There has been a major change in Pakistan’s carbonated drinks industry. In the year 2023, Coca-Cola was the most-sold carbonated drink in the country. Just over 451 million litres of Coke were sold in the last calendar year.

This beat out Pepsi, once the biggest carbonated drink in Pakistan, which sold just over 372 million litres in 2023. This is seemingly a major shift in consumer preference. Besides the flagship products, Coca Cola also had the bigger share of the overall carbonated drinks market.

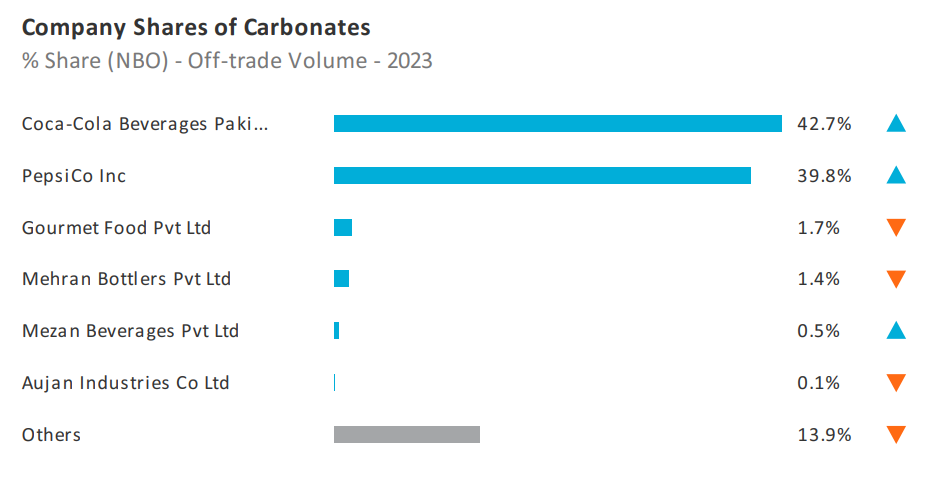

Of the overall 1.33 billion litres of carbonated drinks sold in Pakistan last year, including all of the other brands these two companies operate such as 7Up and Sprite, Coke Pakistan had a market share of 42.7%, while Pepsico was close behind with 39.8%.

But even though Coke Pakistan technically has more sales than Pepsico in the carbonate beverages department, Pepsico is well ahead of Coke off the back of one single product.

Sting.

Pepsico launched the iconic energy drink in Pakistan back in 2010. Since it is considered an energy drink, or a “stimulant drink” as it is legally labelled in Punjab, it falls under a separate category of product entirely. Over the years it has become abundantly clear that Sting’s competition is not Redbull or other canned energy drinks with ginseng (the product present in most energy drinks), but rather Coca Cola and Pepsi.

In the 14 years since it has been around, Sting has become the fourth largest drink in Pakistan after Coca Cola, Pepsi and 7Up. And it is fast catching up with 7Up. This means it sells more than Sprite, Mirinda, Mountain Dew, and Fanta. In fact, according to the sales numbers available for 2023, Sting has sold more litres than Mountain Dew and Fanta combined.

This is all despite the fact that Sting does not (yet) come in packaging of over 500ml. Currently, this 500ml litre bottle of Sting costs Rs 100. Its competitors like Fanta, Mountain Dew, Sprite, 7Up all come in packaging of 1 litre, 1.5 litre, and in some cases even 2.25 litres and are cheaper per litre in larger packaging. These drinks are also more in demand because they are served at weddings, corporate events, and other such gatherings. Sting is not a drink of choice for such occasions.

This presents us with a unique situation. It means Sting, despite billing itself as an energy drink, is directly in competition with carbonated drinks such as Coca Cola and Pepsi. Whatever it may claim, Sting also looks, tastes, and behaves more like a carbonated drink than an energy drink. But food and health authorities treat it as an energy drink, which can often mean regulatory scrutiny. But it seems the marketing benefit of Sting being labelled an energy drink is well worth it to Pepsico. After all, it is keeping them ahead of the competition.

So how do we get to the bottom of the Sting miracle? Easy, we start at the beginning and move on to the numbers.

