We start in the heart of Lahore’s Model Town. The area’s famous circular bank-square market is a peculiar sight these days. Dead in the centre of the pre-partition co-op, the market has been known over the years for its cheap food and communal sitting area.

It is a sort of glorified food court really. There is a circular brick platform in the middle with lots of plastic chairs and tables. The little sitting area is surrounded by shops, stalls, and kiosks selling all manner of food cheap and pricey. The market has been around for decades. Before there was H Block market in DHA or G1 Market in Johar Town or Karim Block there was Bank Square Market. It has served, in particular, as a haunt for young students looking for cheap food and spaces to loiter.

And of course where there are young people loitering there is tobacco. And for years that has indeed been the case. Little khokhas and corner shops have long been the widespread distribution arm of Big Tobacco. Even in 2023 small grocers are the largest distribution channel for cigarettes in Pakistan in retail volume terms.

But the little round Bank Square Market today tells a story of changing times. Within this market that has a radius barely over 200 metres there are a grand total of seven shops that sell vapes. The shops are renting out prime real estate. They specialise in selling just vapes — that means they don’t keep cigarettes with them. And Bank Square isn’t the only place where this phenomenon has been observed. All over Lahore and indeed all over Pakistan the dedicated stores selling vapes have become common over the past few years. While vapes and e-cigarettes have been around in the country for longer, they have become far more easily accessible since around 2019-20 when a number of retailers began importing vaping devices, flavours, and in large quantities from China and Thailand to grow their retail footprint.

The threat from the growing trend of vaping has not gone unnoticed. Pakistan’s tobacco industry has been watching closely as these imported products gain more traction. Not only are people now getting their nicotine fix elsewhere, but a lot more people that would otherwise have started smoking have instead chosen to start vaping instead. According to one report that has been used by the tobacco industry for information, in the five years from 2017 to 2022 the number of people that vaped in Pakistan grew by four times.

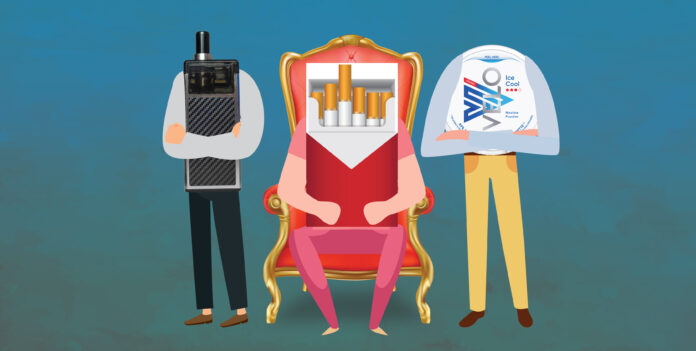

In response Big Tobacco in Pakistan has decided to introduce its own non-tobacco nicotine products. Pakistan Tobacco Company (PTC) has introduced the VUSE vaping systems that are manufactured and distributed by its parent company, British American Tobacco (BAT), to Pakistan. And they have brought it to the market with a big marketing and customer acquisition splash. In response, Philip Morris International (PMI) has also introduced their “heated tobacco” line called IQOS, although they have done so in a decidedly more subtle fashion. At the same time, PTC has also hit the market with their nicotine pouches under the brand name Velo, after which PMI has come up with a near identical product under the brand name Zyn.

As the competition heats up for the nicotine market that exists outside of traditional cigarettes in Pakistan, the question is, who will come out on top? And will these new products ever really replace the Big Kahuna that is the cigarette?

Tobacco Kingdom

Let’s get this out of the way. Cigarettes are bad for you. They are nasty, brutish, disgusting things that poison and cripple some of the best amongst us. They are a filthy, deadly, dangerous, plague upon humanity that have killed more people in the 20th century alone than both world wars combined. Governments across the world have tried (and failed) to wrangle this industry.

As a result, cigarettes are still the Big Kahuna in Pakistan. In 2022 alone, which is the year for which we have the latest available data, a whopping 60 billion cigarette sticks were sold in Pakistan equating to around three billion packs. This is enough cigarettes for every single man, woman, and child to puff away around a cigarette a month in the country. But with only about 13.4% of the population identifying as smokers in Pakistan, it comes out to an average of around 2000 cigarettes per smoker a year.

