Call any major bank in Pakistan today and ask them about their debit cards. Habib Bank Limited (HBL), United Bank Limited (UBL), Allied Bank Limited (ABL), MCB Bank – all of them will give you an eerily similar rundown of the cards they offer and the services those cards provide. And under the tight smiles and polite suggestions that are the armour of salespersons and phone bankers, the message they are sending is loud and clear: Do. Not. Get. PayPak.

Here’s an excerpt from the transcript of this reporter’s phone conversation with a representative from one of the top Pakistani banks:

Reporter: Which debit cards does the bank offer?

Bank representative: We have a ‘classic’ card.

What is the card branded as?

It’s a Visa.

So it’s a Visa classic. Do you offer PayPak?

Yes, but you can not use that internationally and the daily withdrawal limit is only Rs25,000 whereas for ‘classic’ it is Rs100,000. Oh and the daily transfer limit from ATMs is also less with PayPak.

And how much do you charge for PayPak?

Sir, it is Rsxxxx plus FED. But you can not use that internationally and the withdrawal limit is only Rs25,000. Whereas ‘classic’ is Rs100,000. Also, the transfer limit on the classic is higher than PayPak.

The amount you quoted is for issuance or annual?

Issuance and annual

And how much does Visa cost?

Sir, it is Rsxxxx plus FED and you can use that internationally and the withdrawal limit on ATMs is also higher.

Reporter: Okay, thank you for your time.

Every other one of the seven banks we called had a similar script, ready to give a similar sales pitch. This makes one thing abundantly clear. The suspicion that most Pakistani banks are trying their best to freeze out customers from getting PayPak debit cards. The question is why would they do that and why is that a problem? After all, on January 31, 2020, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) issued a circular to bank presidents carrying sweeping directives for the banks to overhaul the payment infrastructure of the country and make PayPak the priority card.

Among other directives, the SBP ordered banks to offer the State Bank-approved Domestic Payment Scheme (DPS) card PayPak as the default card at the time of issuance or renewal of debit cards. Accordingly, an adjunct set of guidelines directed banks that the card requesting customers shall be offered the following options: either an exclusive DPS card or a DPS card co-badged with an International Payment Scheme (IPS) was to be offered as the priority, whereas exclusive IPS cards were to be furnished to bank customers upon written request of these customers.

Essentially, this means that when you walk into a bank and open an account, under SBP directives, the bank is supposed to offer you a PayPak debit card, and if you want a card that can perform international transactions as well, then they are supposed to offer one that has both the PayPak and Visa or Master logo on it. It is only if you go and specifically request a non-PayPak card that the bank can provide one, and even then, they have to give you a form to fill out and submit.

The SBP circular was supposed to be a turning point in the history of Pakistan’s payments industry. The hope was to establish a young kid from the block, the locally born PayPak as the dominant player in the financial payments ecosystem. The banks are visibly and blatantly resisting, but once again, the ‘why’ of it all becomes increasingly confusing because these very banks are patrons of PayPak.

You see, PayPak is owned by 1Link, which is owned by a consortium of 11 banks that was originally formed to allow inter-bank ATM usage and transactions.

So why was PayPak formed in the first place by 1Link if it was only going to be spurned by the banks behind it? Did something go wrong, or is the SBP using PayPak in a way the banks never anticipated? And even more importantly, what was the logic behind the circular that the SBP sent and their desire to see PayPak established? Profit investigates.

On the origin of payment cards

“Do you even know what you are paying for? What the value proposition of a Visa or a Mastercard branded debit card is for a Pakistani consumer?” one of our sources asked us during a conversation about the birth and evolution of PayPak.

Normally, when a source turns the question on its head and begins quizzing the reporter, it can result in the wounding of professional pride. In this case, it was a poignant reminder that in Pakistan, there is very little understanding of what exactly Visa and Mastercard do. But when you think about it, if you have a Visa card for example, in Pakistan the one thing you will most likely use it for is withdrawing cash from an ATM in exchange for a fee.

“ATM withdrawals are not what a Visa or a Mastercard is good for,” the source guffawed. “But the majority of the transactions on debit cards are ATM withdrawals. You’re all fools to pay thousands of rupees in fees for a card that does something that a 100 ATM-only card can also do.”

Let’s pause here and delve a little into the history of how Visa and Mastercard first entered the Pakistani market and what they have been doing since. In 1999, Askari Bank and ABN Amro Bank decided to collaborate with each other to create the first ATM switch to enable both banks’ customers to make ATM transactions at each other’s ATMs.

The switch was labeled as ‘AA Switch’ after the initials of each bank’s name. In 2002, HBL joined the ATM network and the switch was rebranded as 1Link. Initially, 1Link was not labeled as a separate entity and was registered as a Guarantee Limited company.

A competing ATM switch was launched by MCB Bank in 2001 by the name of MNET that enabled interoperability between different banks like First Women Bank, Samba Bank, and CitiBank.

The then Governor of the State Bank, Ishrat Hussain, saw this as an opportunity to extend ATM interoperability to the entire banking industry and directed all the banks to join either 1Link or MNET. A total of 11 banks had joined 1Link by 2003 and the consortium of 11 banks registered itself as 1Link as a Private Limited company that was owned by these banks.

These 11 banks now constitute approximately 76% of the banking industry asset base. In 2004, the SBP mandated both the switches, 1Link and MNET, to connect with each other, completing the ATM operability in the industry. MNET later merged its operations into 1Link.

At the time ATM interoperability was achieved, the SBP mandated banks to issue ATM-only cards. These were the proprietary cards issued by banks, not branded as Visa or Mastercard, for cash withdrawals at ATMs only. These were the times when ATM cards used to cost roughly Rs100 annually and could be used for ATM withdrawals only.

It was also around this time that Visa (predominantly) and Mastercard (to a lesser extent) entered the Pakistani market. The history of Visa and Mastercard can be traced back to as early as 1994 when Citibank entered the Pakistani market with the Visa and Mastercard credit cards. While banks were still only issuing proprietary cards that worked only for cash withdrawals, Citibank brought in Visa and Mastercard for customers looking for credit cards.

“It was Citibank that introduced the concept of credit cards in Pakistan and set the stage for Visa and Mastercard cards to make inroads into the country,” says Amer Pasha, former country manager for Visa Pakistan. “People did not understand credit cards back then. They did not even understand the concept of minimum payments and annual percentage rates. The economy started dwindling and credit became expensive. Coupled with the lack of financial literacy, the number of defaulters was very high and credit card growth eventually busted,” he added.

