It is the advertisement that caused a stir in Pakistan’s marketing world. Olpers, a brand of milk owned by Engro Foods recently launched a television commercial that showed a package of an unnamed rival, though the packaging is distinctly similar to that of the yellow packets of Nestlé’s Nido Fortigrow. A young boy asks his mother if the package is ‘not milk?’ (kya ye doodh nahi hai?), to which his mother exasperatedly says it isn’t, and that ‘ye tou teil milli safaidi hai’ (its a mixture of oil and white powder!). Following this, the grandmother in the commercial then questions in disgust, ‘Yaani ke itne saal se hum dhoka kha rahay thay?’ (So we were being deceived all these years?).

Needless to say, even though Nestlé was not named in the ad, the company did not appreciate the implication that they had been less than forthcoming about the nature of the product. Nestlé’s ad agency, Ogilvy & Mather confirmed that Nestlé Pakistan had taken legal action in the form of a stay order for airing the television commercial against Engro Foods. The Olpers ad is currently still airing on most television channels, but without the part where the boy mentions anything about the yellow packaging.

“It remains to be seen whether this TVC has done damage to the business in terms of reducing sales or market share, since it has only been a couple of weeks since the advertisement was aired,” the agency added.

On the surface, this is the story of two giant companies competing against each other, with the smaller competitor – Engro Foods – seeking to gain market share by highlighting what its brand managers perceive as the contrast between their product and that of their bigger rival, Nestlé Pakistan. Yet scratch beneath the surface, and this is really a story of two large companies struggling to gain market share against a much bigger, much more persistent rival: loose, unpackaged, unpasteurised milk, sold at dairy shops throughout the country.

This ad, and the legal action it has prompted, is a minor skirmish in a much broader battle for supremacy of Pakistan’s milk market, and it is one in which Engro Foods and Nestlé Pakistan are more allies than rivals. Both companies compete against each other for share of the packaged milk market but have a common interest in working to expand the market for packaged milk relative to unpackaged milk.

The story of packaged milk

The history of packaged milk in Pakistan starts with its packaging. In 1956, the Wazir Ali Group set up a packaging company – Packages Ltd – in collaboration with Tetra Pak, the Swedish packaging giant. Packages quickly became the leading supplier of packaging material to Pakistan’s nascent packaged food industry.

In 1976, during a routine review of the company’s operations, the management found that one of their machines that made packaging for beverages was underutilised. Rather than simply let the machine remain underutilised, or even eliminating the business line entirely, Packages decided to invest in vertical integration by creating its own downstream user of beverage packaging.

Thus was born Milkpak, a brand that remains one of the leading packaged milk brands in the country and one of the most recognised overall.

Milkpak Ltd was incorporated in 1979 and began production of its eponymous brand of packaged milk in 1981. By 1984, the company expanded into the fruit juice market, acquiring the “Frost” branded line of juices from its parent company Packages Ltd. The next year, Milkpak launched its brand of butter, and the year after that, a line of packaged cream.

In 1988, Nestlé, the multinational food giant based in Switzerland, bought a controlling stake in Milkpak Ltd, and the company came to be known as Nestlé Milkpak Ltd. The Nestlé acquisition brought significantly more resources – both in terms of capital and technical expertise – to the packaged food industry in Pakistan, which sought to grow the share of packaged food relative to unpackaged food in Pakistan.

For much of the 1990s and early 2000s, for instance, Packages Ltd, in collaboration with Nestlé Milkpak, ran long informational advertisements on television (back then, there were only two state-owned channels), seeking to educate the Pakistani middle class consumer on the safety features of packaged milk and the health benefits of avoiding unpackaged foods. The strategy was clear: packaged food companies will all grow together if more people realise that the product offering was better than that of unpackaged food.

The effort was less about creating an individual brand personality – though there was certainly some of that as well – and much more about creating the perception of additional safety around the entire category of packaged foods.

Yet despite all of these developments, packaged milk remained a relatively small segment of the overall market for milk in Pakistan, which itself is one of the largest categories of consumer spending by Pakistani households.

According to household spending data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, the average Pakistani household spends 9.5% of its monthly consumption expenditures on milk and dairy products, the overwhelming bulk of which is spent on milk alone. According to Profit’s analysis of that data, that amounts to approximately Rs3,373 per month per household on milk in 2018.

That makes milk the single most valuable prize in the competition for share of the Pakistani consumer’s wallet. Small wonder then that just when Nestlé began to gain significant traction in the Pakistani milk market, a well-financed competitor entered the market.

