When Temu entered Pakistan in late 2024, it stormed the market with a barrage of digital ads and the same formula that had already disrupted retail worldwide: jaw-droppingly low prices, flashy deals, and a model designed to undercut competitors. Launched in the US in 2022 by Chinese tech company Pinduoduo, the platform quickly rose to global prominence with its slogan “Shop like a billionaire,” stripping away intermediaries and connecting buyers directly to manufacturers to deliver prices that seemed impossible. Following the explosive rise of Temu, Pinduoduo’s ambitious Boston-based (yes, the company is American with roots in China) offshoot shaking up global eCommerce, it is clear that Temu’s success is no accident. Its ability to offer products at astonishingly low prices, sometimes even free, has captivated millions, including consumers in Pakistan, a notoriously price-sensitive market.

Within three years, Temu expanded to more than 40 countries, shaking the dominance of Amazon and other global giants. Its rapid ascent triggered a wave of defensive moves and regulatory alarms. Amazon accelerated price-matching programs, while Walmart and Shein began experimenting with supplier integration models. Regulators in Europe and lawmakers in the United States opened investigations into Temu’s data privacy practices, allegations of forced labour in its supply chains, and its ability to skirt fair taxation rules. Consumer advocates also raised concerns about product safety and misleading pricing. Yet despite mounting scrutiny worldwide, the platform’s irresistible bargains continued to drown out the red flags for millions of shoppers.

In Pakistan, Temu carried over the same playbook. It operates quietly, advertises relentlessly, and reveals little about its business operations, strategies, or long-term plans. The company maintains a low profile, preferring secrecy even as it continues receiving backlash from local sellers, policymakers and consumers.

By mid-2025, however, the early bargains had disappeared. Many products had surged by 200 to 300 percent. Items that once cost only a few hundred rupees were now priced in the thousands, while goods previously available for a few thousand crossed the ten-thousand-rupee mark. The abrupt spike left consumers questioning whether Temu’s promise to let them “shop like a billionaire” was ever sustainable or merely a short-term growth tactic.

This article delves into the logic behind the ultra-low prices offered by Temu, how they were able to deliver products at these prices, aggressive subsidies and a blitz-scale growth strategy deployed in Pakistan, what caused the dramatic mid-year shift, where the platform stands today and what the likely future looks like.

Consumer to manufacturer (C2M) – the root of Temu’s ultra low prices

Temu’s rock-bottom pricing in Pakistan was not accidental but built on the same model that they deploy in other countries. Their parent company Pinduoduo pioneered a consumer-to-manufacturer (C2M) approach that bypassed traditional intermediaries. Instead of merely acting as a marketplace, it aggregated consumer demand and directed it straight to manufacturers, allowing products to be custom-made in precise quantities. By guaranteeing high demand, Pinduoduo and Temu could negotiate prices lower than competitors.

However, this would still not be enough to justify the rock bottom prices, because layered on top of this structural advantage is a well-known market entry strategy: burning cash to gain traction. “Low prices and discounts are used to gain market power. Globally, this model is used. Cash is burned when companies enter a market. They use this strategy to attract customers by offering products at very low prices, sometimes even free or at a nominal charge, to acquire market share,” explains Umair Arshad, founding member of the Pakistan eCommerce Association. He likens it to Careem’s early days, when drivers were given generous bonuses to flood the market before the incentives were later reduced. In the same way, Temu’s aggressive discounts and subsidies in Pakistan were never meant as a permanent promise but as a calculated tactic to capture customers quickly and establish dominance.

The C2M model also slashes traditional supply chain inefficiencies, gives more power to small manufacturers and helps meet consumer preferences and demand with greater accuracy. The C2M model also gives Temu the ability to eliminate middlemen like distributors and wholesalers, and eliminate their margins from the cost, resulting in a further reduction in prices.

