The swathes of lush green fields of the Mitchell’s Fruit Farm in Renala Khurd Okara only occasionally come into the full public view when the local member of the provincial assembly (MPA), Jugnu Mohsin, is visiting her constituency. In Okara, the people know her as the daughter of S M Mohsin, who has run the show at the Mitchell’s Fruit Farm for more than half a century.

For the residents of Renala Khurd and its adjoining areas, 720 acres of oasis that makes up the Mitchell’s Fruit Farm is much of all they know. S M Mohsin, the owner and head of the company for more than half its existence, is from the family of the Pir of Shergarh, a large landowning family whose home is located some 10 miles from Renala Khurd.

So when Jugnu Mohsin visits the farms, it is a mix of political and feudal patronage that turns the occasion into a festive one. Large tapeball cricket tournaments are arranged on farm grounds, mass dinners undertaken, and gatherings to hear the woes of area locals organised.

The Mohsins, consisting of patriarch S M Mohsin, along with wife Sitwat, son Mehdi Mohsin and daughter Jugnu Mohsin, find themselves irreplaceable if slightly aloof members of the community that is dependent on the economy that surrounds Mitchell’s. In Lahore, the family paints a very different picture. Erudite socialites who form a permanent fixture of the city’s social and economic elite, for most of 2020, the Mohsins have been looking for a buyer to take Mitchell’s off their hands.

The search to find a buyer has ironically been a fruitless endeavour. After all, the reason they have wanted to sell has been that Mitchell’s has been doing abysmally in recent years, and everything points to bad management as the reason. But after a string of family entanglements and squabbles, Mitchell’s is off the market, with Jugnu Mohsin and her husband Najam Sethi taking over management from S M Mohsin and Mehdi Mohsin in a bid to revive the glories of old that Mitchell’s has seen.

But with the new management has also come a change in culture. Once shrouded in secrecy, a new CEO has meant Mitchell’s currently seems an organisation much more welcoming to the media. Yet the chinks in the company’s armour that have led Mitchell’s to where it is now are still very much alive, and already resulting in snide slights that could possibly devolve into all out chaos.

Is the new Najam Sethi-led Mitchell’s a last ditch effort? The final, desperate, throes of a sinking ship? And if so, what plan is Sethi and his trusted CEO, the newly appointed Naila Bhatti, bringing with them to take Mitchell’s back to the top?

A history of substance and family

Proudly packaged on all their jams, jellies, chocolates and toffee packets is the number ‘1933.’ That is the year that Mitchell’s was founded by Frances J. Mitchell as Indian Mildura Fruit Farms Ltd. Since its initial days as the second innings of Frances Mitchell – he came to India to regain a fortune he had lost – Mitchells grew to be a household name, and a successful company that was the first food production and processing company in Pakistan to get an ISO 9001 accreditation.

But it was in 1958 that a changing of the guard occured. Feeling heat from the Pakistani government to leave, Frances Mitchell’s son accepted an offer to buy the orchards and the company that came from Syed Maratib Ali, the famed businessman who was the largest contractor to the British Indian Army troops in India during World War Two, and the father of Syed Babar Ali.

Syed Maratib Ali had bought the company with the intention of settling his son-in-law, S M Mohsin, who had just married Maratib’s youngest daughter two years earlier. From this point on, S M Mohsin would have complete control over the orchards and the Mitchell’s brand. Mohsin got off to a shaky start, making less than wise bids in his initial years.

The way fruit farming works is that most of the produce from an orchard is auctioned off annually, with only enough retained for what was needed to produce any jams or other fruit products a farm might be making. A couple of bad lots that had been leased meant that Mohsin, alone and suddenly the owner of 720 acres of land, had 600 acres of fruit orchard that he needed to do something with. These initial days of toil would come to an end soon, and Mohsin’s land owning roots would come in handy as he continued to keep Mitchell’s on top of the game.

The period that followed was one of growth. In 1980, the company diversified into confectionery, making sugar candies, milk toffees and chocolate eclairs, which resulted in its annual sales being doubled. In 1993, Mitchell’s became a public limited company in preparation for a public listing on the Karachi Stock Exchange, which it able to achieve through an initial public offering (IPO) that same year in November.

Five years later, in 1998, they became the first food processing company in Pakistan to get ISO 9001 accreditation. In 2001, the company began to produce its own chocolates. But this is where the story starts to get a little less than perfect.

In 1998, just as Mitchell’s was celebrating their ISO accreditation, National Foods launched its range of jams and jellies and got ISO certification. This was the first stiff competition that Mithcell’s had to face on a national scale.