Fizzy fights

There isn’t really any major competition to Coca Cola and Pepsi. Sure, there are a few anomalies in the world where local brands compete with the two multinationals. In fact, Peru is possibly the only country in the world where a local soda seller, Inca Cola, outsells both Coca Cola and Pepsi. But these are all outliers. Everywhere in the world the market for carbonated drinks is almost evenly split between these two Global Giants.

Pakistan is no exception. Coca Cola first hit the Pakistani market way back in 1953. Pepsi followed not long after. The logic from the global headquarters of both Coke and Pepsico is simple. Since they are each other’s eternal competition, wherever one goes the other follows. Whatever pricing strategy one follows the other copies. However much one spends on marketing, the other tries to one-up. Wherever there is Coca Cola, there must be Pepsi.

And sure, both companies have a whole host of other products too. Mirinda and Fanta in the orange soda category, and Sprite and 7Up in the lemon soda category are the most recognizable brands. But the main event is always between Pepsi and Coca Cola. In Pakistan, Pepsi has almost always had a bit of an edge. Regional preferences within the country have differed for long periods also because of the supply lines that the companies maintain.

Coca Cola has significant presence in Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, while Pepsi has a strong foothold in Sindh, particularly off the back of the success that has been found by their Pakistan Beverages Limited franchise in Karachi. This is because Coca Cola has five out of six of its production facilities in these provinces while the sixth and smallest is in Karachi,Sindh. Pepsico, on the other hand, has significant production facilities in Karachi. As per a report seen by Profit, Pepsico generally partners with one distributor per city, while Coke Pakistan has multiple distribution partners within a city, with areas divided according to sales volume.

The size of the pie and the shape of the slices

So how has this global rivalry played out in Pakistan? According to the latest market data analysis by Euromonitor, there were 1.329 billion litres of carbonated drinks sold in Pakistan in 2023. This includes all products by Coke Pakistan and Pepsico as well as local competitors such as Gourmet Cola, Cola Next, Sufi, and others.

This is actually a rare year in which the overall sales volumes of carbonated drinks have fallen. In 2022, the total sales volume of carbonated drinks was 1.38 billion litres, which indicates a 4% decrease. What is interesting is that carbonated drinks have seen consistently increasing sales volumes (around 18% annually) in at least the last 15 years for which accurate data is available.

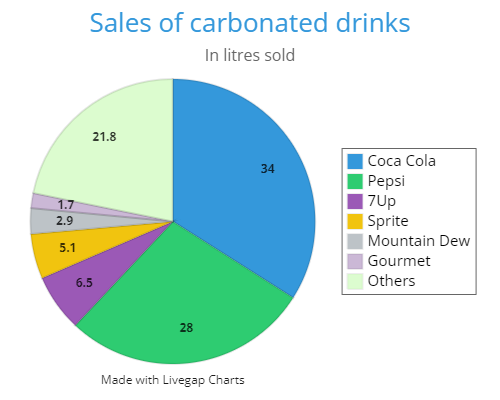

The leading company in this entire mix was Coke Pakistan, which sold nearly 567.5 million litres of carbonated drinks. The biggest component of this was 451 million litres of Coca Cola, which makes up around 80% of the overall sales that Coke Pakistan made in 2023. Of the remaining 20%, over 11% (around 68 million litres) was made up by sales of Sprite, and the remaining 9% was made up of their other products including Mirinda, Coca Cola Light, and Sprite Zero.

Pepsico sold just over 528 million litres of carbonated drink, giving them a total market share of 39.2% compared to Coke’s 42.7%. The breakup of their sales shows that Pepsi was their hottest seller at around 70% of their total sales.Their second biggest seller was 7Up, which sold over 86 million litres making up 16% of their total sales. The remainder of the 14% of sales were made up by Fanta, Mountain Dew, Pepsi Black, and 7Up Sugar Free.