To elaborate on this, say a local eCommerce seller will rely on importers who will import raw material, then wholesalers and distributors, each adding margin and cost that seller will pass on to the customer. The price for this seller’s customer would be higher because of the addition of successive margins of various intermediaries in the supply chain. Under the C2M model of Temu, these intermediaries are eliminated, allowing Temu to keep the price low. How low? Only Temu knows but we perceive that their ability to aggregate consumer demand resulting in securing low purchase price from manufacturers and elimination of intermediaries is what actually makes their model considerably low-cost, possibly sustainable as long as the demand is high.

Logistics at scale

Price advantages alone cannot explain Temu’s rapid penetration. The company’s logistical prowess is equally critical. Umair Munir, former head of OLX Mall, explains that their home country’s state-subsidised postal system and public sector support create a unique cost structure which allows platforms like Temu to leverage these low rates to ship goods globally at a fraction of what local carriers charge. “For instance, a “free delivery” offer in Pakistan may include international air freight bundled into a consolidated shipment. This reduces the shipment cost per parcel,” he says.

Temu’s logistics network consolidates thousands of small orders into bulk shipments at centralised Chinese hubs (now expanded into other regions). These shipments travel via containerised air cargo, destined for regional clusters like Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad, before last-mile delivery.

Notably, Temu operates its own cargo aircraft servicing routes between Hong Kong, Riyadh, and Karachi, optimising volume and reducing costs further. Such scale-dependent logistics capabilities are unmatchable by smaller local players, who struggle with fragmented, less efficient supply chains.

Uneven competition and CCP complaints

A local eCommerce seller in Pakistan must deal with importers, wholesalers, and distributors, each adding margins that inflate the final price for customers. Temu’s consumer-to-manufacturer model removes these intermediaries and secures ultra-low prices by pooling demand and forcing manufacturers to sell at scale. How low those prices can go is something only Temu knows. But its ability to squeeze manufacturers and cut out middlemen explains why its entry-level prices appear unbeatable, at least while demand remains high.

This advantage is reinforced by Temu’s integration with Pinduoduo’s vast supply chain of more than 11 million manufacturers. Under its fully managed model, sellers have little say beyond producing the goods. Pricing, marketing, logistics, and even customer service are controlled directly by Temu. Sellers may quote a price, but Temu decides whether to accept it and can list the product at that price or lower it to fit its strategy.

For Pakistani sellers, this created an uneven playing field. Organized local platforms operate within transparent supply chains and regulatory costs, while Temu sets the terms unilaterally and faces limited scrutiny.

International reports from Wired and discussions on Reddit show how Temu pressures sellers into cutting margins, often overriding their prices outright. Extending such practices to Pakistan raised a difficult question: are Temu’s low prices the result of innovation, or the exploitation of suppliers combined with regulatory blind spots? Another important factor is that Temu’s price advantage exists only because it relies on its own overseas pool of manufacturers. It cannot realistically open its platform to local Pakistani sellers, even those producing domestically, because their prices reflect the taxes and costs of operating within the formal economy. Temu’s algorithm requires the lowest possible pricing, which local producers cannot sustain once taxes, duties on raw materials, compliance costs, and workforce expenses are included. Hence, their advantage is not efficiency but rather a structural disadvantage, where businesses operating legally are forced to compete against a model that sidesteps the obligations they bear. With e-commerce penetration in Pakistan still below 3%, Temu is not expanding the market; instead, it is cannibalizing it. The platform is diverting share away from local sellers rather than creating new demand.

These concerns soon escalated into formal complaints. Local eCommerce associations and retailers lodged petitions with the Competition Commission of Pakistan (CCP), accusing Temu of predatory practices, bypassing customs, and deliberately undercutting businesses that had to comply with duties and taxes. A key issue highlighted in various complaints by independent sellers, Chainstore Association of Pakistan and Pakistan Retail Business Council is Temu’s pricing strategy, which they describe as predatory. By offering goods at prices significantly lower than those of domestic competitors, Temu is allegedly distorting market competition and threatening the viability of small local businesses. After conducting its own due diligence, the CCP concluded that Temu’s tactics were anti-competitive and wrote to the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA), recommending that Temu be banned in the country as per documents reviewed by Profit.

