In 2016, the board of directors of the State Bank of Pakistan received a concept note for a micropayment gateway. The concept note was quickly approved with enthusiasm, and the idea for RAAST was born. What is RAAST? Ask the state bank and they will tell you that it is a one-stop fix to make digital payments faster and more convenient, and a solution to most of your frustrations with the country’s digital payments infrastructure. Ask the banks that are supposed to be using it and they will begrudgingly tell you that while RAAST has certain benefits, it is a draconian and heavy handed imposition in which they are being given very little choice.

What is the reality? For starters, RAAST is going to be a brilliant idea for the end consumer in more than one way. Transactions will be fast and take place in real time, and there will be other ease of access points that the SBP hopes will encourage the digital payments revolution they are trying to achieve. For the banks, RAAST will mean that they are free from the inefficiencies of 1Link (Pakistan’s largest interbank network) and the delays caused by the IBFT transfer system.

What are some of these problems that RAAST is planning to target? RAAST claims it will settle payments between banks immediately (which does not happen right now under the incumbent 1Link system), it will allow something called ‘bulk payment’, it will also make transferring funds easier by introducing ‘aliases’ that will act as unique bank account numbers. With RAAST will also come ‘request-to-pay’ services in which service providers can ask for payments directly.

All of these are solutions to problems that do exist in Pakistan’s digital landscape currently. All of them will go away by the time the State Bank of Pakistan has launched RAAST completely, and if the SBP is to be believed, all of these services will be provided for free. While this will make life much easier for the consumers, it will also leave other players in the financial industry teetering on the edges and not quite sure of their position any longer. The banks are already unhappy about the possibility of losing out on transfer fees and having to provide these services for free, and 1Link is expecting a major blow. And then the banks have another issue: the SBP is going to open up RAAST to the fintechs, which are the sworn mortal enemies of traditional banks.

At present, it seems that the SBP is going to get its way (as it almost always does) and that the banks are going to have to toe the line. But how will RAAST pan out, and will the banking industry be able to foil the plans if they want? Profit looks at how the launch of the SBP’s RAAST is likely to play out, and what its role could be in the SBP’s grander plan of digitising finance in Pakistan.

Setting the scene

When you make an online transfer from one account to another today, what happens exactly? To you (the consumer) it may seem that the transaction is happening in real time. For example, if you have to transfer Rs 2000 to a friend, you will simply log onto your bank’s application or website, add a beneficiary, and make the payment. Within a few minutes of making the transfer, you will get an SMS alert or an e-receipt that the transfer has been made. A few minutes after that, the person that you sent the money will have received it in their account. The only problem is that while the numbers are being updated within minutes on your accounts, something else is going on behind the scenes between your two banks.

Currently, the way transfers between banks work is through a system called IBFT (Inter Bank Funds Transfer). IBFTs are run through 1Link, which is a consortium of 11 banks that own and operate the largest representative interbank network in Pakistan. This is the same consortium that allows you to use your debit card at the ATM of a different bank from the one you have your account in. So when you transfer money online, first the transaction goes to 1Link which approves it and then it goes to the person you are paying.

However, the settlement of the money does not happen between the banks immediately. That takes place at the end of the day in the evening, and sometimes some transactions get missed out on. And if 1Link is down, for example, it is possible that money gets deducted from your bank account (because your bank has sent it to 1Link) but does not get added to the bank account of the payee, since 1Link has not forwarded the money to them. In cases like these, 1Link has to make files on every failed transaction and it can take up to 5-6 days for the failed transactions to be settled and for the money to get returned to you. In case you are making a larger payment, say Rs 200,000, you will not want to transfer the money again until your issue has been resolved.

Consider a scenario where you transferred money from your Habib Bank account to let’s say MCB Bank but the receiver or payee sends you a message that money was not received, while your mobile banking application shows that the money was transferred. What do you do then? Most likely, you will call your bank to find out what happened or the payee is going to call his bank. Maybe both of you will call your bank and both banks would perhaps say it’s the other bank’s glitch. Eventually, the phone banker will ask you to wait for a few days and after that you will get to know because somewhere in the digital payments ecosystem, that money is stuck along the stakeholders chain that include the sender’s bank, the receiver’s bank and the switch, 1Link.

You see, when you make a funds transfer from your bank account today, it first gets to 1Link because all the funds transfers are through IBFT which is the service from 1Link that banks have subscribed to for these transfers. Once the sender initiates the transaction, 1Link switch authorises and the receiving bank is credited and the customer is updated and can withdraw funds. While the transaction looks instant, behind the scenes, it is not.

The actual settlement of this transaction between banks occurs in the evening if the transaction is processed before 4pm, or the next day in the morning if the transaction is carried out after 4pm. The final settlement between banks for IBFTs happens in large value transactions through the RTGS (Real Time Gross Settlement) system – which is meant specifically for large payments between banks, not small consumer transactions and IBFTs. While the IBFTs happen at consumer level and are small value payments, the eventual settlement between banks happens at RTGS, in bulk – which is what we mean when we say that the payments are made to and from the banks through 1Link at the end of the day and not immediately.

