It was a simple problem with a simple solution. For decades now Pakistan has been home to the unique problem of ‘Doctor Brides’. Women make up the majority of medical students in Pakistan. In fact, in medical colleges spread across the country, around 70% of those attending are women.

Yet only around 23% of these women end up practising because many either drop out in their final years or opt not to practise medicine after getting married.

It is a persistent social issue that causes intense debate and has been linked to Pakistan’s abysmal doctor-to-patient ratio. With a total medical workforce of over 2 lakh doctors, there is only one doctor available for every 1200 patients. The conspicuous absence of these qualified and talented women doctors from the medical workforce is a sore spot within the medical community. The other sore point for the healthcare system overall is that the marginalised communities are the most deprived of quality healthcare.

Dr Sara Saeed was one such ‘Doctor Bride’. After graduating from medical school in 2010 Saeed married and her medical degree sat collecting dust. Throughout this time as she navigated married life and motherhood there remained an itch in her to use her education not just to help patients in need, but also other women doctors like her whose careers were cut short by social expectations and pressures.

Today she runs Sehat Kahani. This is a telehealth startup that connects doctors to patients on a single platform for basic, online consultations. The idea was that the startup would give the opportunity to female doctors like Sara herself to practise from the comfort of their homes while also giving users access to qualified doctors at the click of a button.

Around three weeks ago Sehat Kahani announced a $2.7 million Series A funding round at a time when startups are finding it increasingly difficult to find money. The round is the largest for a telehealth startup and underscores the market leadership that Sehat Kahani has found in this segment. Over the past few years Sehat Kahani led by Dr Saeed has won multiple prestigious awards and grants that have propelled Sehat Kahani in its journey.

But the story is not so simple. Behind the scenes of Sehat Kahani is a complicated reality. The telehealth segment is over-saturated with competitors trying to make it work one way or the other, customers are hesitant to trust (and pay for) online consultations, and the entire industry’s business model is still a work in progress. As a consequence, the inflow of VC funding has been slow. Not only is the competition stiff in a developing industry, there is also bad-blood within the competitors.

So how did Dr Sara Saeed manage to take Sehat Kahani in such an environment and bring it to the forefront of this industry? To understand the story we must go back to where Dr Saeed first got into the telehealth business. Because Sehat Kahani is not the first telehealth startup in Pakistan. And it is also not Dr Saeed’s first startup.

The doctHER brides

In 2007 Dr Asher Hassan setup Naya Jeevan — a social enterprise that would provide low-income workers in the corporate world with affordable healthcare through insurance. Now this is important to understand. Naya Jeevan was the entity set up by Dr Asher and its goal was providing healthcare solutions to corporations for their low-income workers.

It was for this company that Dr Hassan hired Dr Sara Saeed in 2012. The two doctors worked closely and Hassan learned about how his new employee was one of many doctors in her batch that did not practice after graduating from med-school because they got married. By 2015 the idea of doctHERs was conceived. This was supposed to be a platform to connect the at-home female doctors to patients in low income communities. Dr Sara served as the first female doctor of the platform who served patients in the first e-health clinic in the Sultanabad area of Karachi. The project was incubated under Naya Jeevan with Dr Asher as the cofounder, CEO and chairman of the new business that was later spun off as a separate entity.

The other co-founders of the business included Dr Sara Saeed and Dr Iffat Zafar Agha, who were both given equity in the new venture and served as its chief operating officer and chief development officer, respectively.

The startup immediately started making some noise. The best startup ideas are the ones that solve very specific problems. And doctHERs was trying to wrangle an incredibly unique issue that had not just vast local application, but was bound to drum up some international attention. In 2016, the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) launched the Global Goal Awards to honour individuals and companies for their contributions towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. One of the initial winners of this award, announced in September 2016, was doctHERs which was recognized for contributing towards the goal of improving the lives of girls and women by connecting female doctors to vulnerable girls and women via telemedicine. At UNICEF, doctHERs were represented by none other than Dr Sara Saeed — the face of the company.

