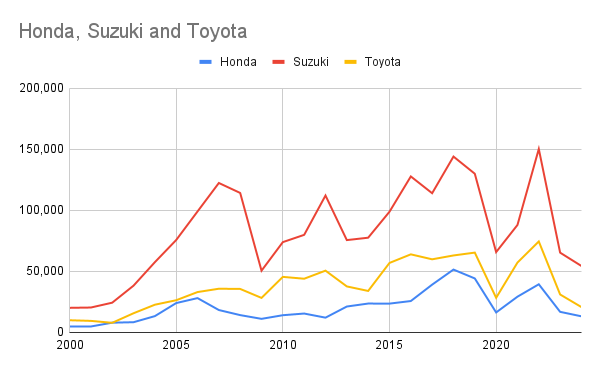

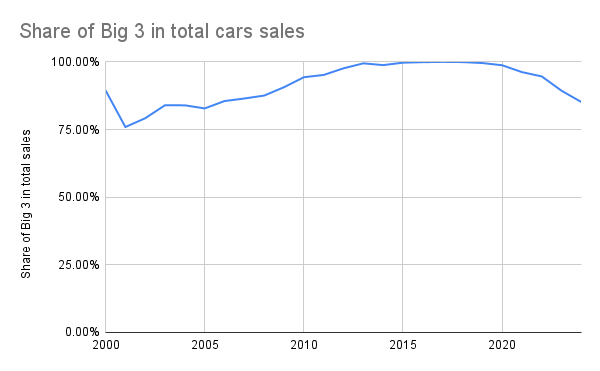

For all the talk of “elite capture” and “rent seeking” in Pakistan, the country has been watching an oligopoly slowly break down over the past five years. For almost every single year since fiscal year 2019, the Big Three automobile assemblers in Pakistan – Toyota, Suzuki, and Honda – have been losing market share in the cars and sports utility vehicles (SUV) segment of the market.

This is a story of incumbents that rested on their laurels, failed to take the threat of competition seriously, and took the customer for granted, not catering to changing preferences and instead adopting the attitude: “you will buy what we produce, on terms that we dictate, on timelines that we please, and you will dare not complain.”

Well, the customer noticed, and when the government decided to finally incentivize newer players to enter the market, the consumer has flocked to them in droves.

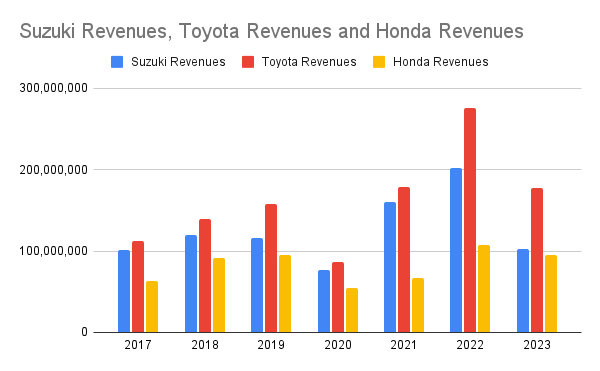

For the fiscal year ending June 30, 2024, the Big Three have sold 85,681 cars and SUVs combined, a number lower than their total sales during fiscal year 2009, according to data from the Pakistan Automotive Manufacturers Association and Lucky Motor Corporation (the only major car company in Pakistan not to be a member of PAMA, and hence reporting its data separately). To be clear, the entire automotive industry has seen volumes collapse by 60.3% since the peak achieved during fiscal year 2022, a change driven entirely by the combined effects of skyrocketing inflation and high interest rates causing a sharp decline in auto lending by the banks.

But the Big Three have been even more badly affected. The industry may be down 60% off its peak volumes, but the Big Three saw their volumes decline by nearly 66% over the past two years. Their market share has also been taking a hit. From a near total dominance of the car and SUV market in 2018, their collective share – in terms of number of vehicles sold – is now down to just over 76% during fiscal 2024.

