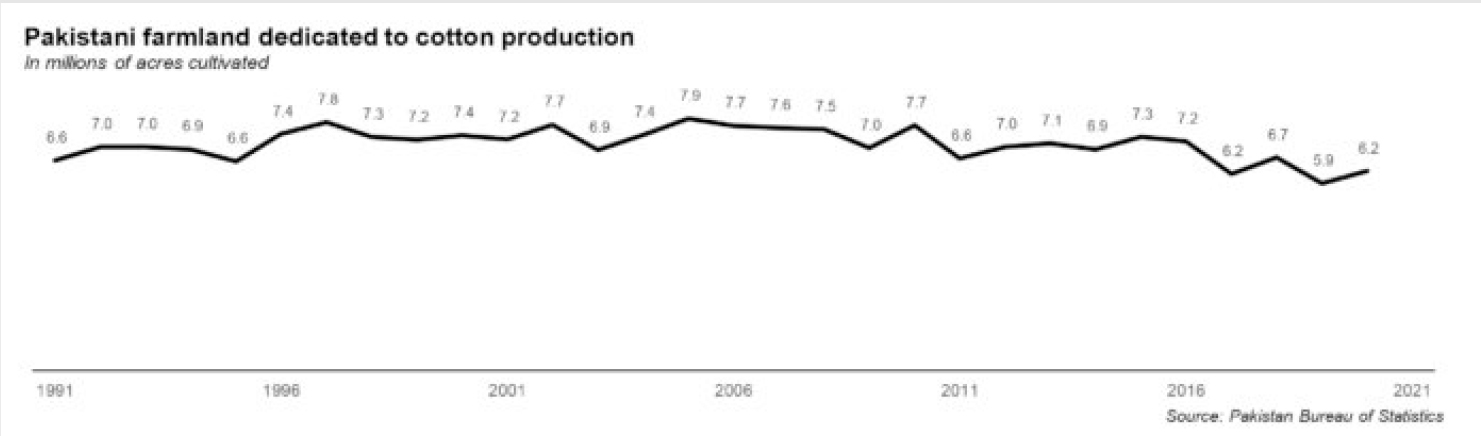

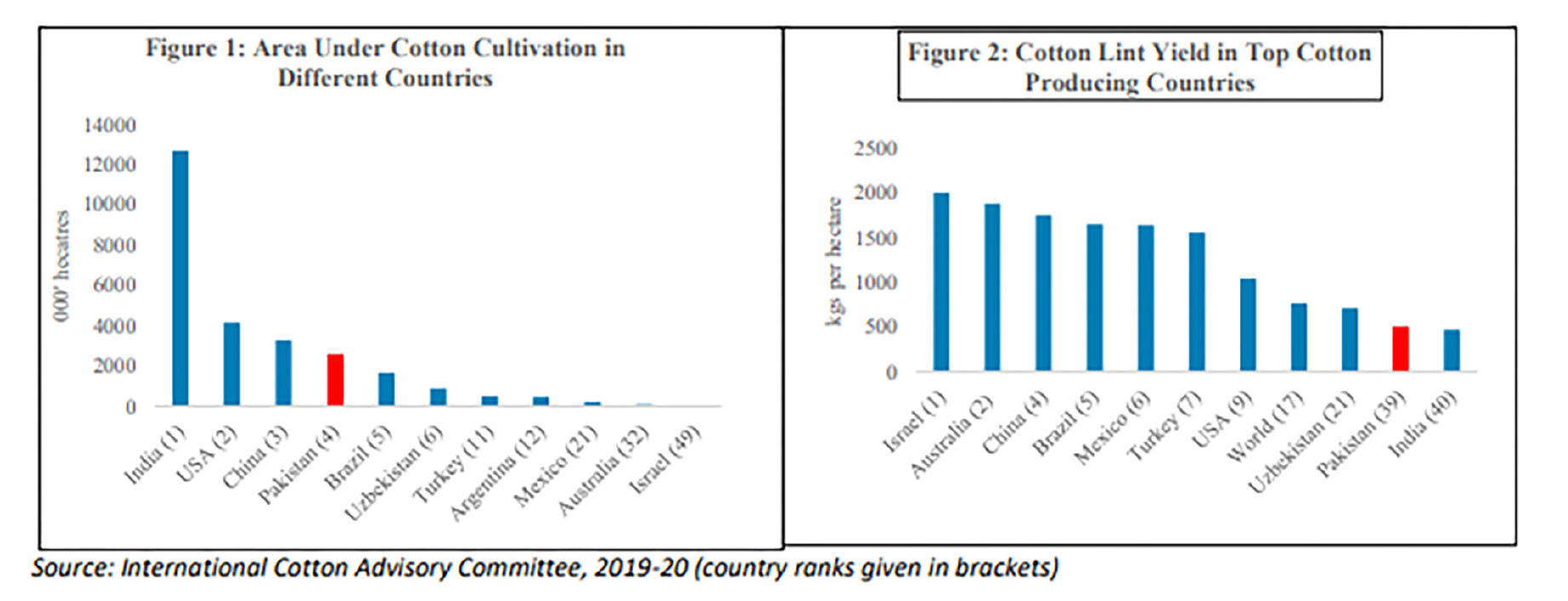

In October 2019, Pakistan’s cotton crop was on the ropes. The story was not a new one. Since at least 2015, cotton yield in the country has seen a downward trend. Between 2015 and 2020, Pakistan’s production of cotton declined by nearly 35%, from nearly 14 million bales in 2015 to just over 9 million bales in 2020.

Farmers over the past decade have abandoned cotton in favour of more profitable crops like sugarcane, and changing climatic conditions have made the cotton seed in Pakistan less resistant and more likely to fail — which means growing it has become a bad business decision for a number of agriculturalists.

This has posed problems. The cotton supply chain is a long and complicated one. It begins very simply from the cotton fields where the cotton plant is grown, harvested, picked, and taken to the large ginning facilities that exist in the country. Here it is ginned and converted into a form that can be used to manufacture clothing and other cotton products.

This is where the secondary market comes into play. In the secondary sector, the cotton-based textile industries have a 21% share in large-scale manufacturing and consequently a 2% share in the national GDP. In the past, these textile manufacturers would depend on local cotton to bolster their production and make their products cheaper. Over time, the textile industry has started relying more and more on expensive imported cotton to meet their needs. For a while now it has been on the cards that Pakistani cotton might be on a very steady route to decline. That is, until, a bit of news this year gave hope to both the textile industry and cotton farmers that there may still be a chance for Pakistan’s cotton crop.

In March 2022, it became apparent that the cotton crop in Pakistan had made gains. According to the Pakistan Cotton Ginners Association, figures from November 2021 showed that cotton outputs had increased by as much as 70%. In the first quarter of 2022, a sudden rise in demand and prices in the world market meant more farmers were growing cotton — and yield per hectare was increasing as well.

The improvement in the fate of the cotton crop has been noticed. The unfortunate part is that it has come on the back of an anomaly of international trade created by the Covid-19 pandemic. The government has done very little to improve the status of the cotton crop. Farmers, too, have been slow in adopting better farming practices that will produce more cotton per hectare. What this slight upward trend from this year does tell us, however, is that the cotton crop has a chance in Pakistan, one that can be seized. But is anyone up to the task?

Setting perimeters – what happened until 2020?

