Coal is facing the firing squad, or that is at least what the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference, more popularly known as COP 26, would have you believe. As world leaders gathered at Glasgow to determine how the next three decades will go in terms of climate policy, one of the key points circulating within the media has been putting an end to coal and focusing on clean energy.

Yet the ones calling for an end to coal, which is technically a just cause, are the leaders of developed countries that have for decades built their economies on the back of a persistent and dangerous use of coal. Now that their economies have developed, they expect countries that are still developing to give up on that opportunity. Pakistan is one of these countries, and it is in fact one of the countries that will possibly be ramping up its usage of coal in the near future.

This is one example of the many inequalities that play out at conferences like COP 26. Countries in the first world have a large debt to pay in terms of the destruction they have caused to the earth’s natural environment. Their role in climate change has been disproportional, yet small states are the ones that are often expected to give innovative solutions and take on a lot of the heavy burden.

This year has been a watershed moment for Pakistan in terms of its global role in climate action. The Pakistani delegation has been impressive in some ways, particularly with flashy programs like the Billion Tree Tsunami. It has also impressed by being very vocal about the need for climate financing, calling out world leaders for once again delaying a decades old promise.

However, what has been even more impressive is that the Pakistani delegation has not shied away from subverting the direction of the conversation and questioning the role of developed countries in fixing the problems that they have so overwhelmingly contributed towards.

Unlike other countries in the region like India and Nepal, Pakistan has not committed to a carbon neutrality policy and has also maintained that while it will not introduce new imported coal projects, it will also not consider ending coal power as of yet. As the Pakistani delegation points out, it also needs to look after its own economy.

As Malik Amin Aslam, the adviser to the prime minister on climate change, and the rest of the Pakistani delegation fight a topsy turvy battle in Glasgow, back home climate activists and corporations alike are also taking a stand. And while there remain serious differences in how to tackle the issue of climate change, one thing that is becoming clear is that it is a subject that both the government and some corporations want to take seriously. A fascinating instance was a recent radio panel discussion which was dominated by Ghias Khan, the President of Engro Corporation. Alongside Azifa Butt, senior manager for the WWF, Durlabh Ashok of the WEF, and Yasir Hussain, who is the founder of the Green Pakistan Coalition, the panel tried to strike a balance between fighting the climate change menace while keeping a Pakistan first outlook and taking care of our economy.

It is not often that we find ourselves in a position where we must defend Pakistan or take the side of the government. To be clear, that is not what we are doing now. There are serious flaws in both how the government and local corporations are planning on addressing the very real and very dangerous climate issue, especially since Pakistan is the fifth most polluted country in the world. However, it is also worth looking at the fact that conferences like the COP 26 regularly ascribe blame and responsibility to smaller countries for not achieving targets that they themselves are only able to achieve because of the decades of development they managed to get on the back of dirty fuel. So if Pakistan and other countries take a stand and speak out over the slowness of the conference to release funding, which has once again been delayed, then we hope it will make the world stop, turn, and take a good long look at who is really to blame.

What is COP26?

If countries gathering under the banner of the UN to discuss the environment sounds familiar, it is because it has happened numerous times before. COP stands for ‘Conference of the Parties’ and the ongoing summit in Glasgow is the 26th such meeting of world leaders. The conference was born in Germany in 1995, which hosted COP1. Back then, the conference was arranged on an emergency basis as it was becoming very clear that climate change was a growing problem. The understanding among the scientific community that the world was warming up rapidly and headed towards environmental and ecological disaster had already been around for decades, and this was the point where politicians and world leaders were finally taking it seriously.

COP1 in 1995 was in essence talks between world leaders brokered by the UN. Taking place in a world freshly emerging out of the shadow of the cold war, it seemed that perhaps the end of a bipolar world would mean it would be easier to reach consensus over how to confront the problem. COP1 achieved the goal of reaching a general consensus that it was important to reach net-zero carbon emissions (an idea Pakistan has refused to pledge to this year). The next major development came in 1998, when COP3 took place in Japan. This resulted in the Kyoto Protocol, which legally bound countries to reduce emissions.

However, the first cracks began to appear when the biggest emission producer in the world, the United States, refused to join the Kyoto protocol. Their reasoning was that developing countries like China were not bound to follow the protocol, despite the US and other developed nations having a far higher impact on the entire globe. After this, there was a stalemate, and all COPs after 9/11 received very little attention and climate change slid to the back of the global agenda.

