As soon as you click on the link for Al Baraka Bank’s website, the first thing you will see are two ornate, and very Islamic-looking doors parted slightly, with light bursting through the crack between them. “Opening the doors of Baraka,” the caption to the picture reads. Baraka, of course, means blessed, and if it was not clear from the name, the website is a pretty clear giveaway that the bank is an Islamic bank.

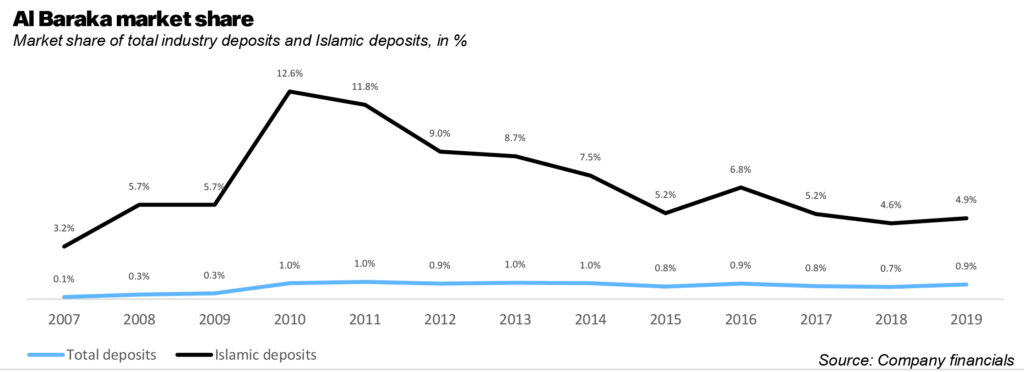

And while the bank may claim to offer its customers light-filled, Sharia-compliant banking services, its own historical trajectory has been anything but blessed. For one of the oldest Islamic banks in the country (having been around in some iteration since 1992), it is also one of the smallest banks in the country, commanding only 0.9% of total industry deposits in 2019.

This paltry share in the market is even more surprising given the rapid success of Pakistan’s Islamic banking sector. The number of Islamic banks in Pakistan have grown in the last two decades from just two at the start of the 2000s, to now, twenty-two. Similarly, Islamic banking constituted just 0.8% of all banking deposits in 2003, but accounted for 18% of total deposits in 2019. The spectacular consumer interest in Islamic financing has changed the trajectories and size of banks that offer Islamic finance. Undoubtedly, the greatest beneficiary has been Meezan Bank, which in 2019 was the sixth largest bank in terms of deposits.

One can see this growth reflected in deposit numbers as well. Between 2003 and 2018, deposits in the conventional Pakistani banking system grew at an average rate of 20.2% per year, according to data from the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), from Rs1.8 trillion to Rs13.4 trillion. That looks impressive, until one looks at the growth rate of the Islamic banking sector: during that same period, deposits at Islamic banks and Islamic banking windows of conventional banks grew at an average of 65.1% per year, or from Rs14.4 billion to Rs2.2 trillion.

Banks like Meezan bank were started in 2003, giving Al Baraka bank a whole decade of a head start. And yet, despite two acquisitions in the last two decades, the bank has struggled to gain a footing in the banking sector. Why was this bank not able to capitalize on being one of the first Islamic banks in the country? If you are one of the people responsible for the bank at either Al Baraka Bank Pakistan or the Al Baraka Banking Group, they are difficult questions to face up to. Al Baraka Banking Group did not respond to request for comment, while Al Baraka Bank Pakistan declined to comment. But results often speak for themselves, and we were still able to piece together what happened.

