Zia Chishti had it coming. That much has become apparent after the harrowing testimony of Tatiana Spottiswoode, a former Afiniti employee, who has accused the Pakistani-American entrepreneur of sexually assaulting her.

The details that have come out as a result of Ms Spottiswoode’s testimony have been graphic and intolerable. The abuses committed against her are vile. But why is this any of our business?

The incident took place years ago, and it has only come to light as part of a congressional investigation on the culture of forced arbitration for victims of sexual abuse in the workplace. It is a thoroughly American problem, with an American at the center.

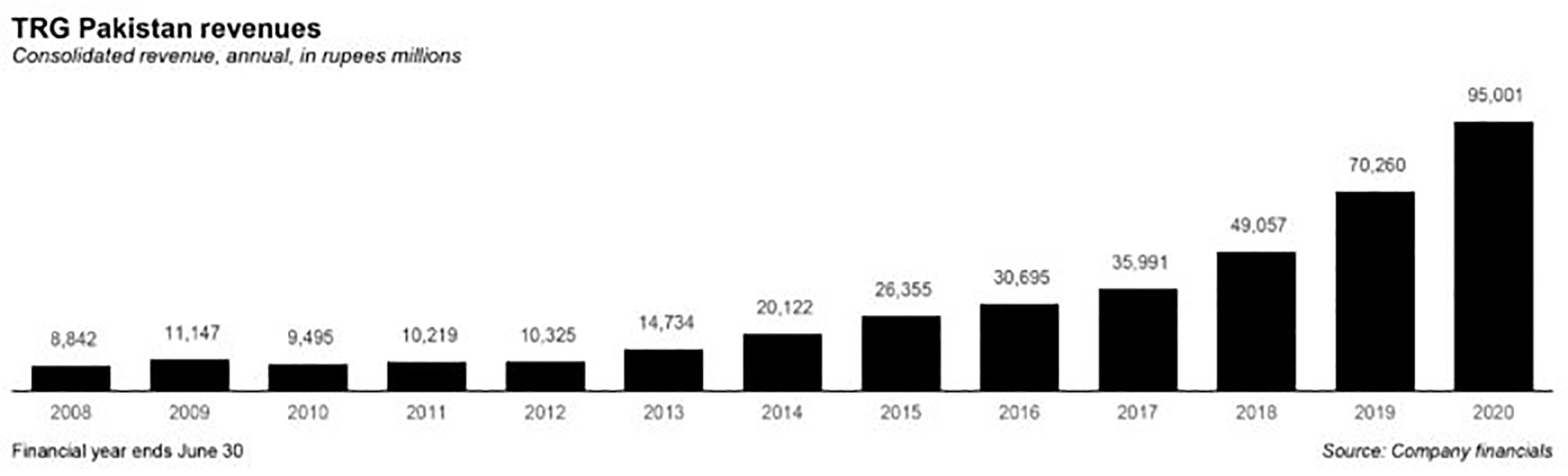

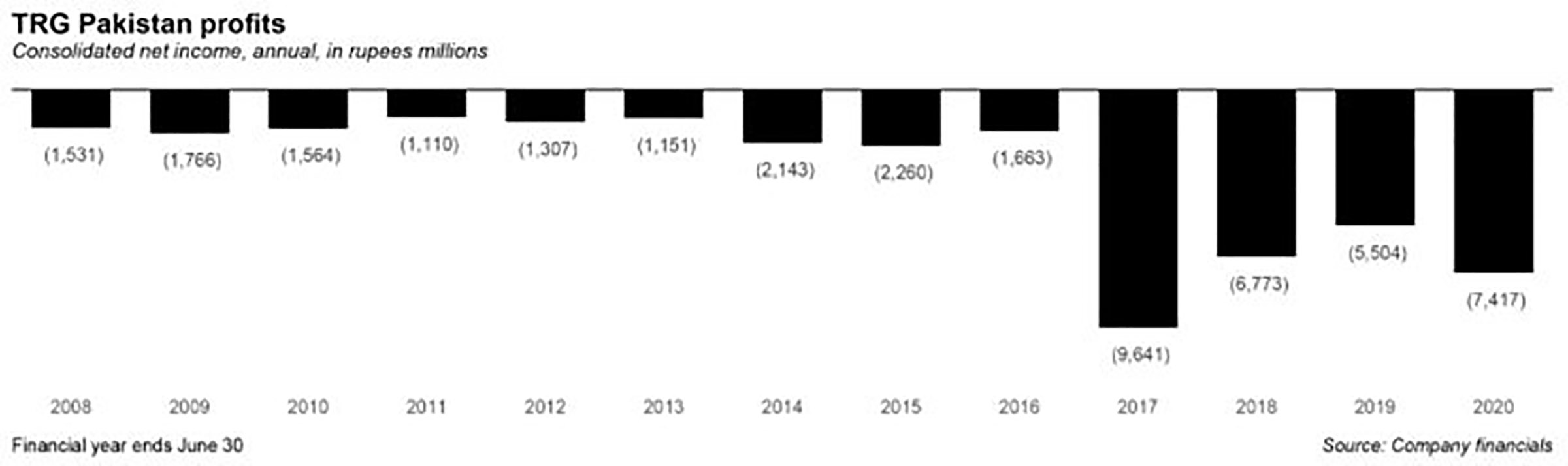

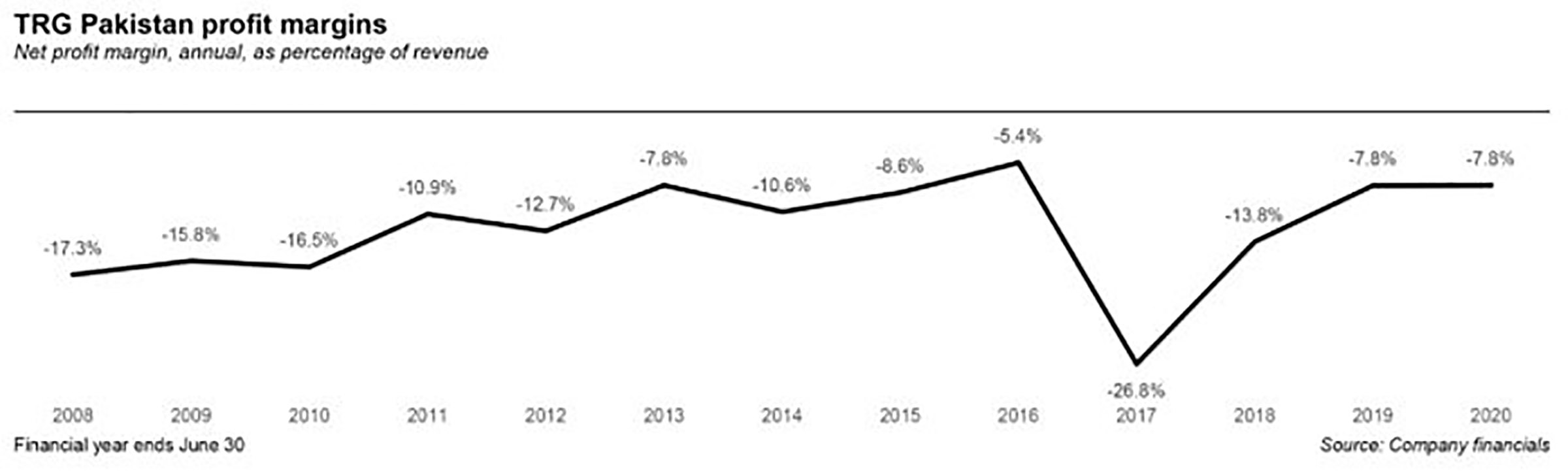

But the fallout from Chishti’s outing has had a corresponding effect on Pakistan. The share prices of TRG Pakistan, a holding company of which Chishti is the CEO, fell from Rs 130 to Rs 111 in a single day as the company faced the charge from panic sellers. According to Topline Securities, TRG Pakistan Ltd alone dragged the benchmark index down by 101.51 points.

And the effect on the stock market is perhaps the most insignificant and short-term impact that the whole affair has had on Pakistan. In response to the allegations surfacing, the general response from the finance community of the country has either been silence, or a complete denial of Ms Spottiswoode’s accusations. The claim has been that the testimony was part of some ‘conspiracy’ to put down a major player in the American tech space because he was a Pakistani. And these views have not just come out from the rumour mill. They have also been expressed by senior professionals.