This paints a very interesting picture of the two companies. Coke Pakistan has outdone Pepsico when it comes to selling cola, the flagship product of both companies. But Pepsico has done a better job at selling their other products such as 7Up. This is even though 7Up is sold mostly in 500ml packaging and Sprite dominates the 1.5 litre packaging. Similarly, Pepsico is also ahead of Coke Pakistan in the sale of Fanta, which outsells Mirinda by nearly 25%. On top of this, Pepsico has a more diverse profile of products. One of the reasons for the relative success of the Fanta in 2023 was the decision to reintroduce Fanta’s Red Apple flavour. Coke Pakistan has not introduced any similar products even though there is a market for it as has been proven by Murree Brewery, which has its “Big Apple” as one of its most iconic non-alcoholic products. Pepsico also produces and sells Mountain Dew, for which Coke Pakistan doesn’t offer a clear alternative.

Despite this, as we’ve seen earlier, Coke Pakistan has managed to outsell Pepsico off the back of Coca Cola outperforming Pepsi. Pepsico has managed to close some of this gap through its other products. The percentage gap between the drinks Coca Cola and Pepsi is 6%, but the overall difference in sales for all products is just under 3%.

So how did Coke Pakistan manage to pull this off? For many years Pepsico’s Pepsi was far ahead of Coca Cola. Over the past decade or so, Coke Pakistan has been making a slow but steady comeback. One of the possible reasons is that Coca Cola was not the preferred taste for most consumers. Pepsi has always been known as the sweeter drink. And even though Coca Cola has been preferred more globally, Pakistani preferences leaned towards the sweeter Pepsi. One explanation from insider sources in Pepsico has been that Pakistani tastebuds have become aligned with the global trends. That is why Pepsico has introduced a new combination of Pepsi that they’re marketing as stronger and more fizzy. The new formula was previously being used in the UAE, and Pepsico is trying to fight back against Coca Cola’s encroachment on their once strongly held market.

And while Pepsico is fighting back, there is one difference. On the surface, Coke Pakistan has outsold Pepsico in 2023. But the data we have presented to you is for carbonated drinks in Pakistan. It shows that Coke Pakistan is on top but just barely, and Pepsico has a more diverse portfolio. But this just tells us how these companies are competing with each other in this one category. They have other competing business interests too. For example, Coca Cola sells mineral water under the brand name Dasani and Pepsico sells mineral water under the brand name Aquafina. But in the water segment, their competition is not just each other but other players like Nestle, Sufi, Murree, and Gourmet. Similarly, Pepsico has a very robust snacks segment with their signature Lays brand – something that Coke Pakistan does not have or compete with Pepsico in.

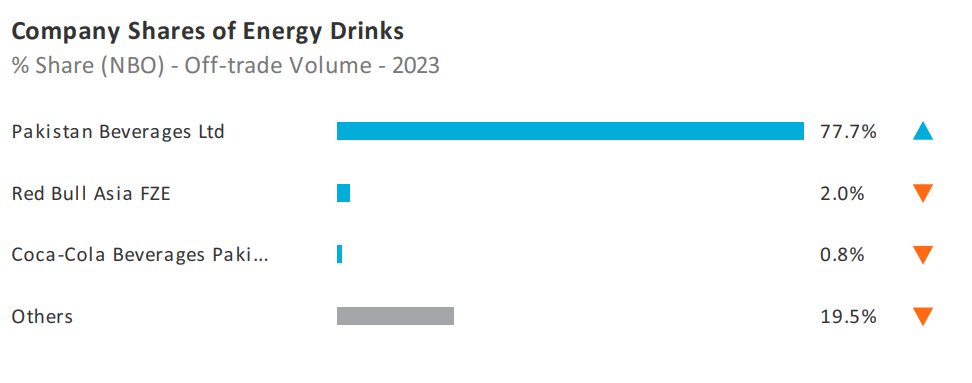

But there is one other segment that is comparable. Not only is this segment one where they are direct competitors, but it is very similar to the carbonated beverages segment. And in this particular segment, Pepsico is ahead of Coke Pakistan. Well ahead actually. So much so that they hold more than three-quarters of the market share while Coke Pakistan is lagging with less than one whole of the market share. The segment is quite small compared to carbonated beverages, but Pepsico’s lead is enough that it tips the overall scales in favour of Pepsico. We would argue that this segment should probably be lumped in together with carbonated beverages in the first place. The sector in question, of course, is energy drinks.

