In its recent report released in May 2024, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has raised a significant alarm regarding Pakistan’s microfinance sector, pointing out ‘persistent vulnerabilities’ in its recent report.This concern is not new; the sector has been grappling with severe challenges for a couple of years.

This has been the case for a few years now. In 2022, Profit did a story on the microfinance sector’s dire state describing it as a “time bomb” ready to explode.

Read: Microfinance Banks on the verge of crisis

The primary issue threatening the equity of these microfinance banks was the high risk of loan defaults, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. This crisis is far from resolved, with the situation in 2024 remaining just as precarious.

Despite efforts by the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) and the government to provide relief and stabilize the sector, the outlook remains bleak. The sector’s current state prompts a crucial examination of its performance and the key players involved.

Key players in Pakistan’s Microfinance Sector

The main investors in the country’s microfinance banks (MFBs) are commercial banks, telcos, nonprofit entities/rural support programmes and specialised microfinance institutes.

The NGO-backed MFBs include the likes of NRSP Microfinance Bank Ltd, a subsidiary of the National Rural Support Programme, the Kashf Foundation as well as the Aga Khan Foundation’s philanthropy wing. The investments are an extension of the vision of these organisations; a vision based on poverty alleviation through financial inclusion.

The telcos adventure in the sector started after the SBP authorised the issuance of branchless banking licences in 2008. Telenor was the first one to do this when it joined hands with Tameer Microfinance Bank to launch Easypaisa in 2009. Jazz followed them closely by launching Jazzcash in 2012. The telcos soon bought the majority stakes in these banks and rebranded them. Tameer became Telenor Microfinance Bank, Waseela was converted to Mobilink Microfinance Bank Limited (MMBL) while Rozgar Microfinance Bank was renamed U Microfinance Bank Ltd, more commonly known as Ubank, after acquisition by the PTCL.

Commercial banks are also key players in the sector. The likes of HBL Microfinance Bank Ltd and Khushali Microfinance Bank Ltd which are subsidiaries of commercial banks, with United Bank Limited (UBL) holding a 30% stake in Khushhali and Habib Bank Limited (HBL) holding over 70% in HBL Microfinance Bank.

Overall, there are about 11-12 players in the industry. Out of these, there are five that dominate the scene. These include the three telco

Impact of COVID-19

You see when the pandemic came about, lockdowns halted business activity. Microfinance institutions provide small loans to a target audience that is not the most affluent in society. These are loans that could be provided to someone to open a shop for their trade such as to a barber or a carpenter. Unfortunately, these were exactly the people most impacted by the lockdowns with their small businesses being closed for months on end. This meant the microfinance sector was caught in a fix as the majority of its borrowers were not in a position to pay their loan instalments immediately.

The regulators realised that a crisis was brewing. To try and stave off the rot that was setting in, the SBP decided to ease the pressure through the Debt Relief Scheme for deferment or rescheduling of COVID-affected borrowers through BPRD Circular No.14 of 2020. As per the scheme, the payment of loan principal could be deferred for up to 12 months if the borrower continues to service the interest amount. The scheme also provided a restructuring option through which the outstanding principal and interest could be converted into a new loan altogether with revised terms and conditions. The programme remained valid up to 31 March 2021.

Though the relief was for the whole financial sector, the microfinance entities were the primary beneficiaries. “Since the launch of the scheme, individual borrowers, especially customers of microfinance banks, have been the major beneficiaries of the scheme. The restructured and deferred loans include 1.717 million approved applications of customers of microfinance banks involving an amount of Rs 121 billion, which approximately constitutes 50 percent of total net-loan portfolio of MFBs,” stated SBP website.

However, once the scheme expired in 2021, the sector started facing a fallout in the form of a deterioration of portfolio quality. Yet, it must be noted that this wasn’t something the sector didn’t anticipate in the first place. Back in October 2020, the microfinance industry did a collective assessment of the liquidity crisis and reached a conclusion that one-fifth of the portfolio restructured under the SBP scheme is likely to default.

Consequently, the sector’s outlook changed significantly. Overall economic downturn and more specifically asset quality issues of COVID impacted portfolio impacted the sector’s growth. While the central bank stepped up to provide relief to customers, the rescheduling and loan deferment resulted into masking potential losses which were realized later when SBP’s relief period expired.

“The core reason behind customer default was the massive decline in the purchasing power of the borrowers. Therefore, the NPLs ratio of the MFBs exceeded 25% of the rescheduled portfolio. Currently, the overall risk profile of the sector is marked by higher cost of doing business in line with increased discount rate, asset quality issues resulting in portfolio losses and liquidity challenges and changed client behavior on account of subsidies offered to clients during pandemic. Consequently, profitability of the entire microfinance sector was adversely affected resulting in capital erosion. All put together, this has contributed to significant operating losses for many players in the sector and to the extent of breaching the regulatory requirement of capital adequacy prescribed by the central bank. The stress on capital adequacy ratio (CAR) was evidenced across the sector as 4 microfinance banks out of 7 major players are facing regulatory breach and in the process of raising capital,” reads VIS rating report.