The growth and marketing blitz

The supply side strategy of Temy works only when the demand is massive. The more customers buying a product at the same time, the more leverage Temu has to pressure manufacturers into offering bulk discounts. To generate that demand, it relies on blitzscaling and blitzmarketing, a playbook that prioritizes speed over efficiency by burning cash to acquire users.

Wired estimates Temu loses about $30 on each order, with overall losses between half a billion and a billion dollars. These losses are deliberate subsidies meant to lure customers away from established global platforms like Amazon, or in Pakistan’s case – local sellers and businesses, who cannot afford to match such tactics.

To make its presence unavoidable, Temu invests heavily in advertising. Globally, it spent an estimated $2 billion on Meta ads in 2024, and Google ranked it the fifth largest advertiser that year. The same approach was visible in Pakistan, where digital platforms were saturated with Temu ads promising products at prices no domestic seller could hope to match.

This completes the demand side of the loop. By spending enormous amounts of money on marketing and user acquisition through discounts, Temu gets a very high customer volume from the very beginning that can justify getting low prices from manufacturers.

By mid-2024, Temu had expanded into more than 40 countries and claimed 150 million users worldwide. In Pakistan, this growth unfolded in a regulatory vacuum, with loopholes in taxation, customs and consumer protection allowing Temu to scale rapidly.

Temu’s method to this madness is simple: opening multiple markets at the same time very quickly further creates the demand to secure lower prices. This creates a very powerful feedback loop: the surge in demand gives Temu more leverage with manufacturers to secure lower prices. The lower prices in turn attract more customers further boosting demand. The cycle continues, allowing Temu to scale rapidly while maintaining its core value proposition of ultra-low prices.

Again, all of this only works if Temu burns a lot of cash from its own pocket to drive massive initial engagement from customers and reach economies of scale. Then to maintain continued economies of scale, it needs to keep discounting which means it would need to continue spending cash on, booking heavily and seriously undercutting competitors to gain market share quickly. Any dip that disrupts its economies of scale would mean higher cash burn on discounts as well an increased spend on marketing to acquire customers again. When it successfully eliminates local competition, that would be its time to make profits from markets that it dominates, resulting in price increase and low or no discounts.

Too small for the government to regulate

Temu’s growth machine was never built to withstand external shocks. Its entire model hinged on exploiting loopholes in global trade rules such as the de minimis exemption, which allows low-value goods to enter countries without duties or heavy scrutiny. In practice, this meant Temu could flood markets with cheap parcels while local businesses importing in bulk faced high customs duties and regulatory costs. Another point to factor in is that they do not have local presence or investment in developing their on-ground infrastructure, which means their cost of doing business is significantly lower than even a small business that would need to hire at least 2-3 people and grow as they expand.

The United States became the first major battleground. Under US law, imports below 800 dollars entered duty-free, a threshold Temu exploited by shipping millions of small parcels under customer names instead of bulk containers. As Temu’s ultra-cheap model gained traction, it was American retailers like GAP, Amazon and Forever 21 that raised the alarm, arguing that Temu’s tactics were not fair competition. That pressure triggered a regulatory crackdown. By April 2025, Washington imposed tariffs of 120 to 145 percent on Chinese imports, effectively ending Temu’s free ride. Temu’s response was telling: it added “import charges” of up to 150 percent at checkout, pulled direct shipments from China, and rushed to build a local fulfillment model.

Other countries moved even faster. Indonesia, Vietnam and Uzbekistan prioritised defending their local industries and tightened rules early, preventing Temu from dumping goods at unsustainable prices. Pakistan, however, lagged behind. Local retailers repeatedly complained to the CCP that Temu was capturing market share unfairly by exploiting It was only on July 1, 2025, after months of industry pressure, that authorities finally reduced the exemption to Rs1,000. The timing told its own story. July 1 was also when Temu’s prices in Pakistan spiked by 200 to 300 percent. Products once priced at a few hundred rupees suddenly cost thousands.