While National has a product line that has some differences with Mitchell’s – National derives a considerable portion of its revenue from spices, a business Mitchell’s is not in – there is considerable overlap in between the two companies’ businesses. Both Mitchell’s and National compete in the jams, jellies, and marmalades business as well as the tomato ketchup business.

As the years passed, National proved to be a wily competitor, spending on advertising and keeping up by changing their packaging and introducing new products. They also launched affiliated products, like instant desserts, that went with their jams and jellies.

On the other end, Mitchell’s under S M Mohsin continued in its ways, still getting a big chunk of business on the basis of the near-century long inertia their company could rely on. In 2007, it became apparent that Mitchell’s would have to do something to keep up, which launched an effort to modernise. By 2008, Mitchell’s would upgrade everything from their wrapping stations to their packaging in both the confectionery and grocery section.

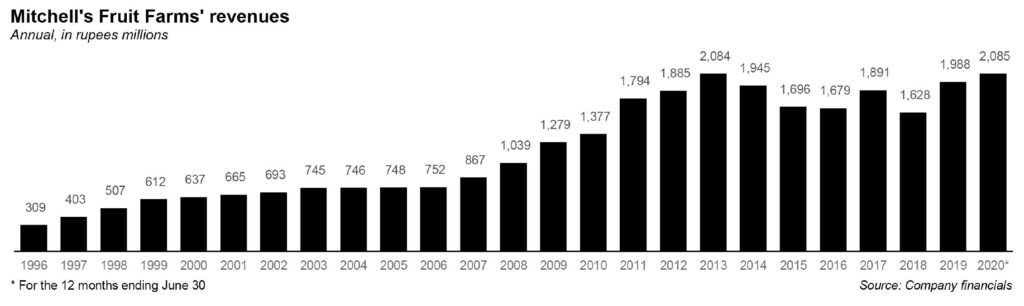

What followed was a relatively strong showing. Between 1996 and 2008, Mitchell’s had grown its revenues from Rs309 million to Rs1,039 million, at an average growth rate of 10.6% per year. Between 2008 and 2013, Mitchell’s grew its revenues even faster, at an average of 14.9% per year, to reach Rs2,084 million by 2013. (Mitchell’s financial year ends September 30.)

That second number sounds like improvement, but in reality, it is not. You see, with a consumer-facing food business, one of the key factors to consider is inflation. Between 1996 and 2008, inflation in Pakistan averaged 7.0% per year, but between 2008 and 2013, it averaged 11.7% per year, which means that the inflation-adjusted growth rate for Mitchell’s revenue actually declined from an average of 3.4% per year prior to 2008 to 2.9% per year between 2008 and 2013.

Their aggressive revamping of both their product line and manufacturing capacities, allowing for continued growth in spite of the ailing state of Pakistan’s economy during those years. However, they continued to not spend on marketing as much as the competition was. It is also around the 2007-8 revamp point that the detailed corporate history and timeline that Mitchell’s has on its website goes quiet too.

What happened and who is in charge?

Between the time the company went public and 2007 (close to the end of the Musharraf administration), Mitchell’s was a company that seemed to be plodding along at a reasonably healthy pace: nothing spectacular, but at least somewhat respectable growth. Yet, in hindsight, at a time when the Pakistani middle class was expanding rapidly – and companies that served that middle class were seeing their revenues soaring – it should have been evident that Mitchell’s was missing something big.

In most Pakistani manufacturing companies, when one sees slow revenue growth, the easiest culprit is usually the fact that the ownership and management are not investing sufficiently in capital expenditures to help grow the asset base of the company, which in turn could help grow the business.

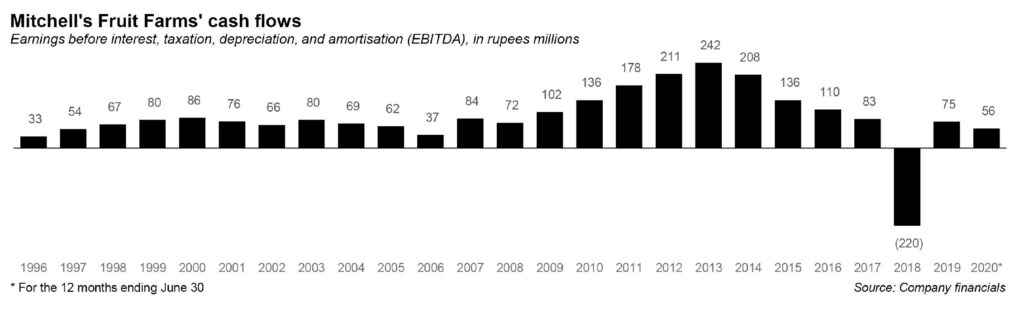

That does not appear to be the case with Mitchell’s. Between 1996 and 2007, the company’s management spent Rs348 million on capital expenditures, which represented 43.7% of the company’s earnings before interest, taxation, depreciation, and amortisation (EBITDA), a measure of the company’s free cash flow. That is not particularly high, but it is also not very low either.

