Pakistan is a country where the bureaucracy hardly gets reprimanded for their mistakes. So when the Prime Minister of the country offers stern criticism to the Federal Board of Revenue over something, it is meant to be taken seriously. A few days ago, PM Shehbaz Sharif, while talking to his federal cabinet called the track and trace system put in place in 2019, a complete fraud with the nation.

He said that it was a cruel joke that was played with the nation and demanded through investigation of the implementation of track and trace. Since then the track and trace system has made the news quite often. An inquiry committee was formed and up until the filing of this story, two esteemed officers, one of them the current chairman of the Federal Board of Revenue, were found responsible for the “delays” in the enforcement of the track and trace system.

To understand what went wrong with what was promised to be a revolution in sales taxes, Profit followed the tracks of the implementation of this system. What unfolded was nothing short of an indictment of the Pakistani bureaucracy. A tale of red tape, inefficiency, kickbacks, controversies and allegations.

What is Track and Trace

For readers who are not yet aware of what this system does, following is a simple explanation of what track and trace does:

Manufacturers frequently underreport their production figures to avoid taxes, initiating a problematic cycle. For instance, let’s consider a hypothetical scenario: a fertiliser manufacturer produces 500 bags of Urea, yet the demand stands at only 400 bags. If all 500 bags enter the market, oversupply occurs, leading to price depreciation. To circumvent taxation on each bag sold, the manufacturer opts to report a production of 400 bags officially, concealing the surplus 100 bags, which are then sold at lower prices without tax liability.

This practice generates artificial shortages, prevalent across various industries, including Urea, cigarettes, cement, and sugar, which are also prone to smuggling operations. Recently, the FBR’s customs department intercepted significant quantities of urea and sugar in Balochistan, amounting to a total value of Rs 392 million. Such instances underscore the pervasive nature of underreporting and its ramifications, contributing to an undocumented shadow economy estimated to range between 40-80% of Pakistan’s GDP.

Addressing this issue, the Track and Trace (T&T) system advocates for direct tax collection at the production source. In the case of fertiliser production, for example, the government implemented a T&T system requiring manufacturers to invest in stamping each bag with unique identifiers. These identifiers are scanned upon sale, with data transmitted to the FBR for taxation based on actual production figures.

T&T solutions, commonly utilised globally, aim to streamline tax collection processes. However, the effectiveness of such measures, particularly in industries like fertiliser, cigarettes, cement, and sugar, warrants examination. Has the implementation of the T&T system yielded tangible results, and how have these industries responded to regulatory interventions? These are crucial questions that merit further exploration.

Essentially, the system would fix more than 5 billion stamps on various products at the production stage which was meant to enable the FBR to track goods throughout the supply chain. Essentially, industries would stamp their products right after packaging them and then scan each one before selling it so that the data for production volumes goes directly to the FBR.

The system was first put in place in Pakistan in 2019 and has alluded to a thorough implementation despite the passage of 5 years. The Prime Minister, most recently, had asked an inquiry committee to look into the reasons as to what is the delay. Alongside the Prime Minister has taken part in his fair share of belittling of the system itself. The inquiry committee has come forward with the conclusion that the awarding of a contract worth Rs 25 billion was due to mismanagement by the project director and two former chairmen of the FBR. The answer might suffice for the federal cabinet but in our eyes, it raises more questions than it answers. And this is where the story begins.

Let us start with who this vendor is. When awarding the contract, the FBR took 2 years to decide who the vendor was going to be and the process which was followed exposes the nature of this problem.

The implementation and the first round

Many, to this day, believe, or are made to believe that track and trace was a project brought about by the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf (PTI) government. It is also believed that the reason the system could not work is because of the change of governments in 2022 and political vindication of subsequent ruling parties.

However, that is far from the truth. The system was not only a part of the IMF’s reform agenda that Pakistan agreed to for its 22nd IMF program, but was also carried out and sponsored by the World Bank under its Pakistan Raises Revenue (PRR) program.