History of the bank

The bank’s story begins in 1991, when the Al Baraka Banking Group decided to set up shop in Pakistan, under the Al Baraka Islamic Bank (AIB) Bahrain. It would be quite some time later in December 2004 when a separate entity, Al Baraka Bank (Pakistan) Limited, was incorporated as a public limited company, and granted an Islamic banking license in 2007. In October 2010, Al Baraka Islamic Bank Pakistan (AIBP), the branch operations of Al Baraka Islamic Bank (AIB) Bahrain and Emirates Global Islamic Bank (Pakistan) were merged. What really happened is that Emirates Global Islamic Bank ‘became’ Al Baraka (the available financial statements for Al Baraka stretch back to 2007, when the bank was still known as Emirates Global Islamic Bank).

The bank is still a subsidiary of the Al Baraka Banking Group (ABG), which is a Bahraini company listed on the Bahrain and Dubai stock exchanges, along with NASDAQ. The authorized capital of ABG is $2.5 billion, while its asset base exceeds $26 billion and total equity stands at $2.3 billion. The group has banking units and representative offices in 17 countries, in Europe and Asia, and a network exceeding 700 Branches in Bahrain, Turkey, Jordan, Pakistan, Egypt, and Algeria, to name a few.

In 2016, the ABG group decided to take another shot at expansion, and merged the bank with Burj Bank. It was another Islamic bank that had been the sixth Islamic bank in the country, beginning operations in 2007. At the head of operations throughout was one man: Shafqaat Ahmed. CEO since the bank’s inception all the way up to 2018, when he finally handed the reins over to Ahmed Kidwai in 2018, who had himself been part of the bank since 1996. In particular, Ahmed Kidwai had overseen the branch expansion at Al Baraka bank.

A middling history at best

There is one thing that has to be said, Al Baraka Bank was definitely not the victim of too many management changes. But it appears as if the unflinchingly stable management did not quite translate into good fortunes for Al Baraka bank. Profit took a look at the bank’s financials to get a measure of the bank. The first trend that sits up is that the bank’s deposits have actually been steadily increasing since 2007, when deposits stood at Rs4.5 billion. In particular, deposits grew at nearly 140% year-on-year in 2008, and at 227% year-on-year in 2010, in the early days of the bank’s expansion. Deposits crossed the Rs50 billion mark in 2010, and the Rs100 billion mark in 2016.

And yet deposits actually fell the next year by 8.7% to Rs97 billion, before bouncing back up again to Rs 129 billion in 2019. If one looks at the deposits as a share of the total deposits in the banking industry, Al Baraka’s share since 2007 has never crossed 1%. It has only hit this lucky number in 2010, 2011, 2013, and 2014: in every other year, it has hovered below.

Still, despite non-existent market share, at least deposits have grown at a faster rate than the industry rate. One can also see this in the compounded annual growth rate for deposits for the five year period between 2015 and 2019: for Al Baraka, that figure is at 12.6%, which is higher than the industry average for the same period, at 9.5%. If one looks at deposits as a share of the total deposits in the Islamic banking industry, the story is a little better. For instance, at its peak in 2010, the bank commanded 12.6% of all Islamic banking deposits. But since then, its market share has decreased, to just 4.9% in 2019.

For the most part of the decade, particularly between 2011 and 2016, the net interest income has hovered in the ballpark range of around Rs2 billion. But net interest income shot up 2017 onwards, crossing the Rs3 billion, Rs4 billion, and Rs5 billion mark each year. The same goes for non-interest income, which between 2017 and 2019 shot up to the Rs1 billion mark. All in all, this has meant much higher revenues than Al Baraka has been used to seeing, hitting the highest it has ever been in 2019, at Rs6.4 billion.