Now what if the transaction was unsuccessful? Behind the scenes, 1Link creates settlement files of successful transactions and unsuccessful transactions and shares these files with banks the next day. The respective banks reconcile those transactions in their system a day after they receive from 1Link and after reconciliation, the sending bank looks at which transactions actually happened and the receiving bank does the same. So when your transaction is stuck, it could either be stuck at the sender’s bank or the receiver’s bank but they would only know once the reconciliation is done of these transactions and the errors are rectified but for a consumer, this essentially means that the payment is going to take some time to fall into the payee’s account, or the payer’s account if the transaction failed at payer’s bank.

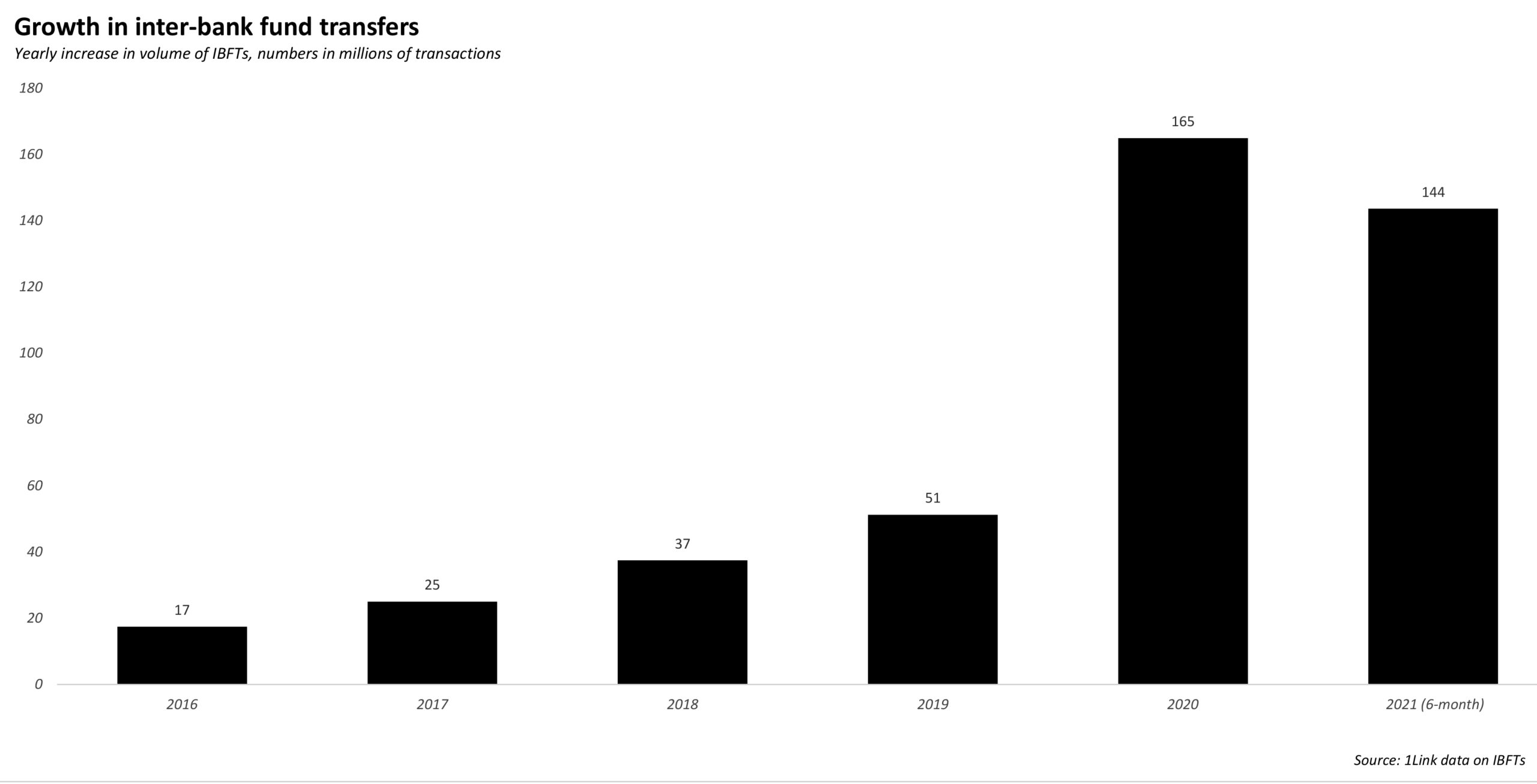

In either case, it’s a delay of a few days, with confusion if the payee will receive the money or the payer will get it back. In numbers, Profit has learned that transactions that fail like this are roughly 3% of the overall transactions but because the overall number of volume of these transactions is so high, the 3% adds up to a significant chunk of transactions that fail. In today’s numbers, 1Link processed 143.5 million IBFT transactions of various banks in the first half of 2021. 3% of these transactions failing is 4.3 million transactions in 6 months. On a monthly basis, that is 717,500 IBFTs and on a daily basis, we are looking at 23,916 transactions failing every single day.