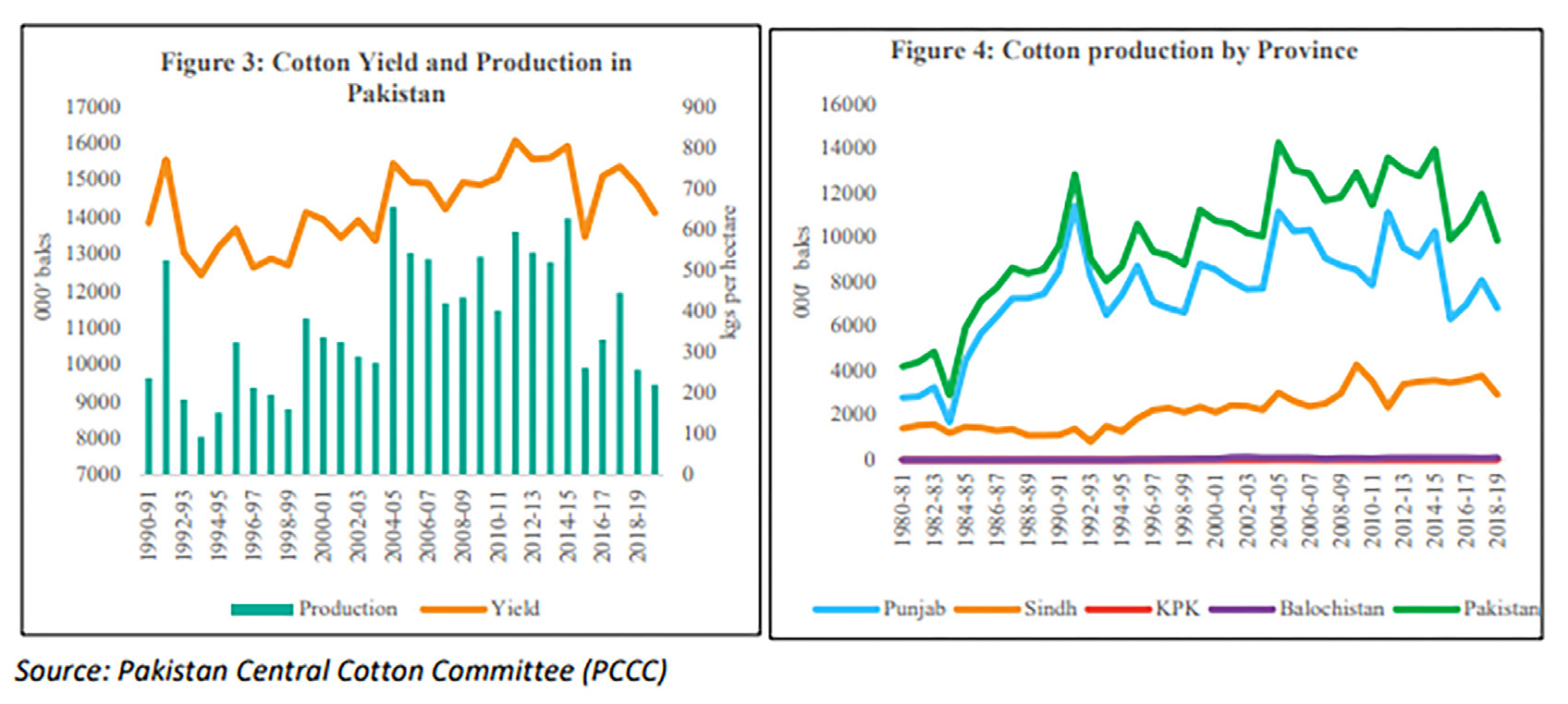

The cotton crop has a certain status in Pakistan. It is not only a plant that is native to Pakistan, but it has had a storied history and has historically been a pillar for the textile industry of the country, which is one of the largest export oriented sectors.

According to a 2021 report of the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), raw cotton consumption grew at an annual growth rate of 7% between 1982 and 2008 to reach 15.6 million bales in 2007-08 in Pakistan. However, between 2007-8 Pakistan was hit by the global recession. The textile industry faced challenges due to high energy costs, rupee depreciation vis-à-vis the US $ and other currencies, and a high cost of doing business. As a result, there was a reduction in the number of textile mills operating in the country from about 450 units in 2009 to 400 units in 2019. This decrease has simultaneously seen the domestic demand for cotton dip in the country.

Farmers and the textile industry up until the 2008 financial crisis had been dependent on each other. Farmers would produce the crop without the fear that demand would fall, and the government did not need to announce a support price either. But when mills started shutting down, suddenly there was more cotton and not enough buyers. After a harsh couple of years, farmers also began going back on cotton and its price fell, resulting in production decreasing.

