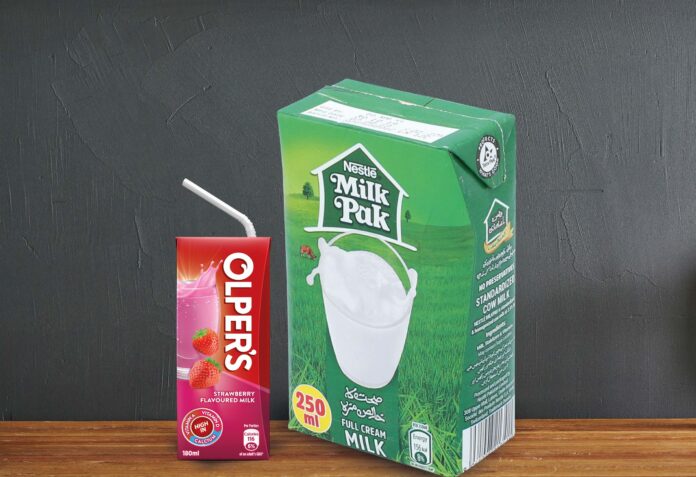

Engro-FrieslandCampina, henceforth referred to as Friesland for the sake of brevity, has had a good year. The dairy titan finally surpassed the Rs 60 billion threshold in terms of sales and its flagship brand, Olpers, has come neck and neck with Pakistan’s largest milk brand — Nestle’s Milkpak.

Normally this would be cause for celebration for any company. And while the good people over at Friesland will be happy with their recent performance, the mood at HQ might be slightly sombre. Despite surpassing the Rs 60 billion mark and firmly being in second place in the country’s market for dairy and its alternatives, Friesland is far behind its closest competitor. In the world of dairy Nestle is King and with sales worth over Rs 120 billion there is a lot of catching up left for Friesland to do.

So what is with the disparity? The story of packaged milk in the country and how the dairy industry has evolved in Pakistan is well recorded. It has been chronicled in quite some depth by this publication as well. Very briefly put, Engro and Nestle have had their horns locked in a battle for supremacy.

Read More: The next phase of the Milk Wars

But over time Nestle has come out on top simply off the back of their very diverse product range. While Nestle’s Milkpak and Friesland’s Olpers may be at par in terms of sales, Nestle simply makes far more things and is twice the size of Friesland. Besides their dairy division, Nestle has also diversified far beyond just dairy products with their juices and other food products. Meanwhile in their attempt to bolster Olpers, Friesland may just have hit the maximum sales capacity of its flagship Olper’s brand.

The twist in the tale is that Nestle remains unperturbed. Nestle’s sales are bolstered by a product portfolio as expansive as one could fathom. Amidst this backdrop, one might anticipate Friesland to introduce a plethora of products ranging from infant formula to juices in an attempt to bridge this gap. However, none of this appears to be on the horizon.

Instead they have decided to pick a different segment within the milk market to dominate: flavoured milk. And they are trying to conquer it with a strategy that is not new but has fallen out of use in recent times: Cartoons.

Enter flavoured milk

At first blush, this decision may seem innocuous. Yet, this is not Olper’s maiden voyage into the realm of flavoured milk. The company discontinued the product in 2014. Its resurrection in 2020 should have raised eyebrows, but it slipped under the radar. At that juncture, it was unclear whether it was here for the long haul or not. With a dedicated cartoon in its arsenal, it is clear that Friesland is doubling down on this venture. While it may initially appear that Friesland aims to monopolise the flavoured milk market to bolster its sales figures, there may be a more nuanced strategy at play.

What are we insinuating? Friesland has sent Olper’s into battle. Almost a decade after the initial iteration of Olper’s flavoured milk fizzled out, Friesland has armed it with the vibrant hues of happy subha. By bestowing upon it a cartoon of its own, it has tasked it with capturing market share from segments where the dairy behemoth has no foothold.