How Sting saved Pepsico’s crown

This is where things get interesting. You see for better or for worse, energy drinks are a separate category in the corporate sector. They are distinct from carbonated drinks. Both products contain many common ingredients. Water, sugar, acidifiers, flavouring, and carbonation exist in both soft drinks and energy drinks. But energy drinks often contain higher quantities of caffeine as well as additional ingredients such as taurine (an amino acid meant to give the body a quick boost) or ginseng (a root indigenous to Asia which reduces fatigue and allows those consuming it to stay alert longer).

It is taurine and ginseng which gives energy drinks their taste. In Pakistan, the concept of energy drinks was not new. Red Bull had been around, at least as an imported product, since the early 2000s. Red Bull officially launched their product in Pakistan in 2001, and much like elsewhere in the world, the concept of energy drinks was synonymous with Red Bull.

Now, Red Bull stood out amongst the existing carbonated drinks options. For starters, it only came in a can. It wasn’t crafted to taste appealing but rather to provide a hit – in a way similar to how coffee is an acquired taste. It was also significantly more expensive, and its marketing promoted the product as an energy boost that could be used by students, professionals, and athletes.

For nearly a decade, this was Pakistan’s only energy drink of any note. That is until 2010, when Pepsico launched a massive campaign for Sting. They billed this new product as an energy drink. But it was very different from Red Bull. For starters, Sting would not come in expensive canned packaging. It would be bottled in 500ml plastic bottles. It was also introduced in a shocking red and gold colour, with flavours called “Berry Blast” and “Gold Rush” (even though they would colloquially come to be known as “red wali aur yellow wali).

Even though Sting was supposed to be an energy drink, it appeared to be more like a new kind of soft drink being introduced by Pepsico. The colours were attractive, and the mass marketing campaign promoted it as a tasty alternative to other energy drinks such as Red Bull. What’s more, it was also significantly cheaper. Pepsico actually marketed Sting brilliantly. They made it into a perfect blend of energy and soft drink. A big part of this was their recipe. Rather than focus on ginseng and taurine, they pumped Sting full of extra sugar as food authority studies would go to show years later. The drink became a staple particularly at khokhas and kiryana stores. The introduction of the glass disposable bottle made it a regular haunt particularly for young boys smoking next to different corner shops. And since it was heavily marketed as an energy drink, it was a cheap alternative to the four times more expensive Red Bull which came in a 350ml can only.

