Last week we talked about onions. A hard vegetable that has a delicate constitution when it is in the growing stage, but which proves to be a tough nut after harvesting that can weather more than a few bumps and scrapes and has a significantly longer shelf life compared to other vegetables.

Significantly more delicate and equally if not more important to the culinary requirements of Pakistan is the tomato. Botanically categorised as a fruit not as a vegetable, it is the second major component of salan and is yet another crop that has suffered from more than the recent floods. But just like it is much more delicate compared to the onion, tomatoes have a more complex place in Pakistan’s agricultural landscape and it is a crop that has shown signs of hope particularly in the last couple of decades.

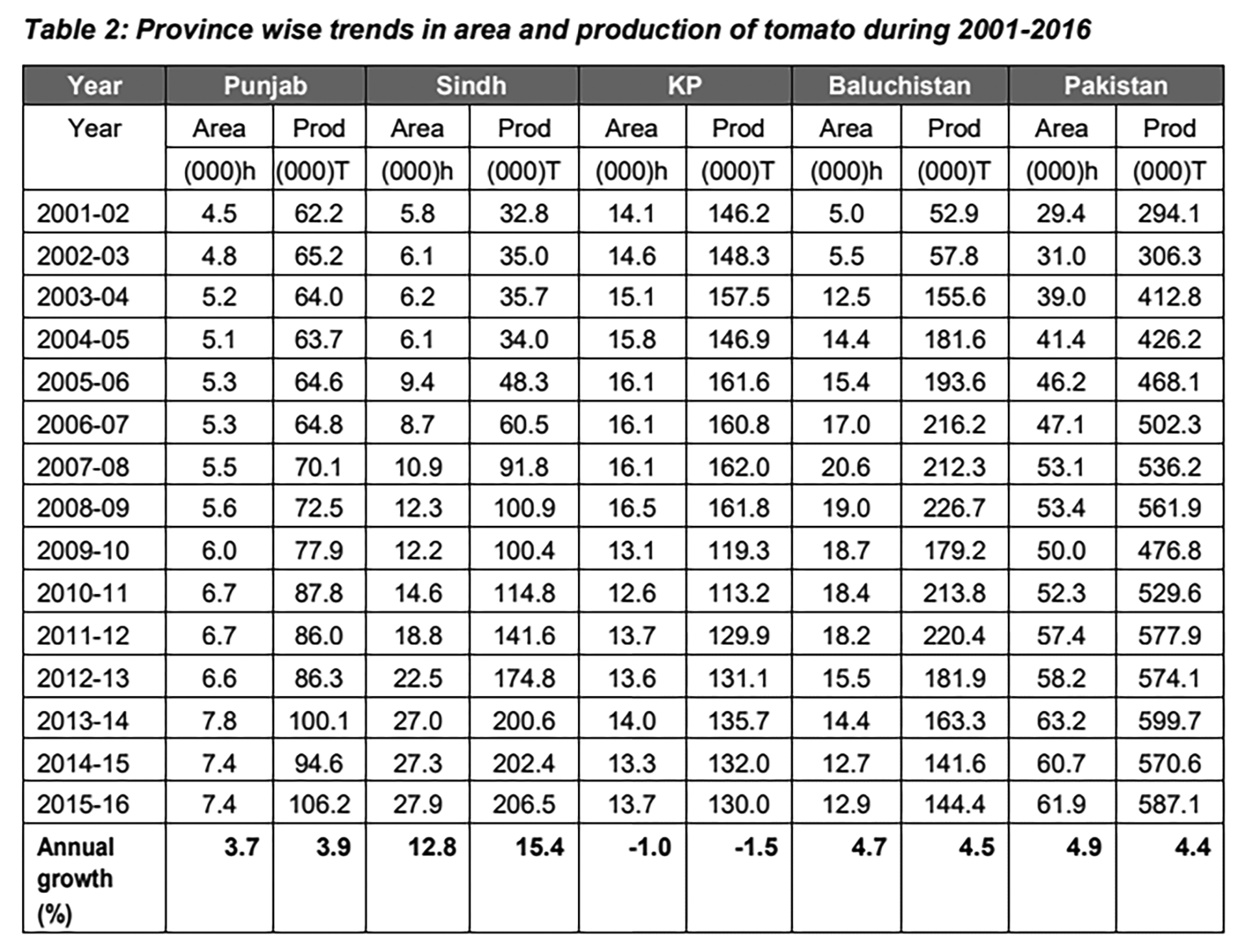

Unlike onions, tomatoes grow on a significantly smaller scale in Pakistan. Their story too has been very different. Since independence up until the 1980s, they were grown in Pakistan for sure but in very contained areas. From the 1980s onwards, the area under yield for tomatoes grew but at a sluggish pace. It was at the turn of the century that more importance was paid to the little red fruit that is so vital in our cooking. Between 2001 to 2012 the area under yield and production both nearly doubled. However, after staying stable for a couple of years, the area that is farmed for tomatoes has taken a hit and has continued to do so since 2014.