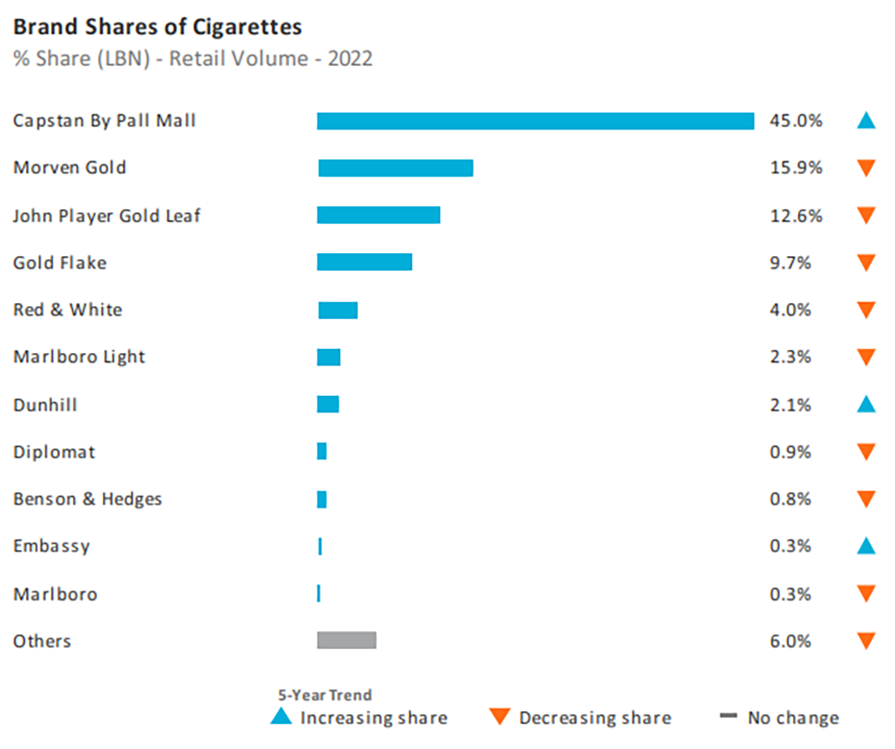

That is, in fact, a modest number. The average smoker globally consumes upwards of 5000 cigarettes a year. But all of the sticks add up, and the cigarette market in Pakistan did retail sales worth nearly Rs 454.4 billion in 2023. These sales are by and far dominated by two companies in Pakistan. There is the Pakistan Tobacco Company Limited (PAKL), which is the Pakistani subsidiary of British American Tobacco. The other company is Philip Morris Pakistan Ltd (PMPK).