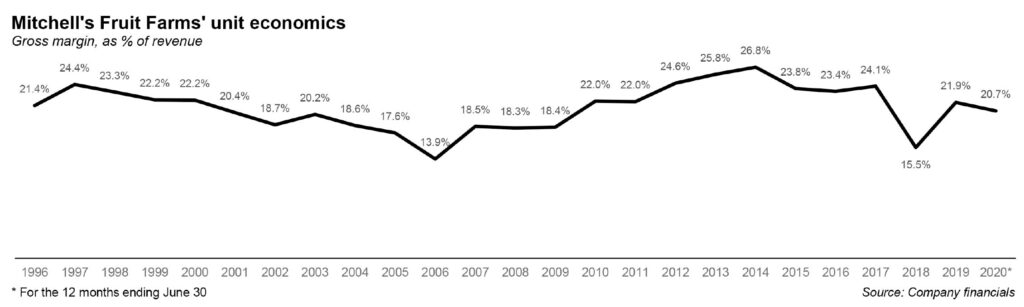

A clue as to what went wrong for the company appears not in how it chose to utilise its cash flows (which is where a lot of other companies go wrong), but in other elements of its business strategy. Specifically, between that period, Mitchells’ gross profit margin hovered between a high of 24.4% in 1997 and a low of 13.9% in 2006, with considerable variation in between.

That number is considerably lower than other similar businesses, which tend to have gross margins north of 30% and may reflect the fact that the company does not feel it has significant pricing power for its products and has to sell them at a lower price, or that its manufacturing operations are not as efficient as those of its competitors, meaning its per unit cost is too high.

As Profit points out in the box accompanying this story, on a per-gram basis, Mitchells’ product prices are higher than those of National in product lines that the two companies directly compete in, a reflection of the fact that Mitchell’s is likely seen as a somewhat higher quality brand.

But if Mitchell’s is able to command higher prices, why are its margins lower than those of National, which has had margins in the 32-34% range over the past five years, a time when Mitchells’ margins have not improved beyond that 20-25% range it has historically been in.

Around 2008, the Mitchell’s management decided that they needed to invest heavily in improving the quality of their operations and pump up their attempts at improving the company’s product distribution strategy.

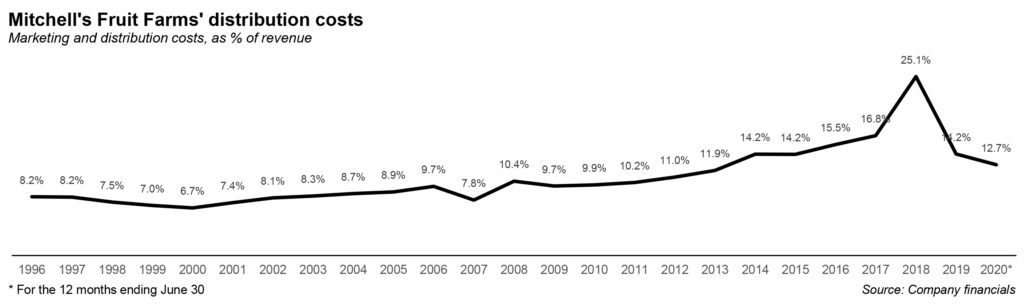

The problem, however, appears to have been a misallocation of resources. Capital expenditures as a percentage of EBITDA did not rise (and, in fact, declined to an average of 35.7% per year) between 2008 and 2013, meaning the company did not materially invest in improving its business operations. What it did do, however, was dramatically increase the incentives it offered distributors to push its product, taking its total marketing and distribution costs from 7.8% of revenues in 2007 to 14.2% of revenues by 2014.

This seemed to be a huge strategic mistake that the management took far too long to catch. During that seven-year period, distribution costs rose at an average of 22.4% per year, even as revenue grew by only 12.2% per year during that same period. Inflation averaged 11.9% during this period, meaning that the company was effectively not growing its topline in inflation-adjusted terms.

All it was doing was lining the pockets of its distributors with incentives that were yielding no tangible benefits for the company in terms of increased sales.

This point is explicitly acknowledged by the company’s management. “Three reasons for this [abysmal historical performance]: lack of adequate sponsor oversight of management; misplaced marketing and distribution strategies; no significant ad spend,” said the company’s spokesperson who declined to be identified by name.