The truth is that Chishti has turned out to be a vile man that has been accused of egregious, violent, criminal behaviour and is now facing the music. What is Pakistan’s role in all of this? Nothing. There is, of course, the impact on the stock market and this article will discuss that near the end. But the main outcome of the entire event has been that there are truths being revealed about Pakistan’s finance community, most of all that in the age of the MeToo movement corporate Pakistan is vastly unprepared to deal with such fallout, and there are plenty of lessons to be learned.

What happened

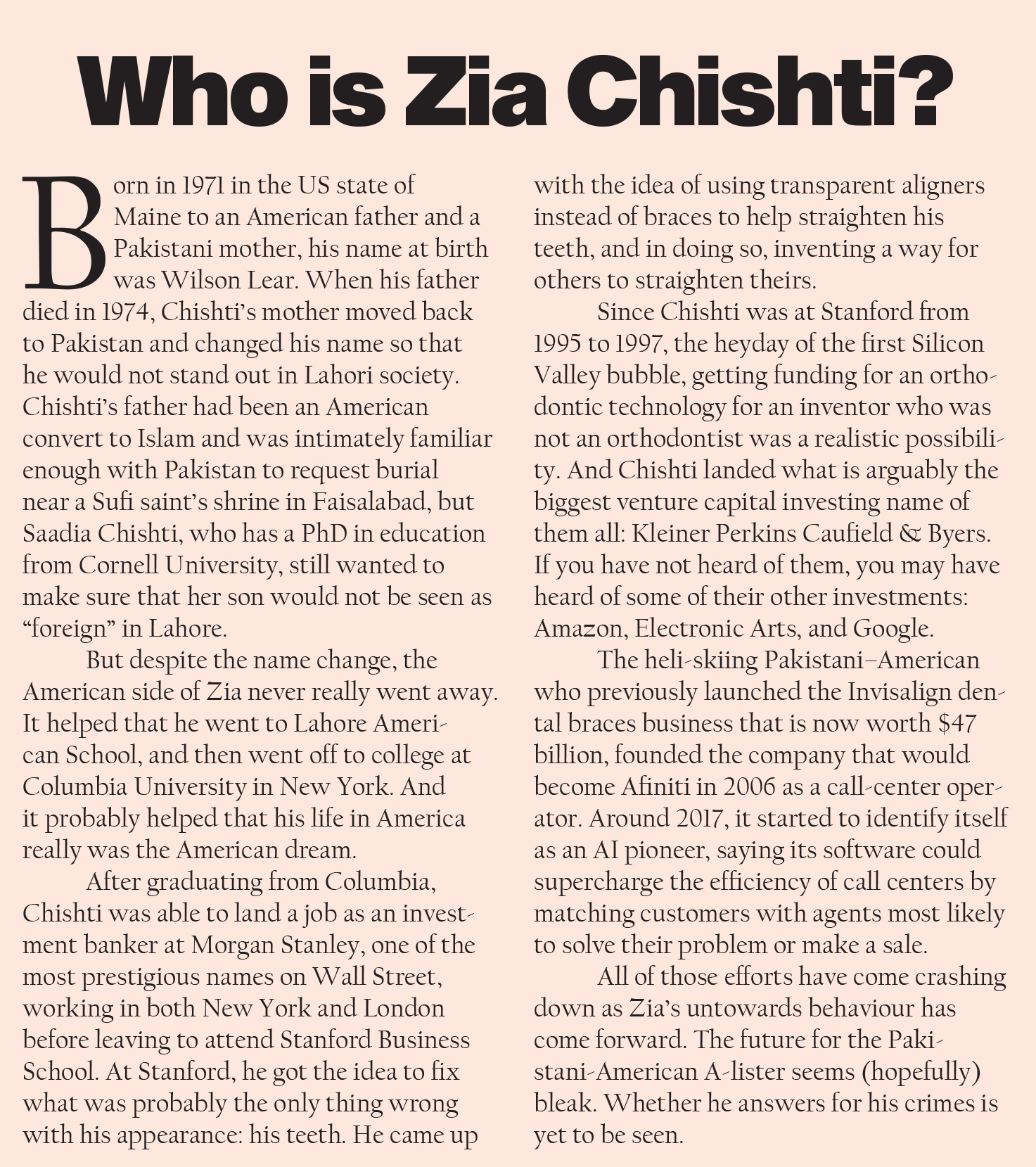

Chishti has been profiled in the past by this magazine. In 2017, a story about his life and work appeared in Profit precisely because his story is undoubtedly a compelling one. Everything you need to know about Chishti’s early life and his rise is in there. All you need to know for now is that he was now on his second heavyweight company and on his way up to being an A-lister.

Founded in 2006 as a call-center operator, Afiniti started to identify itself as an AI pioneer, saying its software could supercharge the efficiency of call centers by matching customers with agents most likely to solve their problem or make a sale around 2017. On the back of this pitch and at a time when technology companies were getting the lion’s share of new investment, it seemed nothing could stop Afiniti.

On Friday, Chishti was ousted unceremoniously from his position as CEO of Afiniti, marking an uncertain and tumultuous moment in the company’s history. Pakistan’s involvement in this entire affair stems from the fact that Afiniti is partly owned by TRG (The Resource Group) Pakistan, which was created in 2002 specifically to act as the global holding company for all of TRG’s investments. It was listed on the then Karachi Stock Exchange in July 2003. TRG was the original company that Chishti had founded out of which Afiniti had grown.

The ownership structure of TRG is highly complex and consists of several layers of holding companies. TRG Pakistan is the overall holding company, but it does not own the entirety of TRG International, which in turn does not necessarily own the entirety of the shares in its portfolio companies. At each stage, there are minority investors who own significant stakes, which makes it difficult to track exactly how much the overall portfolio is worth, and how much of it is owned by the shareholders of the publicly listed company on the Pakistan Stock Exchange.