It was not until COP15 in 2009 that the world’s attention was on the COP meet again, which is also when world leaders promised to provide $100 billion in climate financing to developing countries (this will become very important in the context of COP26) by the year 2020. The next big step came at COP16 in Paris in 2015, which is when major world leaders bound themselves to the Paris Climate Agreement. That was until US President Donald Trump pulled the US out of the agreement, once again leaving the biggest polluter in the world free of any consequence or responsibility.

However, there was extra attention on COP26 because incumbent US President Biden reentered the Paris Climate Agreement and promised sweeping changes at COP26. The world was also watching because 2020 has passed and the promised $100 billion have still not been made available and the financing has once again been delayed. As the world watches, COP26 has become a pivotal moment, and this time it seems like developing countries including Pakistan have come with a purpose, and their voices are being heard.

The threat

“Throwing coins in the Trevi Fountain is not going to wish climate change away,” says Malik Amin Aslam in an interview given to The Third Pole. It is one of the many statements in which Aslam has shown grit and shown that Pakistan is unhappy with climate financing. The Pakistani delegation to COP 26 has also shown resilience in terms of sticking to its guns and insisting it will pave its own path instead of blindly making pledges it will then never be able to meet. “In Pakistan, we don’t believe in the net-zero concept at the moment. We believe in the concept of a decisive decade in the next 10 years. If the world does not change in the next 10 years, then we’ll be too late for any net-zeros in 2050, 2060 or 2070. I believe that net-zero if it translates into concrete action in the next decade is good, but most of these announcements are just announcements.”

Conferences like the COP 26 often get a lot of attention because big names are there. But as we saw with the now widely ridiculed picture of world leaders flipping coins for good luck in dealing with climate change, much of it at times can be pomp and show. These conferences are well and good, and a lot of times they are an important meeting point to get the wheels turning on forming an international policy to tackle an international issue.

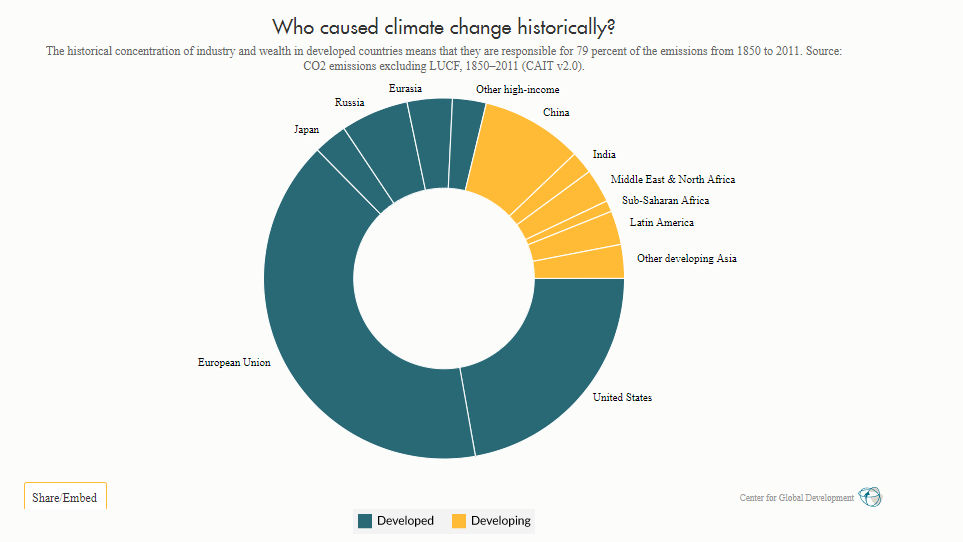

According to the Center for Global Development, developed countries are responsible for 79% of historical carbon emissions. Yet studies have shown that residents in least developed countries have ten times more chances of being affected by these climate disasters than those in wealthy countries. Further, critical views have it that it would take over 100 years for lower income countries to attain the resiliency of developed countries. Unfortunately, the Global South is surrounded by a myriad of socio-economic and environmental factors limiting their fight against the climate crisis.

“What has the developed world done in the last few decades? First world countries that are now considered to be developed were the ones that used coal power excessively and without restraint to get to the position that they are in currently. Now that the consequences of those decisions are knockin on their doors, they are looking towards the third world to go green and help everyone out,” says Engro President Ghias Khan in the earlier mentioned radio panel discussion. According to him, despite the history of how we got here, Pakistan does not have a choice in terms of what they have to do. “We are the fifth most polluted country in the world. Our future is at stake here and we can either sit around pointing fingers or do something about it.”