The crux of the matter is that Friesland needs its flavoured milk to infiltrate markets and augment its sales figures without taking the risk of deviating from its core competencies in order to keep pace with Nestle.

Friesland’s not so happy subha

But there is a problem. Nestlé’s dairy division is a behemoth, twice the size of Friesland. This has been the status quo for over a decade, with Nestlé even ballooning to thrice the size in parts of the previous decade.

However, this dominance of Nestlé masks a crucial detail. Nestlé simply manufactures a broader range of products than Olper’s, thereby granting it an overarching supremacy in Pakistan’s dairy and alternatives sector. It boasts a commanding lead of 35%, dwarfing Friesland’s 18%.

However, this dominance of Nestlé masks a crucial detail. Nestlé simply manufactures a broader range of products than Olper’s, thereby granting it an overarching supremacy in Pakistan’s dairy and alternatives sector. It boasts a commanding lead of 35%, dwarfing Friesland’s 18%.

The disparity is most conspicuous when examining the brand-wise split of the dairy and alternatives sector. Friesland’s Olper’s, Tarang, and Dairy Omung all trail their Nestle counterparts by a hair’s breadth. However, when you incorporate Nestle’s other products such as baby formula into the equation, its competition becomes non-existent.

The most straightforward strategy for Friesland would be to introduce infant products. It does have infant centric products in its global lineup but the local market is stringently regulated. Advertisements are heavily controlled. It necessitates direct selling to doctors — almost akin to the pharmaceutical industry.

This means that it would take Friesland years, even decades to catch up with Nestle, if they were to tread into the formula milk category in Pakistan to bridge the proverbial gap.

So, why has flavoured milk of all things become Friesland’s pièce de résistance?

Choosing your champion

In the grand scheme of things, the flavoured milk sector may not be the most expansive arena for a company to stake its claim. Friesland’s estimation places the category at a modest 60-65 million litres annually, a mere drop in the ocean when juxtaposed with the behemoth that is the fruit drinks sector — a market tenfold in size according to Friesland.

The competition, however, is fierce even within this niche. Brands such as Dayfresh, Pakola, Shakarganj, and Nestle’s renowned Milo are but a few of the contenders. Intriguingly, Olper’s has consciously chosen not to vie for dominance within the flavoured milk market.

“Rather than targeting market share gains within the existing, rather small, flavoured milk market, our ambition is to accelerate the growth of the category,” elucidates Faisal Amanat Khan, General Manager of Marketing at FrieslandCampina.But who, one might wonder, is Olper’s zeroing in on? Juices? Sodas?