Credit cards have never been popular in Pakistan. If you are a bank customer, chances are that you have received a call from your bank to subscribe to the bank’s credit card. You receive this call because the bank’s credit card portfolio is very small. But you don’t receive any call from your bank to get a debit card. In today’s numbers, credit cards are a paltry 6% of total cards issued, compared to 94% of debit cards in the market.

Having done their research early, Visa and Mastercard both perhaps quickly reached the conclusion that credit cards would never be particularly popular in Pakistan, so they changed their approach and made an offer to the banks that they could not refuse. The banks could brand their ATM-only proprietary cards as Visa or Mastercard branded debit cards, and customers that could previously only use their cards just to withdraw cash from the ATM could now use their cards for purchases at POS machines and online shops.

“The proposition was immediately attractive for the banks. They had already been making a killing on ATM transaction fees, and now they would be able to charge interchange fees if their debit cards were branded as Visa or Mastercard,” a source told Profit.

People in the industry say that back then, it was almost like the banks did not know what was happening around the world and how payment schemes operated. A source disclosed to Profit that international payment schemes had to educate the banks about what was happening in the world with debit cards and how they were being used.

“ATM-only customers reduced the cost of banking at a bank branch but were still an expense for the bank. International payment schemes educated Pakistani banks that if they enabled the same customer to make purchases directly at a shop instead of withdrawing cash at the ATMs, their expense would turn into revenue,” the source said.

“And because they will have an alliance with an international payment scheme, they can charge higher fees to bank customers for the card. So these payment schemes converted banks’ Rs100 only ATM cards into a debit card that banks could now charge their customers at Rs500.”

This is where the banks first smelled blood. You see, it is a maddeningly simple equation. The banks knew very little about how debit cards worked all over the world, so one can only imagine how much the average Pakistani knew or even knows today. Seemingly, there is nothing wrong with the system. The banks giving you a card with an ATM and POS transaction facility is an ideal scenario. The problem, however, is if you are charged a ludicrous amount every year if you are only using it for ATM transactions.

“I’ll give you a rundown of what Visa or a Mastercard’s value proposition is: POS transactions, international transactions, e-commerce transactions, and security,” one of our sources tells us. “And when we talk about security, it is not security for ATM withdrawals. ATM switch is local, that is through 1Link, and the security features are also local and, therefore, not expensive for banks. Visa and Mastercard provide security on POS transactions but they do not charge banks separately for these features. It is covered in the interchange that the payment schemes make. But guess what. Neither international transactions nor POS transactions form the bulk of transactions in Pakistan. So do you now realise what you are paying for?”

Essentially, it is a question of the banks trying to sell cards to customers that they know the customers are unlikely to get their money’s worth out of. Normally, a Visa card or Mastercard card would actually be a decent deal. But given spending patterns, their overall impact makes little sense and PayPak would have changed all of that.

Currently, over 90% of the debit cards in Pakistan branded as Visa, Mastercard, or China UnionPay, another international payment scheme, are used for ATM withdrawals only.

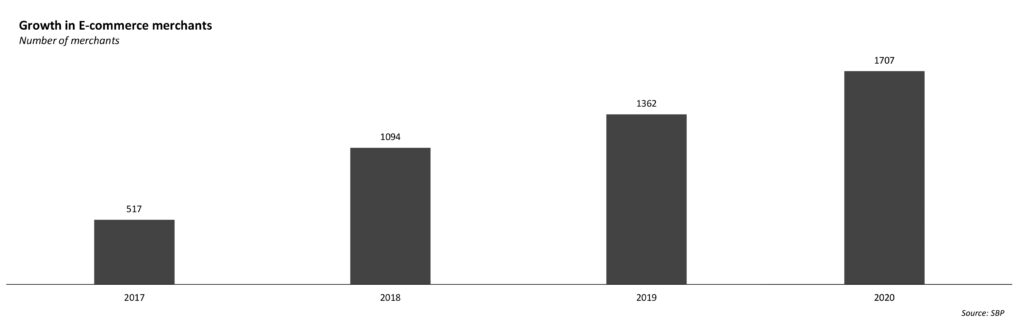

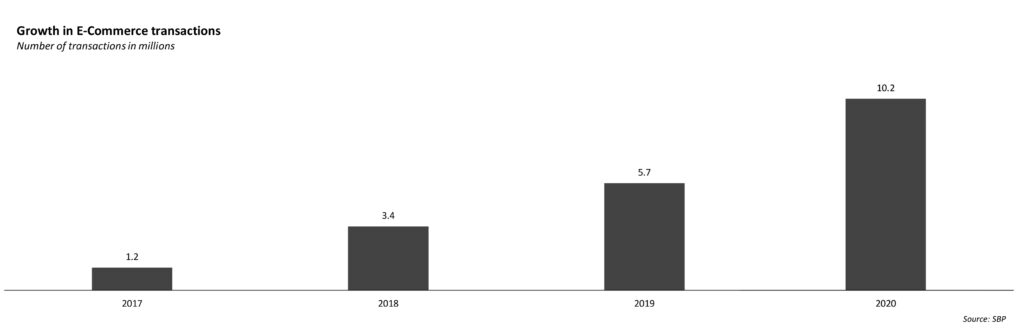

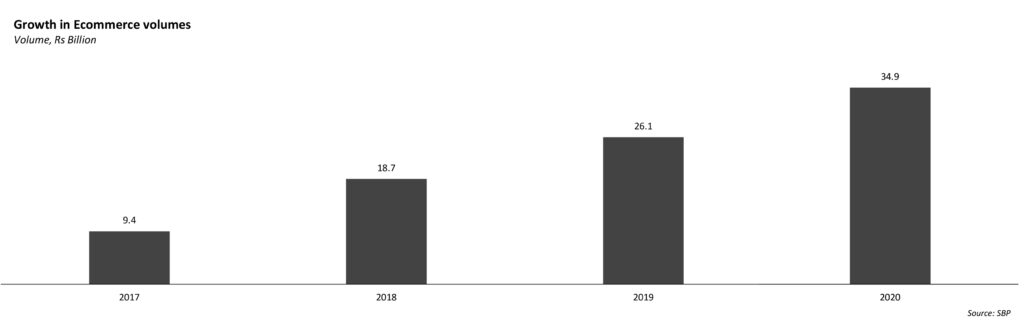

In the year 2020, ATM withdrawals were 94% of the total transactions between ATMs, POS, and e-commerce transactions in terms of volume. Whereas POS transactions were only 5.35% and e-commerce transactions on payment cards were only 0.5% of the overall volume of transactions.