One of the core issues has been the fact that the developed world faces an existential threat not because of their own actions, but because of the actions of first world countries throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Currently, Pakistan has been slow to acknowledge in so many words the history of how the world has gotten to this state. What they have managed to do is state very clearly what Pakistan can do. “We’re trying to link up our financing streams with clear performance indicators on nature. We have floated our first green bond which is US $500 million for renewable energy. We’ve done the national capital evaluation for our blue bonds, with mangroves, and we’re also looking at nature performance bonds which link up debt relaxation or reduction with nature performance,” says Malik Amin Aslam.

“We have committed to no new imported coal projects. We have followed this up with clear action by shelving two projects of 2,400MW, which were already signed off. We have shifted to 3,700MW of hydropower. We have also decided to look for the best available technology which would be less polluting. We’ve worked on some options which have been used in South Africa, but we’re still searching for the best available technology. That’s what these forums should be able to provide.”

This kind of clarity is rare which is why it is refreshing. The Pakistani delegation still needs to be stronger in its decisions, but this is perhaps the first time that a delegation has gone from Pakistan that is providing data, research, numbers, and is letting the world know what it can commit to and what the world must do to help countries like Pakistan on this journey. Pakistan has shown initiative by doing things like signing the US-led global methane pledge, which agrees to cut methane emissions by 30% by the end of this decade in an effort to tackle climate change. In addition to such moves, the Pakistani delegation has still struck a fine balance and managed to remain clear in its purpose while advocating for its own interests and the interests of others in the region. And the most important aspect of it is climate financing.

The importance of climate financing

None of this takes away from the fact that Pakistan, like other countries, has a major emissions issue, however, there is a difference between allocating emissions and allocating responsibility for those emissions. The developed world has a massive emissions debt that it must pay to the developing world for the damage it has caused them.

One of the real sore points has been climate funding worth $100 billion that was promised more than a decade ago. The promise was made twelve years ago, at a United Nations climate summit in Copenhagen, rich nations made a significant pledge. The pledge to put in $100 billion a year towards less wealthy nations by 2020, to help them adapt to climate change and mitigate further rises in temperature. That promise was broken. Figures for 2020 are not yet in, and those who negotiated the pledge don’t agree on accounting methods, but a report last year for the UN1 concluded that “the only realistic scenarios” showed the $100-billion target was out of reach. “We are not there yet,” conceded UN secretary-general António Guterres.

A recent article in Al Jazeera pointed out that developed countries must make good on their promise to provide $100bn per year, through to 2025, to support climate action in developing nations. This decade-long pledge must finally be honoured – both to deliver the intended effect on the ground, and also as a fundamental issue of trust. The amount is equivalent to just 0.1 percent of the combined annual gross domestic product (GDP) of advanced economies, or about 5 percent of the $2 trillion the world spends each year on military. Promises should be kept.

“Secondly, this funding must recognise the need for us to adapt to the ongoing effects of climate change, as much as it supports efforts to mitigate it. The number of climate-related disasters within the Commonwealth, for instance, has doubled from 431 between 1980 and 1990, to 815 between 2010 and 2020. Over the last decade, these killed 48,000 people, affected 677 million and caused $197bn in damages. We are not dealing with a challenge for the future – the crisis is already here,” the article went on to say.

This is an issue that has been discussed in Pakistan as well. “COP 26 has been planning on providing this financing for a while and it was supposed to come in 2020, and now it seems it will be delayed to 2023. There are major issues with this,” says Ghias Khan. “If I was in the Pakistani delegation, I would make my strategy very clear. What will the developed world do for our balance of payments? Yes we have to go environmentally friendly, but we can’t do it at the cost of raising our imports and decreasing our exports so that people suffer from inflation even more. That is the approach we must take.

This funding is a point of unity among developing countries. “We’ve done our arithmetic on the emissions and believe that with the sequestration projects that we’re doing, Pakistan could well be on its way to levelling all its emissions,” says Malike Amin Aslam. “Our NDC shows that we’ve gone 9pc below our business-as-usual trajectory in 2020, and we can go 50pc below by 2030. It’s a very clear directional target, but we have made it conditional on getting US $100 billion of finance which can allow us to make a clean and just energy transition.”

The problem, of course, is that not everyone agrees on what to do if this funding is finally released.

What are corporations and the govt doing?