The backlash from the industry was almost certain when the track and trace started. And that could be seen from the onset of the system. When the FBR released a public notice for a licence that was to be awarded to a vendor who had the requisite technical capabilities, problems started ensuing.

The licensee was supposed to be responsible for end-to-end installation and operation of a Track and Trace System/ Solutions connecting manufacturing sites and import stations to the FBR’s Central Control Room (CCR). Initially the system was to be implemented only on the sale of tobacco.

A total of 13 bids were received for the said vendor by the FBR and upon the criteria set by the FBR, one was chosen to be the licence. The winner of the licence was a consortium of the following four companies. National Radio and Telecommunication Corporation (NRTC), Evolution Track and Trace (Pvt) Ltd, INEXTO (Switzerland), and PERUM PERCETAKAN UANG RI (Indonesia).

However, there was one peculiarity in the process. According to the bid evaluation report, the price offered per 1000 stamps was taken as the eventual selection criteria. In this, the NRTC consortium had provided a price of Rs 0.731/ 1000 stamps. For context, the next best bid by NIFT was at Rs 868/ 1000 stamps, almost 1200 times more.

The NRTC later contended that the price in its bid was an accidental slip, the real price it wanted to extend was Rs 731/ 1000 tracking stamps. The excuse was hastily admitted and the licence was awarded however, the NIFT consortium, consisting of Opsec Security Limited, Security Papers Limited and Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda, S.A (Portugal), took the matter to court and got the licence set aside.

The Islamabad High Court ruled in favour of NIFT and Authentix, another bidder who had taken the decision of the FBR to the court. Hence a rebidding was in order.

Round two, somehow worse than round one

One would think that if a process is done for the second time, it would be done more diligently, however somehow the FBR managed to make it much worse the second time it carried out the bidding.

Upon the completion of evaluation of bids AJCL (Pvt) Ltd got the licence but this time there were more problems. Starting off as a company under the Jaffer group of companies, it was only as late as 2017 that AJCL became a separate company. Even then the directors of the company remain the members of the same family.

A conflict of interest?

AJCL also owned the entire shareholding in AJCL Global Holdings Limited (registered in the United Kingdom) which in turn owned 75% shares in Claiser Trading Limited (registered in the United Kingdom in 2018). Claiser Trading Limited is said to have established an office in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates (UAE) and was trading under the name of Claiser Trading FZE. Claiser Trading FZE had documented trade ties with the sugar industry in Pakistan.

This obvious conflict of interest was taken to court once again by two of the other bidders because it was against the terms of the Invitation for Licence (IFL). In order to avoid conflict of interest between the licensee and industry sectors of the goods, clause 4.7 of the Invitation for License (IFL) required the bidders to provide a declaration and full disclosure demonstrating that the applicant has no material conflict of interest with the respective four industry sectors of the goods. Apparently upon review of the documents provided by the AJCL, no such conflict was highlighted by the Licensing Committee headed by Karamatullah Khan Chaudhary.

In order to prove this claim against AJCL, two bills of lading dated for consignments of ethanol (a byproduct of sugar) showing Claiser Trading Limited as the consignee and Shakar Ganj Limited, a sugar mill in Pakistan, as the shipper were presented as evidence.

But this is not where it ends. Let us go back to where AJCL comes from. AJCL Pvt Ltd, for the longest time was a family owned business of none other than the famous business family and conglomerate Jaffer group. In 2017, AJCL was declared as a separate business entity with some share of the family still in the business. But more than shares in AJCL, it is a question of influence. The kind of influence on direct or indirect stakeholder can have on such a process. To this day, the members of the board for AJCL are certain members of the Jaffer family.