Mitchell’s also clearly did not understand its changing market landscape. Bakeries, for example, began producing their own jams, jellies, and squashes, and refused shelf space to Mitchell’s. And because they barely spent any more on advertising, customers did not ask for Mitchell’s and were more than happy try alternatives.

There is also the fact that, in substantial parts of Pakistan, grocery stores do not have aisles that customers can walk down, but instead have counters at which customers have to ask for specific products by name, which means that if customers do not have a brand’s name top of mind, they will not ask for it and instead may end up purchasing the product of a competitor.

Despite the revamp attempt in 2008, business has not improved for Mitchell’s. Between 2008 and 2013, revenue growth did accelerate somewhat, but that appears to be mostly driven just by consumer price inflation. And the company has stagnated between 2013 and 2020, with revenue growth actually equal to 0% per year during that time.

Since 2016, Mitchell’s has lost money every single year, losing a combined Rs513 million during that period. Those losses have resulted in rising indebtedness for the company. As recently as 2013, the company had just Rs97 million in debt. As of June 30, 2020 – the latest period for which financial data is available – the company has Rs805 million in debt, of which Rs150 million was pumped in by the Mohsin family. That indicates that the company is having trouble raising money from traditional bank loans.

The company being in loss for a few years meant that tensions within the Mohsin family began to run high, as disagreements over how the company was being run and who was to blame for the failure started becoming public knowledge.

A number of management changes were attempted in this time. Mujeeb Rashid, a company stalwart with over 45 years of experience in leading multinational companies in Pakistan, was the CEO when Mitchell’s had its growth run from 2009-16. But declining profits going towards definite losses in 2015 and 2016 meant that he was removed in favour of Muhammad Zahir, the former director of marketing and sales at the Fatima Group.

Zahir only had a short run as CEO, between May 2016 and September 2018. Meanwhile, the company reported another loss of Rs30.8 million in 2017, and then another loss of Rs292 million in 2018. At this point, the discontent within the family was high, with Jugnu Mohsin and the sisters complaining that their brother, Mehdi Mohsin, was running the company into the ground. Selling Mitchell’s seemed the logical option.

The attempted sale

By the middle of 2018, it had become clear to the Mohsin family that they were not having much luck in turning around Mitchell’s. They then decided to pursue a sale of the company and, according to sources familiar with the matter, hired Habib Bank Ltd to be the sell-side investment bankers to manage the process of finding suitable buyers and hopefully even succeeding in getting a bidding war going over the company, which might raise the price the Mohsin family could get for the company.

At the time the family first broached the subject of a sale, the company’s market capitalisation – the total value of the company – was hovering around Rs2 billion, based on its share price on the Pakistan Stock Exchange. If the Mohsin family were able to sell at close to that price, they would net over Rs1.2 billion for their shares in the business.

By July 2019, Mitchell’s began talks with Bioexyte Foods – the food company owned by the conglomerate that also owns Getz Pharmaceuticals – to sell 51% of its shares, or nearly the entirety of the shares currently held by the Mohsin family. Both companies are majority-owned by Khalid Mahmood, who has been running the Karachi-based Getz Pharmaceuticals since 1996. Getz is one of Pakistan’s largest generic pharmaceuticals manufacturer, and Mahmood has used the cash flows from that core business to expand into several other business lines, including the foods business.

(It is unclear if Habib Bank Ltd was still acting at the company’s sell-side investment bankers at this point, and whether it was HBL’s bankers that made the introduction in the first place.)

The move to sell Mitchell’s to Bioexyte seemed to be the end of the line for the storied company, and talks entered final stages in early 2020, around the time that the coronavirus pandemic hit Pakistan. Right near the end, however, according to a Mitchell’s spokesperson, the talks fell through with no hopes of a renegotiation.

The statement from the spokesperson said that the “gap between Bioexyte and Mitchell’s Fruit Farms was too big to bridge.” According to sources familiar with the matter, the ‘gap’ was most likely referring to the 40% reduction that Bioexyte made in the price they were willing to pay compared to their initial offer to Mitchell’s on account of the economic slump that followed the coronavirus pandemic.

Mitchell’s stock price had soared from a low of Rs195 per share on October 11, 2019 to Rs344.99 per share on January 27, 2020 – a stunning 77% jump in the stock price in just over three months – around the time the transaction was announced.

When it fell through, the stock price tumbled back down again, closing at Rs228.49 per share as of the close of trading on Thursday, September 10, 2020 on the Pakistan Stock Exchange, down 33.7% from its peak earlier this year, but still 17% above the trough of October 2019.