Yet the story is not just one of hope. There are also the typical structural inefficiencies of Pakistan’s agricultural map. For example, despite tomatoes being a major culinary component, Pakistan is a net importer of tomatoes and tomato products. For a country that requires tomatoes to cook nearly all of its staple dishes and is obsessed with ketchup (using it with everything from fries to pakoras) that is a shockingly dismal statistic. Especially considering that in the past couple of decades there has been a very marked increase in the domestic demand for tomatoes in Pakistan — according to the FAO Balance Sheet data, per capita per annum consumption of tomato in Pakistan during 2013 was 4.8 kg, which is one of the lowest in the world. However, the growth in per capita consumption of tomatoes in Pakistan is quite high. It has increased from 1.86 kg in 2001 with an average growth rate of 7.5% per annum.

According to a 2020 report of the Planning Commission of Pakistan, the tomato trade deficit of the country has ballooned overtime. It fluctuated widely over the course of the 2010s, particularly in 2016 and 2017 but has resoundingly remained in the net negative. A similar story exists on the growth end of things, with very little investment being put into tomatoes in the country.

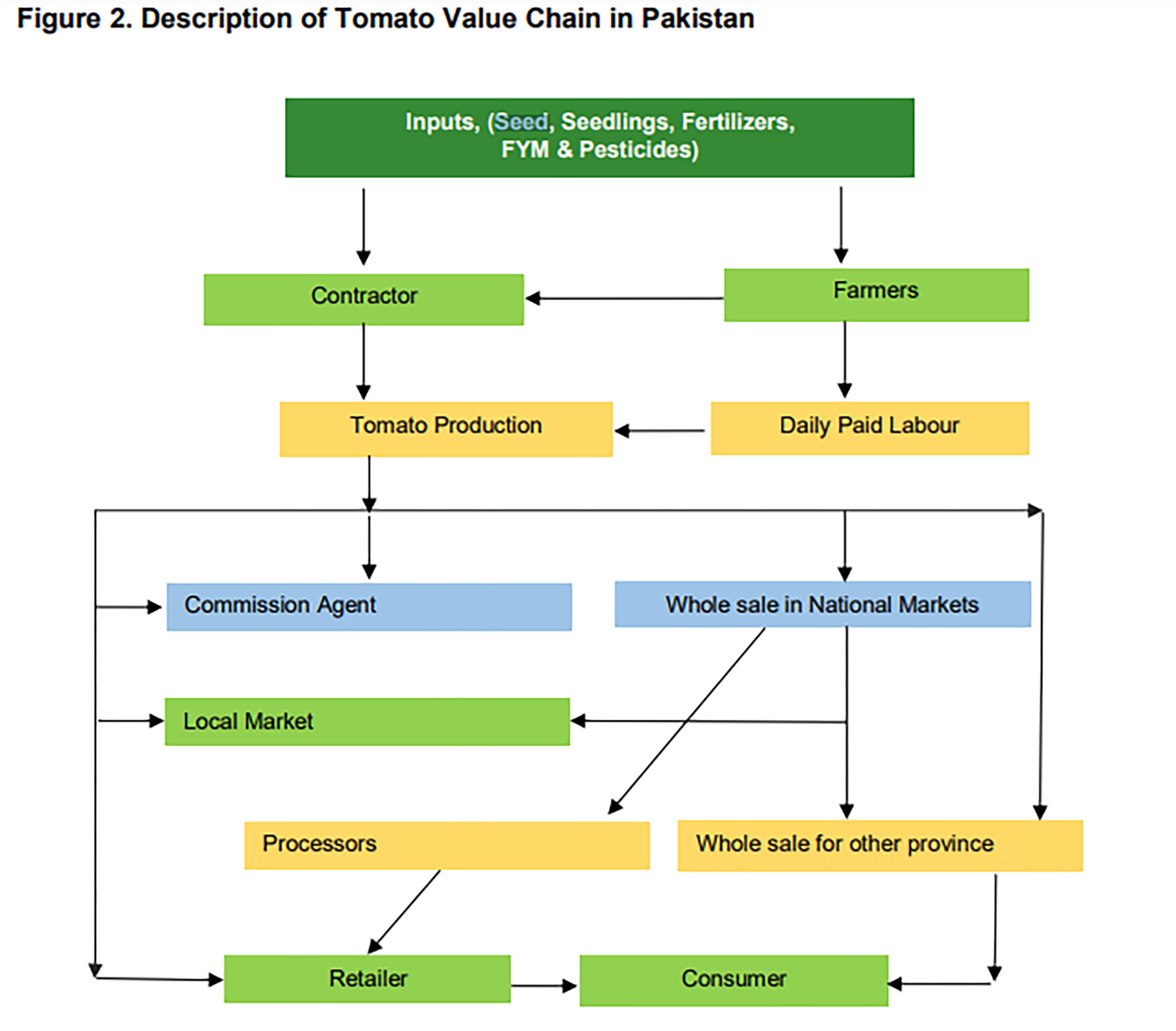

The reason, of course, is that tomatoes are not a particularly safe crop in Pakistan. Unlike crops such as wheat and cotton, there is very little concept of a support price. In addition to this, tomatoes are dangerously delicate for farmers to invest in. Even though they are in constant demand, for their farming to be profitable modern techniques are needed. At the same time, there are larger structural reasons that need to be discussed to fully understand the stature of this complex crop.