In 2006, the Engro Corporation launched its first consumer-facing subsidiary, Engro Foods, and their very first product was a line of packaged milk – under the brand name Olpers – that would be a direct competitor to Nestlé’s Milkpak.

But for the first six years of Engro Foods’ existence, far from being seen as a threat to Nestlé’s supremacy, Olpers helped expand the market for packaged milk. In 2005, the year before Engro entered the market, packaged milk accounted for just 3.0% of the total market for milk in Pakistan, by rupee value. By 2012, that share had jumped to 7.8% of the total market.

In other words, Engro and Nestlé were not taking market share from each other, they were both taking share from the unpackaged milk market.

And in public-facing statements, Nestlé’s management acknowledged that market share within the packaged segment did not matter to them. “Take the example of yoghurt. We are 80% of the market when it comes to packaged yoghurt. But that packaged segment is only 2% of the total market,” said Ian Donald, then the managing director of Nestlé Pakistan, in a 2012 interview with The Express Tribune. “So it doesn’t really matter what our market share is. We need to grow the whole packaged segment.”

Nestlé Pakistan and Engro Foods were never exactly friendly with each other, but in the period between 2006 and 2012, they did not think of each other as their primary competition. But then matters stalled. And that is when the two companies started getting into a stiffer competition with each other.

The post-2012 stagnation

Since 2012, the market for packaged milk has seen much slower growth, and the numbers show it.

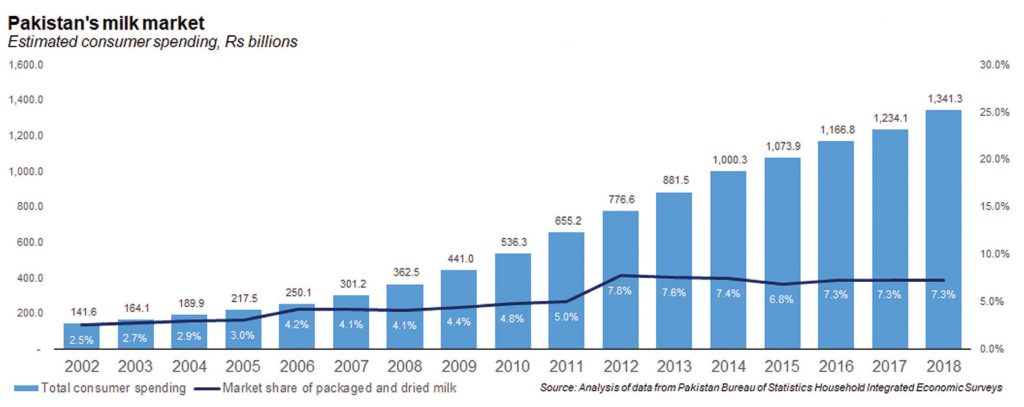

First, it is important to acknowledge that packaged milk has continued to make strides in Pakistan’s dairy market. According to Profit’s analysis of data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, between 2002 and 2018, the market for milk and dairy products in Pakistan grew by 15.1% per year (inflation during that time averaged 8.4% per year). Spending on packaged milk has grown by 25.7% during that same period. As a result, the share of consumer spending on packaged milk relative to total spending on dairy products has risen from 2.5% to 7.3% between 2002 and 2018.

However, there is a considerable difference between the years between 2006 and 2012 and the years between 2012 and 2018.

Between 2006 and 2012, total consumer spending on milk and dairy products grew by 20.8% per year. Spending on packaged milk during that time grew by an astonishing 36.3% per year (inflation during this period averaged 11.8% per year).