“First world countries built themselves on the back of dirty fuels and now it is time for them to pick up their slack,” says Ghias Khan. He makes a very ardent point. Engro’s approach, as an example of a corporation, has been impressive. They have taken on board experts, they plan to go net-zero soon, and they are going to be investing in net-zero businesses anytime they invest in a new business. As Khan explains, it is not just virtue signalling but they feel it is what they need to do to remain competitive. However, there must be a reward for their efforts and as part of repaying their emissions debt, the developed world must give some benefits and perks to corporations like Engro working in the third world.

“Climate responsibility is at the heart of our policy. We want to be globally competitive and for that we have to be globally up to date,” he says. “We have looked at carbon footprint and our water usage and are trying to get to net zero. It is all about how we develop our future businesses, which are all going to be sustainable, and how we fix our old businesses and gently bring them into the fold of sustainability. It is not a choice for us anymore. There are sustainability metrics in place, we recently signed an agreement at the WEF where we were the only Pakistani company to sign these matrices and made a public pledge to this.

“Imagine the sea going up to the Punjab border in a hundred years. Right now inequality is already extending in Karachi the rest of the city will be below any proper living standards. We have to micromanage these things,” says Yasir Hussain, the founder of Green Coalition Pakistan. For him, it is about striking the right balance between the present human cost and the cost we may have to pay in the future. “Labour unions and greens have come together on this in Germany for example, so why can we not do the same in Pakistan? The effort needs to be concentrated. If we are planning on producing plastics more efficiently, then we must plan on training the workers at those old plastic factories to learn how the new production methods work. All the people with stakes need to be on board.”

“We are tracking ourselves. We are managing plastic waste as well and we are doing a lot of internal research,” says Ghias Khan. “The issue is not plastic but how we manage plastics and how we invest in the circular economy of plastics. Science has yet not come for a replacement of some plastics, but Pakistan is importing from bad ways to make it. We want to adopt new, good tech that is sustainable for the environment. We will offset the rest with tree plantations.”

“This transition is new to everyone, and it becomes a very complex subject because it has also become economically viable and thus that much more important for companies. However, we have not used our natural resources for decades. Remember, Thar Coal is going to produce at 11rs/kw. We have to save dollars and we cannot afford to waste it. We have to look at it from a local perspective as well. We need to be helped through this problem, because the developed countries need to realise this and provide market access, tech transfer, and cheap financing, including that $100 billion.”

This is one place where the government has not shied away either. They do feel that while it is a threat that must be addressed immediately, before they get into any kind of pledges, they need to keep a Pakistan first mindset. “We’re not talking about climate change in a silo, we’re shifting the direction of our mainstream development towards being climate-friendly. That is what really needs to happen all across the world. Pakistan is still responsible for less than 1pc of global emissions – even if we closed down everything in Pakistan, it wouldn’t matter for the world. What does matter is that a country like Pakistan is paving the way towards climate-friendly development, based on nature and based on clean energy,” says Malik Amin Aslam.

“The leaders’ summit to me was a disappointment. Of the big five, two didn’t turn up, and the third came up with a joke of a 2070 announcement. The remaining two have been trying, but I don’t think they’ve reached the mark,” he added. “The big disappointment is US $100 billion [in climate financing for developing countries] which has been pushed now to 2023. It’s a decade-old promise – if they cannot deliver that, it’s meaningless to expect delivering a very ambitious climate agenda.”

“We’re still hoping for the best, not for Pakistan but for the world. Climate finance is central to all of it, because every transition requires finance. If finance cannot be directed towards this pathway, it just shows the big 20 polluters are not serious. Throwing coins in the Trevi Fountain is not going to wish climate change away.”

The writer and interviewees talked most of the time about development of developed countries which they attained through polluting the environment. Other thing, which was also consistently discussed, was USD 100 billion needed to be given to developing world.

The writer himself told that Pakistan is the fifth most polluted country. Yet he didn’t bother to discuss the responsibilities of Pakistani government towards its people for their safety from the bad effects of climate change. For example, he didn’t talked about how Pakistan is developing its road infrastructure in cities which is suitable only for cars which run on subsidied fossil fuel. It is pertinent to note that both cars and fuel are imported. Pakistan government has made its country the home of imported SUVs and Saloons.

It seems writer is obsessed with USD 100 billion, but he is not alone. Other people also have eye on these Doller. For example, the Philippines is saying that it will cut emissions by 75% by 2030 if it is showered with cash. If it is not provided financial help the cut will be just 3%.