So how has this been happening? And what comes next? The story starts with hubris born of decades-long unchallenged dominance, protected by government policy.

Cars in Pakistan – a brief history

The region that now constitutes Pakistan was one of the least industrialised parts of pre-Partition India. As a result, at the time of independence, there was absolutely no vehicle assembling capacity in the country. That changed shortly afterwards. In 1949, while India was experimenting with Nehruvian socialism, Pakistan had taken a decidedly capitalist approach to organizing its economy and thus was able to attract General Motors that year.

GM began to assemble Bedford trucks and Vauxhaul cars (a British brand of cars they had bought in 1925). Soon, Pakistani companies began partnering with other American companies to begin assembling other American brands in the country. In 1955, Ford partnered with Ali Automobiles to assemble its cars in Pakistan, Chrysler partnered with Haroon Industries in 1956, and American Motors partnered with Kandawalla Industries in 1962.

These companies never actually manufactured any parts in the country. They were simply assemblers of products manufactured in the United States, or in US-owned plants in Europe. During this period, car ownership was understandably rare, but the few cars that were owned by Pakistanis tended to be American. (There were, of course, the odd old-school elitists who reminisced about the British era and so kept their loyalty to Rolls Royce. But they were a distinct, if filthy stinking rich, minority.)

That American flavor to Pakistani cars came crashing down in 1972, when the left-leaning Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto decided to nationalize all large industrial units in the country. All of the assemblers were consolidated into one organisation, the Pakistan Automotive Cooperate, or PACO, as socialist a name as it gets.

The results of this nationalization were predictable, to say the least. Production and quality cratered, and the up and coming Pakistani middle class relied even more heavily on imported cars to fulfil their needs than ever before. The government was able to achieve somewhat greater localization of the components of the cars, but remained far short of its 75% target. And what localization did happen significantly diminished the quality. It was, after all, a government-controlled company, which meant that supply contracts were available to those with the political connections to go after them, quality be damned.

In 1980, the government decided to start a partial privatization of PACO. Suzuki was the first company to jump into this market, leading to the creation of Pak Suzuki Motor Company, which initially had just a 12.5% stake from Suzuki, with the rest owned by the government. The company started off with the capacity to manufacture 45,000 cars a year by taking some of the plants owned by PACO. By 1990, PSMC built a new plant at Port Qasim, an industrial suburb of Karachi, which took production capacity up to 50,000 cars a year.

In 1992, the government decided to allow private sector companies to outright own auto companies in the country, and placed minimal localization requirements on them. As a result, Suzuki bought out a majority of PSMC, taking its eventual share up to 74%, which is where it stands today. That same year, Honda extended its partnership with Atlas Group, which had been its partner in motorcycles since 1962, to passenger cars and created Honda Atlas Cars.

And in 1993, Toyota partnered with the Habib family to create Indus Motor Company.

There were a cast of other companies that came and went. Ghandhara Industries partnered with Isuzu to make trucks, and with Nissan to make cars. Dewan Farooque Motors worked with Hyundai and Kia to make hatchbacks and sedans. None of them ended up mattering, at least through the late 2010s.

From the early 1990s, the Big Three – as they soon became – came to a tacit agreement. Suzuki kept its monopoly on the hatchback category and Honda and Toyota slugged it out for the sedans. If any new entrants came onto the market (and many tried), they were quickly sullied and sent packing.

In this way, for nearly three decades there were essentially only six options for locally assembled ‘family cars’ in Pakistan. Suzuki at any given time was assembling three to four hatchbacks, with mainstays including the Mehran, the Alto, and the Cultus. Meanwhile Honda produced its cheaper sedan the Honda City, and it’s more expensive competitor to the Toyota Corolla the Honda Civic. Toyota focused on making just one car, albeit in different variants with different engine sizes.

Car production and domestic sales kept limping along at levels below 50,000 vehicles sold in the entire country per year until about the mid-2000s, when the Musharraf Administration’s privatization of banks resulting in the rapid expansion of consumer credit, and car loans became available en masse for the first time in Pakistani history. Car sales took off from under 70,000 in 2003 to nearly 185,000 in 2007, an astonishing pace of growth.