For readers who do not know, the Jaffer family/group is one of the biggest conglomerates and has a stake in almost every major industry in Pakistan. One might remember the family’s name from a harrowing murder that a member of the family committed in 2021, but the businesses of the family go far beyond any shame that a murder can bring to the family name. For example, in the pretext of track and trace, Jaffer group is directly involved in the construction business with its company Murshid Brothers (Pvt) Ltd making it privy to the cement industry. Jaffer Agro Services, also trades in and supplies fertilisers in large quantities to agricultural clients. Moreover, the group is directly involved in the import of fertilisers within the country.

The link between the companies can also be established from the fact that during the first round the bidder referred to by the name of AJCL was also a consortium between Athentix US, Jaffer Brothers and AJCL. However, when bidding for the second time around, Jaffer Brothers was replaced by MITAS Corporation. Which brings into question the involvement of the Jaffer brothers. It was argued that this makes all the bidders questionable. NIFT for example is itself a consortium of six banks, some of which have cement subsidiaries. The argument is fair, yet somehow it does not refute the link and in turn the conflict of interest.

But that is a rather indirect relationship. Reliance IT, one of the petitioners against the award to AJCL, makes the case that AJCL’s own website shows that it has long standing relationships with some of the leading producers of rice, sugar and wheat in Pakistan. AJCL itself admits that it is actively involved in the indenting, import and export of several commodities. The list of its clients includes a few sugar mills. How could the FBR have overlooked that?

Consultant vs Consultee

The petition by Reliance also pointed towards irregularities in the process of selection of AJCL, it stated that for choosing the firm with the best technical capabilities the FBR was supposed to hire a consultant on the guidelines given by the World Bank. However, the FBR, set aside the World Bank process which involved tender and bidding and unanimously selected one firm for the purpose namely IDECO, a South African Company. The IHC ruling categorically confirms that the appointment of IDECO was not in line with the principles.

Reliance IT, in its petition made the case that the purpose of bringing in IDECO was to select AJCL and it did so by awarding it higher technical points. It is important to note that in the round one of bidding, when IDECO was not the consultant, the technical points given to Reliance were the highest while others closely followed. However, the second evaluation showed that AJCL was leaps and bounds ahead of the others in its technical capabilities. 33 points higher than Reliance (out of total 160) and 22 points higher than the second best NIFT were awarded to AJCL in the process. This remarkable improvement in AJCL’s technological capabilities over the span of only six to eight months was something that NIFT and Reliance were not buying.

Upon complaint to the Grievance Resolution Committee (GRC) of the Public Procurement Regulatory Authority (PPRA), it was maintained that the criteria to award these marks/points was confidential and could not be revealed.

Missing UIMs

Another and perhaps the most important contention of all was regarding the Unique Identification Markings (UIM). Readers who have had an experience with tobacco or distribution-stage wheat or Sugar might be familiar with a small sticker that has started to appear on cigarette packs and other commodities, ever since track and trace has been put in practice. That sticker in essence, along with other hidden components is known as the UIM.

The clause 3.5 of the IFL provides that the UIMs shall utilise core material which must be made of an anti-tampering substrate so that any attempt to tamper with or to remove a UIM will crumble a portion of the UIM, which will be clearly and immediately recognized. Clause 3.7 listed the minimum security features that the UIMs were required to contain. These security features included one overt material security feature visible by the naked eye and one semi-overt material security feature visible through a simple and very low cost device. Clause 3.9 requires a bidder to provide specimens of these UIMs with details including full description of the security features. IFL requires real-time specimens to be presented with details and full description of the security features to the FBR. According to the IFL, these UIMs were to be given marks out of 30.

In an alarming revelation Reliance stated that the FBR officials refused to accept the box containing these UIMs along with the application, yet somehow in the evaluation report, they themselves gained 29.3 marks. This meant that the FBR gave them lump sum marks making the whole marking process contentious.

Since the account of events quoted by Reliance went against the IFL. The exact reason for which the first round of bids was aborted. Surprisingly, during the court proceedings, the FBR conceded that it did not actually collect the samples from 3 other bidders due to late submission on account of interference by costume (Reliance had to import its stamps).