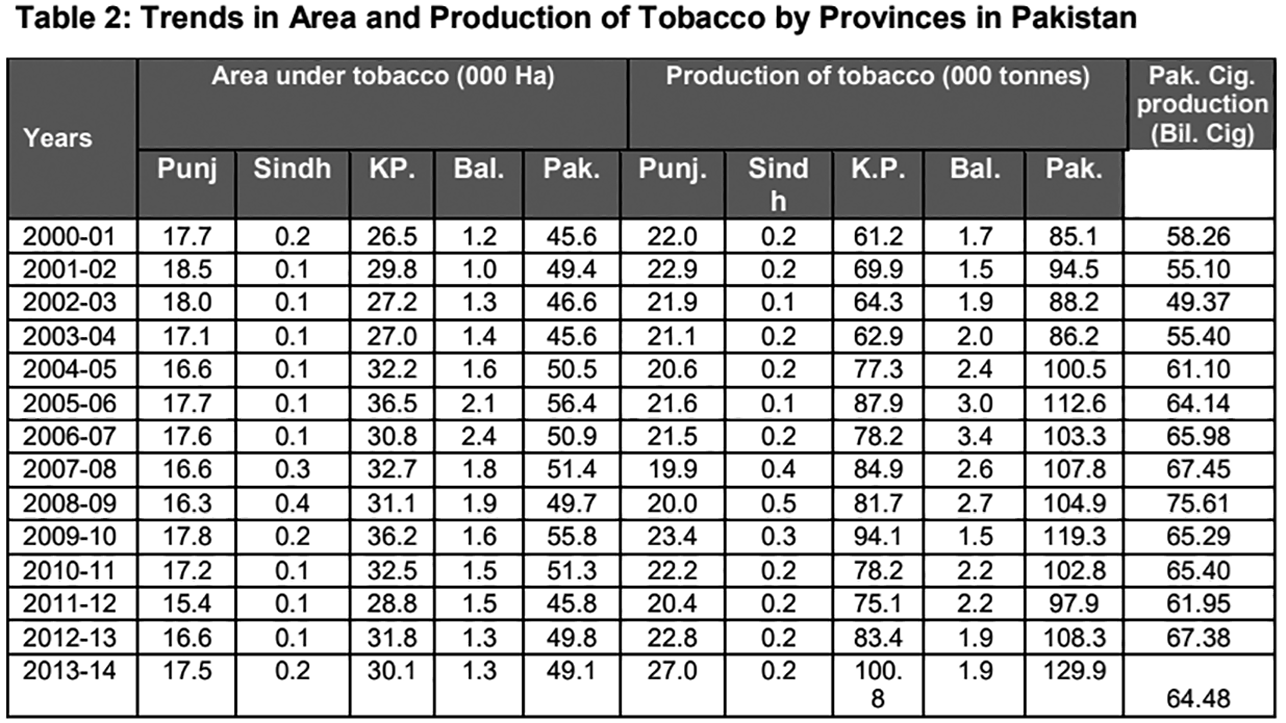

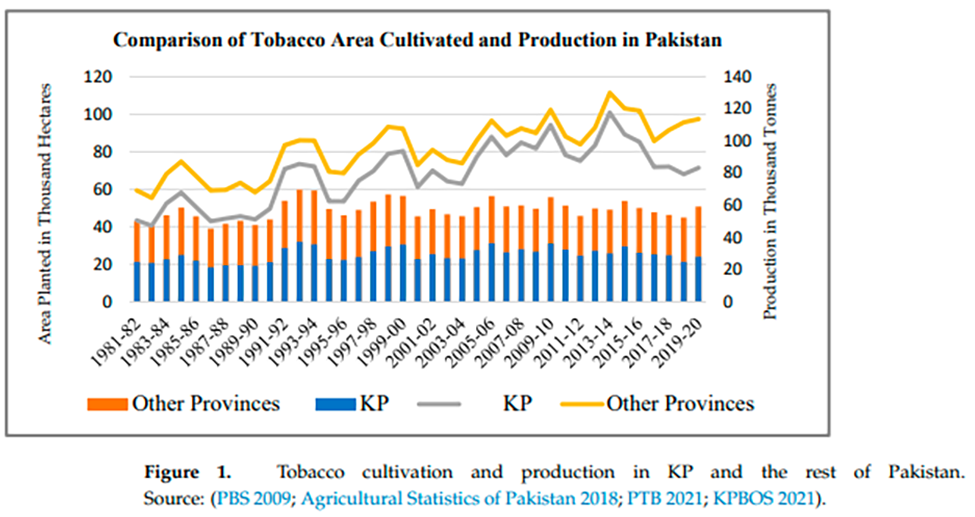

Together these two companies control around 95% of this massive market. The bigger player among the two is PTC, which up until last year held about 70% of the market share compared to Philip Morris which controls just under a quarter of it. Both of these companies manufacture locally and depend on the vast tobacco fields of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. The trajectory of tobacco farming in Pakistan has actually been quite interesting. At the time of partition in 1947 there were plenty of smokers in Pakistan but no tobacco was grown here. Big Tobacco saw this for the opportunity it was and encouraged planting tobacco in the erstwhile North West Frontier Province (NWFP). From 1948 onwards some efforts were made to try and grow the crop, beginning with an experimental 20 acre farm. It was very quickly discovered that KP’s land and climate was ideal for growing tobacco, and by 1968 Pakistan was no longer a net-importer of tobacco.