Fault lines appear

There is an eerie silence regarding what exactly happened from this point onwards. All we do know is that after the UNICEF award doctHERs focused on gaining more and more grants to keep running. As part of this, Dr Saeed took the lead in looking for such opportunities and was very much the person running the show at doctHERs. What we do know is that in the process of finding these grants there was a fallout between the founders of doctHERs.

According to one side of the story there was a serious disagreement following a USAID grant application that was being implemented by Dr Sara Saeed and Dr Iffat Zafar. In any case, doctHERs was soon demerged. As this split continued to grow Dr Saeed and Dr Zafar took centre stage. Even though he was the original founder of Naya Jeevan, Dr Asher Hassan had already left a lot up to these two. On top of this, Dr Saeed and Dr Zafar had themselves been ‘Doctor Brides’ before they helped create doctHERs. This meant that as far as marketing was concerned they had an edge over Dr Hassan.

By 2017 the split had been finalised and doctHERs was demerged into two entities, the other one being Sehat Kahani. Following the demerger in March 2017, Dr Sara had then said that all matters were amicably settled between all three founders to demerge operation in a manner that all existing clinical operations, tangible assets, contracts, MoUs etc. are transferred to newly formed venture Sehat Kahani.

What is interesting however is that Sehat Kahani seems to have gotten a pretty sweet deal out of the split. It was decided that Sehat Kahani would execute all “existing contracts/partnerships” until their expiry. Whereas doctHERs will be strategically pivoting to focus on the corporate sector and corporate value chains (factory workers, suppliers, distributors, retailers, micro-retailers, etc) and will continue to expand its nationwide network of remotely located female doctors.

Sehat Kahani has refused to give any details about its demerger with doctHERs, the reason for the demerger and detailed terms of the settlement saying they were in a litigation with doctHERs. Likewise, Dr Asher also said that because of a litigation with Sehat Kahani, he couldn’t comment.

Sehat Kahani takes flight

There has been no looking back for Sehat Kahani since the demerger with doctHERs. Not only does Sehat Kahani have a unique mission it has managed to present itself well to investors. The startup has raised $500,000 in its initial round, $1 million in pre-Series A funding and recently managed to get a $2.7 million Series-A round, making it the best funded telehealth startup in Pakistan. Its roster of investors include Pakistan’s Elahi Group of Companies, Din Group, 10Pearls Ventures, Islamic Development Fund, Mentors Fund, Epic Angels and Cross Fund among others. But perhaps even more than funding from investors Sehat Kahani has also focused on donations and grants.

And once again, we’d like to repeat that Sehat Kahani is presumed to be the leader in the telehealth space. While others are struggling, Sehat Kahani is soaring.

The idea of telehealth in a country like Pakistan makes sense. It is a business-to-consumer as well as a business-to-business model in which a platform directly connects doctors with patients. Because of crumbling healthcare infrastructure people require doctors for basic consultations and there is a ready crop of doctors available to provide this service online in the shape of these many unutilised women doctors.

Yet there is a major problem in this business model. As one source in the industry explains to Profit, given the size of Pakistan’s population, 99.99% of the people still prefer physical consultations, even though the uptake of digital has increased but as a percentage of the size of the population, it would be the remaining minute 0.01% that is digital.

This is because consumers are not yet willing to pay for a doctor that they can not physically visit at a clinic or a hospital and hence not yet monetizable in a silo. Consumers would, however, be willing to adopt online consultations if they are able to get all or most of the services in the primary healthcare continuum. That is to say a consumer would be unwilling to go online to see a doctor for primary healthcare services if it is only a consultation with a doctor, but they would be more inclined to use digital as a mode of healthcare if they are also able to order medicines and lab tests along with the video consultation.

Pakistan’s telehealth business is small with only a handful of players in the market, struggling and fledgling around. The list includes names such as doctHERs, Ailaaj, Oladoc and Sehat Kahani, most of which started with teleconsultations or medicine delivery but have now either consolidated or are trying to consolidate all the services together with teleconsultation, to make their platforms monetizable. Some of these have raised venture capital rounds but smaller ones, which attests to the inability to scale very quickly in Pakistan despite the very large size of the population.