There is also a comic value to the fact that the customs seizure lasted up until the day of submission deadline after which the stamps were released. But how did FBR give points? It was stated that the samples were not of as much “paramount importance” but rather the evaluation framework upon which the overt and semi-overt features worked.

Coincidentally, AJCL’s stamps were not seized by the costume authorities and were released well before the deadline granting them the most marks. Despite having violated the terms of the IFL, and admitting to violating these terms, the IHC ruling remained in favour of the FBR.

In fact, despite some serious allegations against AJCL, both the petitions were dismissed by the IHC due to lack of evidence. It was also noted by the IHC that since the petition filed was against the Grievance Resolution Committee, and its oversight in responding to the complaints of the petitioners, the court did not find the GRC guilty of doing that. Whether the awarding of licence to AJCL was justified, or hiring of IDECO as the consultant to evaluate the bidding process was legal are entirely different cases.

Profit also found out that an appeal against the judgement was filed in the Supreme Court of Pakistan, a short time after the judgement. To this day, not a single hearing has taken place on the matter. Hence, AJCL got the licence of installing and operating the track and trace system for Tobacco, Cement, Sugar and Fertiliser industry.

Flaws in the implemented system

One of the main reasons that the FBR gave for expediting the process, in bypassing due procedure for bringing in a consultant and denying complaints by competent bidders, was the urgency with which Pakistan had to put the track and trace system into place.

The FBR maintained that the IMF wanted this system in place before June 2020 but due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the IMF had relaxed the deadline till June 2021. Since both these cases were heard very close to the provided deadline, sources close to the development believe that Pakistan could not have afforded a renewed bidding process, in fact that is the very reason for which no follow up cases had been filed.

Anyhow, with all its question marks and flaws, the system was put into effect by the AJCL consortium. But it became very clear right away that making the system operational as quickly as possible was never FBR’s priority. The board wanted the nod from the IMF for its review back in the day and once it got that nod, the track and trace was at the mercy of the wind.

The system faced quite a backlash when it was put in place. Pakistani producers are not in the habit of sharing their numbers and when someone asks them to do it, they are defensive.

An incident of dispute occurred with Khyber Tobacco. The AJCL consortium found itself in dispute with Khyber Tobacco over who would pay for the adhesive in the stamp, and the release of a large consignment before implementing the TTS. A case that was later set aside by the IHC since the IFL clearly made it the licensee’s responsibility.

But it became clear that the lack of quality in the adhesive material ingrained in the UIMs provided by the AJCL was going to cause problems especially in the sugar and fertiliser industry. It was found that the specifications of adhesive material as specified in the IFL were not met and stickiness to polymer bags was a bone of contention.

FBR in its directions clearly stated that the tax stamp needs to be applied on the surface of the product in a location that is most accessible based upon the presentation of the bags to the applicator.

On the other hand, manufacturers also need to provide high speed internet connectivity so that once a stamp is scanned the data goes directly to the board. This then also requires a suitable location for the installation of equipment, an isolated power terminal point of 220v 15 Amp and floor space for the Unique Identifying Mark applicator that is used to put the stamps on. And the industry which already needed an excuse to not have its production traced would never go out of their way to install a stamp that was faulty.

Viral videos on social media platforms have also made the case for the questions raised on the TTS. Videos with gentlemen placing fake UIMs on counterfeit cigarette packs with the help of their saliva bring into question not only the licensee but the authority (FBR) responsible to carry out this tracking and tracing. Is the industry investing in a flawed technology altogether?

In November 2022, the fertiliser sector banded together to complain about problems with the stamp system. In a letter to Federal Finance Minister Ishaq Dar and Chairman FBR Asim Ahmad, fertiliser manufacturers of Pakistan Advisory Council (FMPAC) claimed that the technology being used by the FBR (which the board had strongly armed the industry into investing in) did not work. They claimed, for example, that less than half of the stamps actually scanned even though the scanning efficiency was supposed to be 99%.