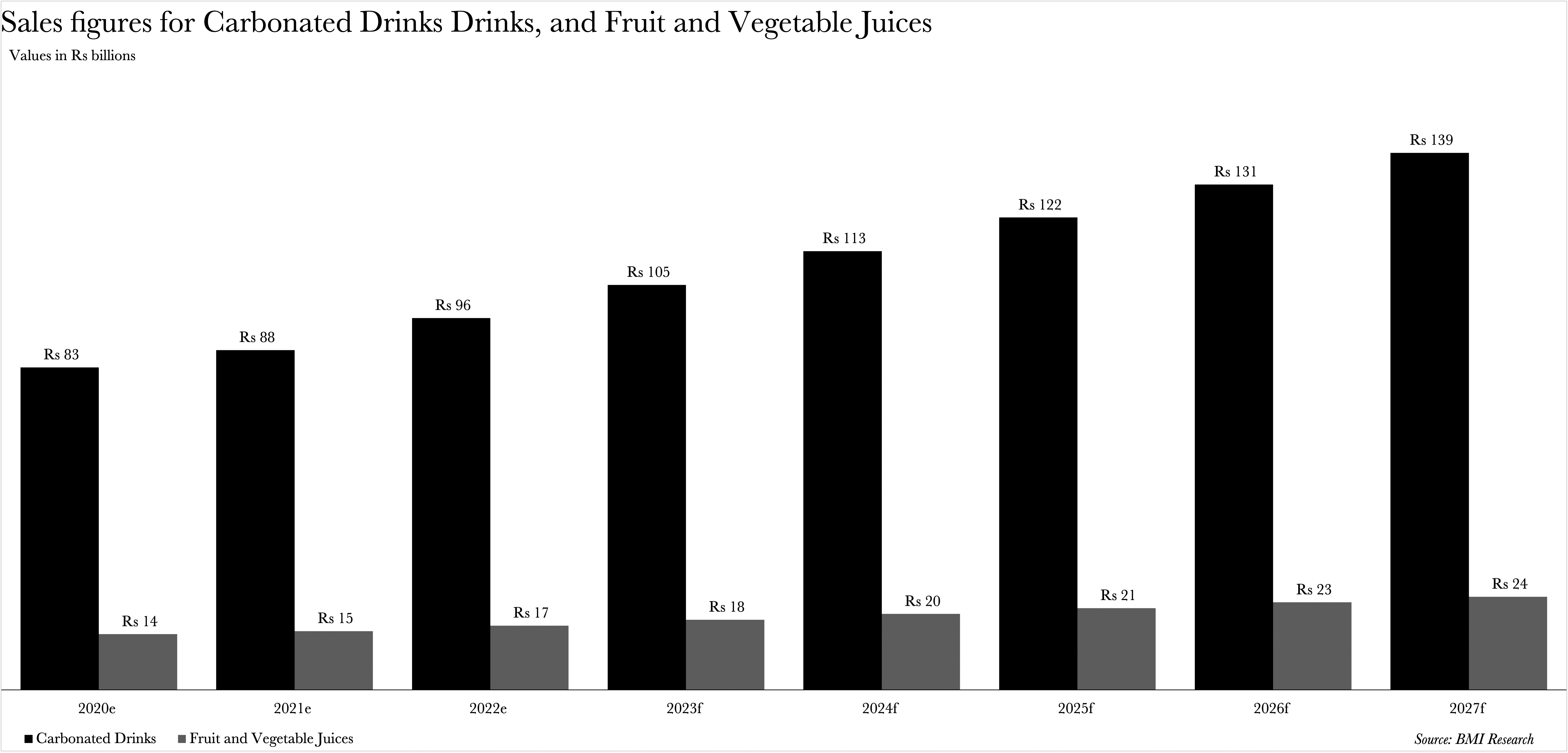

Assuming they were, it wouldn’t be a bad idea in all honesty. Whilst neither of the two aforementioned categories match dairy sales in any capacity, the two are sizeable on their own. Carbonated drinks are set to clock in sales of Rs 105 billion in 2023, whilst fruit juices will be hitting Rs 18 billion. Both are also poised to grow at compound annualised growth rates (CAGR) of 7% till 2027 to hit sales volumes of Rs 139 billion and Rs 24 billion respectively.

Slices of either wouldn’t be the worst thing to happen to Olper’s, but could a cartoon of all things help them if they were to choose to go down that route?

Slices of either wouldn’t be the worst thing to happen to Olper’s, but could a cartoon of all things help them if they were to choose to go down that route?

The cartoon at hand

First things first, why is there a cartoon? Well this isn’t exactly a new strategy. Cartoons have been used to promote products before in this country as well. Perhaps the first to do it and do it successfully was Safeguard soap’s Commander Safeguard which became not just a good method of advertising but also proved to be a popular show that is still a cultural reference point from the pre-cable era. Caltex during its brief stay in Pakistan promoted itself through a comic book about cricket called Supa Tigers and Tetra Pak also introduced Tetrapak Milkateers which proved less popular than Commander Safeguard despite having a higher budget. Remember, these are not cartoonish mascots that many products have but actual cartoon productions meant to be aired. The goal is to get kids interested in the show so that they then want to buy the product. It might seem silly but it works.