For instance, OlaDoc raised $1.8 million in their pre-Series round over a year ago. Ailaaj raised $1.6 million in a pre-Series round over two years ago. There is no public announcement from doctHERs of any funding, while MedIQ has announced a $1.8 million raise in April 2022. Sehat Kahani is the only recent one to have raised a $2.7 million funding round. Why are the rounds not being raised very frequently and why are they not so big? Because there is not enough growth of consumers yet, and there is not enough ability to monetize those consumers. It is going to take a while where it becomes workable at scale, as a source said.

What you need ideally is an integrated business model. The model we are talking about is the business to consumer model where through an app, the telehealth companies would reach out to a target market virtually of 230-240 million people, which is the entire size of the Pakistani population because everyone is going to get sick and everyone is going to need to see a doctor. While growth could not come from the B2C segment, the telehealth companies have been looking at other avenues of getting revenue and some even using the teleconsultation business as a means to generate business from other business lines.

Oladoc, for instance, which only used to be an aggregator for doctor appointments, has recently ventured into directly providing telemedicine services, but does not expect to generate profits from this business. Instead, for Oladoc, telemedicine would be a loss leader for the business. That is to say telemedicine would bring customers to the Oladoc platform but it doesn’t expect to make money from this business. Instead, it will convert those customers into ones that would now book physical appointments with doctors at the Oladoc platform, from where it actually thinks it can make money.

On the other hand, some of the telehealth startups in Pakistan provide telemedicine services to employees of corporations, either directly or through insurance companies. This segment, otherwise called B2B, is also riddled with problems. The corporate target market is small and there are more competitors than there should be to cater to this market, decreasing prices for everyone and turning losses. In the words of a source familiar with the telehealth business in Pakistan, “targeting corporations for telehealth business in Pakistan is a race to the bottom because of the presence of so many companies in this segment.”

Then there is an issue of low level of utilization in corporations. Utilization is to say how many employees use a telehealth platform for virtual consultations. If the utilization is low, people in a corporation that have subscribed to such service are not using it actively. Our source claimed that utilization in corporations is less than 5%. On the other hand, the current model also leads to higher losses in case the utilization increases, according to the source.

Sehat Kahani claims to have a utilization rate of as high as 40%. The corporate model, otherwise called B2B model, in Pakistan is also presumed to be unworkable in its current state and more so in the presence of increasing competition.

The B2B is not a very big market to begin with. If a high value startup is to be produced in the telehealth space, B2C needs to be adopted at a bigger scale and people need to pay for it too. According to a source, the current unit economics of the B2C model for it to make sense as a business looks something like this: about 50% goes to the doctor providing the consultation on the platform, 20-25% is operating cost and 20-25% is profit. Why do we think so? Just take a look at Sehat Kahani’s financial performance which corroborates with this thesis.