Fast forward to 2023 – deteriorating CAR

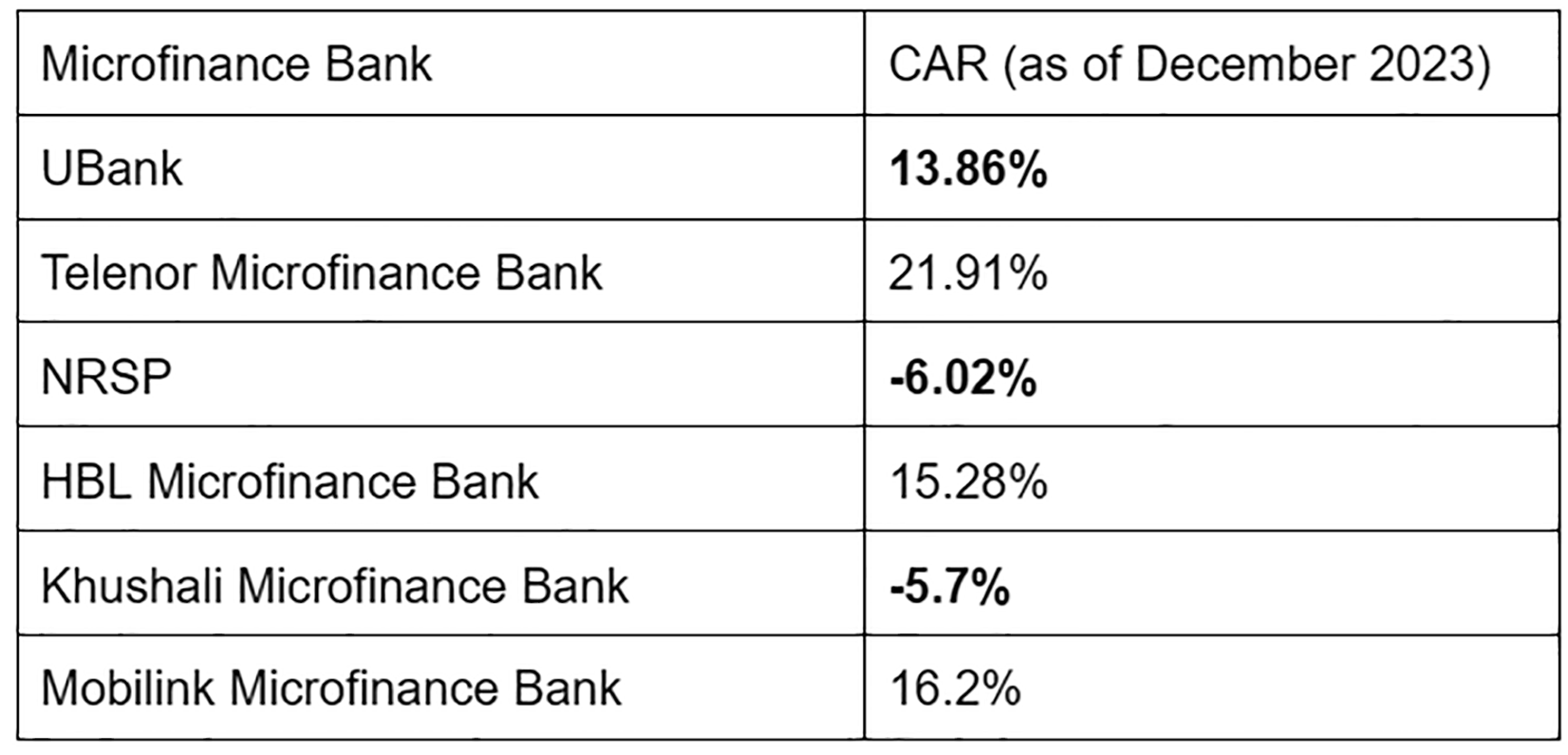

The microfinance sector in Pakistan is still in recovery mode. Some banks are still reporting losses to the point that they have breached the regulatory requirement for capital adequacy ratio (CAR). CAR is the regulatory liquidity requirement which banks have to maintain. Currently, a minimum CAR of 15% is to be maintained by the MFBs. The calculation of CAR is based on the capital held by banks divided by the aggregate of the bank’s risk weighted assets. As a rule of thumb, to improve CAR you have to decrease risk and increase capital.

The table below shows the CAR for some of the prominent players in the market. As the numbers show, the CAR for most players has declined to dangerously low levels, even going into negative.

“Regarding vulnerabilities in the microfinance sector, the authorities have asked owners to provide time-bound recapitalisation plans where necessary. This approach has been successful in returning two institutions to regulatory minimum standards. Staff welcomed work on a plan to strengthen internal control systems in the SBP’s lending operations but urged that the counterparty eligibility policy include a requirement that counterparties are financially sound,” reads the recent IMF report.

Telco based MFBs

In 2023, PTCL group, parent company of UBank injected Rs1.6 billion to to address potential statutory shortfalls. However, recent reports with corrective measures mandated by the SBP shows that the bank reported a loss of Rs 2.3 billion before taxation in 2022. With tax reversals, the loss amounted to Rs 876 million. The bank’s losses continued in 2023 as UBank recorded a loss before taxation of Rs 1.1 billion, and a profit after tax of Rs 750 million following tax reversals. The bank’s accumulated losses amount to around Rs 1.9 billion which shows that UBank is in the same league as other undercapitalised microfinance banks.

