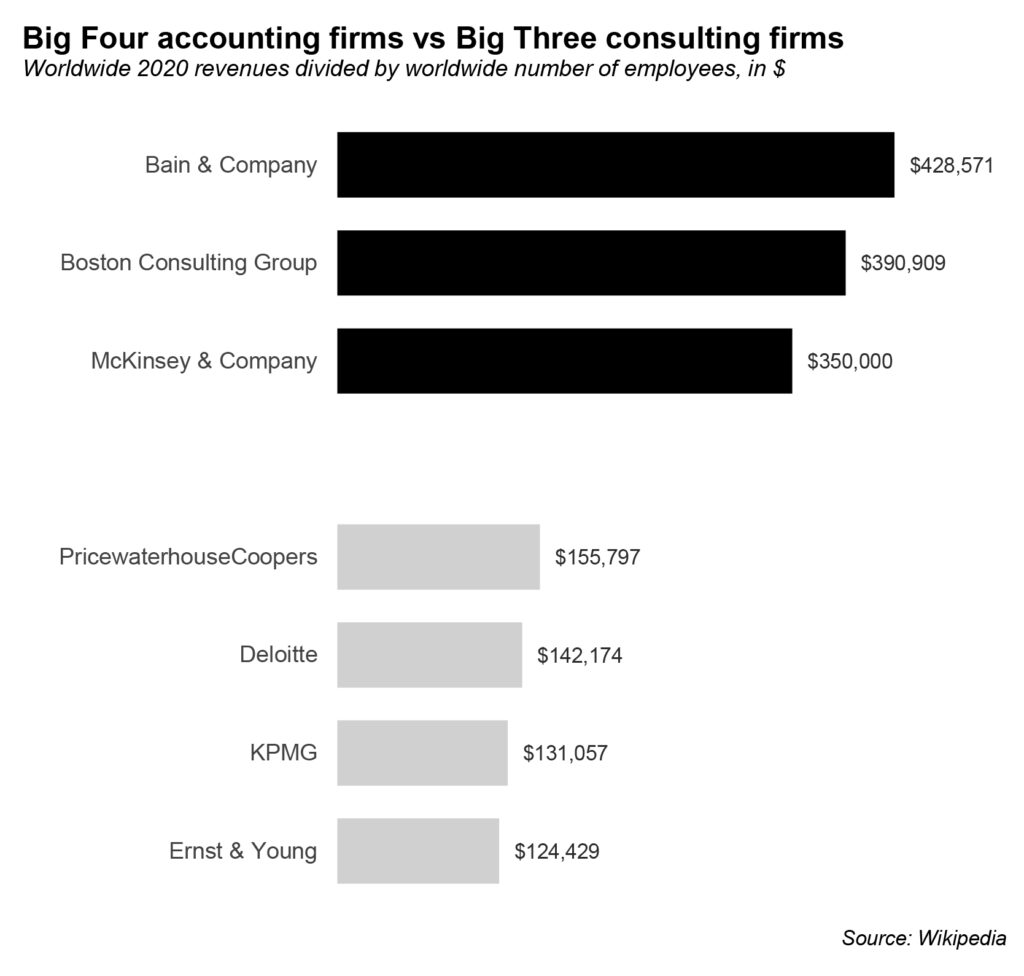

And that is the heart of the matter. Deloitte’s global partnership is used to making a lot of money in other markets, and in particular, they have a large presence in the high-margin management consulting business in the United States. By contrast, in Pakistan, not only do they have significantly lower revenues than their Big Four peers, but the bulk of those revenues come in the form of the low-margin audit and assurance business.

Then along came the increased pressure on Pakistan in the form of being grey-listed by the multilateral Financial Action Task Force (FATF) in 2018 for insufficient attempts by the country’s regulators and financial system to crack down on money laundering and terrorism financing, and the risk perception about Pakistan – already quite high – went up a lot.

What makes this development unfortunate is the fact that Deloitte Pakistan was actually among the most careful and conservatively managed of the Big Four accounting firms in the country and did not have any major scandals relating to its audit and assurance work with Pakistani companies that might taint its reputation, either locally or worldwide.

Deloitte left Pakistan because of the risk of what might happen rather than what actually did happen.

Incidentally, the weak financial incentives for Deloitte and the other major global accounting firms to lend their name to a local partner has resulted in a shift in the thinking of at least Deloitte, which wants to shift from the model of being a global network of partnerships to becoming much closer to a single global partnership that has a unified ownership, partnership, and management structure, in some ways closer to how management consulting rival McKinsey & Company operates.

