Most business students in Pakistan are familiar with the phrase “first mover advantage”. The concept is simple enough: if you want to succeed in a business, be the first one offering the product or service in question. It is a rule that works well enough in most industries. Just not in tech.

In the tech industry, entrepreneur-turned-venture capitalist Peter Thiel (co-founder of PayPal and earliest investor in Facebook) popularised a different concept: last-mover advantage. The idea is counterintuitive at first blush, but important to understand: in an industry like tech, where the landscape keeps evolving, the business model most likely to succeed is the one that comes in after the failed business models have already been tried.

In other words, the one to succeed is the one who comes after others have already shown what does not work, so that they can then figure out what will work. And of course, if that is what it takes to succeed, then moving first is not an advantage. Moving last is.

Because in technology, there is not one but two simultaneous sets of competition that are taking place. The first is the competition between the technology companies themselves. The second, often ignored but much more important competition, however, is that between the new business models and the old way of doing things. For a tech company to build a truly valuable platform, they need to win both.

If that is the case, what then to make of Daraz, Pakistan’s largest traditional e-commerce marketplace, one that was founded by the Germany-based Rocket Internet, but was acquired by Alibaba in 2018. Can it stay atop this growing sector of the economy, or will it become one in a long line of companies whose business models had to fail in order for the market to discover the one that will be successful.

In this story, Profit takes a look the evolution of e-commerce, both in Pakistan and outside the country, to gauge the direction of the industry and to assess where the market might be heading. We then examine Daraz’s business, its current and potential future competitors, to arrive at a view of whether Daraz can maintain its market-leading position.

For this story, we gained unprecedented access to Daraz Pakistan’s financial statements, which gave us an in-depth look at the company’s financial health and the success of its strategy. We also interviewed Bjarke Mikkelsen, the global CEO of Daraz and Ehsan Saya, the managing director of Daraz Pakistan.

The evolution of Daraz and Pakistani e-commerce

We will skip the usual history lecture on how Pakistan’s e-commerce market evolved because it is not much of a history. For a long time, nobody sold anything on the internet in Pakistan because we are an exceedingly low-trust society and we all listened to our risk-averse uncles who said, “nobody buys anything on the internet in Pakistan”.

Then a few brave souls decided to try anyway. There was HomeShopping.pk and Liberty Books and then a few others jumped into the fray. But the market was virtually nonexistent until Germany’s Rocket Internet jumped into the fray and launched Daraz.pk.

Rocket Internet is a company whose business model is relatively simple: take the best ideas of internet companies in the United States and Europe and try to recreate them in emerging and frontier economies, eventually selling those clone businesses to the original companies in advanced economies or anyone else who might be willing to pay up.

Daraz.pk was Rocket Internet’s first investment in Pakistan and started in 2012. Rocket began recruiting people with foreign college educations and LUMS, the kind that would be just as home at a Silicon Valley startup as they would in an office in Karachi. Rocket made it clear that they wanted to move fast, and wanted people who would be fast learners.

Daraz followed the Amazon strategy for Pakistan: it started off with one vertical before expanding its offerings. In the case of Amazon, it was books. In the case of Daraz, it was apparel. Daraz started offering clothing and shoes from well-known brands to Pakistan’s affluent upper middle class. And like Amazon, Daraz started off as a direct seller first.

Within the first three years, the company grew its revenues substantially. By the fiscal year 2015 (Daraz’s financial year ends June 30), the company had Rs491 million ($4.9 million) in revenues in Pakistan. That is when Daraz decided to substantially expand by opening up its platform to third-party sellers, allowing them to sell their products via Daraz.

This was an era when the Facebook and Instagram-based sellers had just started taking off, and Daraz wanted to capitalise on that opportunity by having as many of them move over to its platform – and pay it a fee for the services of listing and, in some cases, fulfillment services – rather than continuing to operate independently.

In many ways, they are still a big part of the company’s competition. “If you look at our biggest competitor its people that sell on Instagram and Facebook. And unfortunately, there is very little governance on those platforms. You could order something online from one of those and you could get scammed which really hurts [the e-commerce industry],” said Ehsan Saya, managing director of Daraz Pakistan, in an interview with Profit.

That, in turn, gets to the heart of the challenge of growing an e-commerce business in Pakistan: we are a low-trust society, which means that people remember scams much more than they remember a good experience. That has implications for the e-commerce growth model.

