The only airport in Larkana, the district home to the Bhutto family, is at Mohenjo-daro, about 30 minutes south of Larkana city, and about an hour south of Garhi Khuda Buksh, where both former prime ministers Bhutto – Zulfikar and Benazir – are buried. Standing in the ruins of Mohenjo-daro, it is impossible to escape a sense of history, and marvel at the length of the history of human civilization in our part of the world.

It is also impossible – as a resident of Karachi – to not look at the drains that run alongside literally every single street in that ancient city and not feel a spurt of homicidal rage at the Bhuttos and the party they lead, the Pakistan Peoples Party, which rules over Sindh and its capital city of Karachi. Around the time the Great Pyramid of Giza was being constructed, and 2,000 years before the founding of the Roman Republic, there existed a city in Sindh that had drains that have lasted thousands of years after the city itself perished, all while the current capital of Sindh drowns after the faintest of rain spells.

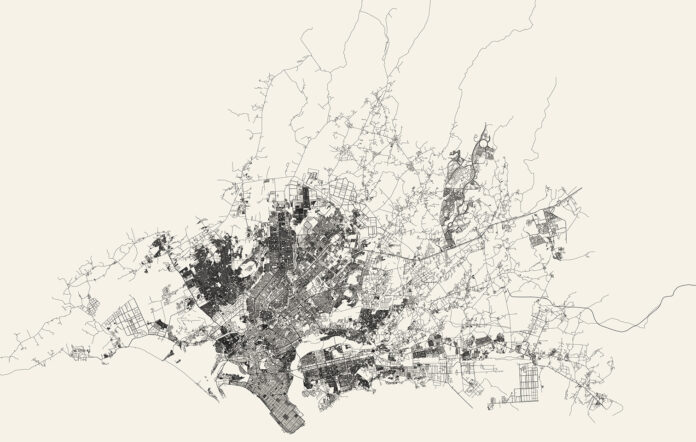

Karachi, the financial capital of Pakistan, still its largest city, and its single largest concentration of middle class economic opportunity, is one of the most dysfunctional large cities in the world. There are many historical political reasons why Punjab’s politicians dote over Lahore, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa’s politicians have finally gotten around to building up Peshawar, but Karachi languishes in neglect so willful as to border on malicious.

We are a financial publication, so we will largely stay out of the political commentary of it all. And we will also not engage in the canned blather of “the resilience of Karachi” nonsense. No, this is the unhappy tale of the sad fact that Karachi is being strangled and struggling to breathe.

That struggle is reflected in the economic map of the city, where the rich, middle-class and poor all pay in one form or another to deal with Karachi’s dysfunction. The rich pay in money, the middle-class pay in time, and the poor pay with their health.

Five years ago, prompted by the same monsoon-driven madness witnessed on Karachi’s roads this year, we wrote about how the country needs its largest city to help lead its economic growth story, and talked about the role the government could play in helping make that a reality. We have since abandoned such naïve hopes about anything positive ever coming from the government. The content in this publication is expensive to produce. But unlike other journalistic outfits, business publications have to cover the very organizations that directly give them advertisements. Hence, this large source of revenue, which is the lifeblood of other media houses, is severely compromised on account of Profit’s no-compromise policy when it comes to our reporting. No wonder, Profit has lost multiple ad deals, worth tens of millions of rupees, due to stories that held big businesses to account. Hence, for our work to continue unfettered, it must be supported by discerning readers who know the value of quality business journalism, not just for the economy but for the society as a whole.To read the full article, subscribe and support independent business journalism in Pakistan

The ongoing infrastructure problems in Karachi largely stem from the PPP, in partnership with the establishment, consistently ensuring minimal effort and investment toward lasting solutions. Projects only appear when there is obvious financial incentive, leaving citizens waiting for basic services. For example, while Karachi’s real need is a comprehensive mass transit system, efforts have focused more on launching expensive metro bus lines (Red, Green, Orange, etc.) rather than prioritizing the **Karachi Circular Railway (KCR)**—a project that could leverage existing rail infrastructure to relieve traffic congestion and upgrade public transport. Globally, cities invest heavily in rail networks, recognizing their long-term value, but in Karachi, despite a dilapidated network that could have been restored for city-wide benefit, political and bureaucratic delays persist. Recent reviews by Senate committees show KCR remains stuck due to land transfer disputes, slow follow-up, and delayed approvals, especially from international partners like China. The project still struggles to get off the ground even in 2025, as vested interests and administrative inertia stall progress. In contrast, significant funds continue to be spent on bus projects that offer limited long-term impact, suggesting misplaced priorities and a tendency to favor headline projects with higher kickback potential over genuine urban redevelopment.