Where do we stand

According to media reports, one of the proposals put forward by the cabinet inquiry committee is to terminate the licence of the vendor AJCL and bring a new “world class” vendor with the requisite technological expertise. Infact AJCL itself employs the services of Authentix a US based company, specialising in these services.

It is important to note that of the initial 13 bidders, almost all had the services of a foreign company except for NRTC, which was using the technological expertise of SEPL, a state owned enterprise. The question is, how will this hypothetical world class vendor be selected?

It appears that after wasting a vast amount of industry and World Bank money, Pakistan is back to square one in its implementation of the track and trace system.

The actual problem

Our story about Track and Trace is pretty much over. And this is once again an example of Profit beating the same drum it always does time and again, but it is important to make this point in this problem. Scheme like Track and Trace will only be effective when the core problem in our taxation philosophy is addressed.

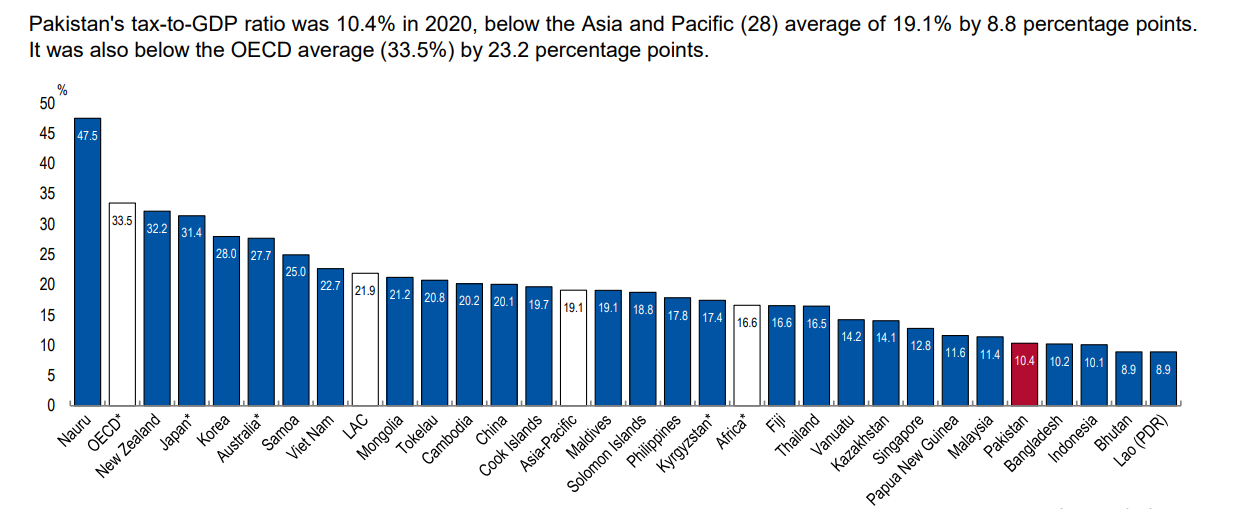

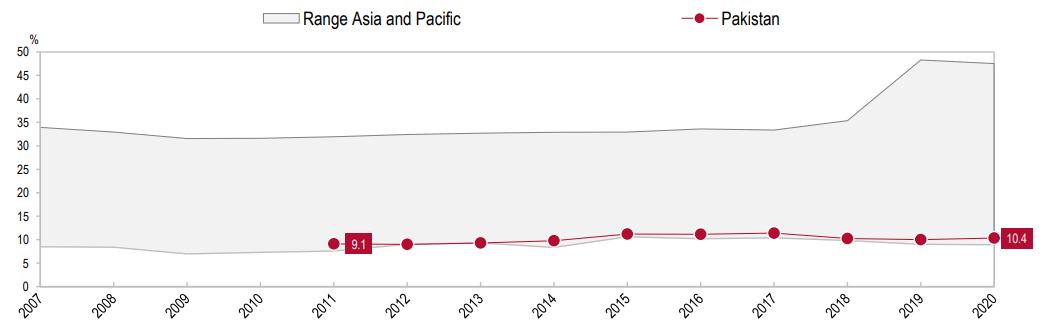

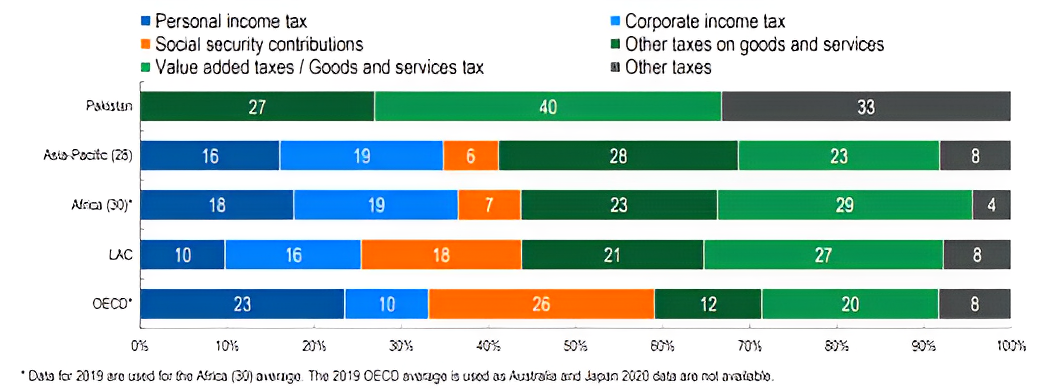

The real problem is that Pakistanis are taxed unfairly and those that should be paying the lion’s share end up paying nothing. Just take a look at Pakistan’s tax structure. Tax structure refers to the share of each tax in total tax revenues. The highest share of tax revenues in Pakistan in 2020 was derived from value added taxes / goods and services tax (39.8%). The second-highest share of tax revenues in 2020 was derived from other taxes (33.3%).

In comparison to Pakistan, countries in the Asia-Pacific region only collect about 23% of their taxation from goods and services taxes — meaning Pakistan’s average is almost double. Why is this the case? The biggest reason of course is that taxation in the country is centralised. The FBR collects almost all taxes (even the ones that