According to a study by the Abdul Wali Khan University in Mardan, the area under tobacco cultivation in Pakistan was 43,134 hectares in 1980–1981 and 50,800 hectares in 2019–2020, indicating that the area under tobacco cultivation expanded over time due to its profitable nature. The same study found that tobacco production in KP increased from 43,408 tonnes in 1980–1981 to 71,410 tonnes in 2019–2020, while the area under cultivation only rose by around 4,000 hectares between that time.

The remaining 5% of the pie is split between around 50 small scale tobacco companies based out of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa set up by tobacco farmers in the province. These smaller players sell their cigarettes cheap, off brand, and often untaxed. It is a point of particular annoyance for PTC and Philip Morris, with both companies spending exuberant amounts of money each year lobbying for these small cigarette manufacturers to be taxed. And while this in itself is a fascinating dumpster fire, what it tells us is very important: the figures we have for how many cigarettes are consumed in Pakistan are not quite accurate. And the actual amount of cigarettes sold here are much higher than the 60 billion sticks we know of.

The Goliath faces mortality

Cigarettes have been around for a very long time. Early in the 16th century beggars in Seville began to pick up discarded cigar butts, shred them, and roll them in scraps of paper (Spanish papeletes) for smoking, thus improvising the first cigarettes. These poor man’s smokes were known as cigarrillos or “little cigars” in Spanish.

From those antiquated origins the cigarette has persevered and it will continue to persevere. As a product the cigarette has gone through many changes and rebrands. It has been at the centre of some of the greatest marketing campaigns in modern advertising history. Despite the many adverse health effects and direct deaths caused by smoking cigarettes nothing seems to have stopped these unassuming little sticks that are both a product and a cultural cornerstone.

But there is definitely a threat. The indicators are similar all around the globe, and some of the most readily available data comes from the United States where cigarette smoking has fallen to an all time low but the use of vapes and e-cigarettes has continued to climb. About 11% of adults told the CDC in 2023 that they were current cigarette smokers. These rates have fallen consistently since the 1960s when it was first widely publicised that smoking cigarettes causes cancer. At the time nearly half of the global population smoked cigarettes. Meanwhile the use of e-cigarettes in the United States has risen from 4% in 2021 to 6%. That is still around half of the total number of cigarette users but the trend is clear.

In Pakistan as well, cigarettes are far ahead of any other competition. The total retail sales for cigarettes this year have been over Rs 450 billion — and that is despite rising prices of cigarettes due the the government imposing additional taxes on smokes on the direction of the International Monetary Fund. In comparison other products that deliver nicotine are small fries. The overall sales from non-cigarette related nicotine products including nicotine pouches, vapes, and heated tobacco (more on what this is later) amount to a mere Rs 54 billion in 2022.

The competition heats up

The point is not that cigarettes are going anywhere, but rather that other methods of consuming nicotine are fast becoming very popular. Nothing is more indicative of this shift than the reaction that PTC and Philip Morris have had to this situation. Remember, up until around 2018-19 vapes and e-cigarettes in Pakistan were imported products that were hard to find.

In around 2019 a number of chain retailers for vapes started popping up. Shops like Vape Mall, VGod, and Artisan Vapour all became very popular very quickly off the back of large scale import of vaping devices. For those unaware there are essentially a few kinds of vapes available in Pakistan. There are vaping devices you can purchase and fill with “flavour” — which is an oily sort of liquid that contains both the flavouring and the nicotine that reaches the consumer. The vape device is charged and when you inhale it heats the flavour and delivers nicotine in the form of vapour to the person taking the hit. Then there are pods, which are a similar concept except instead of a liquid bottle of flavour the device comes with little capsules you can insert and smoke away. And then finally there are disposable vapes. These are devices that last anywhere from a day to a few weeks and are thrown away once they finish.

