You wouldn’t have thought about it, but a lot was riding on the Indian election for Pakistani rice farmers. Let us explain.

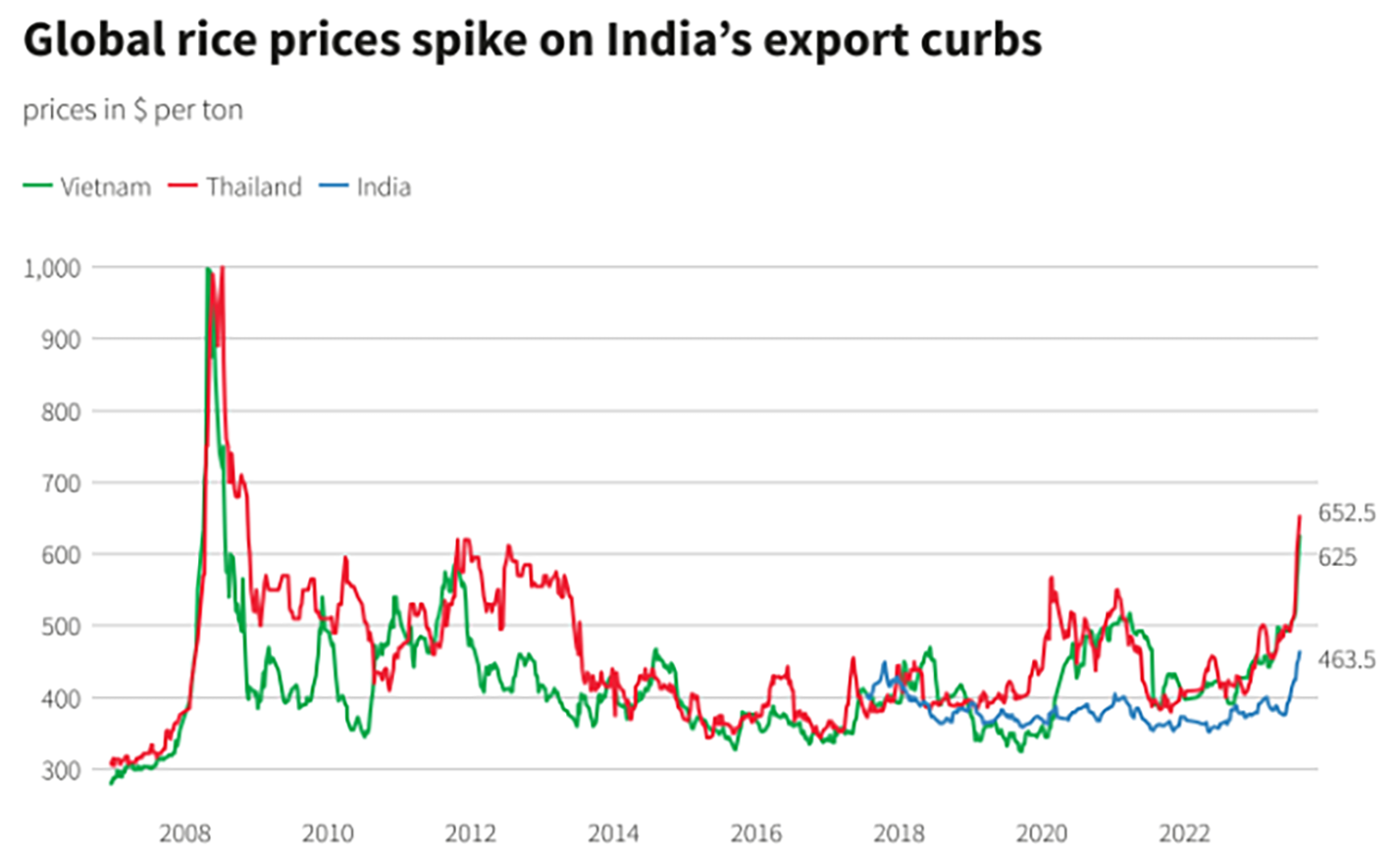

Last year, the Indian government found out the country’s rice crop was under threat. This was at a time when food inflation was soaring in India, and shortages were being felt on the market where the prices of rice were very high. The government felt exporters were greedy and wanted to sell on the international market because they got better prices there. To prompt them to sell domestically in the middle of election season, the Modi Administration decided to ban India’s export of rice except for in the Basmati category.

This was a major opportunity for Pakistan, which saw the chance to step up and partially replace India for those countries dependent on external sources for their rice. Except now India is likely to cut the floor price for basmati rice exports and replace the 20 per cent export tax on parboiled rice with a fixed duty on overseas shipments, Indian government sources said last week, in an apparent move to help India retain its market share against Pakistan.