Some, if not all, of these transactions would be carried out by salaried persons, or those who put in small amounts in banks and do very few transactions. For context, roughly 80% of the transactions on IBFTs are below Rs25,000. For persons who let’s say only have Rs35,000 in the account and they have to transfer say Rs25,000 for the sustenance of the family in some other city, transaction falling down and the money not received for a few days is plainly inconvenient to keep it soft, and an ugly digital experience for the transacting parties.

On the surface this may seem like a not so important and infrequent happening. In reality, it could not just possibly be a deterrent to people using online banking, but also a harrowing concept in principle. The issue is that the current system is not ‘instant.’ Ideally, online banking should be as easy (easier actually) than handling cash. And with cash, it is a simple matter of bills exchanging hands.

This inefficiency is exactly what the kind of problem that the SBP wants to solve. Their ultimate goal is pushing Pakistan into going digital, and with outdated systems like IBFT and 1Link, there is still a long way to go. This is where RAAST comes in.

The long winding road to RAAST

Pakistan’s road to digitisation has been an arduous one. Online banking is full of inefficiencies from adding new beneficiaries to waiting for confirmation that a payment has been made, whereas the world has moved on to new technologies that make the payments experience smoother. And for a country that has time and again resisted this kind of change in terms of money going online, even the smallest of inefficiencies let alone these very basic problems are a deterrent stopping people from using online services. The IBFT system being operated by 1Link is not exactly archaic, but it is clunky and outdated for sure.

Ideally, a system like RAAST to fix these wrongs should have been created by the private sector and not the State Bank of Pakistan. The banks are already grumbling about the fact that they have very little choice in coming on board RAAST since the directive is coming directly from the central bank – but that is also precisely the point. If RAAST had been launched by a private fintech company, the banks would never have taken the bait.

Right now, the SBP’s plan is to launch RAAST as a free of cost platform since their ultimate goal is to promote digital banking over traditional over-the-counter banking. Even with this the banks are having a hard time. If it was a private fintech company launching the platform and taking a large cut of the earning from each transaction made on RAAST, there would have been a blood-bath between the banks and the company pitching the idea. Despite this, to the SBP’s credit, they tried to get the private sector to fix the problem.

This scenario had put the SBP in a quandary. So they decided they would make regulations that would allow the private sector to come in, connect with the RTGS system, build use cases (a use case is simply a function that a website can perform – a feature that allows instant payments on a banking app for example) for retail level financial transactions, and fix the problem. Essentially, this was a call for fintechs to come in and troubleshoot the problems that Pakistan’s digital payments landscape had. Already in Europe a new payments revolution had come about after the Payment Services Directive 2 (PSD2) that provided a regulatory framework for non-banks such as fintechs to become part of the formal financial system through API-based integrations. API based integrations are systems like RAAST that allow for interoperability and immediate transactions.

To put it in simpler words – the SBP wanted a fintech company to come in, connect to the existing network of RTGS, and use that digital infrastructure to create a platform that banks and fintech could all use to encourage immediate payments and smoother interoperability between banks. Meaning no more lag times between transactions, no more failed attempts and money stuck in purgatory, and most importantly an easier user experience. They introduced regulations for Payment Systems Operator (PSO) and Payment Systems Provider (PSP) in 2014 for the private sector to come in and get authorisation from the SBP under the PSO/PSP license to digitise payments for various use cases. In the natural evolution of things, the interaction of the private sector with the SBP highlighted the need for electronic money institutions (EMIs), not banks, to make digitisation a reality. Consequently, EMI regulations were introduced in 2019.

However, this was never going to work? Why? The banks hate the fintech companies cropping up and take them as direct competitors, so they were never going to agree to come willingly on board a system designed by a fintech company and pay them money for it. In a parallel, harmonious, logical world, interoperability between various financial institutions was necessary whereby a fintech company’s application could be used to make payments to and from any bank or wallet. But because of the antagonism between the banks and fintech companies, it was virtually impossible.

However, even as it seemed that Pakistan would never be able to come up with a platform where all the banks could link up for immediate transactions, the world was moving forward. Instant payments were becoming more instantaneous and there was a need for a system in Pakistan that was cutting edge. That is when the State Bank decided to take things into its own hands and launch RAAST.

Translated as the ‘right-way’ in Urdu, RAAST was pitched to the SBP back in 2016, and it was inaugurated earlier this year in an elegant ceremony attended by Prime Minister Imran Khan, members of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation which funded the project and officials from the central bank. At the ceremony, PM Khan hailed RAAST as a major leap towards ‘Digital Pakistan’.

“Various stakeholders including international the World Bank and experts agreed that Pakistan should have an instant payment system; however the features and design of the system had to be decided. but there was no consensus then on what would be the form of this system,” says Syed Sohail Jawad, director Payment Systems Department (PSD) at the SBP.