should be collected by provinces under the 18th amendment) and then those collections are then given to the provinces in the form of the NFC award leaving the federal government with very little spending money. In an earlier interview former Finance Minister Dr. Hafiz Pasha, while talking to Profit, lamented that, “We as a country have failed to implement the beautiful 18th amendment. The implementation has been slow and weak.”

Since the share of the provincial governments, under the NFC awards, over the last few years has been increased from 40% to around 57%, it has provided the provinces with very little incentive to develop their own revenue sources. Despite having access to the two biggest cash cows, services and agriculture, the share of provincial tax revenue is close to 1% of the GDP. “You would be surprised to know that the corresponding number for Indian provinces is around 6% of the GDP, with similar fiscal powers,” says Dr. Pasha.

The solution of course is right in front of us: devolution. More than just being a third tier of democracy, having a local bodies system means having a new economic process. In essence, it is not just a new administrative stratification, but also involves the dispensation and spending of money. Things such as education and health that people automatically look towards the provincial government for would now be handled by local representatives. Perhaps most crucially, the ability of local governments to collect taxes and release their own schedule of taxation allows them to make their own money and spend it on themselves rather than waiting for the benevolence of the provincial or federal government.

Of course, devolution to local governments is still a long way away. In the meantime, the Track and Trace system needs to be better implemented with proper feasibility studies before tech is brought into the country. Otherwise this will be another in a long list of failures where the state will be unable to improve our tax collection mechanisms and widen the cast of its net.