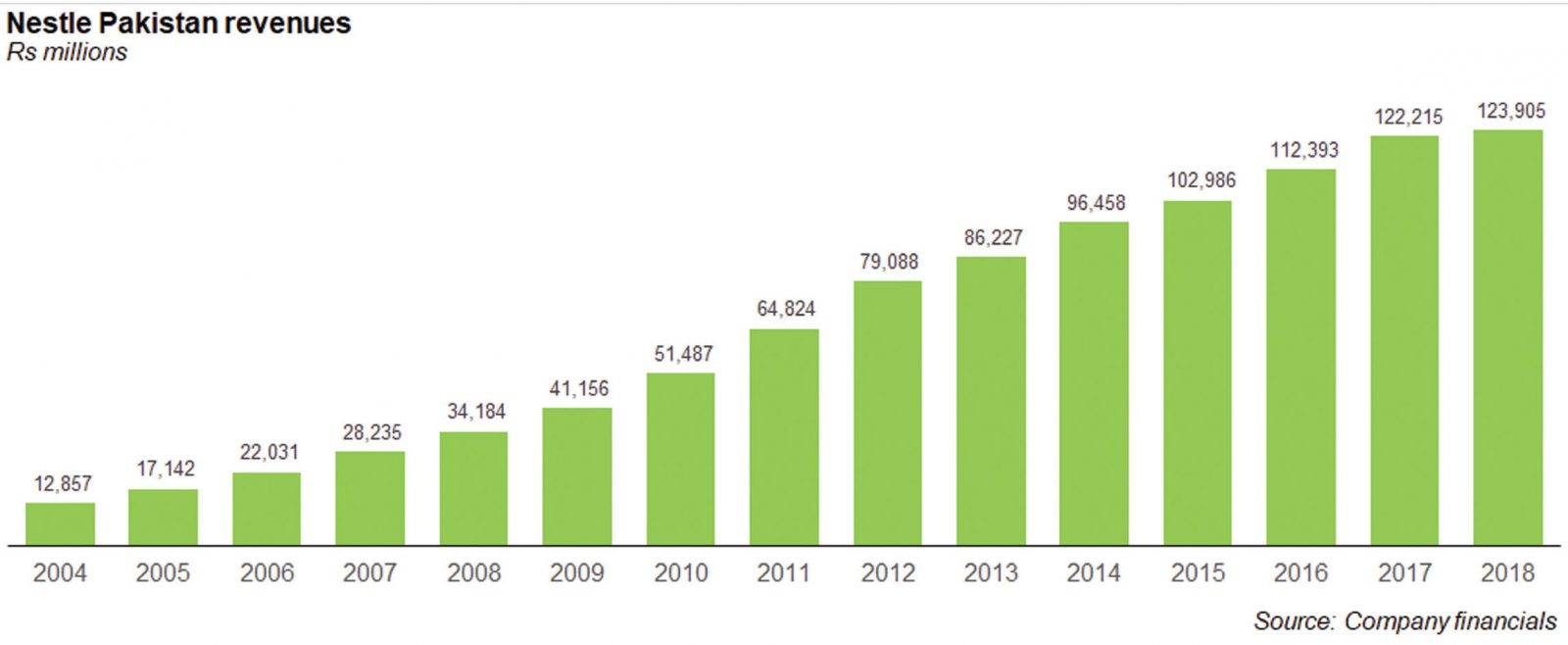

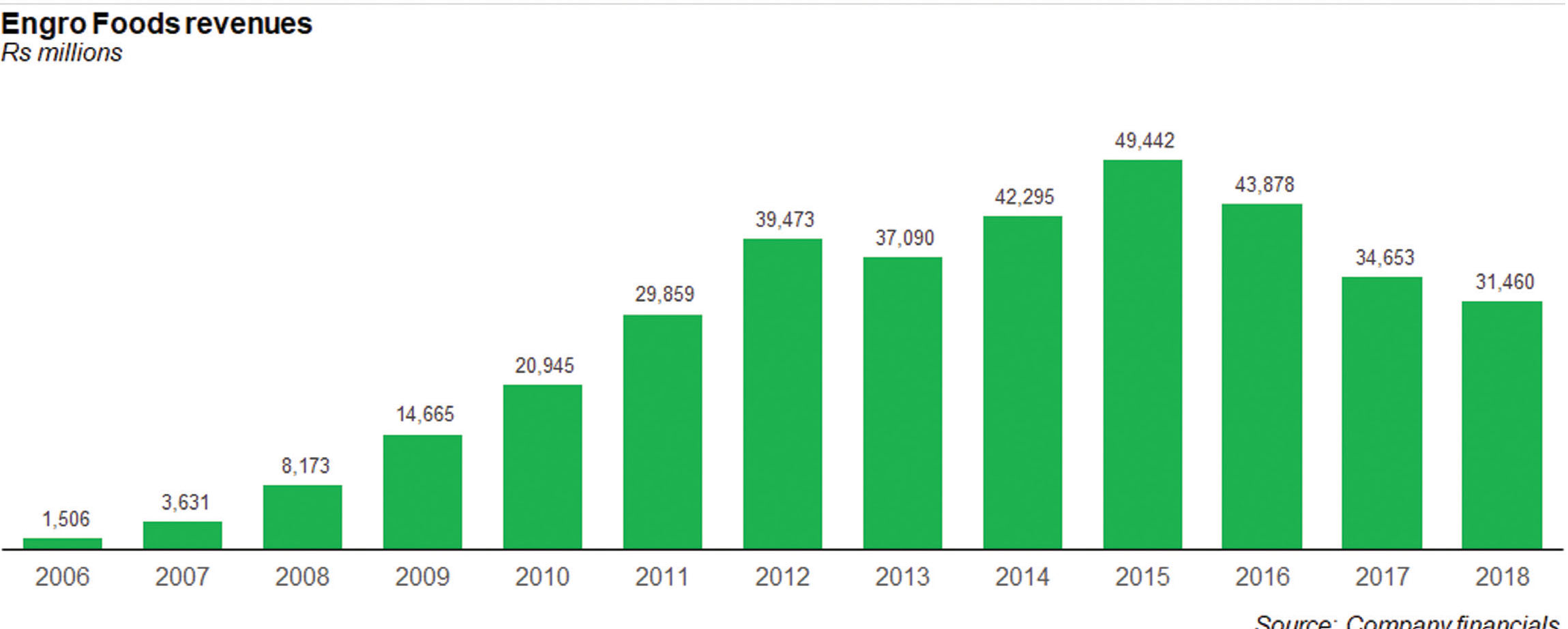

As a result of this tremendous industry growth, both Nestlé Pakistan and Engro Foods did very well. During this period, Nestlé Pakistan grew its revenue by a compound annualized growth rate (CAGR) of 23.7% per year, taking is annual revenue from Rs22.0 billion in the calendar year 2006 to Rs79.1 billion in 2012. Engro Foods did even better during that time, growing its revenue at a CAGR of 72.4%, from Rs1.5 billion to Rs39.5 billion.

The overall packaged food industry continued to take share from the unpackaged industry, rising from 4.2% of consumer spending on milk in 2006 to 7.8% in 2012.

At that point, however, matters began to stall. The dairy market as a whole grew more slowly during that period, at about 9.5% per year (inflation during that time averaged 5.2% per year). However, what is interesting is that unpackaged milk appears to have made somewhat of a comeback, growing at a slightly faster average of 9.6% per year, while packaged milk grew at an average of just 8.8% per year during that same period. As a result, between 2012 and 2018, the packaged industry’s share of the milk market went down from that 7.8% to 7.3%.

It is not entirely clear exactly why the packaged industry started retreating in terms of market share after so many years of gains, especially since the economy did not materially deteriorate during the years between 2012 and 2018, at least in the early part of that period.

What is abundantly clear, however, is that the impact of that retreat was not uniform on the two big players in the industry. Nestlé Pakistan saw a dramatic slowdown in its revenue growth, which went from a CAGR of 23.7% in the six years before 2012 to 8.1% in the six years since 2012 (through the end of the third quarter of 2018, the latest period for which data is available).

Engro Foods, however, saw a sharp drop in overall revenue growth, going from a CAGR 72.4% in the six years prior to 2012 to -3.9% in the years since then. The decline has been even more dramatic since 2015, the last full year during which Engro Corporation was the majority shareholder of Engro Foods. Revenue has declined 36.4% since then.

This differential fate is at least in part due to the fact that Nestlé Pakistan has a larger stable of brands and products that it sells compared to Engro Foods, and thus has a more diversified revenue stream that is not quite as strictly dependent on the milk and dairy sector as its smaller rival. What that means is that Engro Foods feels the urgency of creating and marketing new products as a means of not just catching up with its larger competitor, but also of diversifying its business and mitigating the risk of its significant revenue decline repeating itself in the future.

The ad wars begin

Between 2006 and 2012, Nestlé had watched Engro Foods growing its revenue and market share in many of the markets in which it competed, and for most of that period, it did not feel threatened. Yes, the relative numbers were moving in Engro’s favour, but the absolute numbers for both companies were growing. In 2013, however, came the first absolute revenue decline for both companies, followed by a year of relatively slower growth in 2014, and suddenly, it appeared that Nestlé Pakistan would have to rethink its corporate strategy if it was going to retain the title of the largest food company in Pakistan.