“There are different models around the world for an instant payment gateway. Mexico for example modified its RTGS for instant payments for retail. The SBP studied different models in countries and the challenges faced during and after implementations of their hiccups. Meanwhile, the digital financial services team at Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation also liked the idea and decided to not only provide funding but also technical expertise for the new instant payment system,” says Sohail.

Consequently, in 2017, the Gates Foundation through Karandaaz Pakistan signed the funding agreement with the SBP and in 2018, Mckinsey and Co. was brought in as consultant and project manager, RFPs and EOIs were floated and the procurement for infrastructure for the project was completed late 2019. In January 2020, proof of concept was conducted and following its validation, Karandaaz signed the agreement with the vendor of the project, a Swedish company called CMA Small Business Systems, in March 2020. CMA Small Business Systems is also the vendor for Pakistan’s RTGS.

SBP says they are not aware of the size of funding received from the Gates Foundation. All procurements and financial matters relating to the project are handled by Karandaaz Pakistan which directly receives all funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Karandaaz Pakistan told Profit that the funding for the project is in the vicinity of $13-14 million.

The size of funding is another one of the reasons why no fintech company would have undertaken this project on its own. From sources, Profit has learned that the central bank had initially asked the private sector, fintech companies already operating payment gateways or new ones, to launch the instant payment system. The size of funding for the project is mammoth but to push its adoption, the regulator is poised to keep the service for consumers free which means that private companies would not be able to generate returns on the investment and, therefore, did not have a business case for the project.

What RAAST will look like

Up until now we have discussed how the SBP wanted a fintech company to come in and fix the problem for them, and how this would cost too much money and that the banks would never be on board with this. However, with a system like RAAST that is being implemented from the top up by the SBP, which is giving very little choice to the banks, there are other functions too that will make life easier for consumers and encourage digital payments.

For starters, there will be no change in interface on the banking apps. Most of the consumers won’t even know that their bank is providing them funds transfers facility through RAAST now instead of IBFT. It’s just that the experience would be better. According to Shariq, banks would prefer to keep interfaces the same because banks have had to bear through the pains of making customers get used to the interfaces that they have now. These are the major changes. These are the major changes we can expect from RAAST to improve this user experience.

Immediate payments:

This one has been discussed at length in our explanation above – what happens if you transfer money to someone’s account and it gets stuck somewhere in the process between the payment going from your bank to 1Link through IBFT and then to the person you are transferring the money to? Under a system like RAAST under which all of the banks are connected, small retail transactions are immediately recorded with the bank and there is no chance for failure in the transaction. So with RAAST, when you transfer money through your bank account to someone else, it will take seconds.

That is a ‘right way’ to do it, whereby once a customer is making a funds transfer, it is happening real-time: the money is either sent, or it is not! There are no backend reconciliations, no settlements between banks. Quite simply, under RAAST, all fund transfers will be settled between banks real-time at RTGS.

Real-time settlement under RAAST for banks also means that costs for banks are reduced. “For banks, as IBFTs increase, the associated costs also increase in case transactions are stuck. More resources are required for customer service, call centers, reconciliation team and dispute handling. I do believe this will all significantly come down with RAAST, which makes it a compelling proposition for banks,” says Shariq Mubeen, head of alternate distribution channels at Meezan Bank.

Bulk payments

In January this year, the central bank rolled out the first use case for RAAST – bulk payments for entities that do multiple payments, for instance salaries or pensions. When this system was launched in January, there were around 14 banks. Now, 30 banks have been onboarded and integrated with RAAST. Bulk payments also include dividend payments for shareholders that are done by the Central Depository Committee (CDC). It is currently working with Accountant General Pakistan Revenues (AGPR) for salaries, Ehsaas programme for disbursement of payments and Central Directorate of National Savings (CDNC) for savings payments.

If you are a customer of a bank and receive your salary in your account, or if you are a bank customer or a mobile wallet user, the most obvious question that you will pose is that you already receive your salary and you already make funds transfers through your banking application, so what is new here? Or what exactly is RAAST going to change?

The quick answer is that payments would now be settled immediately and the transactions are going to be swift. So, as we mentioned in our scenario, your colleague is no longer going to get their salary before you because when accounts send out salaries, it will all happen in one fell swoop.

Right now, for instance, all your salary transfers are done through IBFTs by your bank which are done one after the other. So RAAST bulk payments are going to change that instead of doing these transfers individually, the payments are going to be done in one go. If it is 500 employees, the payment will be pushed all at once instead of individually. If it is 1,000 employees, it is going to be pushed for all the employees at the same time, making these payments more instantaneous.

Aliases

This is another simple and compelling feature of RAAST that would simply add to ease of making digital financial transactions, deterring cash transactions and promoting financial inclusion.

To use a personal anecdote, I recently witnessed an instance of a bank transfer that was pretty anomalous and by chance got to know what sorts of problems having the ability to create aliases can solve. The instance was simply a friend transferring money from a Bank Alfalah account to a UBL Bank account. The transaction would simply not go through and later it emerged that UBL Bank had three formats for account numbers. The account number could have branch code in the beginning, in the end and in one format, they would have branch code followed by branch code again and then the account number but the banking applications would only recognise one format.