Taxes don’t explain the whole story, demand destruction does

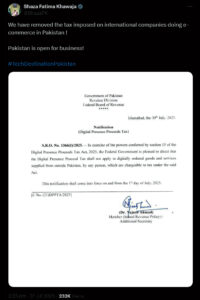

Shopping on Temu once felt like stumbling into a digital thrift store where everything was suspiciously cheap. Hyundai headphones sold for under Rs3,000, magnetic nose strips for less than Rs1,000, prices that seemed too good to be true. They were. Today, the same headphones cost Rs10,319 and nose strips have doubled in price. Even low-duty products like phone covers have become more expensive. What added to the uncertainty was Pakistan’s decision to roll back the 5 percent digital proceeds tax, a move made after a request from the US government. For a brief period, consumers expected this to translate into lower prices on Temu. However, within days it became evident that the rollback had no impact, and prices remained unchanged.

Asfandyar Farrukh, the president of Chainstores Association of Pakistan, explains that customs enforcement in terms of assessing fair value of a product has also gotten stricter.

He explains that when a parcel comes to customs officials in Pakistan, it would be up to officials to assess what fair value of products in a parcel would be and calculate duties based on the fair value calculated by Pakistan Customs. Say a Temu order reaches Pakistan Customs and includes the Rs2,660 Hyundai Earbuds. To assess their fair value, Pakistan Customs can check other online platforms. Online sources list the same earbuds to be at around Rs11,000. The customs officials would charge duty on the parcel at Rs11,000 instead of Temu’s discounted price of Rs2,660. Since the value of the Temu parcel is above Rs1,000, duty would be applicable here, charged at 20 percent of the fair value. This should translate to a Rs2,200 addition in the price of headphones by Temu due to reduction in de minimis exemption limit and stricter customs enforcement while assessing fair value of the product.

The present price of Rs10,319 is not justified by the exemption change and stricter enforcement alone. Moreover, an 18 percent GST is charged by Pakistan Customs which is absorbed by Temu and not passed on to customers. Even if it was passed on, it would not explain a 300 percent increase in headphone prices. Industry insiders suggest Temu was not only exploiting the de minimis loophole but also blatantly bypassing customs rules by under-declaring parcel values. With tighter enforcement, that advantage collapsed overnight.

The bigger issue is structural. Temu’s model depends entirely on high demand to negotiate ultra-low bulk prices from manufacturers. When exemptions were reduced and duties imposed, the economics of its model broke down. Higher prices triggered demand destruction, which meant Temu could no longer guarantee the volumes needed for deep discounts. Pinduoduo itself admitted in its latest financial results that their current profit levels are not sustainable and expect fluctuations in future profitability. Temu and its sellers had faced a reduction in demand due to tariffs and the end of the de minimis exemption in the US, which accounts for a third of its global sales. If demand shrinks in one of its largest markets, the pressure extends globally, including Pakistan.

Temu’s promise of “shop like a billionaire” was never built on loyalty or quality. Its customer base grew on the back of impossibly low prices, with many tolerating subpar goods only because they were cheap. Once those prices began to rise, little remained to differentiate the platform. The company’s refusal to engage with media inquiries, including those from Profit, highlights a troubling lack of transparency. That opacity appears to extend beyond its business practices. Several local influencers who shared negative experiences with Temu reported receiving strikes on social media platforms such as Instagram, raising concerns about how criticism of the company is suppressed.

For Pakistan, the way this situation is handled will be a defining test. Policymakers are often eager to welcome international platforms in the hope of attracting foreign investment, yet Temu has offered little value to the domestic economy. Instead, it has thrived by exploiting loopholes, undercutting compliant businesses, and draining revenue that should have strengthened the local industry. Encouragingly, Pakistan is beginning to respond in line with mature global markets. The Competition Commission of Pakistan has gone beyond warnings and formally recommended that the PTA block Temu, echoing actions already taken in the United States, Indonesia and Vietnam. Such steps are especially significant in an industry like e-commerce, which is still nascent but rapidly emerging as an alternative source of income for hundreds of thousands of local sellers and small businesses. Whether regulators follow through will decide if this ecosystem is protected or left vulnerable to foreign platforms built on subsidies.

But temu now a days not given a exclusive discounts and price are now increase.