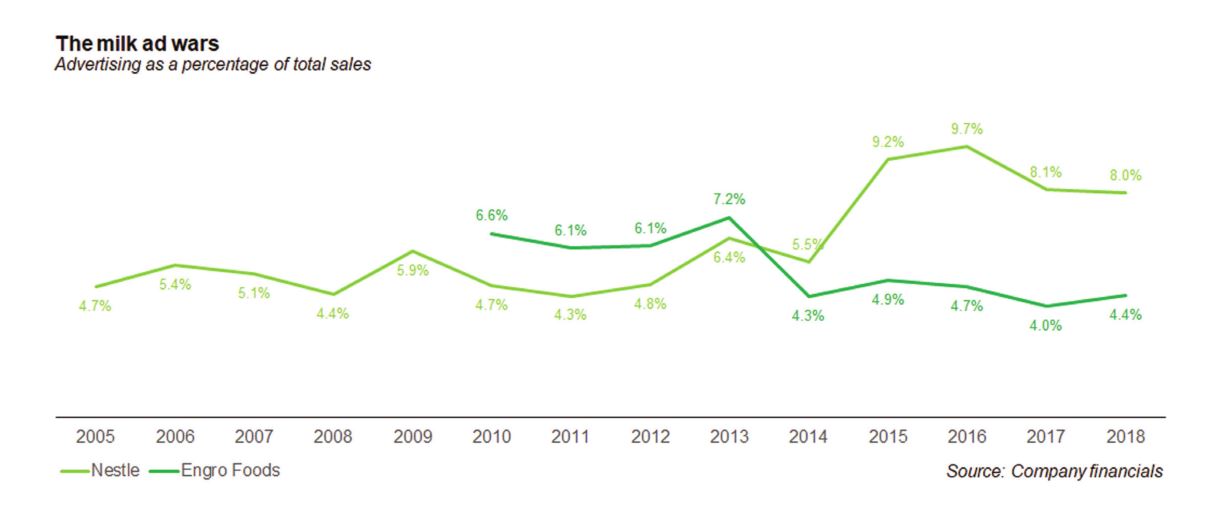

The strategy Nestlé chose was a dramatic uptick in its advertising spending, a near doubling that saw the company’s total advertising expenses jump from Rs5.3 billion in 2014 to Rs9.5 billion in 2015. The company invested heavily in promoting its brands and building up a greater brand equity in the minds of the Pakistani public. (For those of you wondering, this increase does not appear directly related to Nescafe Basement, the music show sponsored by Nestlé Pakistan. That show started in 2012, and its costs show up in the form of a marketing expenses increase in that year’s financial statements.)

Engro Foods, being a smaller company, did not have the capacity to keep pace with that massive increase in advertising spending by Nestlé Pakistan. Nonetheless, the company did catch its rival’s advertising spending rise and responded by raising its own spending by about a third to Rs2.4 billion in 2015.

Since that year, however, the decline in revenues has meant that Engro Foods has had fewer resources available to invest in its marketing and brand building initiatives.

The “safaidi” controversy

At the heart of the controversy between Engro Foods and Nestlé Pakistan is the differences between the two products. “Olper’s Full Cream Milk Powder is produced by removing the moisture content (water) from natural, full-cream milk and by adding some extra nutrients like vitamins and calcium. Once water is added back, it becomes Full-Cream Milk, enriched with calcium & vitamins,” said Engro Foods’ corporate relations department, in a statement issued to Profit.

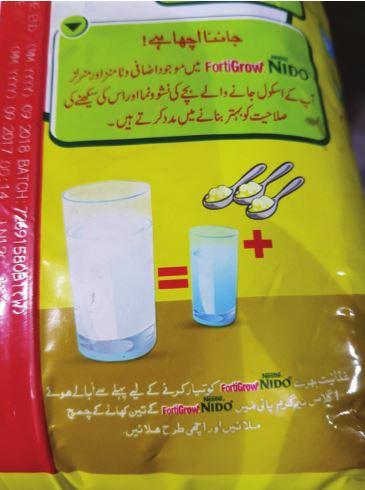

Nido Fortigrow, which has a market share of more than 90% in the powdered milk category, includes milk solid non-fat (MSNF), milk fat, vegetable fat, emulsifier, vitamins, minerals, and soya lecithin in its ingredients. On its package, it says on the front of the package that it is ‘milk powder with milk and vegetable fat’.

Both brands have similar ingredients, are powder-based, ultra-heat treated, and contain additives which add to the milk component, implying that both are milk products enhanced with other ingredients.