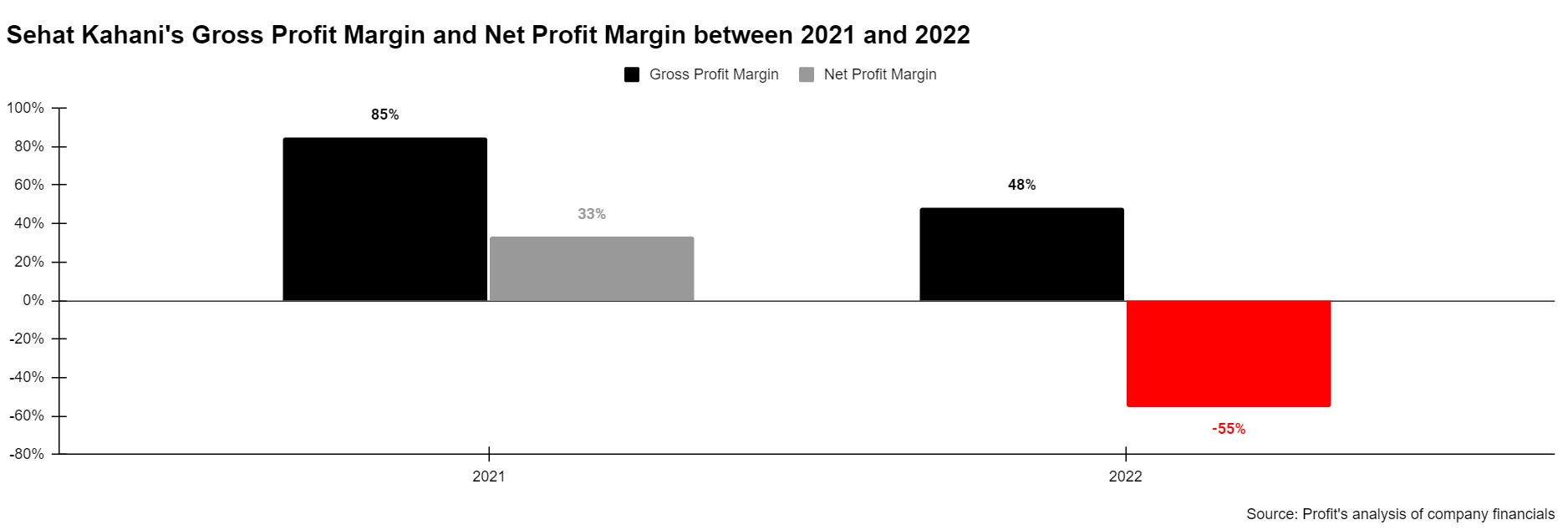

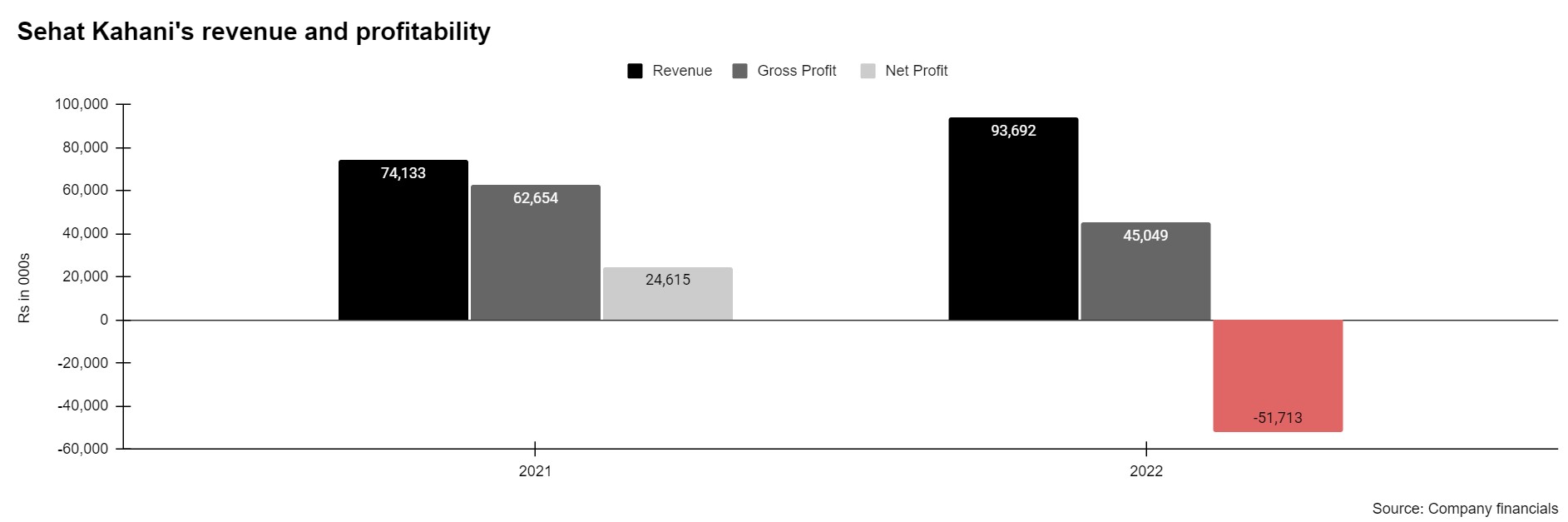

For the financial year 2021, the company booked a small revenue of Rs 7.4 crore and incurred a net profit of Rs 2.4 crore (why was it a net profit and not a loss comes below). For the year 2022, Sehat Kahani’s revenue swelled to Rs 9.36 crore, still a small amount, but incurred a net loss of Rs 5.1 crore.

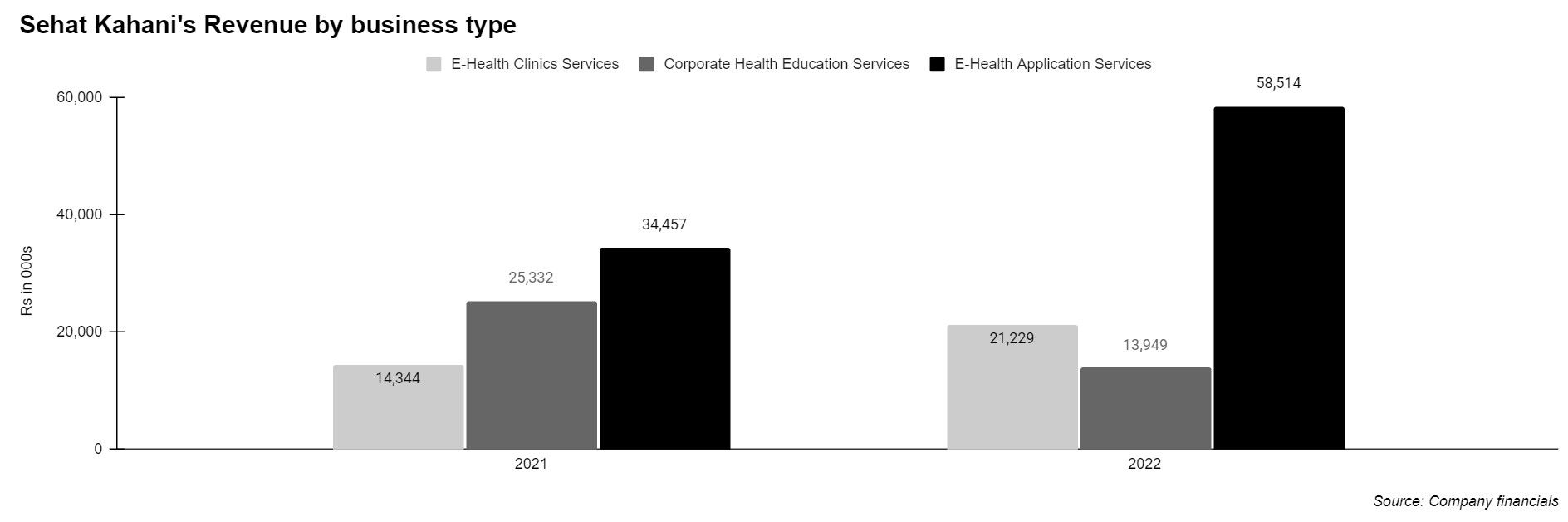

And this is the company that is raising the best rounds and is the most prominent in the telehealth sectors. The company earns revenues from three sources: the e-health application given to both retail and corporate customers, e-health clinics which is assisted telemedicine through a physical clinic [think EasyPaisa and JazzCash agents but for telehealth], and B2B health education services which is the tiniest of them all. Profit has not been able to get details about B2B health education services.

None of the above should imply that telehealth is not workable in Pakistan. It is just that telehealth models currently in place are not working as they should and everyone is trying to come up with best strategies to make them work. The potential here is big but there is an uphill battle that needs to be fought first and for sometime.