The tomato potential

Two of Pakistan’s neighbours lead international tomato production. China and India are the two countries that produce the most tomatoes in the world. In comparison, Pakistan ranks 33rd among this list. To understand the size of the market, global export of fresh tomato is worth $8.8 billion, while the export of tomato and its products has reached over $13 billion.

For Pakistan to become a major exporter of tomatoes would take a lot. As has been pointed out, tomatoes are a delicate fruit and require very specific conditions post harvest for which we do not have the capacity. There are not enough storage facilities, enough transportation vehicles, and experience to turn Pakistan into a major exporter. On top of that, the tomatoes produced in Pakistan are of the shorter, more elongated variety rather than the more desirable round tomatoes and cherry tomatoes.

That, however, is also not what we mean to suggest. Even though Pakistan cannot become a major exporter, what it can do is become a significant exporter. Currently, our major markets for tomato exports are the middle east and Afghanistan. There are other markets we can look towards.

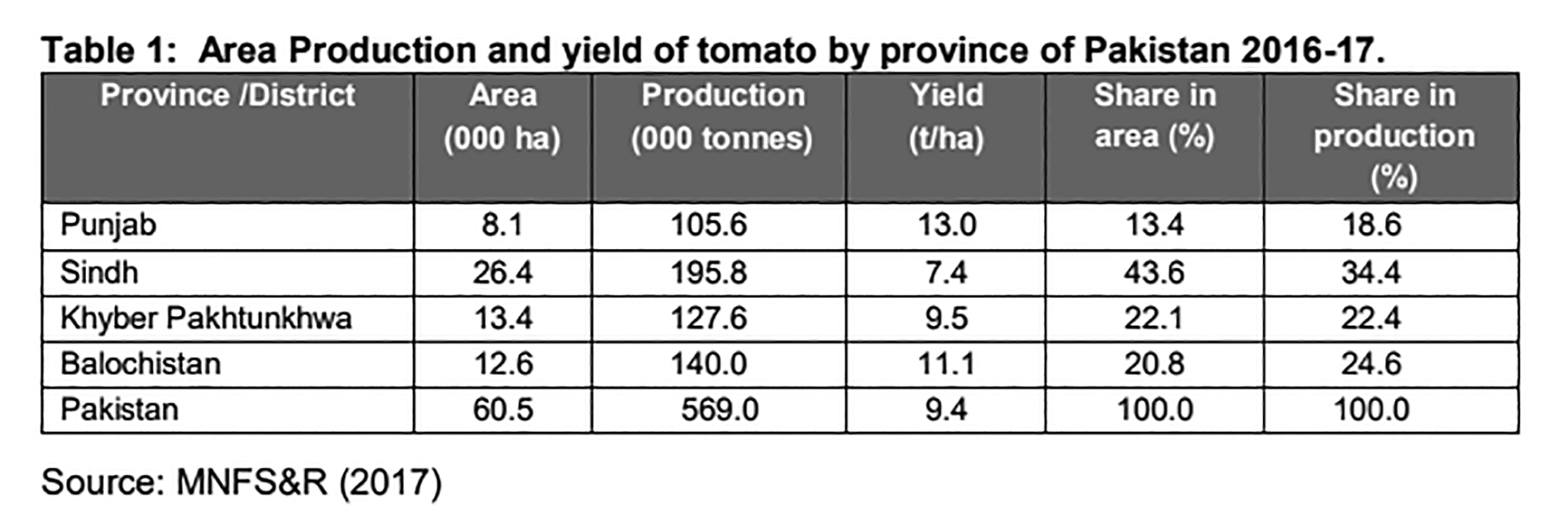

At present, with the latest data available from last year, Pakistan has a total area of around 61 thousand hectares under cultivation, with annual production for this area somewhere around 569 thousand tonnes giving an average yield of 9.5 tonnes per hectare. This is, to put it mildly, abysmal. Not only are we not in a position to export, it would be a pretty big deal if we were simply able to meet our own net needs for tomato and tomato products.