For most of its existence, TRG Pakistan’s subsidiary was TRG International, which is a British Virgin Islands-incorporated holding company that in turn owns stakes in most of TRG’s portfolio companies. However, in June 2020, TRG Pakistan’s share in TRG International changed from 57.16% to 46.03%. It is no longer a subsidiary, but is instead, technically, an affiliated company.

While Chishti’s removal as the CEO of Afiniti has been announced, no word has been heard about his position as CEO of TRG Pakistan. The grapevine is indicating that Chishti is as well as gone from TRG Pakistan as well, but an official statement is still awaited.

The problem in Pakistan

This is where our conversation about attitudes in Pakistan begins. Almost immediately after videos of the testimony surfaced, the reaction from Pakistani quarters was to raise ifs and buts. One prominent CEO that has sway in the stock market tweeted saying “I met Zia Chishti in 2003 while approving TRG IPO prospectus at SECP. He was full of ideas and wanted to grow the company at an international scale which he did successfully. I was saddened to see the news this morning. We don’t know the whole truth but it is irrelevant now.” Another senior professional of Pakistan’s finance circles, an investment banker, took it one step further saying “Every time a Pakistani tries to strike it big on the global stage, he will be brought down. History is replete with such examples.”

*** Editor’s note at the end of this article.

This kind of attitude is exactly what is wrong with corporations not just in Pakistan but all over the world. The immediate reaction to powerful men being outed as harassers and abusers is suspicion. Suspicion, not of those facing the fire, but of the accusers that gather up the courage to actually come out and name the people that caused them harm. All of this is despite the fact that for a survivor of abuse to come forward and name the person responsible requires going through legal and bureaucratic hell, especially when it comes to this kind of behaviour in the workplace.

And workplace sexual harassment is a very serious and pervasive problem in Pakistani society. In a special report by Dawn in 2018, it was reported that in a survey of 300 working women in Pakistan, abuse and discrimination in Pakistan’s workplaces, including universities, are pervasive, mostly unreported and ignored by senior managers. The report stated that in response to being asked whether women were made to stay silent about workplace harassment, 61 per cent said their employers did not coerce them to keep quiet, but a significant 35pc were told to remain silent by their colleagues and bosses. That is a massive percentage.