What this means for Pakistan’s accounting industry

(Editor’s note: Feel free to skip this section if you could not care less which accounting firm gets to gain or lose from this development)

In order to understand what this means for Pakistan’s accounting industry, it is necessary to first take a quick look at the structure of the accounting profession, both in Pakistan as well as globally.

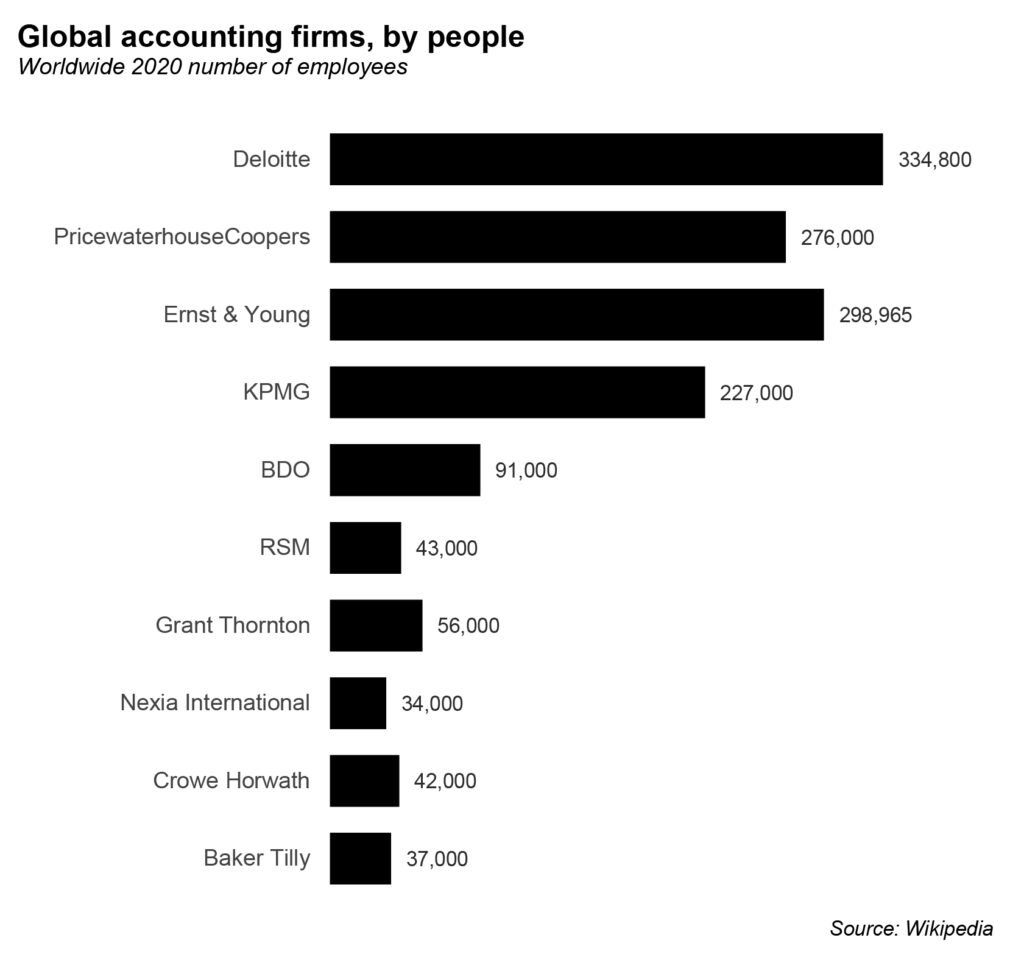

While there are thousands of accounting firms worldwide, the Big Four really do dominate. To understand just how much, consider the following fact. KPMG is the smallest of the Big Four and it is three times bigger in terms of revenue than the number five firm, BDO.

Why is that the case? Mainly history: the Big Four are the successors to some of the oldest accounting firms in the world. And it is a testament to just how much Britain dominated the world in the 19th century that three of the four firms are headquartered in London. (The fourth, KPMG, is headquartered in the Netherlands, the country that invented the stock exchange and the joint stock company.)

And it is because of their histories and big brand names that the Big Four command a certain cache with investors in companies that other accounting firms – for the most part – do not. Why do investor perceptions matter here? Because auditing financial statements of a company is the act of reviewing them for accuracy on behalf of the owners – that is, the investors – in a company. Hence, who investors trust to perform that role matters a great deal.

The Big Four are trusted more than other firms, and by more investors, which means that they get to command a higher fee than other firms. In Pakistan, in recent years, the price differential has grown incredibly steep. One of the authors of this story (Tirmizi) is the founder of a fintech startup, and was given two quotes by two accounting firms for auditing the startup. KPMG quoted a minimum fee of Rs1 million for the audit. Grant Thornton, the seventh largest accounting firm in the world, and the number five firm in Pakistan, quoted Rs250,000 in fees.