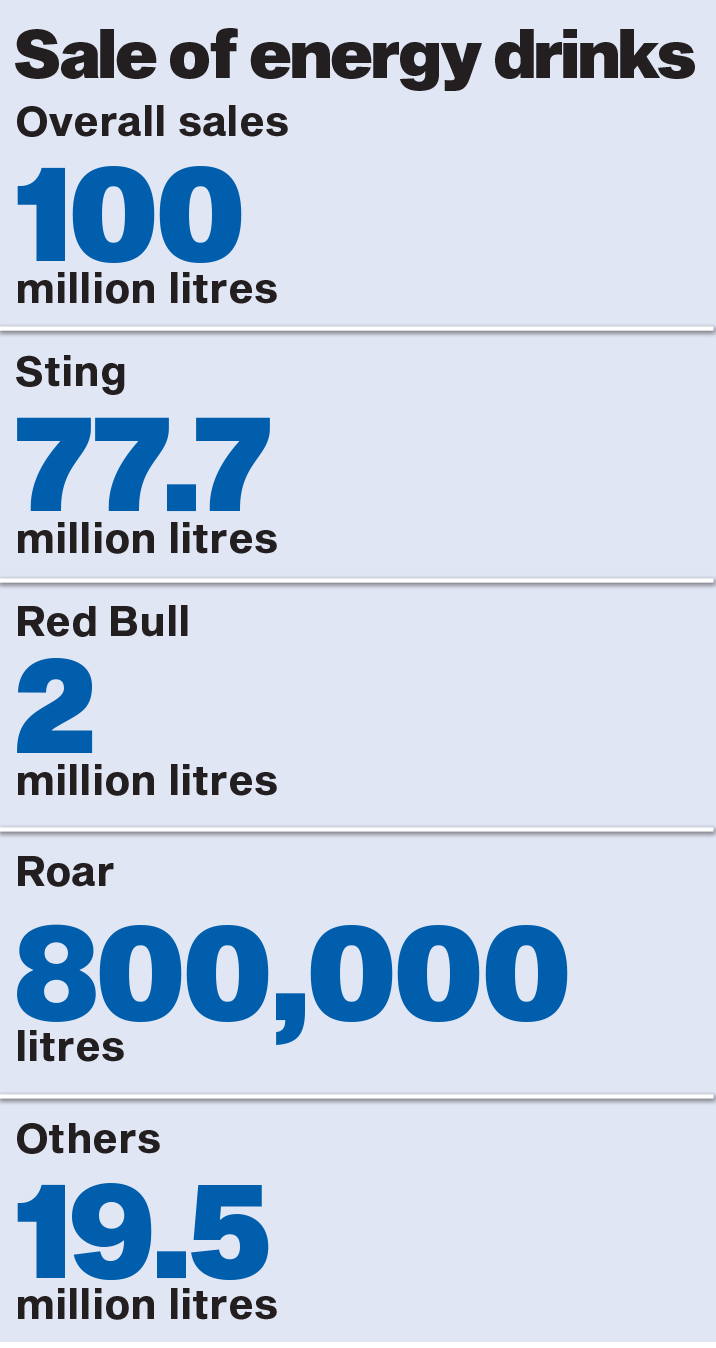

The results are quite obvious. The market for energy drinks is not particularly large in Pakistan. Whereas the total volume of carbonated drinks was 1.32 billion litres in 2023, the total volume of energy drinks sold in the country was around 100 million litres — less than a 10th of the carbonated drinks market. Now, this is a mere 100 million litres. But the difference between Coke Pakistan and Pepsico’s overall sales in 2023 was just under 40 million litres. And by dominating the energy drinks space with what is a glorified carbonated soft drink, Sting has managed to keep Pepsico on top.

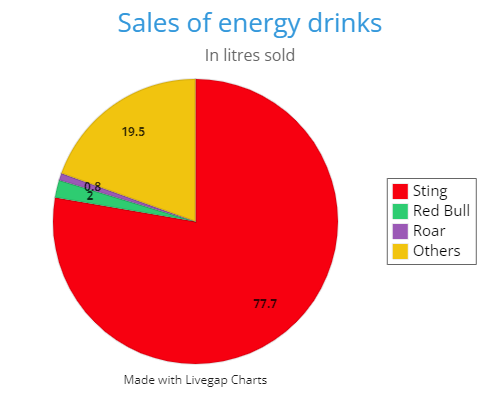

Of the 100 million litres sold, Sting had a massive market share of 77.7 percent, meaning they sold 77.7 million litres of Sting. Coke Pakistan also has a direct stake in all of this. Noticing the massive ground Sting had gained since 2010, Coke introduced Roar in 2019 with a shabang. This was a product like Sting. It was technically an energy drink but didn’t taste like one. But the product was not liked. Most people thought this was Coke’s answer to Mountain Dew, not Sting, and Roar never managed to establish itself as an “energy drink.” As a result their sales have been awfully low. In 2023 they only had 0.8% of the market share, which in turn means they sold only 8 lakh litres of Roar.

Roar also only comes in packaging of 500ml, which means overall they sold around 16 lakh bottles of the drink. Compare this with Sting. Now, Sting comes in three different packings. A 250ml can, a 300 ml bottle, a 500ml bottle, and a disposable glass bottle. We unfortunately do not have the breakdown of which kind of packing sold in what numbers. But the most economical packing is the 500ml original bottle. It is priced at Rs 100 and that gives a per litre cost of Rs 200.

If you assume that only 500ml bottles were sold, it will give us the minimum retail sales figure for Sting in Pakistan. The amount comes out to Rs 15.54 billion. In comparison, the total retail sale figure for Roar all over Pakistan in 2023 was Rs 16 crore. That means Pepsico sold Rs 1,500 crore worth of its energy drinks, while Coke only managed to sell Rs 16 crore. This vast discrepancy means Coke has some serious introspection to do in terms of its Roar product.