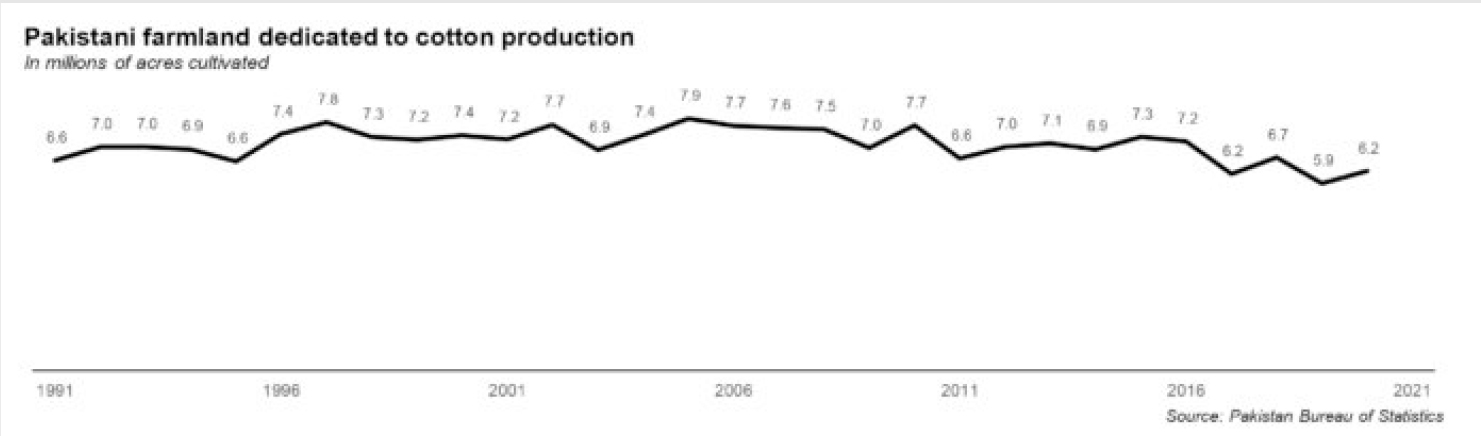

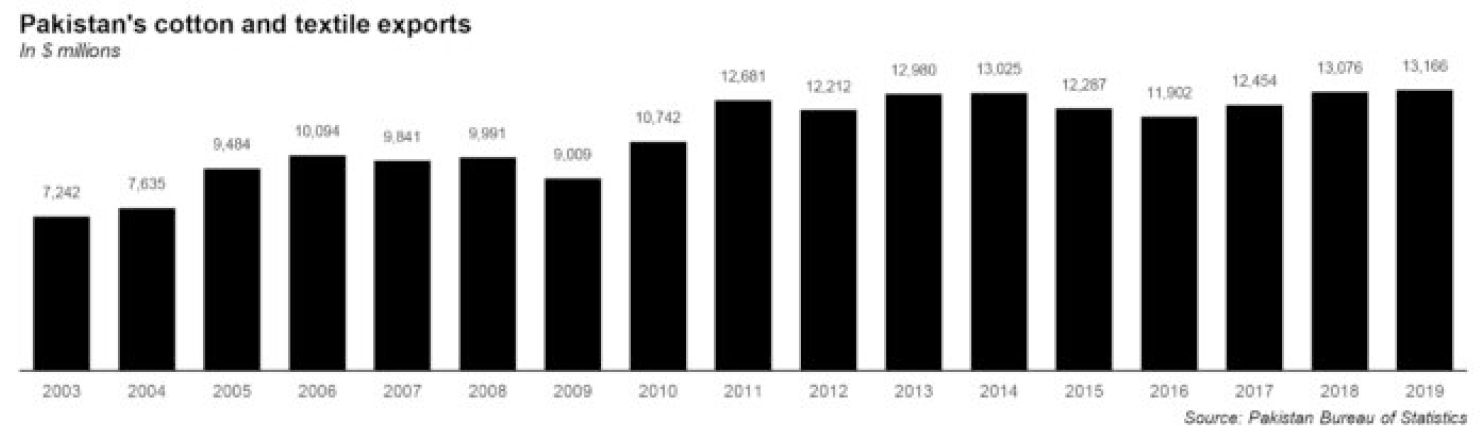

As a result, exports were also affected. At the same time, since farmers were losing interest in cotton, very little cotton research was done in the country. This meant that other cotton producing countries were able to use the latest seed technology and science to increase their yield while Pakistan fell behind. Here is a sobering statistic. Two decades ago, Pakistan’s cotton was in demand globally. However over those 20 years, countries such as Bangladesh, Vietnam and Cambodia have all used better growing techniques to get ahead of Pakistan. In 2003, when Pakistan’s textile exports were $8.3 billion, Vietnam’s textile exports were $3.87 billion, Bangladesh’s were at $5.5 billion. Now Vietnam is at $36.68 billion and Bangladesh is at $40.96 billion, while Pakistan is struggling to hit $25.3 billion in 2020.

The explanations behind this are multiple. Pakistan needs to increase not just the amount of cotton it produces, but also improve the quality of the cotton crop. Currently, Pakistani cotton is considered second grade, and if the crop quality is improved there would be greater demand at a greater price. More importantly, by improving the crop, the entire textile industry will benefit since the quality of all products will improve at source.

Pakistan has been missing its export targets since last year. In 2019, the production target for cotton had been 15 million cotton bales, and only 10.2 million bales were produced. Bad weather at the end of the year meant that there were only 8 million bales at the end. The reason behind this, again, is that the government places very little emphasis on how the cotton is grown. Factors like climate change, lack of proper research by local research institutes, and no cotton policy, and the loss of cotton production areas to other cash crops have all played a role in this, which is why it is so important to focus on techniques to grow more and better quality cotton.

About those targets

There is, of course, an issue with these targets themselves. Of all the bad habits the government of Pakistan has, perhaps, one of the worst is the one picked up by the Ayub Administration in 1958 from the Soviet Union of building a government that assumes that it operates in a planned economy, even as it presides over at least a semi-open market economy. The habit is of introducing ‘targets’ for the economy.