The number of POS transactions using debit cards is even fewer because there are credit cards in the market, albeit in small numbers. The same goes for e-commerce transactions for which credit cards are also used. For further context, 66% of the total number of e-commerce transactions in Pakistan were carried out using credit cards in 2020.

To be fair to banks, they still have ATM-only cards in the market that are charged less but these cards only form 11% of the number of debit cards in the market, according to 2020 statistics from the State Bank of Pakistan.

That is where the problem lies. Ever since the international payment schemes suggested to the Pakistani banks to consolidate ATM-only cards into a single Visa or Mastercard branded debit card, banks have been on an uncontrollable spree to give these cards to people who don’t even need these cards. The hooks they have are the lucrative incentives offered by these payment schemes to market these cards to as many people as possible.

See when you get offered a Visa card, it is pitched in a way that makes it sound highly desirable, and the bank makes the offer even when they know you will not get a lot of utility out of all the features that the card has.

Then again, you might say, the banks are just trying to make money and it is on the customer’s shoulders that they are not using the service. However, for a regulator that has the task of banking the unbanked and underbanked population and promoting financial inclusion to reduce poverty, it does not sit well with the central bank that commercial banks keep on charging heavy amounts in debit card fees and keeping the cost of holding a bank account high. This is where PayPak comes in.

PayPak is born

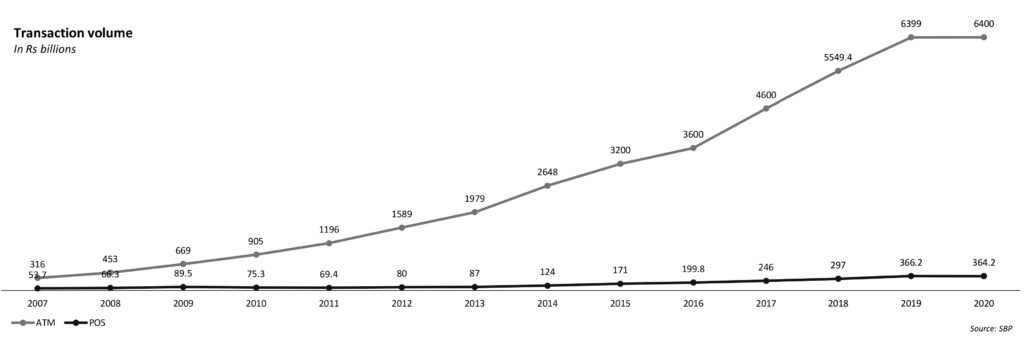

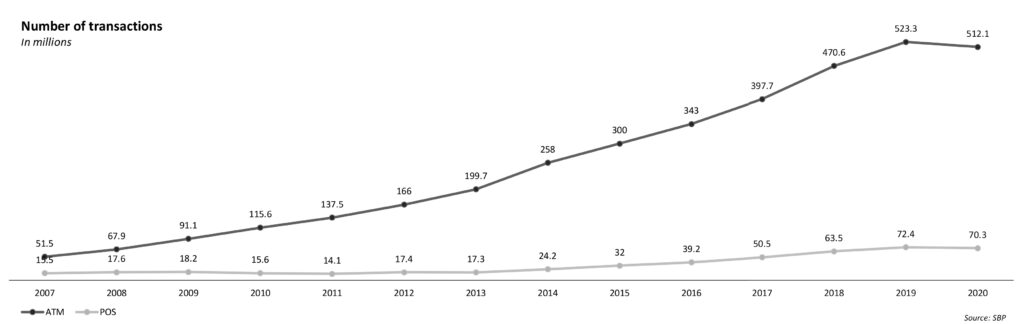

According to 2020 numbers from the State Bank of Pakistan, ATM transactions across Pakistan were 512 million in volume and Rs6.4 trillion in value. POS transactions on the other hand were only 70 million in volume and a paltry Rs 364.2 million in value.

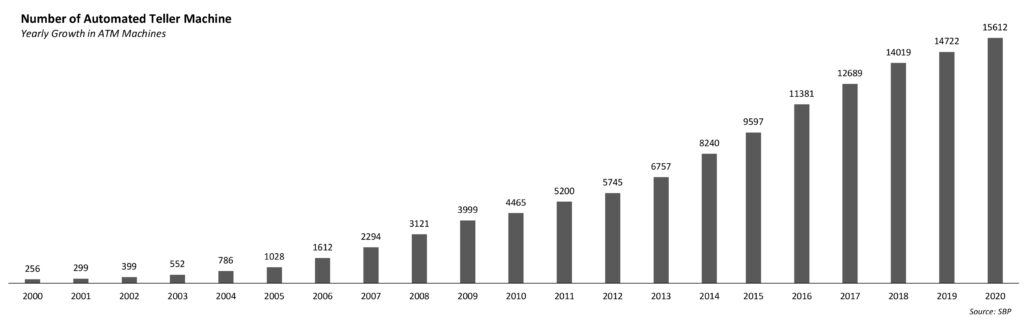

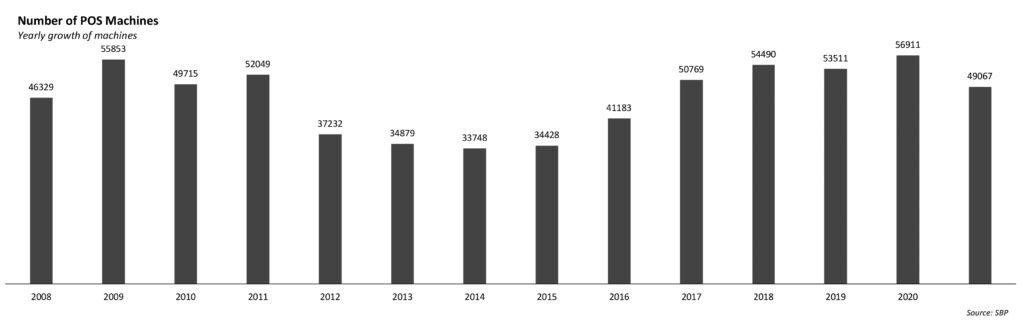

That is 87% transactions on ATMs against only 13% on POS in volume. Whereas in terms of value, ATM transactions formed 94% of the value as compared to only 6% value of the POS transactions. The numbers for ATM transactions have historically averaged higher, much higher actually, against POS transactions. And while the number of ATMs has proliferated steadily, growth in POS machines has remained stagnant over the years.