When it comes to formal reporting mechanisms, testimonies from women suggest most lack faith in the process — only 17pc of those who experienced harassment approached their organisation’s internal inquiry committees. Despite 59pc reporting that their management does take harassment seriously, most women expressed worry that managers wouldn’t sanction harassers and their work situations would not improve. Most women felt they would not be believed during investigations or when perpetrators had support in high places. Essentially, these harassers are taken seriously enough to get a reprimand and a slap on the wrist.

Pakistan is clearly far behind in this regard, and the attitudes towards the outing of Zia Chisti has shown that more than ever. Even in the current case, Ms Spottiswoode has not come forward as part of an investigation of the culture at Afiniti, but as part of a congressional investigation on workplaces that add forced arbitration clauses to the contracts of their employees. This means that if senior management does something untowards, a person cannot take them to court because their contract means they have to go to the arbitration table no matter what. At the table, these large companies manage to use their A-list lawyers to bully and strong-arm people into taking settlements and signing non-disclosure agreements.

In Pakistan, there is nothing so sophisticated. Companies do not add forced arbitration clauses because they know even if accusations came to light, they would either not be taken seriously or languish in the court system forever. In the process, the woman filing the complaint would end up also in a heap of social and legal trouble. Perhaps the most significant case in Pakistan where this was on display was that of Patari.

Unlike Afiniti, Patari was a company that was doomed to fail from the first day because it was a bad business model. When allegations against their founder and CEO came to the surface, initially the company made it seem like he would be stepping aside. When it came forward that he was still very much running the show just from behind the curtain, senior management of the company stepped down in opposition. However, nothing became of the matter and it turned into a situation where the CEO, Khalid Mubashir Bajwa, continues to play a role in the operations of Patari.

These matters are always quite complicated. In the case of Chishti, it must be remembered that while the board might have ousted him as the CEO of Afiniti, he is still one of the largest shareholders both in this company, and the company’s parent and holding companies. This means that Chishti, even if he goes to prison, will have a huge chunk of Afiniti and might even be able to throw his weight around a little. A company like Afiniti which has solid business fundamentals and funding is bound to continue making profits if it has a product that is valuable on the market. In such a situation, what can companies actually do?

In more developed places where the impact of the MeToo movement has been stark, companies have playbooks that they use for situations like this. They have strategies, they have restructured at times to improve workplace culture and avoid the kind of fallout that Afiniti is now facing because of Chishti. It has become clear that Afiniti did have a serious culture of hard drinking and partying which led to situations like this. But in Pakistan, instead of facing the reality, companies prefer to either ignore the problem, belittle it, or the people accused of such crimes then find legions of supporters that help them poison social media narrative in their favour.

The effect on the stocks

There have been immediate effects of Chishti’s removal in Pakistan. While he has not been removed as CEO of TRG Pakistan, it is a move that according to many experts is just around the corner after his ouster from the Afiniti chair.