Under RAAST, the UBL account number, in whatever format, could be linked to an alias for instance the phone number of the customer, and next time he asks someone to send money to that account, he could give that phone number to the sender and the sender’s banking application would automatically recognise which account that number belongs to and the transfer would be processed happily.

Imagine the utility of such aliases for the unbanked that are still unbanked because of the troubles remembering or putting in account numbers because they are not literate enough. For these transactions failing because of complexities associated with account number formatting issues in the case of UBL, and for a few, complexities associated with remembering and putting these account numbers in banking application and processing transfers means that such errors and complexities could deter digital transactions, end these transactions even before they could start which can eventually promote cash transactions.

Request to pay

R2P (request to pay), or pull payments as they are known in digital payments nomenclature, are the opposite of fund transfers that you do under which payments are pushed from one account to another. Currently, for example, if you want to pay your child’s school fee through an online transaction you add the school as a beneficiary and pay your child’s fee. This means you have to remember the due date, log into your account, add the school’s detail, add the exact amount and purpose of payment, and then send a receipt to the school and wait for confirmation as you have the payment is not among the 23,916 failed transactions that take place every single day.

Under R2P, your child’s school can ask its bank to enable R2P for fee payments and instead of sending you a fee voucher, you will receive a message or an email from the school, informing you that your child’s fee is due, with a request to pay. You agree to pay through a link in that message and email and your child’s school fee is processed. The convenience there is that as a parent, you could slack on your child’s fee if you have to pay the fee yourself, even if it is over a banking application. You’d be in office, you would forget to pay because of recurring meetings at work. Same would happen the next day, and the next. But if the school initiates this payment for you, chances are that you would pay immediately.

With EMI regulations in place, new fintech companies can potentially cause massive digitisation on the back of R2P, digitising entities like schools, public entities like K-Electric could request bill payments from you, and banks can R2P the loans back. From what we have learnt, banks foresee a huge surge in transaction volumes because of R2P, and huge volumes mean that the system would have to be robust and does not fall down every other day. And as we have come to know, RAAST is a system which is capable of handling large loads of transactions, and yet gives the best performance.

R2P is one use-case, however, which the SBP is proactively pushing itself. But use-cases will be continuously developed by banks and EMIs, even on R2P, for instance P2G (person to government) payments or corporate to corporate payments could be built on RAAST by an EMI. The EMI would simply have to request the SBP to create the use case on RAAST and make the API for that available to the EMI, and everyone including the banks would have to work with the EMI; it would be interoperable.

Officially, fintech companies look forward to working with the SBP on RAAST. “Low-cost, contextual rails, quicker access and settlement is just what is needed for scaling digitisation across multiple verticals,” says Omer bin Ahsan, Lead Regulatory Liaison Pakistan Fintech Association (PFA).

Who regulates the regulator?

As mentioned earlier, one of the reasons why the SBP is the one undertaking RAAST and not a private company is because a private fintech company would not be able to get everyone onboard for the adoption of the project, and also because a private company would probably have a hard time getting its hands on the kind of money that it needs to do a project of this magnitude.

Take 1Link for example. From sources, Profit has learnt that by virtue of it providing IBFTs to financial institutions, it had also developed R2P and presented the same to banks, which was shunned by the banks because R2P means deposits would be moving out of banks, towards smaller banks. Consider an EMI that has its primary account with a small bank, let’s say JS Bank, and develops a R2P use case. In this case, R2P payments would mean customers that are using the EMI’s service, if they are with big banks such as HBL or Meezan Bank or UBL, money in form of payments would be moving out of these banks into JS Bank. The banks dread their deposits depleting, which is why 1Link could not do it. But banks also dread turning down the regulator, the SBP, when it asks them to do something which is why RAAST is going to do well, even though they would have some apprehensions about the project.

From industry sources, Profit has learnt that banks are wary of the regulator because the banks are hard-pressed when it comes to SBP directives that it pursues seriously. RAAST is one of these projects where the banks had to prioritise the SBP projects over their own projects despite concerns like the R2P use case.

Pricing of RAAST is another aspect where there is going to be some sort of contention between the SBP and the banks and branchless banking companies JazzCash and EasyPaisa in particular, and which could at least slow down the RAAST revolution despite its benefits to the banks.

When Covid-19 hit, the central bank was quick to move to remove charges on interbank fund transfers, which was followed by rounds of lobbying from the financial institutions, JazzCash and EasyPaisa, in particular because IBFTs are a revenue source for banks, and one of the few income sources for branchless banking players. The waiver on IBFT charges was removed, however, and a tiered system of charges was put in place where financial institutions can now charge 0.1% or Rs200 on transactions above Rs25,000. Transactions below Rs25,000 aggregated in a month are free of cost.