Because of this massive gap, if Roar and Sting are counted as carbonated drinks (which they very much also are), then Pepsico’s overall sales surpass Coke. If these two drinks are included, then Pepsico sold 605.7 million litres of their drinks. In comparison, Coke Pakistan only sold 568.4 million litres of their drinks. And if we combine these two markets, that means Pepsico is the overall leader with a 42.3% market share.

Of course, this would add another player in the carbonated beverages market: Red Bull. The iconic energy drink is second on the list of market leaders in the energy drinks segment. However, they are a very, very distant second with a market share of 2%. While that is more than double the market share of Roar, it is still ridiculously less than the hold Sting has on the market. Red Bull, of course, is significantly more expensive. A single can of Red Bull costs nearly Rs 500 and contains 250ml. This means Red Bull has a per litre cost of Rs 2,000. With a 2% market share, Red Bull sold 2 million litres or somewhere around 80 lakh cans. This would give them a total retail revenue of somewhere around Rs 4 billion. While this is pretty high, it is less than a third of our minimum total retail revenue estimated for Sting.

This makes it very clear Sting is in a category in and of its own. Just look at it this way. In comparison to Sting, Sprite, which is Coke’s second biggest brand, sold just over 67 million litres, which is 10 million litres less than Sting.

The regulatory problem

We have a very clear conclusion here. Coca-Cola has performed better than Pepsi last year, and because of that Coke Pakistan has technically beaten out Pepsico in the carbonated drinks section. But Sting, which should rightfully be in that segment, has put Pepsico ahead of Coke. And it is also clearly competing not with other energy drinks but rather with traditional soft drinks.

Why then is this an energy drink? Well, on the one hand, Pepsico has managed to use the branding and marketing of Sting as an energy drink to great effect. But this also comes with its dangers.

Regulatory dangers.

Just take a glance back to 2018. Back then the government of Punjab ordered energy-drink manufacturers including Red Bull to remove the word “energy” from their labels, saying it is scientifically misleading and encourages a population unaware of the beverages’ contents to guzzle them in potentially dangerous quantities. The order comes amid an international regulatory pushback against the highly caffeinated fizzy drink market, and is believed to be the first in the world to censor the term “energy” – a key part of the drinks’ appeal.

As a report by The Guardian noted, the scientific advisory panel of the Punjab Food Authority said rather than provide the body with nutritional energy, the large quantities of caffeine, taurine and guarana contained in energy drinks simply stimulate the swift release of existing reserves.

Under the PFA’s order, makers of energy drinks have until the end of the year to replace the word “energy” with “stimulant” on their labels and add a series of warnings in Urdu, the national language, against consumption by pregnant women and children under the age of 12. The PFA has also demanded that energy drink manufacturers, who sell about 312m cans each year in Punjab, must limit caffeine to 200 parts per million (ppm), about half the amount that Red Bull currently contains.

The move to have these drinks relabeled and not associated with the word energy came as the result of serious lobbying. According to some, the move was in part orchestrated by Coke, which sought to curb the success of Sting. But despite this, Sting kept selling, which is why Roar was introduced a year later in 2019 when it became apparent changing the label was not going to have an effect.

Where does the future stand?

Profit is in a tricky situation doing this story. The tricky situation is that the latest date we have available is from 2023. Now, normally this data would be recent enough. Especially since we are only a few months into 2024. The only problem is that a major shift has occurred on the carbonate market since October 2023.

As a result of the genocidal actions of the Israeli entity in Gaza and the Occupied West Bank, many in Pakistan have chosen to boycott MNCs like Coke and Pepsico. As a result, initial reports are emerging that there will be a further dip in the amount that these MNCs are able to sell in Pakistan.

This may mark a watershed moment. Remember, other local makers of energy drinks make up for nearly 20 million of the litres of energy drinks sold in Pakistan. Even in the carbonate drink segment, brands like Gourmet, Sufi, and Mehran Brothers have a 5-6% share of the market. This is likely to grow.

Over the past decade, Sting has made its presence known in Pakistan. It has muscled its way into the market, become a contender for the third largest drink in the country, and has single handedly kept Pepsico ahead of Coke Pakistan in overall sales volumes. If there was ever a moment for local non-MNCs to step up and possibly muscle their way into the segment.

love your website

Well written Abdullah . Good to know we have analysts who have in-depth knowledge of business segments .