Every year, the government of Pakistan has announced an absurdly high cotton production ‘target’. This year, same as always, it will be seen to ‘miss’ its target, as the government of Pakistan does not own any cotton farms, most of the banks do not lend to farmers anyway, and there are no companies that supply farmers with what they need.

The government of Pakistan is not a direct participant in the cotton supply chain at all, and implements no policies designed to benefit cotton farmers or the cultivation of cotton more broadly, and yet somehow, the bureaucrats in Islamabad think that setting a target is enough for them to help the country achieve higher production numbers. And the targets themselves are absurd: Over the past 30 years, only twice has Pakistan’s cotton production crossed 14 million bales, and yet somehow the government sets the target of 15 million bales of cotton the year after the country barely managed to scrape by with producing 9 million bales.

Missing those targets is not the problem. No. The targets defy all reason and are not meant to be reached in the first place as it would be impossible. Even though Pakistan has low yields, the real surprise has been the fact that output this year is somewhat better, despite higher than usual rainfalls, gusty winds in certain regions, and pest attacks on standing crops.

Why was cotton ‘in’ this year?

These problems in Pakistan’s cotton industry have been persistent for more than a decade now. We have discussed poor seeds, poor planning, bad target setting, and better crop options for farmers. This year, however, something happened that made cotton popular again — the impacts of Covid19 trickling through.

You see, cotton has been on the decline since 2008, as we have seen. As mentioned earlier in the story, between 2015 and 2020, Pakistan’s production of cotton declined. This led to the textile industry claiming that they would thrive on imported cotton instead of depending on local cotton. This worked out especially since the cotton Pakistan produced was second grade.