The Najam Sethi takeover

With the sale having fallen through, the frustrations in the Mohsin family began to grow, with Jugnu Mohsin being vocal in how she felt about the way the company was being run. Eventually, the family arrived at an impasse that resulted in S M Mohsin and Mehdi Mohsin stepping down and allowing Jugnu to operate the company, which in practice meant that her husband Najam Sethi was installed as chairman.

Currently, Najam Sethi is the chairman of the board of directors, with S M Mohsin becoming a non-executive director, Mehdi Mohsin an executive director, and Sitwar Mohsin also a non-executive director. Mehdi Mohsin’s position within the management of the company is not defined anywhere on the company’s website or its financial statements. He is not its CEO, CFO, or Company Secretary, all of which are positions held by non-family professionals.

While the Mohsins have stayed on the board, Sethi is now the one running the show, and his plan appears to be having a hands-on approach as chairman if he is going to turn the company around.

To achieve this goal, Sethi has brought on Naila Bhatti as the company’s CEO, his tried and tested executive both from his days serving as Chairman of the Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB) and his time spent with the media and financial conglomerate owned by the family of former Punjab Governor Salman Taseer.

Naila Bhatti’s mission is simple enough, to stop the rot at Mitchell’s and make it profitable again. How will she do that? The plan for that has yet to be made public despite the company’s recent openness to speaking with financial journalists. (That openness may be because of Sethi, who is first and foremost a newspaper editor himself.)

When it comes to diagnosing the problem, Sethi, Bhatti, and their team appear to be quite clear about what they think caused the problem: “Over time, the management had become flabby and uncoordinated,” said the company’s spokesperson. All of these problems can be traced back to the previous management, meaning S M Mohsin and Mehdi Mohsin.

It is fair enough for this fresh management to put some of the burden of failure onto the previous management, but one wonders how much of this is genuine and how much of the willingness to say it in so many words comes from family dynamics. What is clear is that no matter why they are saying this, Sethi has identified the problems facing Mitchell’s, and Bhatti has a long, difficult task if she is to try and fix them.

Since 2018, the company’s losses have narrowed somewhat, from the peak of Rs293 million in 2018 to Rs80 million in 2019. Management attributed that decline in losses to “two reasons: a rectification of costly distribution errors, and an increased B2B business.”

The numbers back up that story: distribution costs as a percentage of revenue declined from the 2018 peak of 25.1% down to 14.1% of revenues in 2019, while revenues grew by 22.1% during that year. And distribution costs have continued to come down in 2020, down to 12.7% of revenue for the nine months ending June 30, even as revenue growth has slowed to just 4.9% during that same period.

So what is Najam Sethi’s plan for the company’s future? Raising capital and bringing in a new team, it seems.

“The sponsors are planning an equity rights’ issue to raise money in the next three months while keeping their majority shareholding intact, i.e. underwriting it themselves,” said the spokesperson. “A new professional management has come in to make a dynamic five-year business plan. The sponsors are getting directly involved in overseeing this process. “The company is planning to enter a new era viewing its past losses and new challenges.”

Raising capital through equity when the company’s debt lines appear on the verge of exhaustion – and when the debt to equity ratio has climbed to over 10:1 – seems like a prudent move. But Mitchell’s problem was never a lack of money: it was bad decisions on where to spend it.

In selecting a marketing executive to run the whole company, Sethi is sending a clear signal about what that money will be spent on: consumer-facing marketing, and perhaps some business-to-business marketing as well. But will that be enough to help Mitchell’s catch up to competitors like National, who are now far ahead in terms of size and market share?

It seems unlikely that marketing investments alone will do the trick: the company will need to expand its manufacturing operations to match the scale its competitors now enjoy if it is going to catch up to them in terms of its margins. The silence on that front from the new management should be disconcerting to investors who were hoping to see Mitchell’s undergo a true turnaround.

An excellent, well researched and informative article on what I consider a Pakistani institution. Well done to the writer. Mitchell’s problem is 3 fold: Operations (including product), route to market, and marketing. Hope Mitchells makes it.

Nice article , Weakness may convert in opportunity , if consistency there!, A strong competition, category’s grow….

There’s much to be learned from SHAN’s success of targeting Pakistani diaspora, particularly in the USA!

Nice analysis. But the price comparison chart of Mitchell’s and National used by writer was like comparing apples to oranges. Use comparison of same product prices to augment your article. Currently, Mitchell’s is selling it’s products at comparitively less price than its compatitors.

Mitchell’s will survive in sha Allah because of its quality and name ! Therefore improving the quality of products and introducing its name through social media to the young generation will increase its sale.