This is the whole case we have been making up until now. A majority of the population (94% according to our statistics obtained from the State Bank) uses Visa and Mastercard cards for ATM transactions only. This 94% could get the same services they use right now at considerably cheaper rates.

“Here’s what banks do: they won’t even ask you what you want to use your debit card for and give you the card that is priced higher for no utility for the customer. Now it makes sense for banks to give this debit card to someone in Lahore where there are POS machines. It does not make sense to give that card to someone in DI Khan or Bahawalnagar where there even are no POS machines,” our source tells us this time with no shortage of contempt.

This is the problem that the State Bank of Pakistan recognised. That it is not right for banks to give an Rs1,000 or Rs1,500 annual fee debit card to someone who has an ATM use only. As mentioned above, ATM-only cards used to cost around Rs100 only. For someone who has such a limited usage of cards is better off with an ATM card only instead of a branded card, and that would bring the cost of holding a bank account down for the financially excluded poor segments of the population.

Besides poverty alleviation and financial inclusion, various sources in the industry believe that SBP, to manage foreign exchange, did not want dollars flowing out of Pakistan in payments made to Visa and Mastercard. Moreover, the SBP was reportedly also worried about the transactional data that was flowing outside of Pakistan, and in case there was a security breach, it would be difficult to get the money back to Pakistan. However, with a domestic payment scheme with all the transactions being carried out within Pakistan, it would be easier to track and recover funds in case of fraud.

However, a source at the SBP that was directly involved in setting up the scheme and knew the thinking of the central bank at the time dismissed that foreign exchange outflows were ever a concern for launching PayPak.

“On December 19, 2014, the then United States (US) President Obama imposed sanctions on Russia following the annexation of Crimea by Russia and prohibited exports of goods and services to Russia from the US. Among the US-headquartered companies that were barred from operating in Russia were Visa and Mastercard,” our source told us. “Overnight, Visa and Mastercard cards stopped functioning in Russia. That incident worried the policy makers in Pakistan that if the entire payment cards ecosystem was erected on Visa and Mastercard in Pakistan, the ecosystem will collapse in case of a similar contingency as in Russia in 2014.”

This alarmed the SBP, particularly because of Pakistan’s rocky relationship with the United States and the over-reliance on Visa and Mastercard cards. During their assessment, the SBP figured that similar sanctions would not have a huge impact on Pakistan because the ATM infrastructure in Pakistan was locally routed through 1Link. However, the impact would be profound if banking in Pakistan switched to Visa or Mastercard-backed ATM infrastructure in the future with cards only of the same brands in the market.

Now there are people that use Visa and Mastercard cards on POS terminals in Pakistan and there are people that come to Pakistan carrying a Visa or a Mastercard card and process transactions here. The SBP assessment found out that the net exchange was in favour of Pakistan meaning that more people were coming into Pakistan and using their Visa or Mastercard cards than people going out from Pakistan.

“In 2017-18, the assessment was carried out again and the results were almost opposite. More Pakistanis were travelling abroad than those coming into Pakistan. The net difference was an outflow of an estimated $60 million that was going out of Pakistan. This was one consideration but this was not a significant outflow to be the only reason to warrant setting up a domestic payment scheme,” our source said.

Our source further stressed that having a domestic payment scheme was a contingency plan more in the national interest in case there was a deepening in ties between the US and India and if some collaborative sanctions were imposed on Pakistan. That is also the time that assessments at the SBP found out that 1Link was the only contender that could set up the scheme for State Bank. “1Link was subsequently asked to submit a proposal which was approved by the regulator,” he added.

It will come a little later that 1Link as an SBP-regulated entity does not have the muscle to take on Visa and Mastercard and has always needed the central bank to intervene and help prop up PayPak card distribution by the banks.

After these realisations, on April 6, 2016, Pakistan launched its own domestic payment being the 28th country in the world to have its own payment scheme. Pakistan was now in the same league as India which has its domestic payment scheme Rupay, which has now evolved to become an international payment scheme like Visa and Mastercard. Other countries in the same league are Russia, Japan, Iran, Taiwan, and South Korea among the notable ones.

At the inauguration of this scheme, the State Bank Governor said that “Pakistan has moved in the right direction by achieving SBP’s two strategic goals; that is promoting financial inclusion and building a robust and modern payment system.”

So here we have a payment scheme that was launched domestically as a low-cost alternative to Visa and Mastercard because all the charges (which are discussed below) are local, which provide the same functionality as international scheme branded cards, that is ATM withdrawals, which form the majority of transactions, POS transactions, and e-commerce transactions that would be introduced a little later on by the domestic scheme.

And while 1Link and regulators were happy at this success, there were long faces over at the banks, for whom PayPak was a competitor to the Visa and Mastercard card that they had been using as brand names to justify high prices on their cards and were making billions.

Disrupting billions

Let’s get a glimpse of what has been happening. We have banks that have been giving cards to customers that have very little utility against the money that customers pay to use these cards. We have a payment scheme that is theoretically supposed to be cheaper as compared to Visa and Mastercard cards and therefore is supposed to keep the price of debit cards low for customers.

Here are some close estimates as to how much a card costs a bank to issue to a customer. These are official estimates, provided by people in the banking industry, who are familiar with the prices. Firstly, there is a cost of obtaining plastic for a card, then there is personalisation of the card, followed by delivering it to the customer. This cost is similar for all brands be it Visa, Mastercard, PayPak, or China Union Pay. Then are the costs specific to a particular payment scheme.

The costs that are similar for all are for the plastic and printing, embossing, and delivery. Plastic ranges from Rs50 for magstripe cards to Rs1,000 for metal cards, whereas embossing costs Rs30-50 per card. Courier charges vary. Some banks deliver the card to customers free of cost whereas some banks charge the customer for courier services, while others ask customers to collect their debit cards from the respective bank’s branch.