If you can’t find investors where do you go?

All of this means that getting outside investors becomes a problem. There is not enough growth and there is not enough profits, which is a prerequisite for raising funds in the ongoing funding winter. Hence the infrequent and small rounds. On the other hand, cash burn is high due to the costs associated with the business and the spend required on marketing to bring the growth numbers.

So what do you do if you are a business that can not access enough VC money to plug cash flow issues?The answer is you turn to free money or non-dilutive capital. That is what Sehat Kahani did and it did it on the back of being a social enterprise with benefits for the health of the society. It turned towards securing that free money from donations and in the shape of grants. Donations are monetary gifts given in pursuit of a cause someone believes in, while grants are funds given to organisations to attain a certain goal with KPIs to be achieved but are not intended to be paid back.

It has won donations and grants and it has also been able to win some high profile awards such as the Rolex Awards and Cartier Awards, both of which come with hefty prize money that would have played an instrumental role in growing the company to the point that it was able to raise venture capital funding and reduce reliance on prize money, grants and donations.

This is actually a very interesting approach. One of the harsh realities of the startup world is that founders start their journeys with an idea that people want to be part of and find themselves spending less and less time on the idea and more on convincing investors so they can scale their idea. The reliance on investors continues to grow and the results are less than ideal.

So finding streams of revenue for a startup that aren’t equity funding is always a bonus. After all, there is no money that is better than free money.

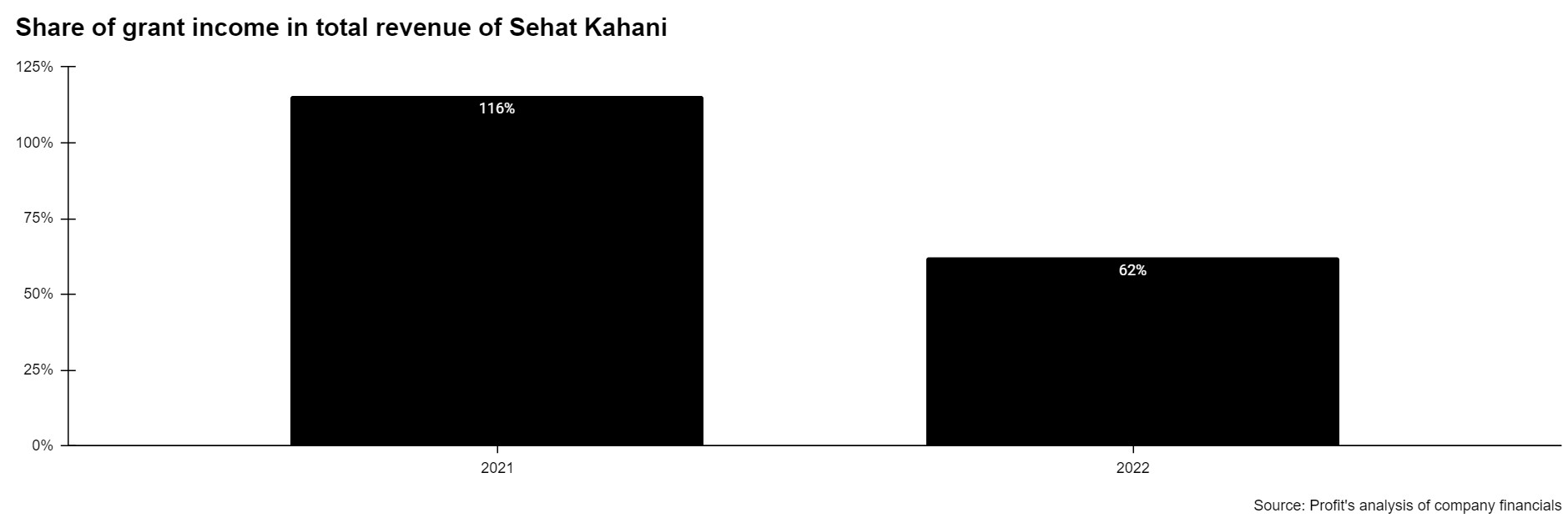

Sehat Kahani’s losses for the year 2022 would have been much bigger and net profit for the year 2021 would have been a net loss hadn’t it been for the sizable grants that the company reported in the other income section of its financial statements.