The 2008 financial crisis brought that lending to a halt, and with it came crashing down car sales to a mere 85,000 units in fiscal 2009. Sales slowly crawled back up as both the economy and lending recovered, but were then supercharged during the latter half of the Imran Khan Administration, which encouraged the central bank to loosen regulatory requirements for auto lending, which led to a record-breaking pace of sales. The total number of cars and SUVs sold in Pakistan almost hit 284,000 in fiscal 2022.

The breaking of the oligopoly

By 2022, however, the dominance of the Big Three was already breaking. In 2016, the Nawaz Administration overcame staunch opposition by the Big Three to launch a new automotive policy designed to offer incentives to new manufacturers in the country and introduce both more consumer choice and more competition.

Then came Lucky Group with Lucky Motor Corporation, which launched an assembly partnership with Kia, introducing new lines of small and mid-sized SUVs into the country. The Nishat Group partnered with Hyundai and did the same. This came at a time when globally, Kia and Hyundai have been taking market share from the major American and Japanese automakers even in developed markets.

Then in 2018, Sazgar Engineering, previously only known as an assembler of rickshaws, announced a partnership with Chinese car manufacturer Great Wall Motors, maker of the Haval brand of vehicles, launching its first locally assembled cars in fiscal year 2023.

But it was not just the competition that hit these companies. From late 2021, inflation started to skyrocket as the Imran Khan Administration printed money and subsidized fuel consumption in a bid to stay in power amidst political protests by the opposition. In a bid to control the outflow of foreign exchange, the government in 2021 started placing restrictions on the import of automotive components, meaning that the local assemblers could not import parts from other countries in order to assemble in Pakistan.

With both demand being low and supply being restricted, companies chose to shut down as there were few signs that the situation was going to improve.

Only in the last year, the three companies have seen plant closures with Honda closing the plant for 17 days, Pak Suzuki closing for 55 days Indus Motors closing its plant for a whopping 90 days. That means Indus Motors closed its plant for a quarter of the time in the last year.

And then came the hybrid boom.

The demand for hybrids and SUVs

One more nail in the coffin seems to be the incentives given in the latest federal budget: concessionary sales tax rates were announced for hybrids while advanced income tax was increased on locally assembled cars, increasing their prices.

While this is not designed to weaken the power of the Big Three, it had that effect nonetheless. Among them, only Toyota assembles a hybrid vehicle in Pakistan. The lower sales tax – and rising fuel prices – were a killer combination of incentives for manufacturers of hybrid and electric vehicles, which in Pakistan do not include Honda and Suzuki, and even Toyota has very limited offerings in this segment.

Then there is the fact that a larger and larger proportion of the Pakistani upper middle class is not satisfied with sedans and wants affordable SUVs. The only one among the Big Three that even offers a locally assembled SUV is Toyota, with the Fortuner.

Kia and Hyundai launched in Pakistan with a small and mid-sized SUV focused strategy and began to eat into the market particularly for the more expensive end of sedans, such as the Toyota Corolla and the Honda Civic.

And then the Chinese companies came in with their cars that are both cheaper, and also offer what the consumer wants: hybrid SUVs.

Sazgar and Haval

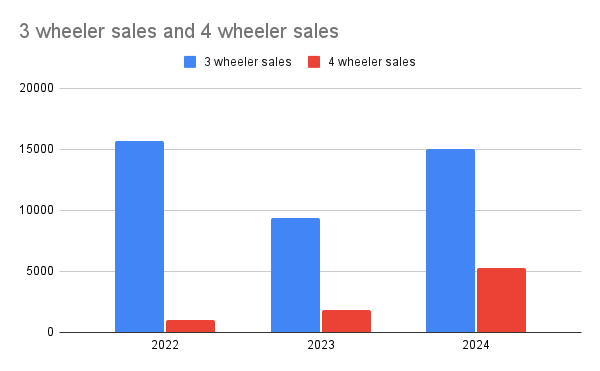

One of the biggest success stories of the past two years is the sales of H6 and Jolion branded cars being sold by Sazgar Engineering. These cars are originally manufactured by Great Wall Motors in China and they are being assembled in the country by Sazgar Engineering. In a period when sales of many of the assemblers have shrunk from last year, Haval has seen its sales actually grow by more than 3 times in the same period. The company saw sales of 1,657 units in 2023 which jumped to 5,319 in 2024.