In comparison to Pakistan’s average yield of less than 10 per hectare, the global production of tomato is about 182 million tonnes obtained from 4.8 million ha with an average yield of 38 tonnes per hectares. That means Pakistan is behind by around 400% on the per area yield that it gets from its tomatoes.

As the earlier mentioned report of the planning commission laments, on account of a rising population the demand for tomato and its products in the country is expanding at a very high rate of 7.3% per annum, much higher than the increase in its domestic production causing a ballooning tomato trade deficit.

“The country fails to play a significant role in international export markets, and benefit from a fast increasing export of fresh tomato and its products. Pakistan earns only 28% of the world average export price suggesting great challenges in improving the tomato value chain. The country can export less than 1% of its production while the world average export-production ratio is 4.7%. Pakistan has great potential to improve its export-production ratio because of its lower farm gate prices than the world average,” it reads.

The fate of the tomato

Pakistan’s current state of tomato production is better than what it was two decades ago. Tomato production has risen since the early 2000s. In fact, in 1980 the total area under cultivation for tomatoes was less than 30,000 hectares. This rose steadily over the 1980s to get to just underneath 50,000 hectares under cultivation in 1990. The real era for growth for the tomato crop in the country came between 1996 to around 2005. From 1995-99 the area growing tomatoes grew by 20,000 hectares to reach around 70,000 hectares under cultivation.

However, this rise was not because of any particular strategy. The demand for tomatoes was rising in Pakistan, and that meant more area was coming under cultivation. In the early days, some government attention was paid to the crop with new seed varieties being introduced and incentives given.

Area under tomato in Pakistan has more than doubled in Pakistan from 29.4 thousand hectare in 1995 to 61.9 million ha in 2016 with an annual growth rate of 4.9%. Similarly, production has also increased from 294.1 thousand tonnes to 587.1 thousand tonnes during the corresponding year producing an average annual growth of 4.4%. All of the increase in tomato production in the country came from area expansion, without any improvement in per hectare yield.

However, largely the demand continued to outrun the increase in production and because there was very little to be done in the way of improving cultivation techniques the tomatoes continued to languish and Pakistan’ reliance on imported tomatoes continued. With imports from India banned in recent years, Iran and Afghanistan have not quite been able to fill the gap.

In this time, great potential has been seen in Sindh and Balochistan. Sindh has emerged as the highest tomato producing province with tomato grown on an area of 27.9 thousand ha followed by Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), Balochistan and Punjab provinces respectively. The climatic and soil condition of Sindh province is favourable for successful cultivation of Tomato. The total share of Sindh province for tomato area is 43.6 percent. Balochistan is also a leading tomato producing province and has big potential for tomato production as it occupies 20.8% of tomato area and 24.6% of production in the country, according to the planning commission report.

What needs to be done?

There have been some encouraging signs. Tomato production in Pakistan has picked up significantly since the turn of the century, doubling over a ten year period, but much needs to be done before tomatoes are sustainable. For this, the most important factor will be making sure we get the most yield per area possible.

Tomatoes are grown all year around in Pakistan. For most, seeds are grown in nurseries and then supplanted into farms where they grow and increase in yield. There are also other popular methods of growing tomatoes, particularly via tunnel farming. Majority of farmers used to raise a nursery and then after 30 -40 days they transplant tomato seedlings in the field. For nursery raising 100 – 125 g/acre tomato seed is required. However, all of this requires significant time, investment, and know-how. For the average tomato farm, much assistance is required.

A program of variety development suited to the local environment is necessary along with the establishment of a Tomato Research Stations need to be established in cluster areas in Sindh, Balochistan, and KP which can work under the main National Tomato Research Institute in Sindh for development of Tomato hybrid and open pollinated varieties. The recommendations of the planning commission also ad the establishment of certified tomato nurseries for healthy seedlings, promotion of good agronomic practices, publishing technical guidelines, managing and certification of modern tomato fields and tomato puree plants to meet the quality fresh tomato and its product demand in local and export markets, and establishment of cold storages, and pack houses by the FEG all among the steps that need to be taken if anything is to become of our tomatoes.

At times in this series where we intend to discuss different crops and their status in Pakistan, the talking points will seem repetitive. On other occasions, they will seem radically different. However, in each case they are recommendations that need to be repeated ad nauseum largely because the entire agricultural infrastructure in the country faces a host of common problems that have similar solutions. More research, more money, more assistance will all lead to our food security issues improving.

I’m truly impressed with your blog article, such extraordinary and valuable data you referenced here.

사설 카지노

j9korea.com

Dear Happy to see your article on tomato, but when i reach on the data and recommendations, that i found the same data you had copy and past from my study “Cluster development based agriculture transformation plan vision 2025”. This study was carried by CABI under planning commission of Pakistan.

Any way weldon