For the year ending June 30, 2021, the company reported having earned a grant income of Rs 85.7 million, bigger than the revenue from core business, and received Rs 2.7 million in donations. For the year ending on June 30, 2022, the grant income received by the company was Rs58.2 million and donations received were Rs 1.2 million.

Sehat Kahani’s recent Series-A round of $2.7 million also hosts investors that are not VCs. USAID for instance is not an investor but a donor organisation that gives money to organisations to achieve certain goals and monitors the progress of these goals, but does not take equity in the company or asks for the grant to be paid back unless the criteria set by the organisation is not met. Sehat Kahani has not yet disclosed, in question asked by Profit, what proportion of the recent round was equity-based, how much was debt and how much was grant money.

This is actually a very smart way to fund an organisation that is passionate about creating a successful business but can not do so because of the state of the market that doesn’t allow much monetization. Sehat Kahani is a good story to tell and has a founder that knows how to present it well. Pakistan is an underdeveloped economy, the western society and some of the local businesses care about healthcare and are ready to give money to social causes that also empowers women. It is the kind of pitch organisations would lap right up.

Consequently, Dr Sara Saeed has been able to win some high profile awards from, for example, Rolex, known for the prestige of the brand, as part of their ESG (environment, sustainability and governance) program. The winners get up to 200,000 Swiss Francs in prize money, which in today’s time is over $250,000. The award also comes with international publicity through Rolex (and a Rolex gold chronometer watch to boot). Dr Sara Saeed won the Rolex Award in 2019.

These awards are a great way to funnel money into a business. They not only come with money, but also with prestige. They can seriously elevate the profile of the candidate so that next time winning is not difficult. And as you might expect, Sehat Kahani is not the only organisation looking to capitalise on these awards and grants. Their competitors too want a slice of the pie. The only problem is when some of the achievements of the founders applying are mixed together.

Take for example the $30,000 Cartier Initiative Award that Dr Saeed and Sehat Kahani won in 2018. The award was supposed to be for a business that was creating impact and was an original idea. Cartier’s own rules of participation for the Women’s Initiative Award say that the idea must be original and not a copy of some other business. While Sehat Kahani is an impactful business driven to the cause of improving lives through healthcare, it is not exactly an original idea. After all, doctHERs was the original company trying to solve this problem. The issue is that Dr Saeed was a co-founder in that company as well. In media interviews, however, Dr Sara has admitted that doctHERs was Dr Asher’s idea and did not take credit of the company for herself.

According to a source, due diligence is sometimes surprisingly lax at some of these awards. “Winning awards is a big business. All you need is a good story. And these awards are foreign so they can not carry out thorough due diligence much like VC funds who tend to believe what is told to them. And much like VCs, these awarders also believe that if an award has been won earlier and that the awarder is a prestigious entity, that awarder would have done the due diligence before giving the award.”

That is to say that if UNICEF gave doctHERs the first award and Dr Sara and Dr Iffat Zafar were the cofounders, the new organisation such as Rolex or Cartier would believe that UNICEF would have done its due diligence before giving the award, making them comfortable to hand out the award without doing a thorough due diligence on their own. Later in 2020, Dr Iffat Zafar Agha also won the Elevate Foundation Prize award which comes with an award money of up to $300,000.

The product itself

So here we have a unique startup that has found a market perhaps not quite ready for its product. It has instead of wilting found a unique solution and has marketed itself well. But how exactly does the product measure up?

At the centre of this murky situation was once Sehat Kahani’s mobile application. Launched in 2019, after a very short operational duration, the app still has a clunky interface with the saving grace that it works. As a ‘for-profit’ social impact enterprise, as Sara likes to call it, providing healthcare services to marginalised communities the application was always going to be a topic of conversation.