This success story has not gone unnoticed by investors. The share price of the company was languishing at Rs50 as recently as June 27, 2023. It nearly touched the Rs1,200 per share mark in a span of one year. This was a gain of 2,400% on an investment made last year. To put it in context, the stock market itself has only increased by 100% in the same period. So what is Sazgar Engineering and what is their secret sauce?

Sazgar is a company that has been in the market since the 1990s. A few years ago, the company name was synonymous with green coloured three-wheeled rickshaws buzzing around the country. The company established its first plant for manufacturing of three-wheeler vehicles at Raiwand Road and recently set up its car plant near Sundar, both industrial estates near Lahore, as well.

After the auto policy 2016-21 was announced, the company ventured into the four wheel market with the introduction of Haval brand in the country. The company has also entered the Hybrid Electric Vehicle market now by launching the Haval-HEV which will be locally produced/assembled.

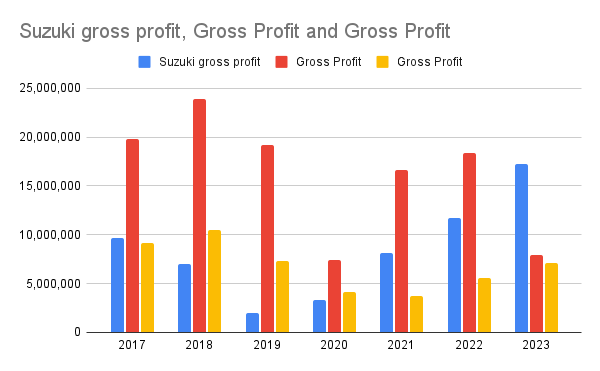

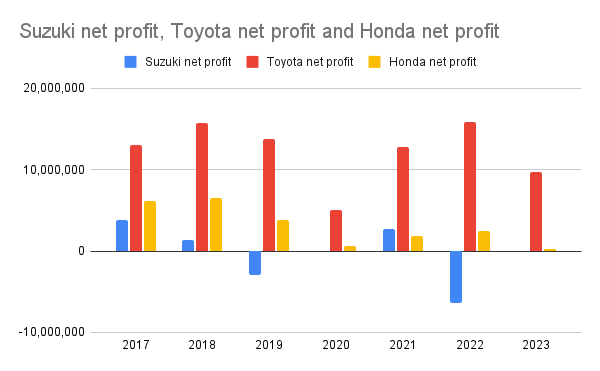

How has the company performed in recent times? Both revenue and profits have been going up dramatically.

During the nine months of the fiscal year ending June 30, 2024 – the latest period for which financials are available – the company recorded revenue of Rs35 billion, compared to just Rs18 billion in the same period last year. The company has actually increased its gross profits from Rs 2.5 billion to Rs 9 billion and its gross margin has increased to 26% for the year. The company also saw its operating profit go to Rs 7 billion from Rs 1.5 billion in the whole of last year. The company has also improved its operating profit margin from 8% to 21% while the company was able to retain Rs 4.4 billion in net profits compared to Rs 0.9 billion in 2023. This meant that its net margin also more than doubled from 5.5% to 12.9%.

A caveat that needs to be attached here is that these 9 month sales figures represent sales of 10,000 units of rickshaws and 3,172 units of cars. The actual figures at June end for rickshaws came to around 15,014 and for cars it came to 5,319. Based on the upward trajectory, it can only be expected that these numbers will improve further. This would mean that a company which had an earning per share of 1.95 per share in 2022 will see an earning per share of more than Rs 73.59 which was recorded for the 9 months period ending in March 2024.