“About a year and a half ago, we engaged in research to understand the reasons behind the category’s limited growth. It concluded that this is due to the fact that it is not tethered to a consumption occasion,” Khan explains. “Association with a relevant consumption occasion helps brands and categories become more relevant to consumers by naturally fitting into their existing habits,” Khan expands.

The occasion that cartoon is aiming to become synonymous with? Children’s lunchboxes. There’s a general focus on children’s health altogether, with Olper’s being in more than one place but the flavoured milk looks to have taken aim at children’s lunchboxes.

So, how does Friesland aim to make Olper’s a more prevalent category in the lunchboxes?

Intriguingly, Olper’s stands firm in its resolve not to indulge in comparative advertising that nudges customers to favour their product over another brand or an alternative product. However, advertising can be more sophisticated than just attacking your competitor outright.

Let’s look at a fun fact.

Contrary to popular belief, Milo is not a flavoured milk — it’s a malt. Does this distinction matter? Well, yes and no. Loyal consumers of Milo will continue their consumption regardless. However, Olper’s is on a quest to champion health and one cannot help but wonder when questions about the nutritional value of Olpers’ competitors are brought into question by those who watch the cartoon?

Friesland also doesn’t have anything in its Olper’s portfolio at least that could be termed unhealthy, and subsequently eulogising health through the cartoon won’t lead to flavoured milk cannibalising any of Olper’s existing sales. In short, Olper’s can, and might, have a field day promoting health. What does that mean for it’s not so nutritional competitors? Well, that’s their headache for all Friesland might care.

“With the growing discouragement towards juices due to heightened awareness levels, the brand is strategically leveraging the health and energy benefits of milk (think Milo), specifically targeting children,” explains Emaad Ishaq Khan, Executive Director at Synergy Dentsu & Synite Digital.

“The cartoon is ingeniously designed for children to recall and accept the flavoured milk. It aims to foster recognition and comfort so they don’t reject it. It also aids in weaving relevant narratives and forging a strong association with the children. This makes it easier for mothers to offer it to their children with the reassurance that it’s a healthier alternative,” Ishaq Khan elaborates.

The reality is that lunchboxes do not operate within intricate dynamics. In the absence of an expansion in the average physical size of a child’s lunchbox or a surge in the parent’s income, curating a child’s lunchbox inevitably morphs into an exercise in prioritising certain products over others.

What could possibly be a more effective way to assist mothers in this lunchbox conundrum than by relentlessly emphasising the paramount importance of nutrition? There’s no necessity to explicitly declare that other products are nutritionally inferior to yours; however, accentuating the benefits of a healthy lifestyle for a child while simultaneously emphasising that your product is healthy does seem like subtle competition cloaked in health benefits.

How well would the cartoon do?

“In Pakistan, you’ll see when companies are trying to market to kids, the easier thing they see is, you know, to sort of build up a cartoon in it. You’ll see lots and lots of bigger brands playing with cartoons,” explains Arfa Syed, Senior Vice President at OULA.

Animated mascots such as Knorr’s vivacious spices, Tetra Pak’s Milkateers, and Bisconni’s Coco and Mo, all leap to the forefront of our minds. Yet as we’ve mentioned earlier with the exception of the Mikateers these are all mascots not actual productions. Only P&G’s Commander Safeguard achieved that status. And the success of that show was based on making a quality product that the target demographic would be interested in.

“The heart of the matter is that even when we dare to delve into the world of cartoons, we do so in a somewhat lacklustre fashion. They’re typically 2D characters. We don’t invest adequately in the brand. You can’t advertise enough for a cartoon to seep into mainstream consciousness. Then your entire existence is precariously balanced on the television commercial (TVC), and that TVC is also rather diminutive,” Syed expounds.

It goes without saying that a cartoon confined solely to YouTube will face an uphill battle. Especially if your target audience has the option to watch Cocomelon of all things, and is being incessantly targeted by YouTube’s algorithms.