As it stands, Sehat Kahani’s claims to have a network of 7,000 doctors that it works with. That is to say about 7,000 doctors could potentially provide healthcare services to patients through the Sehat Kahani application. But when it was launched, it had doctors, most of whom simply had an MBBS degree. The problem was that a lot of them were listed as having certain specialities. Now remember, they did not at any point say a certain doctor had completed a specialisation but rather they were “good” at certain things.

Since the app is meant for primary care, it is known that the doctors will all be GPs, and it will be their duty to forward the case to a specialist if it comes to it. Nowhere on the app was it claimed that the doctors have a degree that they do not have. But was this just a clever misrepresentation? Or was Sehat Kahani luring patients by using the word ‘specialist’ irresponsibly?

Dr Sara’s response then to Profit to the accusations was in the form of indignation and refutation but soon after the interview with Profit, the platform resolved the issue, by removing specialisations of doctors and decreasing rates on these consultations.

One might say that a doctor claiming expertise is simply giving the patient more trust in themselves, especially at the primary level, but doctors masquerading as specialists can actually put a patient’s life in danger.

“It is an unethical practice that can endanger a patient’s life,” a Lahore-based psychiatrist had said, affirming the dangers of such practice. “And not only that, it also undermines the status of a qualified specialist, who, being a specialist, actually understands the subtleties associated with the profession”, he had said.

What is ahead for Sehat Kahani?

For now the company has managed to not just ingeniously get through the funding crunch, they have also found ways to keep their operations funded by maintaining and promoting their brand image and keep the grant money coming in. And after going through these initial birthing pains, it has now been able to secure a sizeable VC funding. This means they will now be able to acquire customers, and grow further, even if that means running more losses. This could in turn lead to a higher valuation.

They also plan to go global, with plans to scale in the UAE and Saudi Arabia in the next 12-18 months. While it continues expansion, the company also says they would be focusing on profitability and would become profitable by 2025-26. Up until now Sehat Kahani has managed to keep going with the help of grants and awards, building an impressive profile for itself. But if it has any hopes of going the distance it must now look towards convincing investors to put in the money. And to do that, Dr Sara Saeed and the Sehat Kahani team must look towards their business fundamentals. Currently, the startup looks like in a high-growth mode with free and discounted consultations being offered by the company.

At the same time, the ethical questions around the business pose a bigger concern, which is concern for the welfare of the patients they serve. Unlike a grocery delivery or a mobility startup, high-growth or hyper-growth ambitions and valuation play, which is what VCs usually seek, on customers’ health could turn out to be counterproductive not just for Sehat Kahani but for all other telehealth companies. If things go awry, it will ruin the trust in telemedicine altogether.

MY PERSONAL EXPERIENCE ON LOST CRYPTO RECOVERY!

I read so many stories about bitcoin loss to scams. I will like to start by saying the agencies responsible for bitcoin security has really done nothing to help locate stolen or lost coins. In my situation my MacBook was hacked by someone that had access to my emails, i immediately contacted blockchain and they only wasted my time, after which i worked towards getting help else where, i was referred to consult a bitcoin expert who helped track and retrieved my 3.3 btc, for an agreed fee. I was more than grateful and willing to pay more after the job was done. Thankful i didn’t fall victim and would like to recommend ( MORRIS GRAY 830 @ G maiL . COM )

it was and still is a wonderful idea, no doubts there but unfortunately the telemedicine platforms are more focused on business and numbers instead of an actual impact. Telemedicine in Pakistan is an opportunity for responsible businesses only but I’m afraid as the time will pass due to unethical and business focused practices, it will lose its remaining worth when people will lose confidence in the product itself.

It’s important to understand that the number of downloads is not success, the number of 3rd, 4th, 5th … etc… consultations out of that pool is actually the success.

Let’s hope responsible businesses are able to make the importance of telemedicine known!

The Good think Sehat kahani. Health is most important things to humanity.