“Back in 2019 the items being most imported were vaping devices and vape liquid,” says one tobacco industry executive. ”At the time we were already looking at and considering introducing non-cigarette products but then soon after Covid we noticed an influx of disposable vaping devices. These were less expensive than an entire device and not as much of a commitment. As a result, a lot of people tried them out and became regular users. ” Profit was surprised to discover that the tobacco industry was surprisingly hesitant to speak to a business publication. For an industry that is not allowed to market their products but still have marketing departments with budgets higher than most entire newspapers could ever dream of, one would think their officers would want to talk to the media. But neither the communications nor marketing departments of PTC and Philip Morris responded to any of Profit’s requests for interviews or comments. One executive spoke to us as a personal favour but off the record since it was not their relevant department.

According to the information available with Profit, the abundance and easy availability of e-vapour products in the urban centres of Pakistan, includingIslamabad, Karachi, Lahore, Peshawar,and other major cities, supported the growth in awareness and demand.Shenzhen IVPSTechnology remained the leader in retail value sales of open vaping systems through its SMOK brand,ahead of Shenzhen Smoore Technology and Shenzhen Joye Technology with their respective Vaporesso and Joyetech brands.

Since then a number of other Vape brands have also entered the market. The proliferation of vaping was enough that Big Tobacco knew it had to make a move. That is why in December 2019 the Pakistan Tobacco Company launched Velo. This brand of nicotine pouches was launched amidst great fanfare and was heavily marketed as well. Because this is not a product that burns, there is no regulation in Pakistan that governs it. Velo even tried to pull off a Coke Studio like move by introducing Velo Sound Station and quickly nicotine pouches also became commonplace.

“But there was always going to be more. Nicotine pouches were the first foray into launching non-tobacco products in Pakistan. The only problem was this was a product tailored to helping people quit. It was discreet and didn’t have any of the best elements of smoking,” explains our anonymous tobacco executive. “You just pop it in your mouth and that is it. There is no social element to it like smoking or vaping. It also takes away the allure of blowing smoke. But with people veering away from tobacco something obviously had to shift.”

Enter the Big Boys

Pakistan Tobacco Company was the first to move. Internationally British American Tobacco introduced their Vuse brand of e-cigarettes and vaping devices as early as 2013 when the trend of vaping was on the rise in the United States. In Pakistan they decided to launch it earlier this year, making it the first vape officially produced in Pakistan. Once again, thanks to fewer restrictions, they marketed it with a shabang pulling out all the stops from hiring dance crews at launch events to placing agents and free testers at vape shops.

Since the product is local and not imported by individual importers and businesses, the price of the product is also cheaper. In very quick time Vuse has gained traction and popularity in Pakistan. At the same time, Philip Morris has not been sitting idly by.

But their approach to the problem (or opportunity?) has been rather different.

You see Philip Morris lagged behind when it came to nicotine pouches. They have only recently introduced their Zyn brand, although they have brought it out with aplomb spending a hefty bit on marketing. And now, much like PTC, they are also bringing their own alternative to cigarettes. The only difference is that instead of bringing in their own vape Philip Morris has what is known as a heated tobacco product.

Internationally as well Philip Morris sells their heated tobacco under the IQOS brand name. This is not a vape. Essentially, it is a hand-held device a bit larger than the average vape that comes with a small pack of “Heets”. These are small filters with what looks like a tiny cigarette attached to them. You insert this butt into the device which then starts vibrating. After this, there is a period of around two minutes in which the device and the filter are active. The device heats the tobacco producing smoke without actually burning the paper or tar and other carcinogens in the cigarette. One would assume it is supposed to be healthier but as with all nicotine consumption it is not recommended by doctors. The IQOS device gives more of an effect of a cigarette than a vape does. It lasts around the same amount of time/puffs as a cigarette and you still get the feeling of buying a pack. It is significantly more expensive, with devices costing anywhere from Rs 30,000 to Rs 50,000.

But unlike PTC and their Vuse vapes, Philip Morris seems to want to market this as a more exclusive product. They have been undertaking an effort whereby they try to sell the product to a high-end market. These devices and heated tobacco are not new in Pakistan. People have been importing them or bringing them back from trips for some years now. But Philip Morris is now importing them directly from their counterparts in South Korea, which is making them significantly cheaper. While Vuse has the edge of being cheaper, more accessible, and vapes being more commonplace, it seems Philip Morris is trying to focus instead on creating its own niche.