That is correct: the Big Four firm quoted a price four times higher than the number five firm.

Of course, that price tag does not exist in a vacuum. The Big Four can charge it because there are people willing to pay more for the ability to say that they are subjecting themselves to the rigours of an audit conducted by one of the Big Four firms, which is perceived to be better and more thorough than that of their smaller rivals. Is it actually more rigorous? The answer to that question does not matter as much as that the audit is perceived to be more rigorous, and to the point that people are willing to pay considerably more for it.

What this means is that the bulk of Deloitte Yousif Adil’s business was likely companies that wanted to do business with a Big Four accounting firm. What happens now that it has gone from being Deloitte Yousuf Adil to being simply Yousuf Adil & Company? How many of its clients will still want to continue doing business with the firm?

It is too early to say definitively, and the company declined to answer any of Profit’s questions. But the answer is likely to be that the firm will take a huge hit.

Yousuf Adil & Company will remain an independent correspondent firm with Deloitte, which means that it is authorized to provide services to Deloitte clients who have signed a global agreement with the firm and need services in a geography where Deloitte does not maintain a presence of its own. That means Yousuf Adil & Company will keep at least some portion of its clients.

However, many others will likely decide that they would rather work with one of the other Big Four firms than one that is simply a ‘correspondent’ firm.

But here is the punchline: it will likely struggle to get new clients.

Why? Think about it from a company’s perspective. If you have enough cash and can afford a Big Four audit fee, why would you go with Yousuf Adil & Company rather than one of the other three that still do business in Pakistan? And – assuming you were one of those companies that did business with Deloitte Pakistan because you had an old deal for a low audit fee that was still going, would you rather stay with a local firm that used to be a Big Four, or would you rather just cut your costs and go to the number five firm?

Because, let us be honest: yes, the Big Four have the best-known brand names, but any investor worth their salt also knows of Grant Thornton and BDO. If you have financial statements signed with the logos of either of those firms, you know that any investor you present them to will have a reasonable amount of confidence in them. But take an audit report with the “Yousuf Adil & Company” letterhead, and you might get asked a few questions about why you chose this particular auditor, which some foreign investors especially may have never heard of.

All of this is to say that Deloitte’s loss is likely to be Grant Thornton and BDO’s gain. Both firms have a significant presence in Pakistan (as does every single one of the other top 10 accounting firms in the world) and are likely to be well positioned to pick up clients.

Indeed, it is also possible that some of the Yousuf Adil & Company partners will decide to take their relationships to either of these two firms – or any of the other Big Four that will have them – rather than trying to remain independent without the Deloitte brand to back them up.

And lest you think this is pure speculation on our part, there is some precedent for what we are talking about. In 2002, there used to be the Big Five accounting firms, with the Chicago-based Arthur Anderson being the fifth global accounting firm. When Arthur Anderson imploded in the aftermath of the Enron scandal – after it emerged that they had signed off on fraudulent financial statements from Enron – Arthur Anderson’s Pakistan affiliate began to face problems retaining clients.

That affiliate with Sidat Hyder, which almost instantly began to lose clients. In June 2002, Dawn reported that Singer Pakistan had dropped Sidat Hyder and instead appointed KPMG Taseer Hadi as their auditors. By the following month, the situation had grown so bad that Sidat Hyder decided to merge with the EY member firm in Pakistan: Ford Rhodes Robson Morrow. That is why the EY member firm in Pakistan is still called Ford Rhodes Sidat Hyder.

What that tells you is that an accounting firm’s brand and credibility matter a great deal, and that its fortunes can change overnight if the perception of that brand changes.

What the Deloitte exit means for Pakistan

Why should you care about Deloitte leaving Pakistan if you are not an accountant, or a CFO looking to hire an audit firm? Because it represents a fraying of Pakistan’s international reputation to a point from which it may be difficult to recover unless the government and the corporate sector decide to take drastic action.

It is, in no uncertain terms, a national embarrassment that Pakistan is now the largest country in the world – and the largest non-sanctioned economy in the world – that does not have the presence of all of the Big Four accounting firms.

But even beyond the embarrassment of it all, there are practical implications for the Pakistani economy, and most specifically for foreign direct investment into the country. Investors look first and foremost on accurate, reliable information sources that they can trust about the country and companies they are about to invest in. And the departure of Deloitte means there is one less credible voice that they will trust that might be telling them that it is okay to invest money into Pakistan.