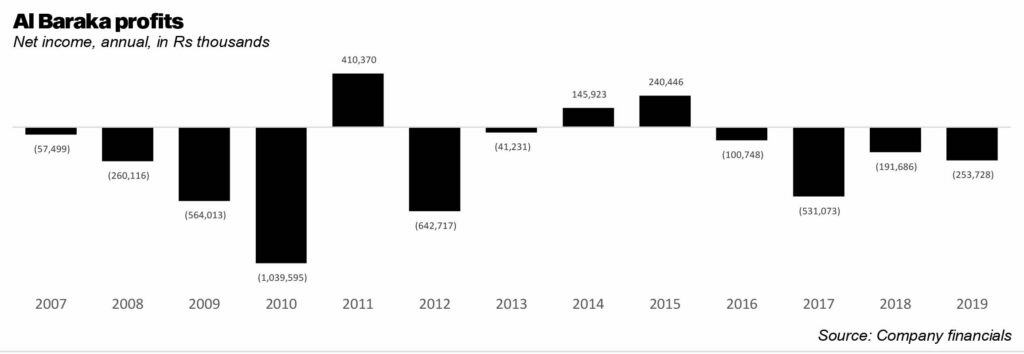

And yet, the higher revenues have not translated to profits. Between 2007 and 2019, the bank made a loss every single year except for 2011, 2014, and 2015. The losses were particularly great in 2009 and 2010 (Rs564 million, and Rs1 billion respectively).

The return on equity, or the net income divided by shareholders equity, has been abysmal. For the most part, Al Baraka has struggled to maintain a positive ROE (a high ROE is an indication of financial health, or how effectively management is using a company’s assets to create profits). While the bank suffered from an appallingly negative ROE of -16% in 2009, and -17% in 2010, it bounced to 6% in 2011, which is also the highest ROE the bank has ever experienced.

In absolute terms, the bank’s non performing loans increased, particularly in the last five years, climbing from Rs4 billion in 2015, to Rs9.2 billion in 2019. When one looks at the ratio of the non performing loans to gross advances, the ratio has been consistently higher than the industry average every single year in the last decade except for 2011, 2013 and 2014. The greatest discrepancies were seen in 2012 (19.3% compared to the industry’s 14.5%) and 2019 (12.8% compared to the industry’s 8.3%).

The loan-to-deposit ratio has also been quite high (the ratio is used to assess a bank’s liquidity). In the years 2015, 2017 and 2018 particular, the bank’s LDR was higher than 70%.

According to Faizan Kamran, research analyst at Arif Habib, “Over the last couple of years their loan book appears to be quite stressed which is affecting their profitability. So their infection ratio over the last three years has averaged out at 10% which is above overall industry average. Peers Meezan and Dubai Islamic have average infection ratios of 1.5% and 2.1% respectively over the last three years.”

According to Kamran, this has a spillover effect. “So the non performing loans are forcing the bank to book hefty provisioning expenses which is affecting their profitability and forcing them to book losses,” he said.

Al Baraka has also suffered from a higher cost to income ratio. That ratio is a measure of how efficient a bank is. The lower the cost to income ratio, the better it is for a bank’s performance. But according to Kamran, Al Baraka’s cost to income ratio was 81% in 2019 and 90% in 2018, significantly higher than the sector average of 65% and 63% respectively. This prompted the bank to take some cost cutting decisions particularly in 2019. As an example, a source said the credit department at Al Baraka bank had been reduced to minimum possible staff.

Analysis

Because Al Baraka is not a listed bank, it is not covered by most brokerage and investment houses. However, a good metric of figuring out if Al Baraka bank is doing well, is comparing it against the benchmark of other, listed Islamic banks.

According to Fawad Basir, senior research analyst at Topline Securities, a useful benchmark for what an Islamic bank could be is Meezan Bank. “Since its inception, it has grown tremendously. Part of the reason it has done so well, is because of its stable management. Secondly, it has been able to capture the concept of religion in Pakistan, which has resonated with the nation.”

According to Basir, the State Bank of Pakistan regulations on the minimum deposit rate does not apply to Islamic banks. This means that if costs are kept to a minimum, an Islamic bank has the chance to grow rapidly, which will result in higher profitability.