Nestlé Pakistan believes the Engro Foods advertisement is “factually inaccurate”, according to a company spokesperson.

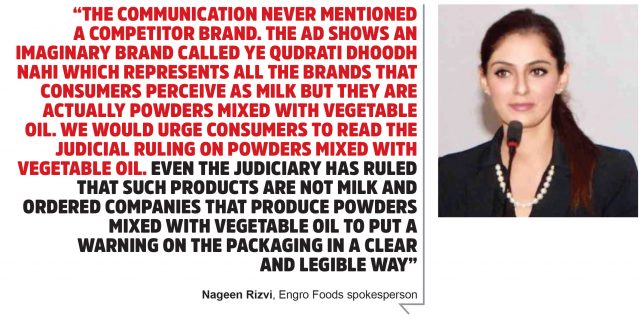

For its part, Engro Foods categorically states that it did not target Nido or any other actual competitor brand in its target. In a statement issued to Profit, Engro Foods spokesperson Nagin Rizvi said: “The communication never mentioned a competitor brand. The ad shows an imaginary brand called “Ye Qudrati Dhoodh Nahi” which represents all the brands that consumers perceive as milk but they are actually powders mixed with vegetable oil. We would urge consumers to read the judicial ruling on powders mixed with vegetable oil. Even the judiciary has ruled that such products are not milk and ordered companies that produce powders mixed with vegetable oil to put a warning on the packaging in a clear and legible way.”

Olpers is promoting itself as ‘full cream milk’, while Nido promotes itself as ‘milk powder with vegetable fat’. Nido, like Olpers is also made from natural milk, claims Abdul Sabhoor, Nido’s Business Head at Ogilvy & Mather. However after its fortification with a high standard fatty acid/vegetable fat, it cannot be claimed as ‘real milk,’ he adds.

This is not the first time competitive advertisement has been used in Pakistan. Coca Cola launched its ‘Zaalima Coca Cola pila de, chai ko thand kara de’ (“Give me a Coca Cola, cool it with the tea”) campaign featuring Maya Ali and Ahad Raza Mir last year. The punch line, ‘chai ko thand kara de’, targeted the country’s leading tea brands, Unilever Pakistan’s Lipton and the independently owned Tapal.

Lipton responded with its own digital campaign, posting a cup of tea on digital and social media platforms that said, “Pakistanis love chai zaalima…nice try’, with a caption that said, ‘Pakistanis have no doubt when it comes to chai’. Lipton also started using the hashtag ‘#Pakistan’sBestBeverage’ to counter the onslaught by Coca Cola. Lipton came up with its ‘Tum, mein aur aik cup zaalima chai’ campaign with a hashtag that said, ‘TapalDanedarZalimChaiBanaye’.

Following this, even Nestle joined in the party by showing a chilled glass of Coke with a person dipping in a biscuit – the ad read, ‘Dunk now Zaalima’ and a caption that said, ‘It’s not even a question of choice, #ZaalimaChaiPilaDe’.

Zeban Syed, Business Director at Ogilvy & Mather says, “Brands often use various tactics to viciously compete with each other. Whether this practice is right or wrong is another debate since there are no hard and fast laws governing these practices and so, for television channels and agencies, it’s mostly about the business that their clients are bringing in. Clients, on the other hand, should take more responsibility when they make certain advertisements and use their competition”.