On average, depending on the type of plastic used (and banks do not use high-end plastic on their cards), to deliver the cards to the customer, industry estimates suggest that the card costs the bank around Rs100-150 at this stage.

On top of this, there are the following charges for Mastercard and Visa that are roughly the same for both to keep them competitive: issuance for basic cards is free and there is no annual fee that at least Mastercard charges banks for standard (basic) debit cards. Our estimates are for standard or basic cards only because our assumption is that basic cards are the most popular ones due to the low-income demographic of the country.

From what Profit has learned, for banks issuing international payment scheme cards such as Visa or Mastercard cards to consumers, they have to incur a one-time license cost that ranges from $50,000 to $250,000 depending on the customer portfolio of the bank, and quarterly assessment charges of around $15,000. Depending on the card portfolio of a bank, the average cost per card comes down for banks that have a bigger card portfolio. People in the industry familiar with these prices suggest that average costs for banks stay within the Rs250-300 range for each card that is incurred only once.

For PayPak, on the other hand, there is no licensing or fixed fee. There is only Rs20 issuance fee and an Rs25 annual fee on top of fixed costs of plastic and embossing, whereas delivery charges are variable for banks delivering these cards and are charged by some banks to customers.

Depending on the plastic, the price for each bank for each card may vary and is consequently difficult to estimate. But since there is no fixed dollar-denominated fees in the case of PayPak, these cards are cheaper as compared to Visa and Mastercard. And card prices for different banks justify these. In the year 2018, MCB Bank charged Rs350 for PayPak cards to its customers. Whereas for 2018, Visa was priced at Rs750 and so was Mastercard.

It is also right here that we would like to mention again that banks are overcharging customers for cards that do not cost that much. These costs, such as plastic and embossing and delivery in case a bank does not recover it from the customer, are incurred by the banks just once whereas issuance is charged to a customer once, and an annual fee is charged each year for five years. Debit cards are usually valid for 5 years.

So we are talking about an MCB Bank Visa debit card that incurred a cost of let’s say Rs300 (Rs250-300 is the range that people in the industry say cards on average are usually costing banks), while the customer is being charged Rs750 per year in issuance and annual charge. For the Rs300 incurred in cost, the bank earns Rs4,500 from the customer over the five-year period. And we would like to reiterate again that this is the amount for most of the people that do not have much utility for these cards.

Bank earnings under the head of debit and credit card fees make for a scandal and reflect the extortionist mindset of commercial banks.

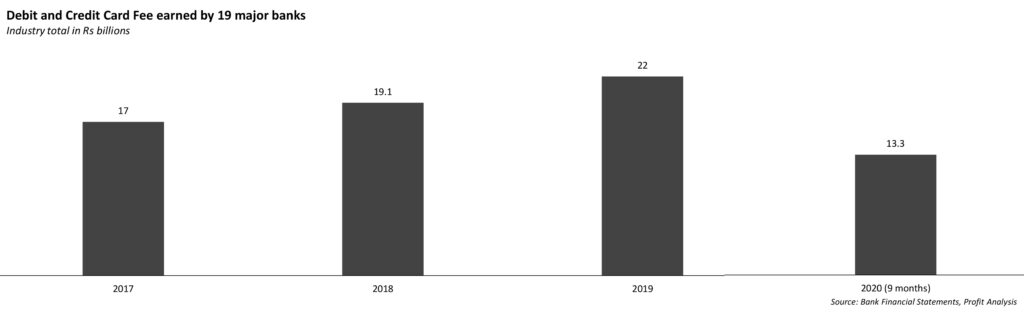

The 19 publicly listed banks collectively made Rs17 billion in credit and debit card fees in 2017, Rs19.1 billion in 2018, and a whopping Rs22 billion in 2019. Now the credit card portfolio of each bank is very small and overall numbers for 2019 suggest credit cards formed only 6% of the market share whereas debit cards formed the remaining 94%. So it is likely that the majority of the bank’s earnings, and that is a significant majority of over 90%, comes from debit cards.

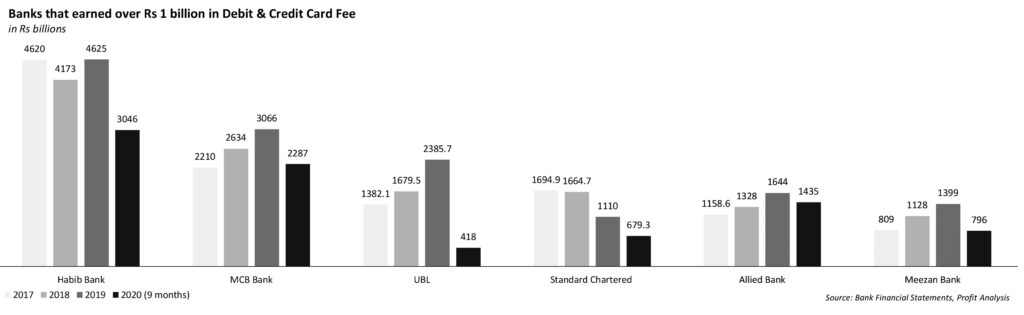

HBL, which dominates the market with 5.5 million cards, made Rs4.6 billion in 2019 in credit and debit card fees, followed by MCB Bank which made Rs3.13 billion, Allied Bank making Rs1.64 billion, United Bank making Rs1.61 billion, and National Bank making Rs657 million in 2019 under the head of credit and debit card fees.

Collectively, these five banks alone made Rs11.63 billion in credit and debit card fees. For the year in review, debit cards were 94% of the total cards and only 6%. Extrapolating on that, assumptively, roughly 94% of the revenue in card fees for these five banks also came from debit cards and only 6% came from credit cards. So according to our estimates, these banks have collectively made approximately Rs10.93 billion in debit card fees alone.

Some more context about the costs banks incur on debit cards compared to what customers are charged in fees for these cards: while analysing financial statements of banks, we found out that almost all the banks had mentioned their earnings from debit and credit cards, which for some banks is the highest income under non-interest income, whereas no bank had disclosed their expenses incurred against the income from debit and credit card fees separately, except JS Bank.

Our perusal of JS Bank’s financial statements validates that against the costs incurred by banks on debit cards, their earnings are much higher. For the year 2018, JS Bank’s earnings under credit and debit card fees were Rs291 million whereas the expenses incurred under the same head were Rs6.6 million only. In 2019, JS Bank earned Rs594.7 million in debit and credit card fees whereas the expenses under the same head were a paltry Rs8 million.