Marketplace: solving the trust vs growth trade-off

One of the ways in which in which Daraz differed from the Amazon model was the speed with which it decided to create a marketplace. Whereas Amazon did not create a marketplace until its seventh year of operations, Daraz did so in its third year (2015), and that move was likely responsible for turbocharging the company’s growth.

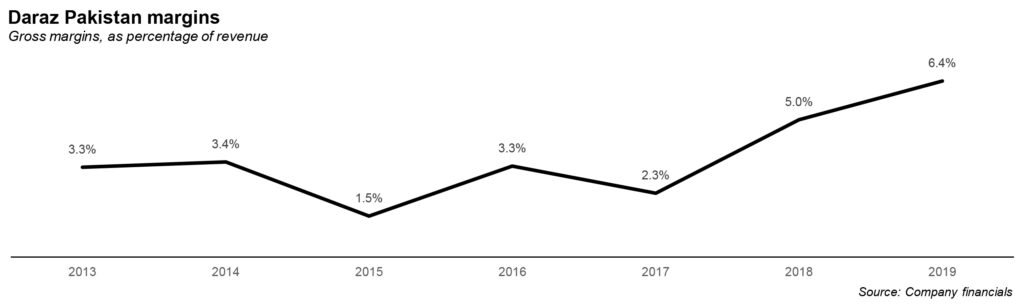

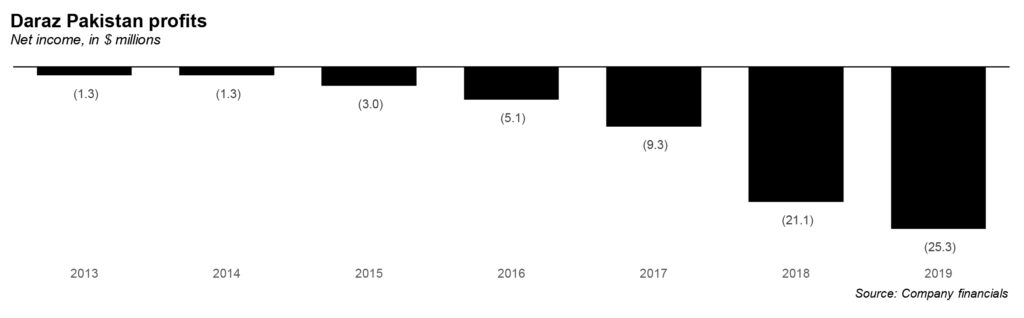

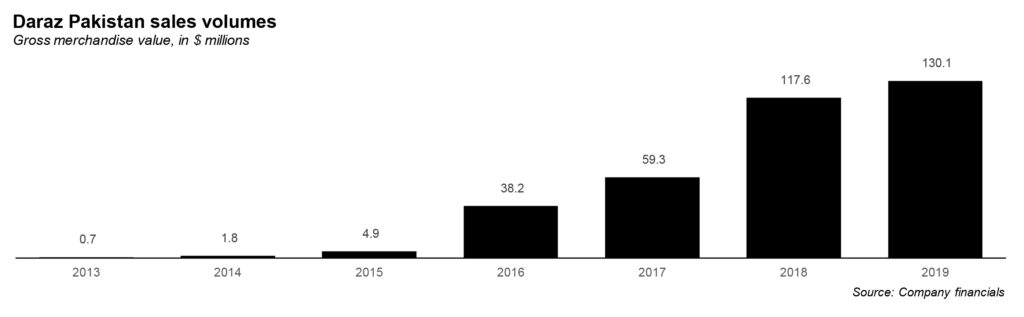

There is no question that the marketplace resulted in significantly faster expansion of the size of Daraz’s platform. From just $4.9 million in 2015, the company was able to grow its gross merchandise value (GMV) to $118 million in 2018, growth that came almost entirely on the back of its third-party marketplace business. At this point, Daraz is really an e-commerce platform with a small direct sales business.

Those numbers alone seem to justify the pivot away from direct selling to the platform business. That Daraz can earn substantial revenues from opening up its platform without having to tie up large amounts of its capital in inventory (that capital instead comes from the smaller third-party sellers using the Daraz platform) seems like an excellent move to turn what would otherwise be a capital-intensive business model into a capital-light business.

However, it comes at a cost: Daraz has far less control over the behaviour of third-party sellers, some of whom engage in fraudulent or otherwise unethical activities. Now, every business faces at least some fraud, but in a low-trust society like Pakistan, the stories of that behaviour travel fast, despite Daraz’s best efforts to curb them and create policies to stamp them out.