For banks, IBFTs are a business case that incurs a cost and generates income for these banks. It is a significant case for EasyPaisa and JazzCash because these financial institutions do not have many avenues of making money and IBFTs form a big chunk of their income. Which is why both EasyPaisa and JazzCash were the frontrunners in getting charges on IBFTs restored.

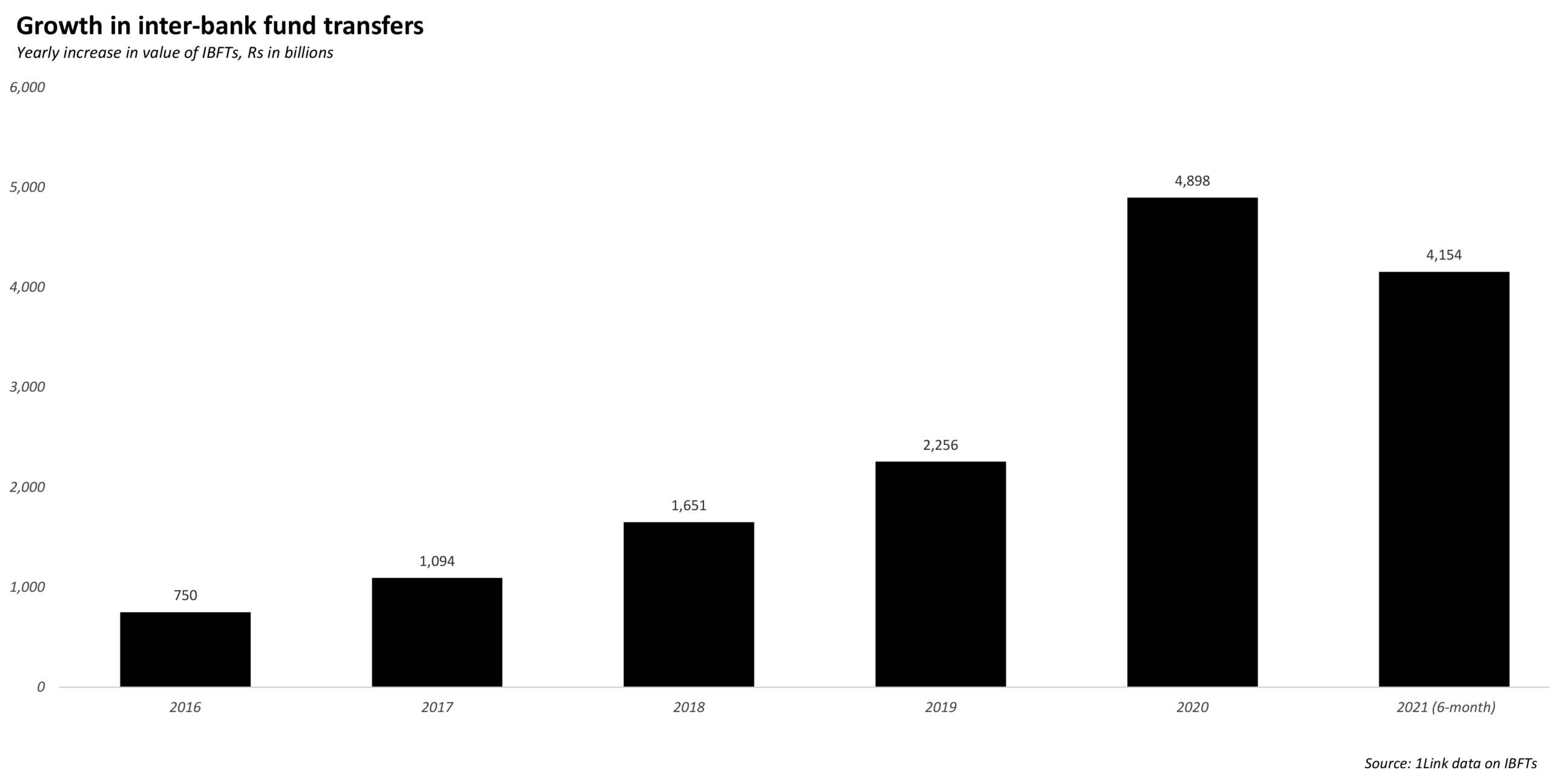

But the SBP is poised to improve the adoption of RAAST and the earlier waiver on IBFT charges resulted in a massive surge in IBFT transactions. From 1Link’s numbers, IBFT transactions for the year 2019 were only 51.2 million in volume and Rs2.2 trillion in value, whereas for the following year when Covid hit and the waiver was announced, IBFT transactions in volume spiked by over 200% to 164.9 million transactions and value-wise, the spike was over 100% with Rs4.89 trillion processed by 1Link as IBFTs.

The sheer increase in IBFT numbers, though it is unclear if the rise in IBFTs was on new accounts or there was more depth in the existing IBFT transactions, provides the required conviction to the SBP that if prices are kept low, adoption of digital payments would increase. Consequently, the SBP, in our conversation with them, showed an inclination of keeping the charges for RAAST free for banks and also mandating banks to keep these charges free for bank customers. The financial institutions would, however, be allowed to charge for the innovative use cases that they bring as value added services.