It is a view echoed by analyst at BMA Capital, who said that Islamic banking was nearly pioneered by Meezan Bank, which was one of the first banks to capitalize on the term. It outperformed the conventional banking space because it was able to tap into a market segment that was previously not using conventional banking, and thus tapped into unrealized deposits.

And yet, this is not the case for Al Baraka bank.

First, there is the matter of a figure not mentioned yet: the number of branches a bank has. According to Saad Hashmi, executive director of BMA Capital, “a bank’s growth is correlated to its branches.” He further said that banks, particularly in the last five years, have embarked on a massive branch expansion. For instance, Meezan Bank banked on its branches for added visibility and name recognition.

It is a view echoed by Fawad Basir, senior research analyst at Topline Securities, banks in Pakistan rely on traditional brick and mortar branches for growth, as digital banking has not yet caught on at a mass level. According to him, Meezan Bank for instance opened around 70 to 80 branches in 2020, and is targeting around 50 to 60 branches this year.

A notable exception to this has been Standard Chartered Bank, which in recent years decreased the number of branches it had. But this was partially by design. Standard Chartered has the unique position of being the only foreign bank left in Pakistan, and caters to a niche audience it has built over the years of typically high-end clients. The bank also has high brand name recognition, having existed in the country from before independence.

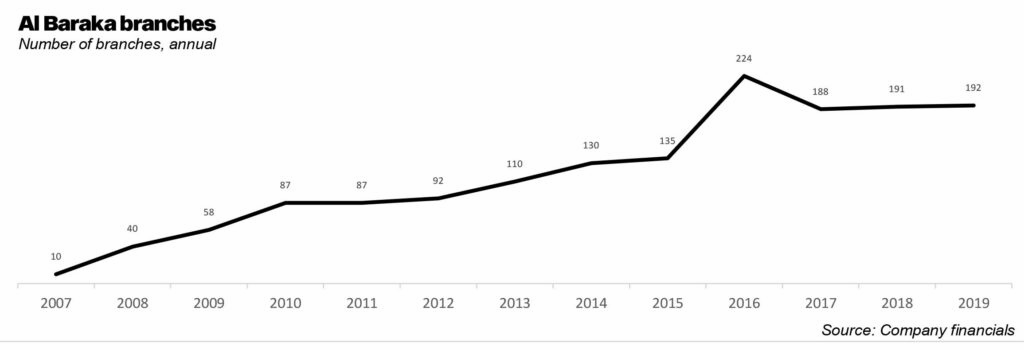

These are not qualities that Al Baraka Bank has going for it, considering that it has a relatively newer bank. It also has uneven growth. In 2007, the bank only had 10 branches across Pakistan. This increased to 87 by 2010, but then hovered in that ballpark range until 2014, when it grew 18% year on-year to 135 branches. It then added more branches to reach its total of 224 branches in 2016, the highest number yet. But then, the very next year, it closed those branches and merged others, falling to 188 branches. In 2018 and 2019, growth was anemic, with only four branches being added in two years.

The number of branches in an area, and the corresponding presence, matters. As the analyst at BMA capital pointed out, “If I want to open an Islamic bank branch, then there gallis away from my house I’ll be able to find a Meezan bank.” Alternatively, a customer will have to hunt and find their closest Al Baraka branch. A bank’s PR and ‘presence’ also means that Meezan Bank can more readily convince the customer of their new offers, and offer a plethora of Islamic banking services. Al Baraka would have a tougher time doing so.

But fundamentally, someone is in charge of deciding how many branches are opened in a year. And that leads to the second problem area: strategy, or lack thereof. As some analysts point out, often, a bank decides to become ‘comfortable’ i.e that some banks are simply okay with the level that they are at. According to one analyst, it could be that Al Baraka was not strategized to grow, and was probably comfortable with their clientele, and are happy in their space. Similarly, Basir pointed to Samba Bank Pakistan as an example of a bank that was operating in a niche market. “Samba bank has remained a small bank operating at a small pace, and its sponsors seem ok with that. Al Baraka sponsors must also be ok with the progress so far.”