“If something goes wrong and the problem is not resolved, no matter whose fault it is, the customer will blame the e-commerce business,” said Hamaad Ravda, the former chief marketing officer of Daraz.pk and one of the leading architects of Pakistan’s e-commerce industry, in a 2018 interview with Profit.

That means that Daraz has a trust perception problem, despite actively putting in place several policies to combat bad behaviour on its platform. That trust deficit is a key area of focus for the management, and one on which they say they have been able to make some strides.

“We do definitely [have a trust problem] and over the last 12 months we have made huge progress,” said Bjarke Mikkelsen, global CEO of Daraz, in an interview with Profit. “There are a couple of different things that we track but one of them is our customer satisfaction score. If there is an interaction with customer through customer service or anything, afterwards we always ask the customer if you are satisfied with the solution and that is the most immediate impact. And here we have made huge progress. In 9 out of 10 cases, customers are satisfied with the interaction they have with Daraz. We still want to get this higher but 9/10 is a big improvement over the last 12 months.”

“And then the second is the NPS, the Net Promoter Score, and over there as well we have made huge progress. We are now at around 50 for the NPS and we want to bring it around to 60+ in the coming year. That is also a massive improvement even over the last 12 months. We are making great progress. I am not worried about getting there. And the word is also spreading. It takes up a little bit of time to bring brand perception to also catch up to the significant investments we are making to service quality.”

Net promoter score is a measure of how much a company is trusted and liked by its customers. It is the result of a survey of customers, who are asked to rate their interaction with the company on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being the best and 1 being the worst. The net promoter score is then calculated by subtracting the percentage of customers who rated the interaction 6 or below from the percentage of customers who rated the interaction a 9 or a 10.

Daraz has attacked the trust issue in a couple of different ways: it has tried to pay attention to customer complaints more, and it offers a purchase protection program where a dissatisfied customer is entitled to a refund. “We’re the only player we have to push the narrative to the customer that no, look, you are protected. If something does go wrong, we have your back and we will fix it. Unfortunately, we are the only player that is pushing the narrative,” said Saya.

This does not always work out well in practice, however. Social media is rife with customer complaining about how Daraz’s refund policies are slow and difficult to navigate. To their credit, the management is aware of those complaints and says they are working to improve upon customers’ perceptions.

“People are hesitant to use their cards online in Pakistan for two main reasons: firstly, they do not find paying digitally as convenient – refunds with cards can take several weeks. We introduced the Daraz Wallet to make refunds instantaneous and solve this issue. And secondly, people still prefer to see the product before they pay for it despite that we offer Purchase Protection on all orders,” said Saya.

Here is a measure of just how few customers use the return policies: in 2019 – the latest year for which Profit was able to obtain financial data – refunds amounted to just 1.6% of total revenues for that year. That low number is likely driven by a lack of awareness about the refund policy, difficulty or delays in getting refunds processed by both Daraz and the banks, and one other factor that nobody seems willing to say out loud: maybe fraud is not a bigger problem in Pakistan than in any other country.

According to ACI Worldwide, a payments software company, globally, as of April 2020, e-commerce companies face fraud rates equal to approximately 4.3% of revenue. Fraud, in other words, happens everywhere, but in Pakistan, consumers tend to panic about it and then engage in behaviour that shifts the onus of fraud prevention onto themselves rather than the e-commerce company. They do this by relying heavily on cash-on-delivery, which in turn creates a significant bottleneck for the growth of e-commerce in Pakistan.

Can e-commerce grow past cash-on-delivery?

“The fact that cash-on-delivery is still the preferred mode in Pakistan for ‘online shopping’ just exemplifies we majorly lag behind in everything technology, and economy,” said Ammar Habib Khan, an economic analyst at Karandaaz, a venture capital firm, on Twitter.

The problems with cash on delivery are well-documented, but deserve a recap. Briefly, there are four major issues: customer returns and cancellations are much higher, cash cycles are much longer, delivery costs are much more expensive, and the customer experience is worse.

In terms of returns, according to Ravda, cash-on-delivery customers have return and rejection rates as high as 30% at some Pakistani e-commerce companies, compared to just a 7-10% rate for customers who pay by credit or debit card.

And while the e-commerce company receives the cash immediately for card-based transactions, the logistics companies can hold the cash-on-delivery revenue for several weeks, even months, at a time, which creates a significant cash-flow problem.

Delivery costs can be as much as three to four times higher for cash-on-delivery compared to card payments, and that higher cost actually mean that even accounting for the fees that sellers have to pay credit and debit card issuers and other electronic money providers like EasyPaisa, it is more profitable for e-commerce companies to sell via credit and debit cards than by cash-on-delivery.