“If a payment scheme on average charges a bank $1 per card, the banks have the right to charge 10 cents on top of that to customers. But here we have banks charging $10 to customers while they are only paying $1 themselves. This practice should be discouraged. The banks should put more of their hard work towards increasing POS transactions,” an industry expert told Profit, on the condition of anonymity.

Sources tell Profit that the rule of the banking industry is that 80% of a bank’s earnings from debit and credit cards come from issuance and annual fees whereas only 20% comes from POS transactions.

Historically, debit card prices have increased for Visa and Mastercard each year at banks. They have increased each year to the point that banks can make the billions in earnings that they are making now.

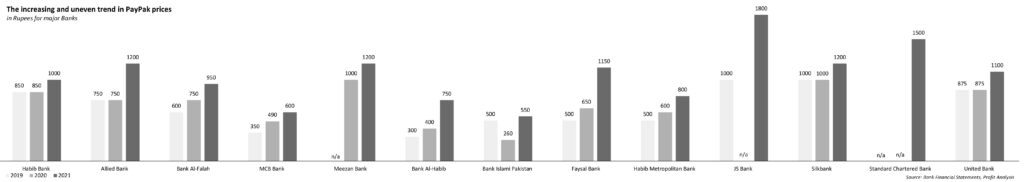

But the aforementioned circular of the SBP changed everything. It is now mandated that PayPak was going to be the default card, that banks had historically priced lower and offered it to low-tier accounts only. For instance, HBL charged Rs500 for PayPak cards in 2017 whereas, by 2020, the price had gone up to Rs850, and has further gone up to Rs1,000 for the year 2021. Mind you that for each card, the customer also has to bear 16% in FED charges that banks collect on behalf of the government. The customer is actually paying Rs1,000 and around Rs170 in FED charges making the total price of card Rs1,170.

When the SBP circular was out, PayPak saw a surge in customers, and cards proliferated. From reaching 3.2 million cards in 2019 from the time it was launched in 2016, PayPak cards surged to 5.5 million in 2020 when the SBP circular was issued.

According to one version of the background story that is popular in the industry, the banks were always reluctant to issue PayPak. For instance, PayPak was treated as the lowest option in the assortment of debit cards. It was offered to level zero accounts, level one accounts, and Aasaan accounts; pretty much the lowest of the lowest. Then they had all the tricks up their sleeves to choke its growth. For instance limits for ATM withdrawals on PayPak cards would be less as compared to a Visa debit card, though there were no technical limitations for the banks and 1Link to allow both to have the same limits.

It was only after the SBP directives in January this year that made it mandatory for banks to offer PayPak as the priority card that things started really taking off. The banks’ reluctance to issue PayPak reflects in numbers too: only 3.2 million cards were issued during the initial three years whereas 2.2 million cards were issued this year alone after the SBP directives. The company, 1Link is poised that the closing number for 2020 would hopefully be 5.5 million PayPak cards in the market.

Visa currently dominates the market with a 40% share, Mastercard and UnionPay have 25% each, whereas PayPak is only 10% in terms of volume of cards in the market, according to estimates provided by an industry expert. In terms of value, Visa owns 50% of the market share, Mastercard owns 30%, whereas UnionPay is at 15% and PayPak is at a tiny 5%.

To be fair to the banks, they do have some reasons to not offer PayPak. E-commerce for one. Since its launch in 2016, PayPak could not be used for e-commerce transactions because it had not signed up with e-commerce payment gateways. But this then warrants a question: if PayPak had a feature limitation, why increase the price of the card each year?

Nonetheless, after a delay of a few years, PayPak has managed to enable e-commerce transactions on PayPak cards, with 1Link management telling us that e-commerce functionality will be launched for PayPak cards at the beginning of 2021.

When we mentioned earlier that 1Link has always needed SBP to increase cards in the market, it is because besides earning hefty issuance and annual fees, Visa and Mastercard offer hefty incentives to banks for promoting the respective scheme’s cards. While international payment schemes charge banks these fees that might look high because of the dollar denomination, they also provide banks incentives and rewards for promoting their schemes under what the industry calls ‘marketing dollars’.

For instance, let’s say if JS Bank manages to issue 100,000 Visa cards in the market, Visa would give a certain amount per card to JS Bank for marketing that card. The amount varies from a few cents to even a dollar depending on the target achieved by a bank. Depending on the cards that are distributed in the market, the amount can run into millions of dollars and it would be the bank’s discretion to use it for whatever purpose it wants to.

It is for this reason that international payment schemes are criticised for driving the market through these incentives. This is what we started off with. The initial conversation with the bank representative exhibited that the bank wanted to discourage the PayPak cards. The bank discouraged the domestic scheme card because it had to promote a card that comes with incentives for the banks in dollars that can run into millions, and it becomes a lucrative proposition instantly for banks to promote these cards.

“Banks act as distribution agents for international schemes. Relationships between banks and payment schemes are exactly that of FMCGs and distributors,” says Mastercard Country Head Atyab Tahir. “Just like an FMCG would give a distributor a commission or discounts to push their products in their market, we give banks incentives and performance bonuses to push our products in the market,” he adds.

“If they do not meet these targets, they don’t get these incentives similar to any other sales organisation. The mindset is that payment schemes come into the market and bribe with these incentives. The reality is that we are just telling banks that you have a certain number of footfall of customers. If you convert them to our cards, we will give you incentive against it,” he further says.

These marketing dollars are also the reason why 1Link has not been able to compete with Visa and Mastercard without the support of the regulator. As a business entity, 1Link is competing with payment schemes Visa and Mastercard that have ‘made it’ in payments globally, and companies making it globally means they are highly competitive.

So when you are competing with Visa and Mastercard, you need to be considered as equals and for banks to take you seriously. 1Link, however, has rather chosen not to be competitive because “they were made to do something that they probably might not have done otherwise, that is launching the domestic payment scheme,” according to their CEO Najeeb Aggrawalla.

All the countries that have domestic payment schemes are not private ventures. In the case of Pakistan as well, the initiative to launch the domestic scheme came from the State Bank of Pakistan and 1Link was apparently the only entity capable of pulling this off. “PayPak was launched totally on the directives and tailcoats of the regulator; the SBP. 1Link did all the plumbing work to start a domestic payment scheme but all the issuance and acceptance occurred because of the regulator’s push,” an official from 1Link told Profit, choosing to remain anonymous.