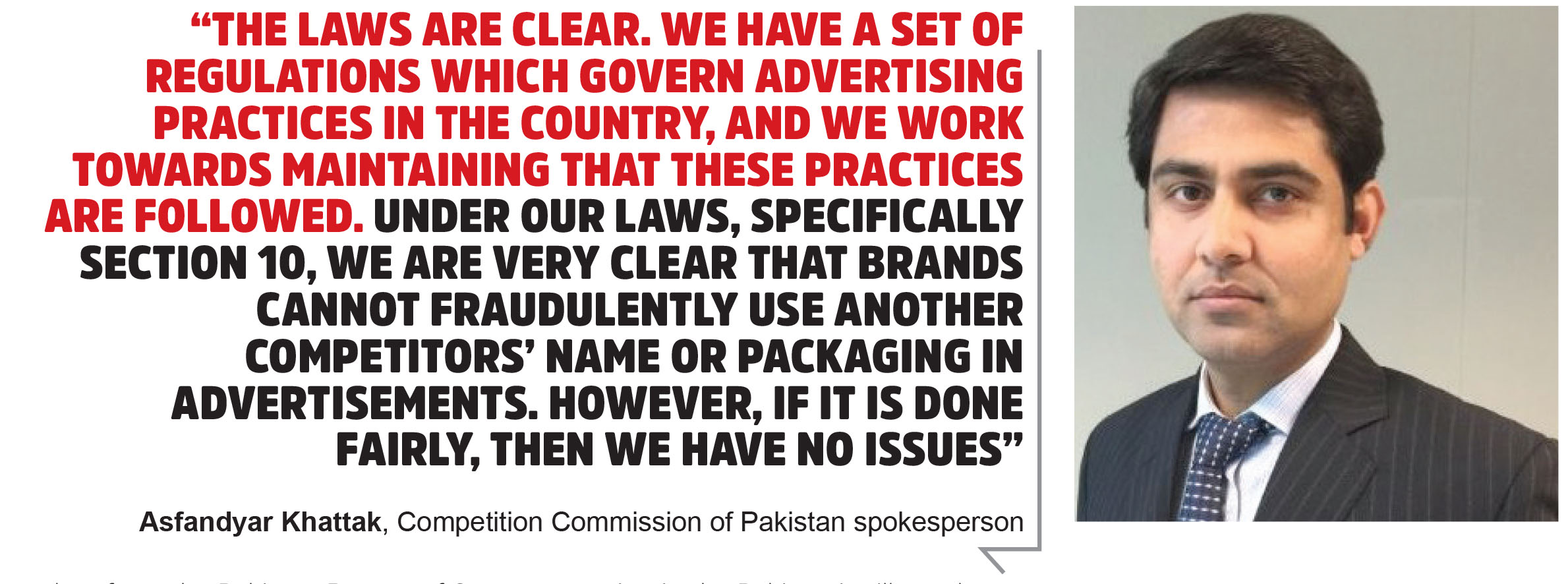

There are, however, at least some laws that govern corporate behaviour when it comes to advertising practices. The Competition Commission of Pakistan (CCP), under Section 10 of the 2010 Competition Act, defines “deceptive marketing practices” as “the distribution of false or misleading information that is capable of harming the business interests of another undertaking, false or misleading comparison of goods in the process of advertising; or fraudulent use of another’s trademark, firm name, or product labeling or packaging.”

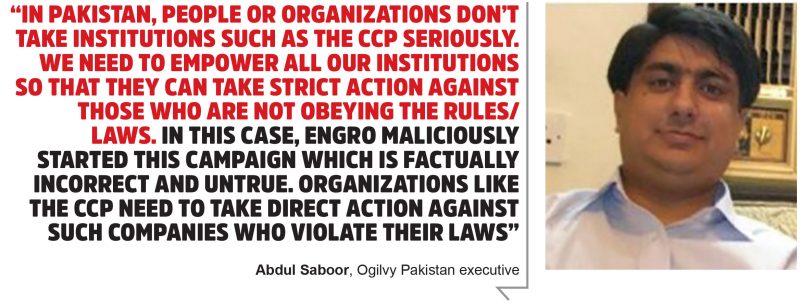

Abdul Saboor, Head of Nido at Ogilvy & Mather says, “In Pakistan, people or organizations don’t take institutions such as the CCP seriously. We need to empower all our institutions so that they can take strict action against those who are not obeying the rules/ laws. In this case, Engro maliciously started this campaign which is factually incorrect and untrue. Organizations like the CCP need to take direct action against such companies who violate their laws.”

Asfandyar Khattak, the director of media and advocacy at the Competition Commission says, “The laws are clear. We have a set of regulations which govern advertising practices in the country, and we work towards maintaining that these practices are followed. Under our laws, specifically Section 10, we are very clear that brands cannot fraudulently use another competitors’ name or packaging in advertisements. However, if it is done fairly, then we have no issues.”

Engro Foods states that it believes its advertising content was not a violation of the law. “We are fully compliant with CCP rules,” said the Engro Foods spokesperson. “Having a full cream milk powder brand vis a vis a powder which is mixed with vegetable oil is a genuine advantage.”

Gaining share, ignoring the gorilla in the room

In the powdered milk category. Engro’s market share is estimated to be smaller than that of Nido according to analysts who track both companies. The powdered milk category was originally meant to be just a tea whitener, with Tarang by Engro Foods and Everyday by Nestle.