And of course, cash-on-delivery also requires the person who made the purchase to be home when the delivery comes, which creates a significant coordination issue that results in a massive headache for most people.

All of these issues mean that the e-commerce experience in Pakistan is extremely painful, and most people associate memories of significant annoyances with a transaction conducted online. That, in turn, increases the appeal of going to a physical store, which then slows down the growth of e-commerce in the country.

In short, e-commerce cannot possibly grow on the back of cash-on-delivery. It needs the trust issue to be resolved, which will then also result in the payments issue to be resolved. Going back to what we said earlier: an individual e-commerce business can win big against other e-commerce businesses while relying on cash-on-delivery, but the industry e-commerce will not win against brick-and-mortar retail without electronic payments.

Whoever can solve the payments pain point – which is really a product of the trust issue – will win the race and create a natural monopoly in e-commerce that will be very difficult to beat. Can Daraz become that company? The early data suggests yes, but it will have to invest heavily in the right strategy if it is going to be that company because it faces more competition than meets the eye.

One caveat: part of the challenge is out of the industry’s hands because of the low financial services penetration rates in Pakistan. “Generally, the number of banked people in Pakistan is significantly lesser than other more developed countries,” said Saya. “About 1% of Pakistanis have credit cards – and this includes individuals with multiple cards.”

The future of Pakistani e-commerce and Daraz

As stated above, a key factor in building a successful e-commerce business with be overcoming the trust barrier and getting more people comfortable with the idea of parting with their money before they have the product in their hands. Daraz’s Wallet and Purchase Protection programs are designed to help give customers that confidence, though they appear to be less well-advertised, perhaps because the company fears that they will be gamed by unscrupulous people.

Then there is the fact that Daraz’s parent company – Alibaba – owns one of the largest fintech companies in the world, Ant Financial, which in turn owns a controlling stake in Telenor Microfinance Bank, in which it bought a 45% share for $185 million in March 2018. The Ant involvement likely helped Daraz boost the development of Daraz Wallet, which would allow people to get more comfortable with buying stuff online.

An integrated payments system is often seen as a way to solve the challenge. It explains why Souq – the now-Amazon-owned e-commerce marketplace in the Middle East – owns its own payments platform as well. And why Jumia – Rocket Internet’s e-commerce marketplace for sub-Saharan Africa – also owned its own payments company until relatively recently.

But this is by no means the only strategy. Indeed, one other strategy would be for tech companies that sell entirely different services to enter the e-commerce marketplace and leverage the trust they have built in other areas towards getting people to buy and sell goods online.

Indeed, the single biggest company that sells services online in Pakistan is actually Careem, which has gross billings to customers that are more than twice those of Daraz’s gross merchandise value (more details on Careem’s financials will be the subject of next week’s cover story). And Careem is actively developing its own payment platform as well in addition to its existing prowess over logistics.

It is unclear if Careem can successfully enter the kind of e-commerce space that Daraz occupies, or even if it wants to, but the fact that it has such a large market of people who are willing to transact with it online suggests that there are more ways to solve the trust factor than the ones that Daraz is trying.

For its part, Daraz is not sitting idly by on its lead. It continues to invest heavily in maintaining its market position.

“We’ve invested $50 million to date and, to be honest, $50 million is a lot of money of course but in the grand scheme of things, what it cost to build an e-commerce marketplace when compared to other markets it could easily go into billions,” said Mikkelsen. “We want to do it much more efficiently. We’ve allocated more than $100 million for Pakistan over the next three years for logistics infrastructure, localised tech solutions, expanding Daraz University, and upgrading the customer experience.”

That war chest – backed as it is by Alibaba’s resources – is likely to be quite intimidating to any prospective competitors. And Daraz remains as aggressive as ever in its ambitions to grow in the Pakistani market. In a pre-pandemic internal projection – obtained by Profit – the company’s management had projected hitting $1 billion in gross merchandise value by 2023.

The company is a little more circumspect about that goal now, but is still aiming high. “A $1 billion GMV for 2023 will be challenging but not impossible. Our focus in the coming years is first and foremost building a healthy marketplace business and great customer/seller experience,” said Saya.

That focus is likely the right one: because Daraz is not just competing against all of those e-commerce companies on Facebook and Instagram. It is also competing against every physical retail store in the country. It is a daunting market to take on, and one that will take monumental effort to maintain a lead in.

The competition for the crown of e-commerce royalty in Pakistan is by no means over.