So what happens now?

India’s market position

India is a massive exporter of rice. In 2022, the neighbouring country exported over 22 million tonnes of rice to the entire world. As the single largest exporter of white rice in the world, India control’s a massive 40% of the global market for rice providing different kinds of rice that many other countries in the world are heavily dependent on for their caloric intake.

But then came 2023. India nput a ban on the export of all kinds of rice except the aromatic and high-end Basmati variety. The ban comes in response to soaring rice prices in India and a general food inflation crisis that was brewing in the country. As a result, the international rice market suddenly finds itself short on more than 10 million tonnes of rice. With a global food crisis already about to reach crescendo because of the Russia-Ukraine war, rice importing countries and international organisations are suddenly faced with a concerning question: how will this massive shortfall of rice be met?

The news of India’s rice ban resulted in supermarkets facing panic buying all the way in the United States and other countries that rely on Indian rice. Some other countries that are also exporters may also follow suit with a ban to protect their own domestic markets. It was also an incredible opportunity for Pakistan.

The opportunity

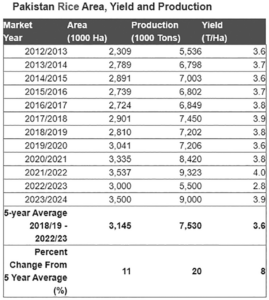

While India might be the largest exporter of rice with Thailand at a distant second place, Pakistan is number four on the list of largest rice exporting countries in the list with Vietnam in the middle at number three. In 2022, Pakistan’s total rice production was just over 5.5 million tonnes and the total export was around 3.5 million tonnes.

China, the Philippines, and Nigeria are primary purchasers of rice. Meanwhile, nations such as Indonesia and Bangladesh, often termed “swing buyers”, increase their imports when facing domestic supply deficits. Rice consumption is not only high in Africa but also on the rise. For countries like Cuba and Panama, rice is a principal energy source. In the previous year, India shipped 22 million tonnes of rice to over 140 nations. Out of this, the more affordable Indica white rice accounted for six million tonnes. For context, the global rice trade is estimated at 56 million tonnes. Thailand, Vietnam and Pakistan, the world’s second, third and fourth biggest exporters, respectively, have said they are keen to boost sales since demand for their crops has been rising after India’s ban. According to initial reports there is a major role for Pakistan to play in this crisis. But will the Pakistani government bite? Pakistan, recovering from last year’s devastating floods, could export 4.5 million to 5.0 million tonnes according to an official with the Rice Exporters Association of Pakistan (REAP). But already REAP is worried that since food inflation is already pretty high in Pakistan, the government might not be so keen on exporting rice since it will become expensive on the global market.

Did it work?

Sort of. Rice exports from Pakistan for the financial year that just ended last month may touch the 5.8 million tonnes mark mainly because of favourable weather, availability of farm inputs, and the Indian ban on non-Basmati rice exports. Data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics suggests that rice exports crossed the 5m tonne mark in 10 months (July-April FY24), earning $3.4 billion, compared to 3.2m tonne exports worth $1.8 billion made during the corresponding period last year.

It was a pretty simple equation. Pakistani exporters focused on non-Basmati rice and met the shortage that was caused because of India’s ban. As a report in Dawn states, “this phenomenal achievement has been made possible due to a 32 per cent volumetric increase in exports of non-Basmati and a 24pc increase in Basmati. On average, the Basmati export price during the 10 months remained $1,141 per tonne and non-Basmati $573 per tonne.”

The presence of India on the international market is deliberately bleak. Non-Basmati Indian exports nosedived to less than 1m tonnes in volume this year from 16.4m tonnes a year earlier. Indian rice traders termed the export ban imposed by the Modi government as a political rather than a commercial decision. El Nino, fear of political fallout, inflation and general elections were put forward as the major reasons behind the move despite a more than historical, current buffer stock of 54m tonnes against the approved limit of 14m tonnes. However, Indian Basmati exports touched a new high of 5.2m tonnes from April 2023 to March 2024 (Indian financial year) despite strong tailwinds in the early part of the Kharif 2023 season, such as devastating floods in the Indian Punjab, and strong headwinds, such as the compelling Ukraine war and Red Sea disturbances. Pakistan Basmati rice export during the corresponding period (April 2023 to March 2024) has been 0.73m tonnes which is 14pc of Indian Basmati export. But Pakistan’s per tonne earning was $1,137, which is 3pc higher than Indian price.