This perhaps points more towards 1Link management’s lethargy towards promoting PayPak than anything else because PayPak has been delaying launching features, for instance e-commerce payments, which would make it competitive.

When you are competing with global payment schemes, you simply can not choose to sit and wait for the regulator to nudge the market and make it favourable for your business.

It also points toward a lack of interest on part of 1Link management to make PayPak competitive despite spending roughly $3 million, according to a source, to do the plumbing work and start the scheme. 1Link is funded by banks and that is also why it is a little strange that banks that own PayPak are reluctant to promote it. Afterall, if PayPak becomes a success, its profits would go to these banks.

But the conflict here, however, is that 11 banks that include Habib Bank, United Bank, National Bank, MCB Bank and Allied Bank, besides Soneri Bank, Askari Bank, Bank Al Habib, Alfalah, Faysal Bank, and Standard Chartered that own 1Link, form the board of the company, with heads of various departments from each bank as board members.

Heads of various divisions at banks have their own targets at these banks and when you have a board that has members from various departments from various banks, things are bound to be difficult. This is also perhaps why decision-making for management at 1Link would be difficult and time-consuming affecting the performance of 1Link when it comes to PayPak.

“It is not always necessary that the objectives of the board are aligned with the company. Therefore, sometimes, it becomes difficult to effectively manage the board,” admitted 1Link CEO Najeeb Agrawalla. Strangely, however, at the same time, he also says that all board members are experienced bankers from various departments like IT and operations, and all board members are ‘competitive’ which consequently allows 1Link to do what is competitive for payments.

Maybe that is why the regulator also saw and chose to intervene to make things easy at 1Link. It has always been the regulator that has pushed banks to serve the bottom of the pyramid with PayPak cards by launching it, and it has again been the regulator that has mandated again that PayPak be the priority cards for all sorts of accounts, unless customers ask otherwise.

The banks, however, are not ready to go down without a fight, except that this fight is bloodying bank customers rather than banks or anyone else.

Recovering billions

With the SBP guidelines now pushing the adoption of PayPak cards, banks have moved to increase the price of PayPak cards to recover their billions. And the billions did take a hit. For the 9-months of 2020, banks made Rs13.3 billion in three quarters. That’s a little over Rs4 billion per quarter. At the same rate, the last quarter will only add up to Rs17 odd billion for the entire year, which would be Rs5 billion short as compared to Rs22 billion last year.

But banks are not sitting idly by. For the year 2021, almost all the banks have increased issuance and the annual fee for PayPak cards, with some banks increasing card prices insanely. For instance, Faysal Bank increased the price of PayPak cards by over 76%, from Rs650 in 2020 to Rs1,150 in 2021. Standard Chartered introduced PayPak at Rs1,500 this year whereas JS Bank has also priced its PayPak card at Rs1,500 this year.

Branchless banking service provider Telenor Microfinance Bank-backed EasyPaisa has increased the prices as well. EasyPaisa has increased the price of PayPak card from Rs750 in 2020 to Rs1,000 this year in issuance, followed by Rs200 in annual charges each year for the duration card is valid. What is concerning with EasyPaisa is that the other card it offers, which it offers on a priority basis, is one from international payment scheme China UnionPay. With UnionPay, the charges are only Rs600 one-time which include issuance and delivery charges, with no follow-on annual charges for the remaining duration the card is valid.

In contrast, mobile wallet and branchless banking service provider JazzCash has priced PayPak at Rs899 which includes one-time issuance and delivery charges. Each year onwards, annual charges are only Rs299. What was surprising to learn was that JazzCash, backed by Mobilink Bank, is the only card issuer that promotes PayPak as the priority card. It has in fact discontinued Visa debit cards and only offers PayPak cards. JazzCash charges further validate that it is possible for everyone in the payments industry, banks or mobile wallets, to keep debit card prices low for PayPak if they want to.

Pricing PayPak higher makes sense if you want to discourage it. With PayPak prices going as high as a Visa or Mastercard, the customer, with the tricks of the bank representatives, is bound to say no to this card.

There is also a hint of official collusion between banks of keeping PayPak card features limited. Recall how in the beginning, the bank representative stressed that the withdrawal limit on PayPak cards is lower than that of Visa or Mastercard on ATMs. The ATM infrastructure is routed through 1Link which acts as the switch to make withdrawals possible and 1Link management told Profit that there is no limitation at their end for ATM withdrawals on any debit card brand be it PayPak, Visa or Mastercard.

This limitation is created by ATM acquiring banks that do not allow a higher ATM transaction limit for PayPak cards but allow a higher transaction limit for cards that they get incentives on. Acquiring banks are the ones that own the ATM machines at their branches or as standalone, whereas the issuing bank is the bank whose card you use. How much can a customer withdraw from an ATM on a certain card of a certain bank is negotiated and agreed upon between the issuing bank and acquiring bank.

Since all issuing banks are also acquiring banks, because almost all banks have their ATM machines, it all adds up here that banks are colluding to keep the PayPak limit on ATM withdrawals low to discourage customers, and keeping the limits high on international payment scheme cards to make them enticing for customers, and eventually get those marketing dollars.

Here’s where the problem is: the State Bank of Pakistan allows banks to increase charges to keep parity with other banks. So if Faysal Bank is today charging Rs1,150 for PayPak, another bank that charges less than Faysal bank for PayPak card has the right to increase charges to keep parity with Faysal Bank. And banks have further been allowed by the SBP to increase card charges by 10% a year, but can not strictly enforce it upon them. The State Bank as a regulator can only request banks to follow a ‘reasonable’ pricing policy.

The central bank’s fair pricing policy states that “charges should be determined on the basis of cost of doing business plus a reasonable margin. The practice of fixing charges on expert judgment or a percentage rise over the previous year’s charges should be avoided. Where a bank increases its fee by 25% or more for any service, it should document the reasons/justifications and make available the same to the SBP inspection team, when required.”

According to a former official of the State Bank, commercial banks are always somehow able to justify charges. And according to another official, the State Bank can not really do anything about the charges unless a consumer pleads with the SBP that the charges are unreasonable.

An official from the SBP’s consumer protection department that this reporter called as a consumer complaining about the high price of debit cards acknowledged the grievance and directed the reporter to register the complaint with the department’s director via email. In larger interest, this reporter chose to write this article instead.