That’s not to dismiss the potential for children’s cartoons. “There are Hindi dubbed cartoons that mothers may not necessarily want their children to watch, and then there are English cartoons whose storylines may or may not resonate culturally with us,” elucidates Syed. “There’s a significant opportunity to do cartoons right if you’re incorporating local context and languages,” Syed adds.

However, it’s not as if Friesland is oblivious to all this. Khan provides a detailed explanation, “If we just host it on social media, only a few consumers might end up watching it as most digital tools will serve other international content to the audiences” he begins. “We drove initial awareness through a digital reach and advertising plan.”

“We used 15 and 30 second trailers. The audience would simply click on the trailers and be redirected to Olper’s flavoured milk’s social media page where they could watch it,” Khan articulates FrieslandCampina’s digital advertising strategy.

The cartoon makes perfect sense when viewed through a wider lens. Looking at Olpers’ portfolio from a panoramic perspective, they’re emphasising the benefits of breakfast and healthy living in general. A part of a child’s breakfast routine inevitably involves deciding what will go into their lunchbox for school.

Now, one might think that we’re reading too much into this. Perhaps we are, but that doesn’t mean the creators of the cartoon don’t comprehend portfolio strategy.

Want an example of all this? Look at the discontinued box of Olper’s flavoured milk, and the current one. One is clearly more in tune with the conventional milk brand than the other. In its defence, the discontinued one might even look more fun but that’s not how Olper’s is going to be able to take a shot at their only real competitor.

Let’s tie everything back together. At the time of penning this piece, only a single episode of the cartoon has been released. Consequently, it would be premature to pass judgement on the potential success or failure of the series. The cartoon itself, however, is arguably the least captivating aspect of this entire thing. Instead, it’s the myriad opportunities it presents for Olpers’ that truly pique one’s interest.

We’ve previously established that our investigation involved scrutinising the cartoon, and we’ve underscored the fact that flavoured milk isn’t the sole product from Olper’s featured in the animation. This is crucial, as it ties into our discussion on synergies. That was merely the inaugural episode. For all we can predict, subsequent episodes may spotlight Olper’s cheese or their dairy cream. Friesland has the potential to pepper the entire series with their comprehensive product portfolio, should they choose to do so. They could even leverage it as a launchpad to cultivate the brand equity required to introduce the aforementioned infant products.

Why it makes sense

Consider this: Friesland has a choice. It could just sit back, and do nothing — or it could seize the opportunity, and make history. Friesland’s dairy business has been outshining Nestle’s for the past six years, growing at a CAGR of 9% compared to Nestle’s 6% from 2016 to 2022.

One might contend that this higher CAGR is merely a consequence of Friesland’s lower base in 2016, when it had just stopped being Engro Foods, and that it only regained its previous sales volume the following year. This contention, however, crumbles when we examine the data from 2020 to 2022, when Friesland was back to its normal Rs 40 billion in sales that it saw across the 2010s. During this period, Friesland grew at a staggering CAGR of 28%, almost doubling Nestle’s 15%. The company clearly did not rest on its laurels.

Now, ceteris paribus, Friesland will inevitably overtake Nestle if both companies continue operating in their normal capacities. Based on a simple projection of the two CAGRs from 2016 to 2022, Friesland will eclipse Nestle in 2050, when the company will have a total sales volume of Rs 666 billion compared to Nestle’s Rs 655 billion. If we instead use an exponential growth formula of y =b*m^x for both companies, then the timeline shortens to 2038 as the tipping point for Friesland.

These assumptions, however, are based on historical data, and disregard the likelihood that Nestle will fight back. That would be uncharacteristic of a company that managed to create that Rs 60 billion gap in the first place. Assuming then, that Nestle does not do anything at all to challenge the status quo, does Friesland want to wait for two to three decades until it can finally claim the dairy crown? Or does it want to start shrinking that gap as soon as possible?

Why doesn’t anybody want to come into truly healthy ,fruit smoothly segment or the like? Is there not enough profit in it?

Thank you for this great story.