If you are a company in Pakistan that wants to have a global set of investors from whom it is looking to raise capital, if you are a startup that is looking to raise money from global venture capital funds, there are now fewer accounting firms that you can put on your financial statements that would give those investors the comfort that you are telling the truth about the financial health of your company.

Credibility, more than anything else in the world of business, matters, and Pakistan just lost a significant source of it.

Of course, we should also not exaggerate the effects. This is one of four firms, and the other three are still here. But Deloitte’s departure is a warning and a bad precedent, particularly in light of reports that Ernst & Young is actively evaluating whether or not they want to stay in Pakistan.

The situation at Deloitte and EY are completely unrelated. But the fact that both are happening at the same time – and that Deloitte decided to pull the plug – means that Corporate Pakistan’s international credibility is about to be put into question right when startups are expanding the definition of what it means to be a Pakistani company and finally beginning to attract serious volumes of money into the country.

At least with Deloitte, there is the reasonable explanation that they had a low market share and that there were clearly no scandals or problems that were covered up.

What will we tell ourselves and foreign investors if EY decides to leave? They have the second largest market share in the audit market in Pakistan, only narrowly behind PwC. That would be tantamount to saying: Pakistani companies and entrepreneurs cannot be trusted to tell the truth, their auditors cannot be trusted to verify their statements on behalf of investors and there is no hope that the regulator will fix the situation anytime soon.

If that were to happen, we would find ourselves struggling to attract even the meager levels of foreign investment that flow into the country right now. And in as capital-starved an economy as ours, that is a luxury we can ill-afford.

(Editor’s note: Despite repeated reminders, Asim Siddiqui, country managing partner EY Ford Rhodes, Pakistan did not respond to the questions emailed to him by Profit. However, after the publication of this story an industry insider told Profit that the threat of EY exiting from Pakistan was constantly looming for the last year and a half, but recently they agreed on an operating protocol due to which there is no immediate threat)

One bright side for Pakistan is that big four were in it’s boundaries but why we proud for foreign affiliation rather to make ourselves a brand.

Any concern person explain it.?

There is no such thing as pride when it comes to the economy of a country. The moment we base our economic decisions on rational and economic viability rather than useless rhetorics and emotions, we will start progressing.

It’s not about being proud for foreign affiliations. Global firms like Deloitte considerably improve local industry by bringing in top-class expertise and best practises. In this case, they partnered with Yousaf Adil & Co, benefiting a Pakistani company and giving them global exposure, but now no one will recognize this firm without Deloitte affliliation. As the article points out that only Iran and Ethiopia don’t have these big 4 accounting firms and now Pakistan has joined this”elite” club. Do we want to benchmark these countries or the developed countries in the world? Look at our neighbour India, almost every medium to large scale global company of every sector is present there and enormously benefiting their economy. Their pride doesn’t get hurt by this or does it?

Really great article. In the end it’s all business.

Big FOUR have their maladies of BIG FINES ?

A big question raises on Corporate Governance structure in Pakistan, along with ICAP policies as well where Firms/ partners are required to be rotated. Those ho can afford big3 would be rotating among the same thus a similar chances of collusion may take place like Japanese companies scandals are reported like Toshiba and others, where would the shareholder go?

Deloitte is an anagram for toiletteD.

While disappointing that this happened – when regulatory standards of compliance are significantly relaxed relative to more developed countries where the Big 4 operate – it creates an economic vacuum which is filled by smaller firms that do not have to adhere to same standards and have a lower cost base. Relationships with clients are transactional rather than strategic/value driven in most cases. The conjoint impact of this would not allow economic survival of firms that incur costs to ensure standards over and above minimum compliance requirements are met – I personally feel that more of the Big 4 names will find the exit route as a natural and viable commercial outcome.

In November 2020, Deloitte left Pakistan. So Pakistan don’t have BIG 4 firms right now.

That’s very sad news.

The reason of departure from Pakistan is lack of good customers and pretty less revenue.

And It doesn’t stop here. EY is also thinking about either to leave or stay in Pakistan.

Almost all Big Firms get nothing from Pakistan.

Can anyone please explain that will Deloitte return in Pakistan?? Any possibility??

Has Deloitte permanently departed Pakistan??

This whole article is a lie. The correspondent is clearly saying that Yousef Adil is not Deloitte partners in Pakistan. She said NOTHING about pulling all of its operations from the country. On Deloitte website, you can still see Pakistan as one of its locations.

The timing of Shah’s departure & Deloitte’s exit raises many questions. Infact it was the Shah who brought DTT here after it’s first exit from Pakistan leaving KMHR in limbo & ultimately merged. The fate of Yousuf Adil seems same.

what is a beam bridge used for