But banks contend that setting up systems at banks to connect with RAAST is coming at costs for them and that they should be allowed to charge at least what the charges for IBFTs are right now for RAAST to make business sense.

You see, RAAST is currently run by the SBP itself, with a steering committee at the central bank acting as a governing board. The project is currently being run with operational costs being borne by the regulator and in our conversation with the regulator, the SBP is likely going to run it itself for the next 2-3 years. Since the project is all about spurring digital payments, the regulator would try to incentivise adoption on low cost transactions for consumers as it has seen an adoption in IBFTs on the back of the waiver it announced last year.

But the important question here is who would regulate the regulator for as long as it owns the project? The SBP is a powerful regulator that finds its way around doing things and banks are wary of dealing with the regulator. However, the SBP assured us that even though they are regulators with goals for the economy, they are a rational regulator that has to comply with international standards of regulating financial institutions.

“In payment systems, there is a function of oversight which is different from supervision in banks. This oversight is done under as per international standard developed by the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) called. These standards apply to all systemically important payment systems, central securities depositories, securities settlement systems, central counterparties and trade repositories (collectively or “financial market infrastructures”). As SBP owns and operates Pakistan’ Real-time Gross Settlement System (PRISM), we also perform self-assessment against those principles and measure compliance. SBP also advises systemically critical payment infrastructures like 1Link and NIFT to conduct their own self-assessments according to these principles,” says Sohail Jawad.

“Our internal audit department is also vigilant and we have segregation of duties at the SBP. Recently, we have created a Digital Financial Services Group at the central bank by bifurcating the existing payments department into payments policy and oversight department and settlements and digital innovations department, which means oversight is going to be more effective and innovations in payments space would have more focus by the regulator,” he adds.

Another point of contention, and a broad problem in the financial services landscape of Pakistan, and which is why the SBP chose to launch RAAST on its own, is that onboarding of fintech companies is full of friction, with banks having their own agendas. (Read more on the problems in the financial services industry: FAP vs PFA: Who has the right credentials to lead Pakistan’s fintech industry?). Secondly, banks, being the biggest players in the financial services, have till now not prioritised digital payments, which is why QR codes haven’t taken off in Pakistan. (Read more on QR codes in Pakistan: QR codes did not bring a payments revolution. That doesn’t mean it’s over). Sometimes, banks would be wary of opening their customers to an outsider, sometimes, they wouldn’t simply prioritise innovative payment methodologies, like QR codes, because they do not want to give up on their cash cows; Visa and Mastercard, which new payment methods would be cannibalising.

Banks simply act risk-averse when it comes to digital payments.

On the other hand, fintech companies want an in the financial services industry because there is simply so much gap that is left that can be fulfilled, in an agile, cost-saving manner. But banks would refuse to expose their customers to the new players which they perceive as competitors. It is only logical then that when it came to RAAST, SBP was perhaps faced with a stiff choice of doing it itself, get it up and running and let a new order for the entire sector take shape where fintech is an established industry and banks are also comfortable working with them.

But the regulator running RAAST has worried many. The central bank, however, is possibly going to act rational. It knows where and when it is transgressing and makes amends when it does. The example we have is the restoration of charges on IBFTs. The SBP realised that though banks have other avenues of making money, JazzCash and EasyPaisa would suffer because of the waiver and the regulator eventually realised and rationalised the charges to some extent.

Aftermath: Future of IBFTs

One of the reasons why RAAST was launched was because the entire funds transfer infrastructure was relying on one entity: 1Link. Simply letting the entire infrastructure rely on one entity and any failure at 1Link would be a systemic risk. Imagine 1Link IBFT crashing, though it has never happened before but the risk is still there, and the entire systems of funds transfer stopping.

In a sense, RAAST was created as a back-up option but because it is cutting edge and advanced in terms of technology that gives a better payments experience, it would be the primary system for most banks if not all and 1Link would become the fallback option for these banks. “1Link could potentially be a backup option. For instance, if there is an upgrade at RAAST and the system is down, banks can have the option to immediately switch to 1Link and carry out funds transfer to ensure uninterrupted services. However, it depends on 1Link’s decision to continue to exist in this space,” says Shariq.

The few things that are going to matter to banks for choosing RAAST or IBFT for funds transfer are price and service quality, on which RAAST tops for now because of the advanced technology and infrastructure. On price, IBFT makes more sense because banks are allowed to charge on transactions above Rs25,000 aggregated in a month and RAAST also makes sense for banks when they are allowed to charge at least as much as they do for IBFTs to consumers.