Modi changes course

But there was a catch to all this. India was always going to be back to take its position as top dog once the crisis was over. This was further exacerbated by the underwhelming electoral results garnered by Prime Minister Modi’s BJP. As a Reuters report points out, Modi is facing a policy conundrum after losing ground in the recent election: how to control food inflation without resorting to export curbs and more imports – steps that have angered farmers, a sizable voting bloc.

After all, the initial ban had been an effort to clamp down on prices, but the measures did not go down well in the countryside, where more than 45% of India’s 1.4 billion people make a living from agriculture. The BJP, which held 201 rural constituencies in the 543-member parliament, retained only 126 of them in the mammoth April-May election, according to a voter analysis.

Some decisions are imminent, like easing export curbs on at least two commodities to begin with, the experts said. Other longer-term measures could also be considered, like boosting crop yields and raising government-mandated support prices by bigger margins, they said. The government announced on Wednesday that it would increase support prices that are offered for summer-sown crops, but the raises were unlikely to placate farmers.

What can be done?

This is what it comes down to. The opportunity Pakistan had in 2023 was always going to be a temporary thing. Pakistan cannot come near fulfilling the world’s rice demand. The total shortfall from India’s decision to ban the export of varieties other than Basmati (which is a big seller) has caused a 10 million tonne shortage. Pakistan’s overall production was only 5.5 million tonnes last year. But that was a bad year because of lasting damage and water logging from the 2021 floods.

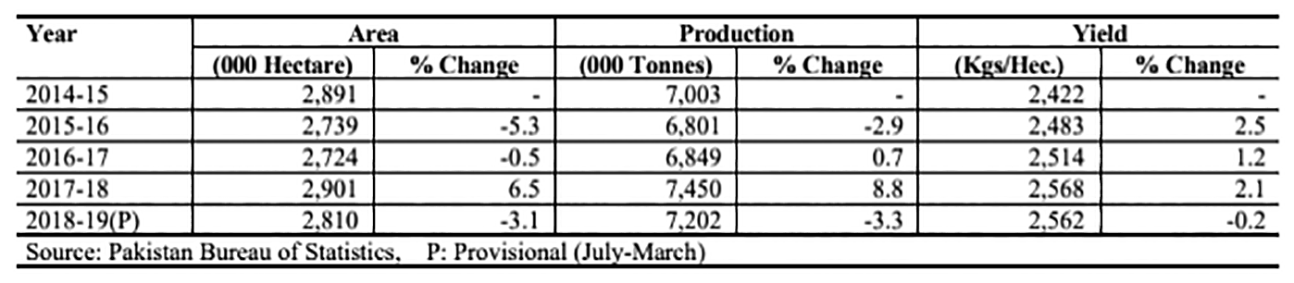

The rice sector in Pakistan is extremely important in terms of export earnings, domestic employment, rural development, and poverty reduction. Rice is an important food as well as cash crop in Pakistan. It accounts for 3.0 percent of the value added in agriculture and 0.6 percent of GDP. After wheat, it is the second main staple food crop. During 2018-19, rice crop area decreased by 3.1 percent (to 2,810 thousand hectares compared to 2,901 thousand hectares the previous year). The problem is that for any long-term change Pakistan needs to make significant amendments to its agricultural systems. This year could have been a great opportunity to find new markets for the export of rice but instead Pakistan will only be a stop-gap solution at best because it is uncompetitive.

Despite significant improvement in yield during the 2000s, Pakistan has lost the competitive edge in basmati as indicated by its plummeting shares in total basmati export from 46% in 2006 to less than 10% in 2017, which was conveniently picked up by its competitor India. Pakistani basmati exports also declined by 45% in absolute terms during the period. This declining competitiveness is due to a number of factors that favoured India than Pakistan during the period, including stronger technological innovations which gave higher productivity growth in basmati that have more elongated kernel size without aroma, and lower production costs due to high input subsidies.

According to a 2020 study of the planning commission, for Pakistani rice to become competitive on the international market it needs six interventions: i) gradual shifting to mechanical rice transplanting which is needed for increasing plant population and long awaited productivity enhancement issue of the area; ii) diffusion and adoption of high yielding varieties in the area which is required to replace the varieties like basmati-386, Supra, Supri, etc.; iii) introducing improved crop management practices as large gap between average and progressive farmers’ yield and associated variations in crop management practices can be noticed across farms; iv) shifting to rice combine harvesters which are essentially needed to control harvest and post-harvest losses in milling and address the problem of burning of rice straw; v) introduction of paddy drying at farm level in order to improve the quality of paddy and its by-products; vi) introduction of rice bran oil to diversify rice value chain.