But when the pandemic hit, everything changed and the local industry found that importing cotton was no longer an option. International cotton prices (in rupee terms) during the last year have gone up by almost 30% — from PKR 12,606 on July 1, 2021, to PKR 18,259 by mid-February this year. The ever-dwindling value of the rupee not only doubled the impact of import for Pakistani millers but also made it next to impossible to calculate the final cost of production, rendering import commercially non-feasible for the industry.

On top of this, there were shipping concerns. A report in Dawn from March 2022 chronicled how it takes more than 120 days to ship cotton to Pakistan these days, against the 30-day hiatus in pre-Covid times. These circumstances deflated the textile industry’s claim that it could thrive, even survive, on imported cotton and forced it to value local crops, thus setting the stage for the cotton revival in the country.

“‘In the first year-and-a-half (of Covid), all major world brands had their stocks exhausted as cotton supplies got squeezed quickly but demand died slowly — stripping the brands naked of their product,’ Kamran Arshad, owner of the Ghazi Fabrics, explains the demand side. With different governments incentivising their industry and compensating their people, the demand for textile products started coming back but, by that time, shipping lines had stopped and industry was closed. As the world textile industry started reviving, demand became too overwhelming for it to meet.”

Since the impact of Covid was comparatively milder on Pakistan, its industry started almost eight months ahead of the rest of the world and so the entire capacity was booked within weeks. This sent the industry in a mad chase for cotton, hence improving local prices, explains Arshad.

A big part, simultaneously, was that just a year before, Pakistan had started to focus on improved cotton production methods. This is what allowed it to cover the gap for the industry when importing cotton was no longer feasible, the Dawn report adds. “In 2021, acreage fell by 17% in Punjab — from 3.8 million acres in 2020 to 3.1m last year — but production fell by only 2%.”

This means that average yield increased over time. The report quotes Dr Saghir Ahmad, director of the Central Cotton Research Institute (Multan), as saying, “the average yield jumped from 15.68 maunds in 2020 to 19.62 maunds per acre in Punjab in 2021. In Sindh, it was even better; 30 maunds per acre, pushing the national average to 25 maunds per acre. This better production, along with a massive rise in world prices, has now set the stage for acreage expansion this year.”

What does it mean

The textile industry has stayed largely unimpressed with this. They have chalked the increase up to special circumstances, and are still relying on imports. According to them, local cotton does have the potential to cover local demand but unless solid steps are taken there will be no point to it. “This has not been a remarkable increase,” says Raza Baqir, the secretary general of the All Pakistan Textile Mills Association (APTMA).

“There has been a marked increase in per hectare yield in some areas which is very encouraging, however, in some areas decreasing yields have also been observed, and overall the scale has barely been budged. We still need to import nearly half of our quantity from abroad, which with rising prices is difficult. We have observed a consistent improvement since at least 2019, but overall it has to be said it was all very marginal.”

The key here is the minor improvement that has been seen over the past three years. Before this, for nearly a decade, Pakistan’s cotton crop suffered from multiple ailments. The narrow genetic base of cotton germplasm which are prone to insect and disease, along with reliance of Pakistan on a back-crossed 17 year old biotechnology have resulted in low yield per area. Lack of quality and advanced gene technology is a serious issue that has plagued cotton productivity in Pakistan. The attack of pests such as the locust attacks in the past couple of years and other consequences of climate change have all caused issues.

This year, however, a peculiarity of the international supply chain made a case for Pakistani cottons. Just as the problems of this crop have been listed, its solutions are also readily available. Investment is required in cotton research. More importantly, this year the price of cotton was well above the support price of PKR 5000 per bale (40KG) but the early announcement of this support price gave farmers the confidence to pursue this crop. With all of these considerations, Pakistan can once again go back to its cotton glory days, and perhaps bolster its textile industry and exports along the way.

A cotton bales isn’t 40kg

Standard cotton bale is 170kg

I have perused every one of your posts and all are exceptionally enlightening. Gratitude for sharing and keep it up like this.

사설 카지노

j9korea.com