Hence, as of March 2024, equity has further declined to Rs 3.5 billion. Resultantly, the Bank’s capital adequacy ratio fell below the regulatory threshold of 15% to 13.86% at the end of 2023. Interestingly, as per the subsequent financial statement released for Q1 2024, the ratio fell further to 9.4%.

Read: From profitable highs to equity injection calls, what went down with U Microfinance Bank in 2023?

This isn’t the first time this has transpired in the microfinance industry and there are remedies in place. And Ubank is exactly moving towards that. The Board of Directors of PTCL convened on April 18, 2024, and agreed to support the bank’s capital structure through the following measures:

- Conversion of PTCL preference shares into ordinary share capital of Rs. 1,000 million.

- Conversion of PTCL subordinated debt of Rs. 1,200 million into ordinary share capital.

- Additional cash equity injection of Rs. 1,200 million.

These capital enhancements would have increased the bank’s total capital adequacy ratio to 15.4% as of March 31, 2024, and to 16.6% as of December 31, 2023.

But all is not gloom as the other two telco led microfinance banks not only meet the CAR requirement, but are also profitable. Interestingly, both of them are focussed on digital lending (nano lending).

Telenor Bank has one of the strongest industry CAR of 21.9% at end of December 2023 which improved to 22.75% at the end of first quarter of 2024. The bank’s CAR at the end of 2019 stood at 19%. This improvement is due to successive capital injection from the sponsors.

The sponsors injected the bank with liquidity, cleaned up the books, shut down branches, and migrated to new business model. However, other microfinance banks are stuck because their sponsors are either unwilling to or are unable to clear the books to move forward.

Telenor Bank also managed to become profitable for the first time in five years in 2023 after 2017 with a net profit of Rs 502 million. In the same year, the bank got an

This shift towards profitability came about in the same year when the bank received no objection for digital retail bank license. As per Data Darbar, Telenor Bank’s focus on nano led to growth in income and hence profitability.

Similarly, Mobilink Microfinance Bank’s gross loan portfolio encompassed nano loans totaling Rs. 7.7 billion. The bank’s CAR was above regulatory requirement and net profit of Rs 1,033 million.

Commercial bank players

HBL Microfinance Bank’s CAR has remained just above the statutory requirement at 15.02%, however, the bank recorded a net loss in first quarter of 2024 of Rs 721 million. Soon after in April 2024, Habib Bank Limted, parent company of HBL MFB announced capital injection of Rs 6 billion into the MFB, which implies that without the injection the ratio might have fallen below the threshold.

On the other hand, Khushali MFB incurred a negative CAR of -5.7% as at December 2023 as per VIS report. The bank has not released its yearly report showing that it is grappling with losses and negative equity.

Bleak future for microfinance sector?

Overall, the sector has been struggling. Part of the problem is negligence on part of the regulator. “The regulator has not paid much attention to microfinance sector in last 10 years. Regulator was neither progressive nor responsive at the time of crisis. Response was very slow. MFBs repeatedly went to SBP to advocate but the SBP’s stance was that it was ‘observing’,” lamented an industry professional.

To effectively scale productive financing for small agriculturists and farmers, regulatory intervention is crucial. This involves providing loan loss guarantees for risky loans to incentivise microfinance banks to extend credit to these sectors. The shareholders/sponsors of microfinance bank are commercial entities, not not-for-profit organisations. Since these shareholders are driven by commercial interests, they are unlikely to invest their capital in extremely risky loans that support the development sector without a viable business case.

Therefore, the regulators need to step in and participate in risk through guarantees and schemes or offer schemes that incentivises risk taking. “Although there is significant potential for development in this sector, the regulator has shifted its attention to larger economic issues, neglecting the microfinance sector”, lambasted the industry source. As a result, access to finance and credit for MSMEs has not improved.

Besides, The microfinance sector has seen limited innovation, with most banks focusing on gold-backed bullet lending. This lack of diversity in financial products hinders the growth of microfinance. Conversely, there has been substantial progress in digital banking, with initiatives like RAAST, changes in digital onboarding, and the introduction of DRB licenses. These efforts have driven significant advancements in digital banking. However, interest in microfinance licenses could decline unless the regulator revisits the licensing structure of microfinance banks (MFBs).

In fact, fintech players have been expressing their interest in the microfinance bank licence and have been exploring how they can leverage this license for their digital business. For example, ABHI, a fintech operator, and TPL Corporation, a leading conglomerate, have expressed interest in the acquisition of FINCA Microfinance Bank. The regulator allowed the entities to do due diligence on the microfinance bank for the next stage. Similarly, Advans Microfinance Bank is being acquired by MNT Helan, the Egyptian digital payment provider while Advans will be exiting Pakistan’s market.

Therefore, the regulator needs to enhance the commercial business case for microfinance banks to reignite shareholder interest and make these ventures viable again.