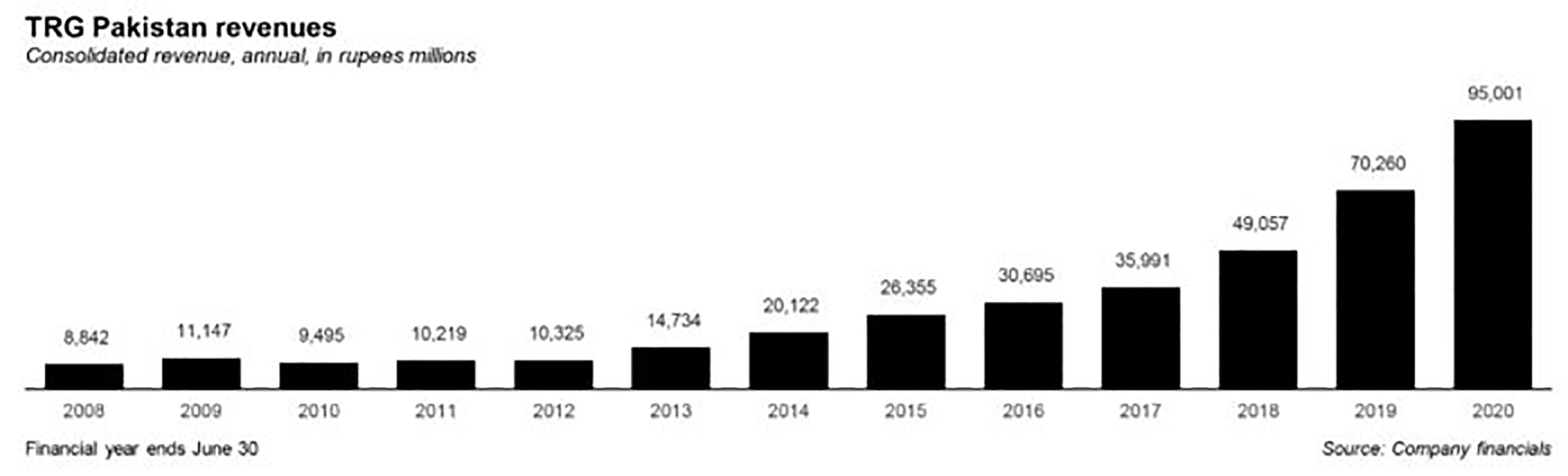

TRG Pakistan stock has long been considered a holy and long game that will always work out. Much of this has been because of the recent pivot of Afiniti and it turning the corner towards becoming a ‘tech’ company. Back in April 2020, TRG’s stock stood at around Rs12. It then climbed to Rs51 in August 2020. Between December 2020, to February 2021, the stock climbed an absurd amount, the current Rs125. Back then there was an expectation, according to market rumours, that it would certainly cross north of Rs150. That is why the current fall has been quite alarming for investors.

The company has this many investors for a few reasons. The first is that it is a tech company which is easy to hype up. Back in February this year, a document with no author has been making the rounds on Whatsapp, which puts the valuation of TRG Pakistan at roughly Rs400. It does so by comparing the various subsidiaries – Afiniti, E-telequote – to their listed peers on American stock exchanges, and arrives at a projected total valuation of TRG Pakistan.

Whether the stock was worth that much or not, it is the fact that people certainly believe it. In interviews conducted by Profit back then all sources interviewed either alluded to the document, or simply quoted the document verbatim as analysis. Some even went so far as to call TRG Pakistan as a non-traditional company trying out something new, that it was revolutionary.

The other reason they gave was that Zia Chisti was ‘charismatic’, that both the JS Group and AKD – traditional rivals- were bullish about TRG. That charisma is not only gone now, it is very much in the dumps and Chishti’s personal role in the company has made the life of investors incredibly difficult.

Despite this, after the initial fall the price of TRG stock has remained relatively stable and it seems it might even climb once the dust settles. People still very much believe in TRG Pakistan and its history of providing profits.

The company claims to have an ‘unbroken track record of over a decade’ in generating positive returns on each investment. That is what they will be banking on right now. What this also tells us once again is that the effect on the stock market is not the story. In fact, the stock prices staying as stable as they did means that not as many investors panic sold as they might. That also points towards the indifference in Pakistan towards allegations such as the one against Chishti. The stock prices will eventually rise, and Chishti may even be removed as CEO of TRG Pakistan, but when will corporate Pakistan catch up to the reality of the times? Not any time soon by the looks of it. The only question is whether there will be a rude awakening that will make them.

{Editor’s note: The names of the persons quoted above have been removed. As part of this article, Profit took a stance on workplace sexual harassment but unfortunately, the conversation has instead been redirected towards the two people whose tweets were quoted as examples of the dismissive attitude we are trying to challenge. On request, Profit has decided to remove the names of the people whose tweets were quoted.

However, there will be no retraction and no apology. We stand by what we had published, and will defend our right to expression of opinion in any criminal or civil litigation over this issue, and strongly reiterate that no journalistic ethics were compromised in publishing this article.}

Hi

Good information

Kindly visit my website i have thousands of free SVG files and free theme, Plugins

freesvg.uk

Zia Chishti is a disgusting pig and should be put in jail for a long time. A sexual predator and fraud who hates women

A 46-country study has shown that India is placed at 39 with the people walking just 4,297 steps a day on an average. While Indonesia enjoys the position of being the world’s laziest country, India is no better

Get the latest NFL football news, scores, stats, standings, fantasy games, and more from ESPN.