However, in their efforts to go after the unpackaged milk category, both companies have been seeking to create a product that has a lower price point, which often means adding ingredients that are cheaper, and thus change the product from being actual milk to being some sort of beverage that can at best be described as dairy-derived, but not actually milk.

Indeed, orders from the Punjab Food Authority prohibit companies from calling such beverages “milk”. Engro Foods brands its product “Omung” a beverage that is an alternative to unpackaged milk, but does not call it milk itself.

However, in seeking to create these “milk-adjacent” products that are meant to capture market share from the unpackaged milk sold at dairy shops throughout the country, the packaged milk companies – both Engro Foods and Nestle Pakistan, as well as their smaller competitors – are forgoing the brand advantage that they have spent decades building: that theirs is a purer, healthier, more hygienic milk.

If they can no longer even legally call it milk, how are they now any different from the neighbourhood gawala (dairy shop owner) who they spent the better part of the 1990s accusing of “adulteration” of milk, going so far as to say: “the reality is that the gawala does not add water to his milk, he adds a little milk to water.”

Some consumers, particularly those in upper income neighbourhoods that were the early adopters of packaged milk, have already started abandoning these brands in favour of locally sourced milk from dairy shops and delivery services that are pricier than even the packaged milk brands, but provide their consumers with greater confidence in the quality and purity of the milk they produce.

In their effort to compete with the gawala, the packaged milk companies have become exactly what they criticised about the gawala and in turn are already beginning to lose their first customers.

Rather than focusing on competing with each other for basis points of market share, these companies might be better served sticking to the strategy that initially built their businesses: gain the consumer’s confidence that they offer a higher quality product that is worth paying a little extra for.

Very Well Written Article by By Shoaib Pervaiz and Farooq Tirmizi.

Detail you guys have put in the Article are absolutely true.

Good Work Guys…………… Keep it up.

Regards,

Public Awearness Message about Haleeb fake Milk and Juices:

Haleeb Nutra Hygin has pig fat traces and company import this pig fat in dry form from USA and key objective is to make milk thick. Haleeb has a plant in Bahi Pheru and their expert and ex Head of Quality explained this all.

Also company adds formaline in their milk. Its a chemical that makes Haleeb Milk last longest and its 100 days expiry.

Flava is the company new flavoured milk and its all the same. Fake milk , made out of vegetiable fat.

To make public foolish, company launched Chaunsa Chaunsa which is a poorest class juice.

Please beawear and educate other public

Due to supply interruption in gourmet, I tried Nestle Milk Pak. Since then everything has become tasteless for me. Really bad experience.

Gourmet issues are in common knowledge now. UHT milk pass through a process to remove odors & gives a flat taste thats a right observation. Pasteurized milk like anhaar/prema/Cakes & Bakes / Adams are available.

Such a lengthy thesis on Milk in Pakistan, the fact remain that packaged milk available in pakistan is not affordable by 90 % consumers of 200 million population of pakistan nor technically it is ideal as developed countries have left this technology and by and far use pasturized milk. as the proveb goes CANALS OF MILK FLOWING IN A NON AGRI COUNTRY LIKE UK, where as in Pakistan, a predominantly agri country, the biggest challenge is to make available pure milk for the majority of population on affordable prices. In Pakistan, billions of rupees are spent on ads making the product further dearer, where as hardly any penny spent on ads of milk and milk products in UK or say European countries.This phenomena obviously make poor pakistanis victom of mutinationals. That is pathetic.

Nestle knows its product is sub-standard. They have been fooling the pakistani masses: duping them into believing white chemical they drink is milk.

I dont care about Olpers, but at least their ad was exposing nestles chemical poison, that we feed our kids.

And the ad itself does not mention or categorically show Nido. However if Nido assumes that the shit product showcased in the ad was theirs, it kind of proves the point in the ad.

Youtube search: Nido ad

You will see almost all results from Pakistan, because this shit does not sell in developed countries. Pakistanis are foolish, they think any thing foreign must be better or healthier, but its a multinational scam.

A good analysis but the fact is that these Milk companies in Pakistan need to be honest about their offerings and get certified for halal and quality of their products. Many milk products in western countries are now getting Halal certified.

any one conform exact olpers milk market share

excellent article. I pay more for the milk by going to the milkman very early in the morning and watching him milk his buffaloes and giving me the pure milk directly. I spend around 9000 rupees per month on this milk plus petrol plus waiting in the morning. my children’s health is extremely important for me. I don’t want to buy olper or milk pack as it’s just not milk. simple as that.