In order to show just how important car sales were for the company, out of total sales of Rs35 billion, cars made up Rs 30 billion in terms of revenue for the company. In terms of operating profits, the company earned Rs 7.5 billion from the cars segment out of Rs 7.6 billion for the company combined.

“Alhamdulillah it has been a great run so far and a divine hand was surely at play for the success we have received. There is a growing shift in the consumer base for New Energy Vehicles and being the first mover in this new segment was a big advantage for us. We currently have the biggest NEV lineup to choose from in Pakistan – Jolion HEV, H6 HEV, Ora 03 BEV, Tank 500 HEV.” states Ammar Hameed, Director Marketing at Sazgar, commenting on the performance of the company and its share price.

The latest annual accounts available for the company are till June 2023 which means that these accounts reflect the sales that were seen by the company for that period which were around 1,657. The company will release its annual accounts for the most recent year in a few months which will show the profitability of the company when it sold a record 5,319 units in 2024.

Over the past year, there have been developments which have helped the company grow further. The Punjab government recently started licensing electric rickshaws which has seen an increase in sales. In addition to that, the company has invested in a 130 Kanal facility in order to expand its car plant further seeing the increasing demand for its products. The company has also gotten its cars ISO certified and its credit rating has been upgraded to A for long term and A-2 for short term. The company has also introduced the ORA and tank-500 which further enhances the product portfolio it provides. Lastly, the company has also started booking for Haval Jolion HEV which has seen people book them in large quantities.

Pivot or Perish

Based on these matters, there can be a few conclusions that can be drawn. First of all, after the implementation of the auto policy, new car companies have entered the market which has broken the monopoly seen by the Big 3 in the past. Consumers feel that they can get a better product at a better price and they need to be wooed in order to be attracted to the old options they were given before. Based on the price point of many of the Big 3, it seems they have little to offer in return. In addition to that, it seems consumers are moving towards bigger SUVs which offer something in addition to the variety that they previously had. There is a significant shift towards people moving from buying Corollas and Civics to buying Tuscons, Sportage and Haval branded cars which not only offer better value for their money but also adhere to a better quality standard. The fact that there are models of Suzuki Alto that do not have power windows shows that the Big 3 are trying to sail on their name for too long.

Another shift which is being seen in the market is consumers moving towards Hybrid Electric Vehicles. With the cost of fuel reaching sky high levels, there is a demand to cut down on some of this cost by investing in a HEV which does make some economic sense. This move has gotten so much traction that Indus Motors recently introduced its 4th generation Toyota Corolla Cross Hybrid Electric Vehicle which is both a SUV and an HEV.

The example of Sazgar shows that there is a market where consumers are willing to pay top dollar in order to get access to better cars and better technology. The Big 3 seem to have missed a trick by not keeping close tabs to the consumer market and trying to impose their products on a dynamic and changing market. Now it seems they stand at a crossroads going forward into the future.

Suzuki might be the best place in the Big 3 to be able to weather some of the storm going forward. The company made up more than 61% of the total cars sold by the Big 3 and saw a decrease of only 17% in terms of its sales last year. It seems there will always be a market for the company as most of its sales are made up of Alto being sold which is the cheapest car available currently.

As mentioned before, Toyota has tried to react by launching an HEV version of its Corolla Cross which might seem to sustain the company to some extent. The company has also decided to source most of its material locally in order to protect it from shocks that it suffered in the last two years. With imports being restricted, companies had to shut down due to lack of raw material required for their production. With Rs 3 billion being invested, it can be seen that the company is looking to pivot to some extent.

The worst placed company in the face of this is Honda which was only able to sell 13,214 units in the last year. The company has no EV based vehicle that they manufacture and even the SUV they assemble, the BR-V, has seen dismal sales figures in the recent past. At this juncture the Big 3 have a decision to make. Either they pivot and try to hold onto their market share or perish in the situation that exists.