Could the sponsors be behind Al Baraka’s performance? Typically, problems with sponsors ar exacerbated when sponsors are foreign-based, or foreigners (to note, this is not something specific to Al Baraka: after all, Habib Bank’s majority stakeholder is Swiss-based entity Aga Khan Fund For Economic Development (51%), while UBL is owned by Sir Anwar Parvez, UK-based Pakistani and founder of the Bestway Group).

Who is to blame? One camp believes that the principal sponsors had not sponsored the aggressive growth of the bank, despite Shafqaat Ahmed’s requests, and had also simply not given support or equity. For this, one has to turn to Adnan Ahmed Yousif, who has been the president and CEO since 2004. While the group did well under him (Al Baraka Group grew from its initial asset size of $ 4.1 billion with 131 branches to $26 billion and around 700 branches in 2020), that does not mean the Pakistan division did well. This is also more surprising, given that Yousif was also the chairman of the board of Al Baraka Pakistan

The other camp believes that in fact the sponsors had been keen on expansion (and so had Shafqaat Ahmed), which is why the two acquisitions took place in 2010 and 2016 respectively. And yet it was Shafqaat’s leadership that had bungled up matters, despite the two mergers. For some organizations, the leader takes on paramount importance. Witness the rise of Meezan Bank, which as this magazine has already pointed out, relied heavily on the guidance of Irfan Siddiqui. Yet a former employee of the bank said that Shafqaat Ahmed did not have what it took to lead the bank into a new era of growth, and that he was simply not aggressive enough.

When contacted, Shafqaat Ahmed said the following: “I remained the CEO of Albaraka Bank for more than 25 years, and enjoyed the full support & backing of ABG and its leadership in all spheres including my leadership style, so much so that they put me on the board of the bank as a director after my retirement from the bank. During my tenure, and with the full support and guidance of ABG, we acquired two Islamic banks in Pakistan.”

So, there you have it. At this point, conventional banks’ Islamic banking windows have grown larger in number than Al Baraka’s bank branches. Making a profit is not a sin; and yet Al Baraka has not seemed to have gotten the memo.

Either way, the past is over with. In 2018, as mentioned before, Ahmed Kidwai became the new CEO of Al Baraka Bank Pakistan; and in 2021, Mazin Manna replaced Adnan Ahmed Yousif as the Group’s new president and CEO Chief Executive, pending approval from the State Bank of Bahrain. Whether the new team will be able to help things turn around, only time can tell.

Clearly the fault lies with both the BoD as well as CEO. Without any vision & strategy, both were / are comfortable at the existing size of the bank. Not just Meezan, but all other Islamic Banks and windows have grown bigger than Al Baraka in Pakistan. to grow, you need to make an extra effort which is clearly the CEO was willing to make. Unfortunately the CEO kept his position because he had the right ‘arab’ connections as this was more important than making money. Cannot think of a single private entity in Pakistan where the CEO remained at the helm of a loss making entity for 25 years?

And to some extent, still maintains to hold sway over the Banks future..

If you want a case study of absolute inefficiency in leadership, look no fuurther.

Looking at Their balance sheet and approach towards business today even, rest assured, they will remain the same as long as they are in business in Pakistan. No strategy, no vision, and absolutely no team and teamwork. Perhaps Arabs needed some place to sink their money and they have it in shape of this entity in Pakistan .

Well the reason is simple. No banker in Pakistan wants to go to Al Baraka. When you don’t attract the top talent in any field within banking, and all the posts are filled with old bankers that got the job through connection and are just happy to mark their presence day in day out without doing any work, then the result is obvious. Bank Al Baraka is the exact place an old school banker would go to complete his retirement years.

Recently the have announced their new vision & mission statement. But actions should speak louder then just added new para on their domain. Simply the management does not have that foreside to grow bank with zero strategy.