Editor’s note: For this story, Profit reached out to both Pakistan Banks’ Association, the official body representing the banking industry, and to 1Link Board Chairman Farrukh Iqbal. However, no response was received from either, till the filing of this story.

Please also discribe pros and cons, the evidence provided is not sufficient and miss leading. Please do some proper research. When you publishing any article.

Aren’t banks supposed to be transparent and tell you what offers what so you can decide?

It’s simple logic when you get best internationally usable brand then why to settle for a low Incentive brand that costs same and provides 25% of advantages then visa or mastercard.

Whats the use of having paypak when you can’t use it internationally.

International payments via cards are less than 0.5% of the total transaction. why pay more for the 99.5% of the transactions.

Agreed

Whats the payPak privacy policy, whats its BIN policy? How its fraud engine works. Who are the security guranteers behind this?

But the number of people using their cards internationally is much less. Such lot may continue with the cards of their choice …

True

Partial and insignificant research

Why is the daily transaction limits low with PayPal? Does that have to do something with money markets and interbankbpayment settlements rates?

Biggest draw back of PayPak debit card is that it is not Visa. You Cannot use it for Online Shopping not at all…

Author has not done proper research. There is also UnionPay which is an international payment scheme and is even cheaper from PayPak. Why should banks offer a debit card that is not accepted internationally nor online. All international payment schemes spends a lot to offer discounts and other value additions for its card members. PayPak, which is a 1Link ( private company) card has offered nothing and when they do it, they recover it from the banks. No reason for the banks to promote PayPak.

This does not go with all banks one of bank i have account with recently informed through SMS to select at free will whether PayPal or master card by particular cide . & their will not be replacement charges for that aswell.

Ok

Yes

I guess both have their own usage & customer base. It would be helpful if you can share a side by side comparison of visa & PayPak. Also, please share stats about how many customers are using visa vs PayPak even better to give breakup of customers with avg balance in ranges of less than 100k, upto 500k upto million & more than a million.

Wasted article. Paypak cannot be used internationally and neither on POS machines which are integrated with visa or mastercard while u pay the same fees as normal classic. That is probably why salespeople give the best available option.

The reviews are 100% on truth, I am running in my accounts in 5 banks. And not a single bank is ready to issue paypak debit card. Even in HBL last year, there has been Top much clash between me and operation manager Mr zulifqar HBL code 0445.on this issue. I submitted complain to HBL Karachi head office but all in vain. My demand was this HBL bank has introduced Paypak on its website then why not issuing to its customers physically. Manager was saying we only issue Classic visa card.no any paypak is concept here.

Same reply was by ABL branch staff. They refused clearly that no any paypak in ABL books. Then I submitted complain to head office then they issue paypak. Means no any bank is ready to issue it. SBP should notice about it strictly.

ALL THE BANKS R LOWER CLASS

I am also a banker but u are right when ever I give union or PayPal the account officer denied me to not go give any debit card except visa.

The major reason behind PayPak not being offered is not only that its not accepted internally also it does not offer any eCommerce transactions. In the recent times where eCommerce increased many folds but this Payment Scheme does not offer the basic functionality. Even if they offer then again it would be local what about FB, YOUTUBE, ALIEXPRESS and other sites.

Above all it will only act as a ATM card as it’s POS acceptance ratio is also very low.

If customers are willing to buy visa master r whatsoever card then why are you saying this and why are you pressuring

The reason why banks are offering paypak cards is the annual fee which is quite less than visa fee banks have to pay as per their terms and conditions with international companies. It is true that customers are experiencing diffucultes while using paypak cards but on the other hand banks cost is lesser and income is significant.

Its not an international payment vendor. So its obviously rubbish. Dont need a bank to tell me that.

PTI just wants to keep money from going out. Thats all. Its a violation everyones civil liberties in the name of democracy.

Instead of being internationally competitive this govt thinks it can manage the same level of development locally without paying any attention to the socio economic and social welfare retardation evident in the Country.

Skewed priorities.

Requird Debite Card

Thank you

Unfortunately Payment System function of SBP is dormant. Banks will promote only those card which gives them big profit. VISA and mastercard charges interchange fees of about 2-3 percent in Debit Card also. Banks get their share of profit. SBP must take steps similar to taken by EU SEPA and now EPI. I worked as Director Payment Systems from 2004 to 2010 and know the internal and external factors hampering digitalization of economy. PM must take Digitalization of Economy directly under him.

Visa and MasterCard don’t charge interchange, they set interchange – interchange is earned between the banks. It’s in Visa and MasterCards interest that interchange is set at the correct level to incentivize and drive digital transactions, if it’s too low then issuers make no money and don’t drive volume, if it’s too high then merchant have to pay too much commission and don’t accept cards. Is PayPak interchange (or merchant comm) regulated and if so is there any commercial incentive for banks? Banks will also not shut their Visa and MCW programs down, and depending on the mix will still pay fixed cost, so PayPak introduces a potential duplicate scheme, more cost to manage this with less commercial incentive.

Pakistan is going backwards. Alll imports are banned. Nothing is available in the market. Pakistani brands of food stuff is low quality. Imran should open the economy completely let the market forces take care of the economy

Let the market forces prevail please and not misconceived agendas or misadventures that will land us back to the Stone Age again! Banks and consumers have the right of decision and choice any move to block them will be a disaster and disservice to the country.

My two cents : The goal should not be to sell Pay Pak and tolerate ATM usage , the mission should be to promote POS, e-commerce and embrace digitization to grow tax base beyond the salaried citizens. To do this banks, EMI have to invest billions in growing acceptance and funding expensive merchant discounts to build awareness and repeat usage.

Banks can’t deliver this on their own, unless Government plans to instal ATMs with limitless supply of Ca$h to fund this cause or simply bank / emi convinces payment scheme to sponsor their digital ambitions. However for the later, Policy makers and tax authorities have to welcome and compliment the banks and partners efforts by introducing legislation or tax concessions on retail payments that will help optimize private and foreign investments and bring more citizens in the formal economy.

Even if Pak Pay did find a pot for such investments, it would fall short versus investments and innovations foreign schemes bring on. The road to include every one is not only a progressive move but far more economical and quicker when governments are not required to bear the expensive financial brunt..sooner we understand this the better.

such a great post

Fantastic research, I learned a lot from it.

Thanks for writing it. 😍