The tobacco farmers

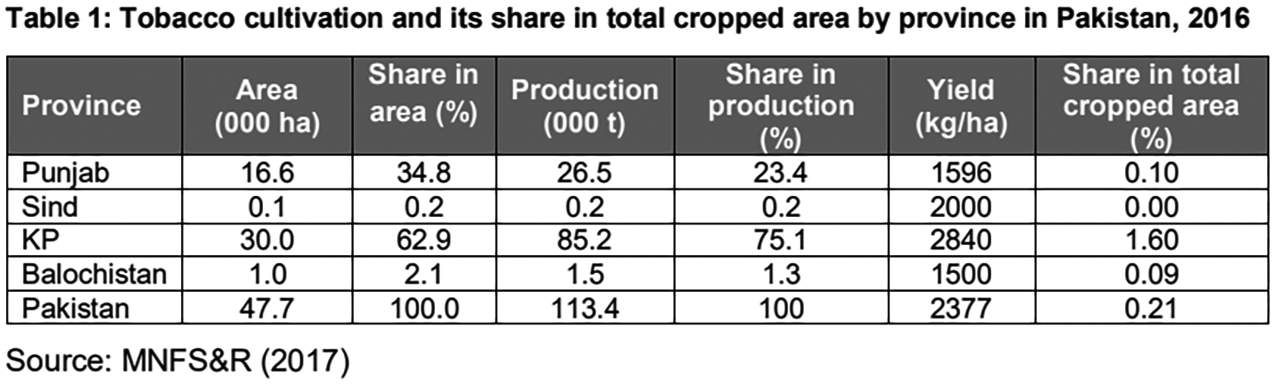

Pakistan grows a lot of tobacco. Tobacco is grown in all four provinces in Pakistan, but it is predominantly grown in KP where it is a major part of the local agrarian economy. KP’s provincial economy is pegged majorly to the growth of tobacco. More than 80% of KP’s population lives in rural areas, with agriculture accounting for around 30% of provincial GDP. Pakistan currently grows tobacco on some 50,800 hectares, with KP making up nearly 30,000 of these hectares.

It is one of those rare agricultural products where Pakistan is ahead of the curve. Over the more than 50,000 hectares on which tobacco is grown, Pakistan’s yield per hectare stands at nearly 2.3 tonnes per hectare with a total production of 113.6 million kilograms. In comparison, the world average production for tobacco is 1.84 tonnes per hectare. Meanwhile KP in 2021 produced 71.38 million kilograms on 28,089 hectares of land, giving an average yield of 2.5 tonnes per hectare — a 66% rise on the global average.

A report of the planning commission from 2020 explain how during 2000-16, the production of tobacco in Pakistan has increased at a rate of 1.90% per annum mainly because of the improvement in per ha yield (at 1.64% per annum) as area under the crop expanded at 0.26% per annum. In KP, where 63% of total tobacco area lies, the growth in tobacco area during 2000-16 was highest at a rate of 0.63% per annum, while in Punjab which contributes about 32% of the total tobacco area, growth in tobacco area was on a declining trend. The tobacco area in Balochistan is also declining from a very small base, while in Sind it is increasing also from a very small base. The highest growth in tobacco production also came from KP at 2.03% followed by Punjab and Sindh. The highest growth in per ha tobacco yield was in Punjab.

Now remember, most of this tobacco is purchased from the farmers by PTC and Philip Morris, with the smaller tobacco companies making up a very small proportion. There is no serious projected dip in cigarette manufacturing in Pakistan over the next few years but in the long run there might be a bigger shift towards non-tobacco nicotine products. When that happens, one of Pakistan’s more successful crop stories might face some problems.

Of course, we cannot quite say we’re sad about that. The reality that tobacco is a harmful substance that we should long have been rid of is very real. However, tobacco is here to stay for now. If we are to take any good from it we must encourage more growth that benefits farmers and is largely export oriented. Because there really is very little other benefit from its cultivation.

Would love to constantly get updated great blog