1Link witnessed an unprecedented growth in the IBFTs during Covid-19 lockdowns and the waiver, but is buckling up to take a hit as more banks onboard RAAST. “We cannot quantify yet, but we are expecting some hit on our IBFT transactions in cases where there is direct settlement in RAAST without 1LINK involvement,” says Najeeb Agrawalla. Though Najeeb also says they can also potentially introduce real-time settlements for banks if SBP mandates, just like RAAST, but refused to say definitively if and/or when that would actually happen. Even with a hit on IBFTs, as an entity, 1LINK is sustainable on the back of the ATM switch which powers the entire ATM infrastructure of the country, PayPak, Fraud Risk Management Services and through its services as a bill aggregator for various entities.

While 1LINK‘s IBFT appears to be a competitor to RAAST, 1LINK is planning to join the RAAST network for faster payments for other services that it provides, or to introduce new services. 1LINK’s legal and commercial arrangements with banks, billers, EMIs, PSO/PSPs etc., indicate that these arrangements will help 1LINK leveraging RAAST for a better service delivery to the industry.

Aftermath: Future of debit cards and payment schemes

How do you make payments at a merchant today? If you go to a big retailer, you can pay through cash or your debit card/credit card. If you go to a small retailer like your neighborhood kiryana store, you would be able to use cash only. These are the only two methods you can use to pay a merchant today. An important component of the central bank’s digital payments strategy is to roll out another method of payment, QR codes, through the RAAST instant payment system.

As a customer, you would be able to scan a QR code in plastic at a merchant, or you could scan a code through your wallet or banking application right off your merchant’s phone then and there and the payment will be processed.

QR codes have not been successful in Pakistan. As earlier mentioned, interoperability has been a big problem where banks and wallets won’t open up to other banks and wallets. The case has been the same with QR codes for payments. For instance, JazzCash and EasyPaisa have proprietary codes in the market but those can only be scanned using the JazzCash and EasyPaisa mobile wallet applications. If you have a mobile banking application on your phone, came across a JazzCash or EasyPaisa QR code but could not scan it to make a payment, it is because these QR codes have not been opened to your bank by the respective branchless banking companies.

So if the SBP is able to roll out interoperable QR codes, essentially, that would be replacing cash and debit cards. While cash could be considered a bane that even banks would want to replace, debit cards are lucrative cash cows for banks that help them replace cash.

A banker once told us that debit cards are very lucrative for banks that help them earn income via the merchant discount rate and the hefty annual fees. And that it would hurt them to see their debit card income go down if QR codes come into the market (Read more on how much money banks make on debit cards: SBP wants the cheap PayPak to be the default debit card; the banks don’t).

The vested interests of banks in keeping QR codes out of the market means consumers have less options of making digital payments. The current methods of payments are costly as compared to QRs, and all this means that the country would not see the spur in digital payments that it desires. As a matter of pride, it also does not look good for a country to not have advanced modes of payments.

While it is going to hurt banks if debit cards go down, importantly, it is going to hurt the payment schemes Visa and Mastercard primarily if their cards in the market go down, or don’t go up because there are QR codes out there. The payment schemes have made concerted efforts to aggressively sell these cards to banks through lucrative incentives, and they have been doing this for decades now.

Visa and Mastercard, and even China UnionPay, have QR codes in the market that they have recently started focusing on because they have foreseen a decline in debit card income. But in any case, debit cards are more lucrative than QR codes. The MDR on debit card transactions is 2.5% whereas on QR codes, it is 1%. Payment schemes get different cuts from the MDR charged to merchants and a bigger percentage means a bigger cut for the payment scheme. For banks, it is more lucrative because they get a cut from the MDR and earn issuance and annual fees.

So if the central bank successfully achieves interoperability for QR codes, these payment schemes would be in a fix. The more important question, however, is whether the SBP will be able to push QR adoption in Pakistan. The State Bank’s plan is quite visible: they want to make sure low cost modes of payments like QR codes are available. But critics say QRs have really been a success in China and a few Southeast Asian nations and for successful adoption of QR codes, these QRs would have to penetrate deep into streets in towns and cities at kiryana stores for it to be called a successful adoption. If that happens, the volume of transactions then would be significant enough to recover the income lost on debit cards for banks and payment schemes. But that is a big if.

For now, in our conversations with bankers, we could witness the tension in their voices when it came to QR codes replacing debit cards. Tensions in voices means reluctance and reluctance would lead to banks finding ways to block adoption of QR codes. So with a nation badly needing a serious push in digital payments, a regulator ready to give that push and hesitant banks and payment schemes, we can only hope that RAAST is able to live up to its promise.

One of the most objective and well researched articles I’ve seen this publication write. There was a lack of a reference piece for the general public on something that is likely to alter the experience for the common customer irreversibly. I think something like this should also be covered via video on Youtube to make it even easier for people to consume.

A big round of applaud for the article. You cover each and everything very nicely. There is a dire need of new entrant like RAAST to compete with 1link with well improved way.

I really like the raast system i been using ubl digital app but they never mentioned this service. Government should advertise this system and also make their own UI app and customers after link up raast service with there accounts should able to login in raast ui app.

Wow, really want to see such articles in the future. Didn’t want to read for a minute on other platforms but here read it all. Amazing

What about risk of increase in digital frauds with this digitalization? Any undue advantage to the hackers?